Abstract

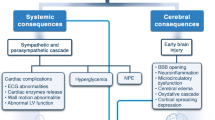

Literature suggest that hypertonic saline (HTS) solution with sodium chloride concentration greater than the physiologic 0.9% can be useful in controlling elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) and as a resuscitative agent in multiple settings including traumatic brain injury (TBI). In this review, we discuss HTS mechanisms of action, adverse effects, and current clinical studies. Studies show that HTS administered during the resuscitation of patients with a TBI improves neurological outcome. HTS also has positive effects on elevated ICP from multiple etiologies, and for shock resuscitation. However, a prospective randomized Australian study using an aggressive resuscitation protocol in trauma patients showed no difference in amount of fluids administered during prehospital resuscitation, and no differences in ICP control or neurological outcome. The role of HTS in prehospital resuscitation is yet to be determined. The most important factor in improving outcomes may be prevention of hypotension and preservation of cerebral blood flow. In regards to control of elevated ICP during the inpatient course, HTS appears safe and effective. Although clinicians currently use HTS with some success, significant questions remain as to the dose and manner of HTS infusion. Direct protocol comparisons should be performed to improve and standardize patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Akdemir G et al (1997) Intraventricular atrial natriuretic peptide for acute intracranial hypertension. Neurol Res 19(5):515–520

Albers GW, Goldberg MP, Choi DW (1992) Do NMDA antagonists prevent neuronal injury? Yes. Arch Neurol 49(4):418–420

Alessandri B et al (1999) Evidence for time-dependent glutamate-mediated glycolysis in head-injured patients: a microdialysis study. Acta Neurochir Suppl 75:25–28

Angle N et al (2000) Hypertonic saline infusion: can it regulate human neutrophil function? Shock 14(5):503–508

Angle N et al (1998) Hypertonic saline resuscitation reduces neutrophil margination by suppressing neutrophil L selectin expression. J Trauma 45(1):7–12, discussion 12–13

Arbabi S et al (1999) Hypertonic saline induces prostacyclin production via extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation. J Surg Res 83(2):141–146

Ayus JC, Krothapalli RK, Arieff AI (1985) Changing concepts in treatment of severe symptomatic hyponatremia. Rapid correction and possible relation to central pontine myelinolysis. Am J Med 78(6 Pt 1):897–902

Battistella FD, Wisner DH (1991) Combined hemorrhagic shock and head injury: effects of hypertonic saline (7.5%) resuscitation. J Trauma 31(2):182–188

Bauer M et al (1993) Comparative effects of crystalloid and small volume hypertonic hyperoncotic fluid resuscitation on hepatic microcirculation after hemorrhagic shock. Circ Shock 40(3):187–193

Berger S, Schwarz M, Huth R (2002) Hypertonic saline solution and decompressive craniectomy for treatment of intracranial hypertension in pediatric severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 53(3):558–563

Boldt J et al (1991) Influence of hypertonic volume replacement on the microcirculation in cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 67(5):595–602

Bourgouin PM et al (1995) Subcortical white matter lesions in osmotic demyelination syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 16(7):1495–1497

Bracken MB et al (1990) A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med 322(20):1405–1411

Bullock R et al (1996) Guidelines for the management of severe head injury. Brain Trauma Foundation. Eur J Emerg Med 3(2):109–127

Chesnut RM (1997) Avoidance of hypotension: conditio sine qua non of successful severe head-injury management. J Trauma 42(5 Suppl):S4–S9

Chesnut RM et al (1993) The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J Trauma 34(2):216–222

Choi DW (1988) Calcium-mediated neurotoxicity: relationship to specific channel types and role in ischemic damage. Trends Neurosci 11(10):465–469

Choi DW (1995) Calcium: still center-stage in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Trends Neurosci 18(2):58–60

Ciesla DJ et al (2001) Hypertonic saline activation of p38 MAPK primes the PMN respiratory burst. Shock 16(4):285–289

Ciesla DJ et al (2001) Hypertonic saline alteration of the PMN cytoskeleton: implications for signal transduction and the cytotoxic response. J Trauma 50(2):206–212

Ciesla DJ et al (2001) Hypertonic saline attenuation of the neutrophil cytotoxic response is reversed upon restoration of normotonicity and reestablished by repeated hypertonic challenge. Surgery 129(5):567–575

Ciesla DJ et al (2000) Hypertonic saline inhibits neutrophil (PMN) priming via attenuation of p38 MAPK signaling. Shock 14(3):265–269, discussion 269–270

Clark BA et al (1991) Atrial natriuretic peptide suppresses osmostimulated vasopressin release in young and elderly humans. Am J Physiol 261(2 Pt 1):E252–E256

Coimbra R et al (1997) Hypertonic saline resuscitation decreases susceptibility to sepsis after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma 42(4):602–606, discussion 606–607

Cooper DJ et al (2004) Prehospital hypertonic saline resuscitation of patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291(11):1350–1357

Cox AT, Ho HS, Gunther RA (1994) High level of arginine vasopressin and 7.5% NaCl/6% dextran-70 solution: cardiovascular and renal effects. Shock 1(5):372–376

Dearden NM et al (1986) Effect of high-dose dexamethasone on outcome from severe head injury. J Neurosurg 64(1):81–88

Dickman CA et al (1991) Continuous regional cerebral blood flow monitoring in acute craniocerebral trauma. Neurosurgery 28(3):467–472

Doyle JA, Davis DP, Hoyt DB (2001) The use of hypertonic saline in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 50(2):367–383

Dubick MA, Wade CE (1994) A review of the efficacy and safety of 7.5% NaCl/6% dextran 70 in experimental animals and in humans. J Trauma 36(3):323–330

Dubick MA et al (1993) Further evaluation of the effects of 7.5% sodium chloride/6% Dextran-70 (HSD) administration on coagulation and platelet aggregation in hemorrhaged and euvolemic swine. Circ Shock 40(3):200–205

Einhaus SL et al (1996) The use of hypertonic saline for the treatment of increased intracranial pressure. J Tenn Med Assoc 89(3):81–82

Fahrner SL et al (2002) Effect of medium tonicity and dextran on neutrophil function in vitro. J Trauma 52(2):285–292

Finberg L (1967) Dangers to infants caused by changes in osmolal concentration. Pediatrics 40(6):1031–1034

Finkelstein E, Corso P, Miller T and associates (2006) The incidence and economic burden of injuries in the United States. Oxford University Press, New York

Fisher B, Thomas D, Peterson B (1992) Hypertonic saline lowers raised intracranial pressure in children after head trauma. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 4(1):4–10

Fishman RA (1975) Brain edema. N Engl J Med 293(14):706–711

Gemma M et al (1996) Hypertonic saline fluid therapy following brain stem trauma. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 8(2):137–141

Gomez CR, Backer RJ, Bucholz RD (1991) Transcranial Doppler ultrasound following closed head injury: vasospasm or vasoparalysis? Surg Neurol 35(1):30–35

Gowrishankar M et al (1997) Profound natriuresis, extracellular fluid volume contraction, and hypernatremia with hypertonic losses following trauma. Geriatr Nephrol Urol 7(2):95–100

Graham DI, Adams JH, Doyle D (1978) Ischaemic brain damage in fatal non-missile head injuries. J Neurol Sci 39(2–3):213–234

Gross D et al (1988) Is hypertonic saline resuscitation safe in ‘uncontrolled’ hemorrhagic shock? J Trauma 28(6):751–756

Gross D et al (1989) Quantitative measurement of bleeding following hypertonic saline therapy in ‘uncontrolled’ hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma 29(1):79–83

Gruber KA (1987) The natriuretic response to hydromineral imbalance. Hypertension 10(5 Pt 2):I48–I51

Gunnar W et al (1988) Head injury and hemorrhagic shock: studies of the blood brain barrier and intracranial pressure after resuscitation with normal saline solution, 3% saline solution, and dextran-40. Surgery 103(4):398–407

Gunnar WP et al (1986) Resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock. Alterations of the intracranial pressure after normal saline, 3% saline and dextran-40. Ann Surg 204(6):686–692

Hariri RJ et al (1989) Human glial cell production of lipoxygenase-generated eicosanoids: a potential role in the pathophysiology of vascular changes following traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 29(9):1203–1210

Hartl R et al (1997) Hypertonic/hyperoncotic saline reliably reduces ICP in severely head-injured patients with intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurochir Suppl 70:126–129

Hartl R et al (1997) Hypertonic/hyperoncotic saline attenuates microcirculatory disturbances after traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 42(5 Suppl):S41–S47

Hess JR et al (1992) The effects of 7.5% NaCl/6% dextran 70 on coagulation and platelet aggregation in humans. J Trauma 32(1):40–44

Hochwald GM et al (1974) The effects of serum osmolarity on cerebrospinal fluid volume flow. Life Sci 15(7):1309–1316

Holcroft JW et al (1987) 3% NaCl and 7.5% NaCl/dextran 70 in the resuscitation of severely injured patients. Ann Surg 206(3):279–288

Holcroft JW et al (1989) Use of a 7.5% NaCl/6% Dextran 70 solution in the resuscitation of injured patients in the emergency room. Prog Clin Biol Res 299:331–338

Huang PP et al (1995) Hypertonic sodium resuscitation is associated with renal failure and death. Ann Surg 221(5):543–554, discussion 554–557

Johnson Jr EM, Deckwerth TL (1993) Molecular mechanisms of developmental neuronal death. Annu Rev Neurosci 16:31–46

Johnson JL et al (1999) Extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 and p38 mitogen- activated protein kinase pathways serve opposite roles in neutrophil cytotoxicity. Arch Surg 134(10):1074–1078

Katzman R et al (1977) Report of Joint Committee for Stroke Resources. IV. Brain edema in stroke. Stroke 8(4):512–540

Kempski O, Behmanesh S (1997) Endothelial cell swelling and brain perfusion. J Trauma 42(5 Suppl):S38–S40

Khanna S et al (2000) Use of hypertonic saline in the treatment of severe refractory posttraumatic intracranial hypertension in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med 28(4):1144–1151

Klatzo I (1967) Presidental address. Neuropathological aspects of brain edema. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 26(1):1–14

Koura SS et al (1998) Relationship between excitatory amino acid release and outcome after severe human head injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl 71:244–246

Kraus GE et al (1991) Cerebrospinal fluid endothelin−1 and endothelin−3 levels in normal and neurosurgical patients: a clinical study and literature review. Surg Neurol 35(1):20–29

Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Thomas KE (2004) Traumatic brain injury in the United States: emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, Atlanta, GA

Lee JH et al (1997) Hemodynamically significant cerebral vasospasm and outcome after head injury: a prospective study. J Neurosurg 87(2):221–233

Lee JM, Zipfel GJ, Choi DW (1999) The changing landscape of ischaemic brain injury mechanisms. Nature 399(6738 Suppl):A7–A14

Legos JJ et al (2001) SB 239063, a novel p38 inhibitor, attenuates early neuronal injury following ischemia. Brain Res 892(1):70–77

Lewis RJ (2004) Prehospital care of the multiply injured patient: the challenge of figuring out what works. JAMA 291(11):1382–1384

Lien YH, Shapiro JI, Chan L (1991)Study of brain electrolytes and organic osmolytes during correction of chronic hyponatremia. Implications for the pathogenesis of central pontine myelinolysis. J Clin Invest 88(1):303–309

Liu, TH et al (1989) Polyethylene glycol-conjugated superoxide dismutase and catalase reduce ischemic brain injury. Am J Physiol 256(2 Pt 2):H589–H593

Marshall LF et al (1998) A multicenter trial on the efficacy of using tirilazad mesylate in cases of head injury. J Neurosurg 89(4):519–525

Martin NA et al (1997) Characterization of cerebral hemodynamic phases following severe head trauma: hypoperfusion, hyperemia, and vasospasm. J Neurosurg 87(1):9–19

Mattox KL et al (1991) Prehospital hypertonic saline/dextran infusion for post- traumatic hypotension. The U.S.A. Multicenter Trial. Ann Surg 213(5):482–491

Moss GS, Gould SA (1988) Plasma expanders. An update. Am J Surg 155(3):425–434

Muizelaar JP et al (1993) Improving the outcome of severe head injury with the oxygen radical scavenger polyethylene glycol-conjugated superoxide dismutase: a phase II trial. J Neurosurg 78(3):375–382

Nicholls D, Attwell D (1990) The release and uptake of excitatory amino acids. Trends Pharmacol Sci 11(11):462–468

Nilsson P et al (1996) Calcium movements in traumatic brain injury: the role of glutamate receptor-operated ion channels. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16(2):262–270

Nonaka M et al (1998) Changes in brain organic osmolytes in experimental cerebral ischemia. J Neurol Sci 157(1):25–30

Oldfield BJ et al (1994) Fos production in retrogradely labelled neurons of the lamina terminalis following intravenous infusion of either hypertonic saline or angiotensin II. Neuroscience 60(1):255–262

Olson JE et al (1997) Blood-brain barrier water permeability and brain osmolyte content during edema development. Acad Emerg Med 4(7):662–673

Onarheim H et al (1990) Effectiveness of hypertonic saline-dextran 70 for initial fluid resuscitation of major burns. J Trauma 30(5):597–603

Partrick DA et al (1998) Hypertonic saline activates lipid-primed human neutrophils for enhanced elastase release. J Trauma 44(4):592–597, discussion 598

Peterson B et al (2000) Prolonged hypernatremia controls elevated intracranial pressure in head-injured pediatric patients. Crit Care Med 28(4):1136–1143

Pfenninger J, Wagner BP (2001) Hypertonic saline in severe pediatric head injury. Crit Care Med 29(7):1489

Poli de Figueiredo LF et al (1995) Hemodynamic improvement in hemorrhagic shock by aortic balloon occlusion and hypertonic saline solutions. Cardiovasc Surg 3(6):679–686

Qureshi AI et al (1998) Use of hypertonic (3%) saline/acetate infusion in the treatment of cerebral edema: effect on intracranial pressure and lateral displacement of the brain. Crit Care Med 26(3):440–446

Qureshi AI et al (1999) Use of hypertonic saline/acetate infusion in treatment of cerebral edema in patients with head trauma: experience at a single center. J Trauma 47(4):659–665

Qureshi AI, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ (1999) Treatment of elevated intracranial pressure in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: comparison between mannitol and hypertonic saline. Neurosurgery 44(5):1055–1063, discussion 1063–1064

Qureshi AI, Suarez JI, Bhardwaj A (1998) Malignant cerebral edema in patients with hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage associated with hypertonic saline infusion: a rebound phenomenon? J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 10(3):188–192

Rabinovici R et al (1992) Hemodynamic, hematologic and eicosanoid mediated mechanisms in 7.5 percent sodium chloride treatment of uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock. Surg Gynecol Obstet 175(4):341–354

Rabinovici R et al (1996) Hypertonic saline treatment of acid aspiration-induced lung injury. J Surg Res 60(1):176–180

Ramires JA et al (1992) Acute hemodynamic effects of hypertonic (7.5%) saline infusion in patients with cardiogenic shock due to right ventricular infarction. Circ Shock 37(3):220–225

Reed RL 2nd et al (1991) Hypertonic saline alters plasma clotting times and platelet aggregation. J Trauma 31(1):8–14

Riddez L et al (1998) Central and regional hemodynamics during uncontrolled bleeding using hypertonic saline dextran for resuscitation. Shock 10(3):176–181

Rizoli SB et al (1999) Hypertonicity prevents lipopolysaccharide-stimulated CD11b/CD18 expression in human neutrophils in vitro: role for p38 inhibition. J Trauma 46(5):794–798, discussion 798–799

Rizoli SB et al (1998) Immunomodulatory effects of hypertonic resuscitation on the development of lung inflammation following hemorrhagic shock. J Immunol 161(11):6288–6296

Sato K et al (1993) Role of vagal nerves and atrial natriuretic hormone in vasopressin release and a diuresis under hypertonic volume expansion. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 129(1):65–74

Schatzmann C et al (1998) Treatment of elevated intracranial pressure by infusions of 10% saline in severely head injured patients. Acta Neurochir Suppl 71:31–33

Schroder ML et al (1998) Early cerebral blood volume after severe traumatic brain injury in patients with early cerebral ischemia. Acta Neurochir Suppl 71:127–130

Schroder ML et al (1998) Regional cerebral blood volume after severe head injury in patients with regional cerebral ischemia. Neurosurgery 42(6):1276–1280, discussion 1280–1281

Schroder ML, Muizelaar JP, Kuta AJ (1994) Documented reversal of global ischemia immediately after removal of an acute subdural hematoma. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg 80(2):324–327

Schwarz S et al (1998) Effects of hypertonic saline hydroxyethyl starch solution and mannitol in patients with increased intracranial pressure after stroke. Stroke 29(8):1550–1555

Shackford SR (1997) Effect of small-volume resuscitation on intracranial pressure and related cerebral variables. J Trauma 42(5 Suppl):S48–S53

Shackford SR, Schmoker JD, Zhuang J (1994) The effect of hypertonic resuscitation on pial arteriolar tone after brain injury and shock. J Trauma 37(6):899–908

Shackford SR, Zhuang J, Schmoker J (1992) Intravenous fluid tonicity: effect on intracranial pressure, cerebral blood flow, and cerebral oxygen delivery in focal brain injury. J Neurosurg 76(1):91–98

Shields CJ et al (2000) Hypertonic saline attenuates end-organ damage in an experimental model of acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 87(10):1336–1340

Simma B et al (1998) A prospective, randomized, and controlled study of fluid management in children with severe head injury: lactated Ringer’s solution versus hypertonic saline. Crit Care Med 26(7):1265–1270

Spiers JP et al (1993) Resuscitation of hemorrhagic shock with hypertonic saline/dextran or lactated Ringer’s supplemented with AICA riboside. Circ Shock 40(1):29–36

Steenbergen JM, Bohlen HG (1993) Sodium hyperosmolarity of intestinal lymph causes arteriolar vasodilation in part mediated by EDRF. Am J Physiol 265(1 Pt 2):H323–H328

Sterns RH, Riggs JE, Schochet SS Jr (1986) Osmotic demyelination syndrome following correction of hyponatremia. N Engl J Med 314(24):1535–1552

Suarez JI et al (1999) Administration of hypertonic (3%) sodium chloride/acetate in hyponatremic patients with symptomatic vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 11(3):178–184

Suarez JI et al (1998) Treatment of refractory intracranial hypertension with 23.4% saline. Crit Care Med 26(6):1118–1122

Thiel M et al (2001) Effects of hypertonic saline on expression of human polymorphonuclear leukocyte adhesion molecules. J Leukoc Biol 70(2):261–273

Tollofsrud S et al (1998) Hypertonic saline and dextran in normovolaemic and hypovolaemic healthy volunteers increases interstitial and intravascular fluid volumes. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 42(2):145–153

Trachtman H (1991) Cell volume regulation: a review of cerebral adaptive mechanisms and implications for clinical treatment of osmolal disturbances. I. Pediatr Nephrol 5(6):743–750

Trachtman H (1992) Cell volume regulation: a review of cerebral adaptive mechanisms and implications for clinical treatment of osmolal disturbances: II. Pediatr Nephrol 6(1):104–112

Trachtman H et al (1993) The role of organic osmolytes in the cerebral cell volume regulatory response to acute and chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 3(12):1913–1919

Unterberg A et al (1993) Long-term observations of intracranial pressure after severe head injury. The phenomenon of secondary rise of intracranial pressure. Neurosurgery 32(1): 17–23, discussion 23–24

Vassar MJ, Perry CA, Holcroft JW (1990) Analysis of potential risks associated with 7.5% sodium chloride resuscitation of traumatic shock. Arch Surg 125(10):1309–1315

Vassar MJ, Perry CA, Holcroft JW (1993) Prehospital resuscitation of hypotensive trauma patients with 7.5% NaCl versus 7.5% NaCl with added dextran: a controlled trial. J Trauma 34(5):622–632, discussion 632–633

Vassar MJ et al (1991) 7.5% sodium chloride/dextran for resuscitation of trauma patients undergoing helicopter transport. Arch Surg 126(9):1065–1072

Vespa P et al (1998) Increase in extracellular glutamate caused by reduced cerebral perfusion pressure and seizures after human traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study. J Neurosurg 89(6):971–982

Wade CE et al (1997) Individual patient cohort analysis of the efficacy of hypertonic saline/dextran in patients with traumatic brain injury and hypotension. J Trauma 42(5 Suppl):S61–S65

Walsh JC, Zhuang J, Shackford SR (1991) A comparison of hypertonic to isotonic fluid in the resuscitation of brain injury and hemorrhagic shock. J Surg Res 50(3):284–292

Worthley LI, Cooper DJ, Jones N (1988) Treatment of resistant intracranial hypertension with hypertonic saline. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg 68(3):478–481

Yamashita T et al (1997) Induction of Na+/myo-inositol co-transporter mRNA after rat cryogenic injury. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 46(1–2):236–242

Junger WG et al (1998) Hypertonicity regulates the function of human neutrophils by modulating chemoattractant receptor signaling and activating mitogen-activated protein kinase p38. J Clin Invest 101(12):2768–2779

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comments

Attila Schwarcz, Pécs, Hungary

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) imposes severe problems in developed countries since it disables a huge number of healthy and young individuals every year. TBI is also one of the leading causes of mortality among young adults. The primary TBI is often complicated with diverse pathological processes that result in increased intracranial pressure (ICP) decreasing cerebral perfusion severely. The management of raised ICP is still an open field for improvements. Tyagi et al. review literature data of a promising alternative aimed at ICP reduction: hypertonic saline solution (HTS). It appears that use of HTS in the prehospital management of patients with TBI does not result in either better neurological outcome or in lower rate of mortality. However, application of HTS in intensive care units causes prompt and significant ICP decrease. It is also suggested that HTS can be effective in cases refractory to standard mannitol therapy. The inverse relationship between ICP and serum Na+ levels is well documented both in animals and humans. The often observed rebound effect after bolus injection of HTS may be prevented by continuous infusion targeted toward a high level of serum Na+.

As it is obvious from the up-to-date review of Tyagi et al., class I evidence (i.e., double blind, prospective, multicenter study) is still missing as concerns application of HTS (e.g., dose, duration of treatment, ideal serum Na+ level, etc.). However, based on the literature data, application of HTS may be recommended to lower ICP in intensive care units not only as an ultimum refugium but also as a regular treatment.

Oliver W. Sakowitz, Andreas W. Unterberg, Heidelberg, Germany

In their review, Tyagi et al. discuss the mechanisms of action, adverse effects, and current clinical studies on the use of hypertonic saline (HTS) in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Osmotherapy with HTS (and in combination with colloids for small-volume resuscitation) is a promising concept which has been investigated experimentally and clinically for the past two decades. However, so far only one large prospective, randomized clinical study has been conducted by Cooper and coworkers [1]. Prehospital treatment of patients with TBI and hypotension with HTS did not influence outcome when compared to conventional fluid therapy.

Clinical experience from neurointensive care, however, is different, and especially for pediatric TBI promising results have been published. It may be argued that outcome parameters, such as Glasgow Outcome Scale scores after 6 or 12 months, may not adequately reflect the clinical value of HTS. Surrogate parameters, such as brain tissue oxygenation, metabolism, and regional cerebral blood flow, more and more commonly used in multimodality monitoring, could be used alternatively to directly assess “tissue outcome” [2, 3].

The authors are to be commended for their thorough literature review and discussion not only limited to TBI, but also stroke and resuscitation medicine. Their approach of a protocol-based comparison is especially helpful to gain an overview of the different hypertonic fluid regimens currently in use. It also shows the difficulty of comparing these heterogeneous treatments with a “conventional” mannitol-based regimen if equiosmolar doses are not strictly used.

More prospective and randomized clinical studies are needed to elucidate the value of hypertonic fluid therapy in the neurointensive care unit.

References

1. Cooper et al. (2004) Prehospital hypertonic saline resuscitation of patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:1350–1357

2. Hartl et al. (1997) Mannitol decreases ICP but does not improve brain-tissue pO2 in severely head-injured patients with intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurochir Suppl 70:40–42

3. Sakowitz et al. (2007) Effects of mannitol bolus administration on intracranial pressure, cerebral extracellular metabolites, and tissue oxygenation in severely head-injured patients. J Trauma 62:292–298

Ignacio J. Previgliano, Buenos Aires, Argentina

This excellent review by Dr. Tyagi and coworkers provides an analysis of the role of hypertonic saline (HTS) in different types of brain injuries. The first conclusion one can make is that there is not sufficient evidence to favor the routine use of HTS either in the prehospital setting or in the emergency room or in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Most of the prospective papers showed no difference between HTS regimens (3% or 7% plus dextran) and conventional resuscitation with lactated Ringer’s solution in the prehospital setting and long-term neurological recovery assessed by the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale, specially the Australian research performed by Cooper et al. and Wade et al.’s meta-analysis that showed that HTS is not different from the standard of care and that HTS plus dextran may be superior.

Prospective randomized trials in the ICU have an insufficient number of patients to achieve either a standard or a guideline in HTS use. There is also a lack of uniformity in dosage and concentration, with a wide range from 3 to 29% and variations in volume from 100 ml/bolus to continuous infusion.

An important issue is the development of osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS), previously known as pontine (PM) or extrapontine myelinolysis (EPM). This syndrome, first described by Adams in chronic alcoholics in 1959, includes tetraplegia, pseudobulbar palsy, and acute changes in mental status leading to coma or death without intervention. Anatomopathological findings of symmetric, demyelinating focus prominent in the central pons were associated with this clinical picture. Similar histologic symmetric lesions were later identified in extrapontine locations, including the white matter of the cerebellum, thalamus, globus pallidus, putamen, and lateral geniculate body, a condition termed EPM. There is an increased risk of PM or EPM development when hyponatremia correction is higher than 2 mmol/h or 8 mmol/day.

Diagnosis is possible by clinical symptoms and by MRI studies (“bat wings” sign in the pons). In the setting of severe brain injury patients, differential diagnosis should be made with primary brain stem lesions, critical care polyneuropathy, or hypoxic anoxic encephalopathy among others.

Only Khanna et al.’s papers addressed the lack of incidence of ODS, but both papers pertain to a pediatric population and one of them is retrospective.

So the risk of ODS is not established and the odds of developing it is high.

The choice of the osmotic agent in our practice is based in the patient’s sodium: if it is normal or high we use mannitol in a 0.5 g/kg per bolus, if it is below 130 mEq/l we use 3% HTS in a 2 ml/kg per bolus. Both boluses are repeated at a 4-h interval according to the intracranial pressure. The other potential use of 3% or 7% HTS in our unit is refractory intracranial hypertension, before using indomethacin, barbiturates, or decompressive craniotomy.

I agree with the author’s statement “it may be that adequate volume and hemodynamic resuscitation is in fact the critical factor in improving neurological outcome.” It could be achieved either with HTS or mannitol under expert intensivist surveillance.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tyagi, R., Donaldson, K., Loftus, C.M. et al. Hypertonic saline: a clinical review. Neurosurg Rev 30, 277–290 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-007-0091-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-007-0091-7