Abstract

Vacuum-assisted closure has earned its indications in coloproctology. It has been described with variable results in the treatment of large perineal defects after abdominoperineal excision, in the treatment of stoma dehiscence and perirectal abscesses. The most promising indication for vacuum-assisted closure is probably the treatment of para-anastomotic presacral abscesses following anastomotic leakage after total mesorectal excision. Early initiation of vacuum-assisted closure has the potential to prevent debilitating persistent presacral sinuses precluding stoma closure and bad function of the neorectum. Prompt initiation of endosponge treatment is advised after the anastomotic leakage with the purulent cavity is diagnosed. The endosponge is inserted transanally and connected with a low vacuum bottle. With the gradual reduction in the cavity, the endosponge is reduced in size every 3–4 days when the endosponge is exchanged. It takes 3–6 weeks to close the cavity. Future studies should focus on the stoma closure rate and function to assess whether this intensive postoperative treatment of anastomotic leakages is justified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anastomotic leakage is a serious and feared complication following colorectal surgery and is associated with early and long-term morbidity and mortality. Particularly, (low) anterior resections are associated with a high leakage rate ranging up to 24% [1–3]. Nowadays, the current practice is to perform a partial mesorectal excision for proximal rectal tumors with a colorectal anastomosis, and a total mesorectal excision (TME) for mid and distal tumors with a very distal colorectal or even coloanal anastomosis. In restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis, mostly the total mesorectal excision technique is applied followed by an ileal anal pouch procedure. While removing the total mesorectum, a large dead space is created in the pelvis that is generally filled only partially by the neorectum or the pouch. In case of anastomotic leakage, this cavity can result in a presacral or paranastomotic sinus that cannot heal properly because of insufficient drainage via the anastomotic defect. A defunctioning ileostomy whether performed initially or secondary because of clinical significant anastomotic leakage does not prevent this presacral sinus to occur. The cavity probably heals spontaneously when it is small. When it is large, it might become persistent. Under these circumstances, ileostomy closure is delayed or discarded. If stoma closure is attempted in the presence of a persisting sinus, the function of the neorectum or pouch is often compromised [4]. Even cancer has been reported in the chronic para-anastomotic sinus [5].

Little data exist on how many of these anastomotic leakages eventually will result in a chronic presacral sinus. Arumainayagam et al. reported a 5% incidence in a series of patients that had TME. Only in two out of the five persistent sinuses, the ostomy could be closed [5]. Unpublished data from our own institute suggested a 48% closure rate of the persistent sinus after a median time of almost a year.

It is difficult to decide how to treat a presacral para-anastomotic sinus once it has matured. There are several options: a wait and see policy before stoma closure hoping the sinus will close spontaneously; excision of the anastomosis and formation of a new anastomosis; take down of the anastomosis creating a permanent colostomy; lay-open of the sinus into the neorectum; and installation of occlusive agents, such as fibrin glue. Because of the chronic sepsis and fibrotic tissue, all invasive procedures are technically difficult and complicated. The treatment options trying to preserve the neorectum or pouch have a low success rate with unpredictable stoma closure rates and function. Since the chronic sinus is difficult to treat, the key to success is the prevention of this chronic presacral perianastomotic fistula.

Recently, Weidenhagen et al. [6] described the application of local vacuum sponge treatment of locally contained anastomotic leakage after low anterior anastomosis in rectal cancer patients. In a series of 29 patients with anastomotic leakage, closure of the cavity was achieved in 28 patients. The currently available vacuum sponge is the so-called endosponge (B. Braun Medical B.V., Melsungen, Germany). This is an open-pored polyurethane sponge, which is installed transanally after examination and rinsing of the abscess cavity with saline solution using a flexible endoscope of outer diameter up to 12 mm. The length and size of the abscess cavity are estimated, and the size of the sponge is cut accordingly. When the cavity is too large for one sponge, multiple sponges can be placed. After the introduction of the endoscope into the deepest point of the cavity, a plastic tube, positioned over the scope, is advanced into the deepest point of the cavity. After withdrawal of the endoscope, the endosponge is inserted through the lubricated tube by using a pushing probe while retracting the plastic tube. Next, the sponge is connected to a low vacuum suction bottle, creating a constant negative pressure in the sponge. The correct positioning of the sponge is checked with the endoscope. Fixation of the sponge is not necessary, because low-pressure suction fixes the sponge in the abscess cavity. The endosponge is changed every 3–4 days to prevent the tissue from growing into the sponge causing painful sponge exchanges. Saline solution or lidocaine solution is introduced into the sponge just before its removal to facilitate a painless extraction. At each exchange, the size of the sponge is reduced. Endo-vacuum treatment can be performed in an ambulant outpatient fashion. The vacuum that is essential for the adequate drainage of the sponge is maintained because of the seal induced by the anal sphincter. For this reason, the successful treatment of the presacral cavity with the endosponge after abdominoperineal excision is only possible if the entrance to the presacral cavity is narrow enabling to seal this off by for instance stoma paste as described in this issue by de Hondt et al. [7]. Endosponge treatment will not work in large open perineal defects. Under these circumstances, regular VAC® treatment can be attempted, although maintaining vacuum might be troublesome. It might be useful in stoma dehiscence treatment, as recently described by Crick et al. [8]. Moreover, in the present issue, Durai et al. [9] describe an interesting technique as a modification of the regular VAC® in combination with a Redivac systems for the successful treatment of a perirectal abscess following PPH for hemorrhoids, which was possible due to the very short distance of the abscess orifice from the anal verge and in similar cases may represent an opportunity.

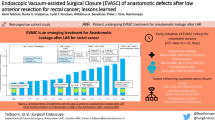

The endo-vacuum facilitates closure of the presacral space by the application of negative pressure into the sponge, ensuring continuous drainage and thereby infection control. It is a misunderstanding that the cavity will be filled with new tissue. Adequate drainage and the vacuum enable the neorectum or pouch to expand and close the cavity. Koperen et al. [10] indicated that the success of endosponge treatment depended on the time when the treatment is started after surgery. In a multicenter study, definitive resolution of the sinus was achieved in 9 out of 16 patients (56%). Closure was achieved in a median of 40 (range 28–90) days with a median amount of 13 sponge replacements (range 8–17). There was closure in six out of eight patients (75%) in the group that started with the endosponge treatment within 6 weeks of surgery compared with 3 out of 8 patients (38%) in the group that started later. In the late treatment group, the scarred and fibrotic neorectum is not able to expand anymore to fill the presacral sinus. The excellent results of Weidenhagen et al. can be explained by the fact that they routinely assessed the anastomoses shortly after surgery, in order to initiate endosponge treatment immediately when anastomotic leakage was observed [6].

Conclusion

The endo-vacuum-assisted closure treatment of the presacral sinus caused by leakage after TME after resection of both benign and malignant pathology is the most promising application of vacuum assisted closure in coloproctology.

Future studies should focus on the stoma closure rate and function to assess whether this intensive postoperative treatment of anastomotic leakages is justified.

References

Ptok H, Marusch F, Meyer F et al (2007) Impact of anastomotic leakage on oncological outcome after rectal cancer resection. Br J Surg 94:1548–1554

Jung SH, Yu CS, Choi PW et al (2008) Risk factors and oncologic impact of anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 51:902–990

Lee WS, Yun SH, Roh YN et al (2008) Risk factors and clinical outcome for anastomotic leakage after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. World J Surg 32:1124–1129

Hallbook O, Sjodahl R (1996) Anastomotic leakage and functional outcome after anterior resection of the rectum. Br J Surg 83:60–62

Arumainayagam N, Chadwick M, Roe A (2009) The fate of anastomotic sinuses after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 11:288–290

Weidenhagen R, Gruetzner KU, Wiecken T, Spelsberg F, Jauch KW (2008) Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a new method. Surg Endosc 22:1818–1825

De Hondt G, Malisse P, Vanden Boer J, Knol J (2009) Chronic pelvic abscedation after completion proctectomy in an irradiated pelvis: another indication for Endo-sponge treatment? Tech Coloproctol 15 [Epub ahead of print]

Crick S, Roy A, Macklin CP (2009) Stoma dehiscence treated successfully with VAC dressing system. Tech Coloproctol 13:181

Durai R, Ng PCH (2009) Perirectal abscess following PPH treatment for haemorrhoids successfully managed with a combination of VAC sponge and Redivac systems: Technical Note. Tech Coloproctol 14 [Epub ahead of print]

van Koperen PJ, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Rosman C et al (2009) The Dutch multicenter experience of the endo-sponge treatment for anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc 23:1379–1383

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bemelman, W.A. Vacuum assisted closure in coloproctology. Tech Coloproctol 13, 261–263 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-009-0543-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-009-0543-x