Abstract

Background

Whether submucosal fibrosis is related to ulceration and affects the outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric cancer (EGC) is unknown. This study aimed to determine ESD outcome in relationship to degree of submucosal fibrosis of gastric epithelial neoplasms and to identify factors predictive of submucosal fibrosis.

Methods

Eight hundred ninety-one patients with 1,027 gastric epithelial neoplasms were treated by ESD from April 2005 to January 2011. Complete en bloc resection and perforation rates in relationship to degree of submucosal fibrosis (F0, no fibrosis; F1; mild fibrosis; F2, severe fibrosis) were determined during ESD, as well as degree of concordance between endoscopically observed ulceration and pathologically determined ulceration and pathological fibrosis stained with Masson’s trichrome.

Results

The complete en bloc resection rate was significantly low and the perforation rate was high for F2 versus F0/F1 tumors. Ulceration, tumor size ≥30 mm, and depressed histological type were independent risk factors for severe (F2) fibrosis. No fibrosis (F0) was observed in 77 % (732/951) of endoscopically negative ulceration cases, whereas fibrosis was observed in 100 % (76/76) of endoscopically positive cases. Masson trichrome staining was weak in 97 % (710/732) of F0, moderate in 85 % (181/214) of F1, and strong in 100 % (81/81) of F2 cases.

Conclusions

Histopathological type of submucosal fibrosis predicts outcome of ESD for EGC. Endoscopic indications of F2 submucosal fibrosis are ulceration, tumor ≥30 mm, and macroscopic depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as gastric cancer confined to the mucosa or submucosa (T1 cancer), regardless of whether regional lymph node metastases are present [1]. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has become a standard treatment for EGC [2–11]. ESD involves circumferential mucosal incision and direct submucosal dissection, making it possible to resect en bloc even large tumors with endoscopically clear margins in any part of the stomach. The ESD procedure allows precise histological assessment of the resected specimen and prevents residual disease and local recurrence [2, 12–14]. Despite the success of ESD, incomplete resection has resulted when it has been applied to EGCs with ulceration [2, 12, 15–18]. This difficulty raises the question of whether or to what extent additional clinicopathological factors, such as submucosal fibrosis, affect the outcome of ESD for EGC.

We retrospectively assessed the outcome of ESD for gastric epithelial neoplasm in relationship to the presence or absence of submucosal fibrosis as observed during ESD in a large number (n = 1,077) of patients treated at a single center. In addition, we investigated whether a relationship exists between endoscopically observed submucosal fibrosis, pathologically observed submucosal fibrosis, and ulceration.

Patients and methods

Patients

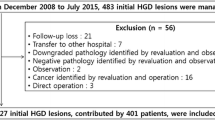

We observed 1,035 consecutive patients with 1,171 gastric epithelial neoplasms who underwent ESD at Hiroshima University Hospital between April 2005 and January 2011. For the purpose of the study, we included cases that met the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2010 [19] for ESD criteria and excluded cases that did not meet these criteria. One hundred forty-four patients were excluded: 117 patients with 117 lesions that did not meet the criteria, 17 with lesions arising in a remnant stomach, 3 given a gastric tube after esophagectomy, and 7 with postendoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)/ESD scar, i.e., 17 in whom prior surgery could have confounded the study results. Thus, this study comprised 891 patients with 1,027 lesions.

All patients provided written informed consent before ESD. The study was carried out with approval from the institutional review board of Hiroshima University.

ESD procedure and assessment of immediate outcome

ESD was performed with a conventional single-channel endoscope (GIF-450RD5; FUJIFILM Medical, Tokyo, Japan; GIF-H260, -H260Z, or -Q260J; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a two-channel endoscope (GIF-450D5; FUJIFILM Medical or 2TQ260M; Olympus). Several spots were marked with a needle knife or argon plasma coagulation 5–10 mm outside the margin of each lesion. After injection of 10 % glycerin solution with 0.0025 % epinephrine and 0.005 % indigo carmine into the submucosa, an initial incision was made outside the marks with a needle knife. An IT knife or IT knife-2 or a HOOK knife, FLEX knife (KD-610L, KD-611L, KD-620LR, KD-630L; Olympus), or FLUSH knife (DK2618JB; FUJIFILM Medical) was then inserted into the initial incision, and electrosurgical current was applied with the use of an electrosurgical generator (VIO300D; Drycut mode, 50 W, effect 4, or Endocut I mode, effect 2; Erbe, Tubingen, Germany; or ESG100, Pulsecut Slow mode, 40 W; Olympus) to complete the circumferential mucosal incision around the lesion. The ESD procedure was performed mainly with the IT knife or IT knife-2. However, if the scope was positioned in front of and against the lesion or if the tumor was ulcerated, the IT knife or IT knife-2 was exchanged for a hook knife, flex knife, or flush knife: these were used to exfoliate submucosal layers. Injection of 10 % glycerin solution with 0.0025 % epinephrine was repeated as needed, and further resection was carried out to ensure total removal of the lesion.

Complete en bloc resection was defined as en bloc resection achieved endoscopically along with histological confirmation of tumor-free margins, i.e., absence of tumor cells in both the vertical and horizontal margins of the specimen. Perforation was diagnosed endoscopically just after resection or by the presence of free air on a plain abdominal radiograph or a computed tomography image.

Classification of submucosal fibrosis during ESD and analysis of related outcome

In all patients, presence or absence of submucosal fibrosis was assessed under white light conventional endoscopy and chromoendoscopy and classified according to the system as we previously reported [20] and based on observations at the time of injection of sodium hyaluronate with indigo carmine (Fig. 1): F0, no fibrosis, which manifests as a blue transparent layer; F1, mild fibrosis, which appears as a white web-like structure in the blue submucosal layer; and F2, severe fibrosis, which appears as a white muscular structure without a blue transparent layer in the submucosal layer. The white muscular structure was similar to the muscular layer; therefore, this structure could not be easily separated from the muscular layer.

Degree of fibrosis of the submucosal layers: F0 no fibrosis, which manifested as a blue transparent layer; F1 mild fibrosis, which appears as a white web-like structure in the blue submucosal layer; and F2 severe fibrosis, which appears as a white muscular structure without a blue transparent layer in the submucosal layer

The complete en bloc resection rate and the perforation rate were determined in relationship to the degree of submucosal fibrosis. These complete en bloc resection rates and perforation rates were further analyzed according to lesion size. Subsequently, clinicopathological factors, i.e., age, sex, lesion location, histological type (intestinal vs. diffuse), tumor size (<30 vs. ≥30 mm), macroscopic type (depressed vs. nondepressed), and ulceration, were examined in relationship to the F0–F1 versus F2 classification.

Endoscopic and pathological identification of ulceration and histological assessment of submucosal fibrosis

The histological sections were examined for ulceration by one pathologist (F.S.) who blinded to all clinical information. Histopathological diagnoses were based on the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma [1]. Endoscopically determined ulceration was defined as clear endoscopic observation of ulcer formation or converging folds without agglutination [10, 21]. Pathologically determined ulceration was defined as disruption of the muscularis mucosa with involvement of the submucosal layers [22, 23]. Consecutive 4-μm-thick sections were cut from each paraffin-embedded sample and immunolabeled. Masson trichrome staining (HT15-1KT; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to evaluate submucosal fibrosis; collagen stains blue [24, 25]. The degree of histological submucosal fibrosis was evaluated as follows (Fig. 2): mild fibrosis, which manifests as weak blue staining of collagen fibers in submucosal layers; moderate fibrosis, which manifests as moderate blue staining of collagen fibers in submucosal layers; and severe fibrosis, which manifests as strong blue staining of collagen fibers in submucosal layers. We investigated the relationship between endoscopic or pathological ulceration and the degree of submucosal fibrosis as well as the relationship between the degree of submucosal fibrosis and the degree of Masson trichrome staining.

Histological assessment of the submucosal layer by Masson trichrome staining: mild fibrosis, weak blue staining of collagen fibers in the submucosal layer; moderate fibrosis, moderate blue staining of collagen fibers in the submucosal layer; severe fibrosis, strong blue staining of collagen fibers in the submucosal layer

Statistical analysis

Complete en bloc resection rates were examined in relationship to degree of fibrosis (F0, F1, or F2) and in relationship to tumor size (<30 or ≥30 mm), perforation rates were examined in relationship to degree of fibrosis and in relationship to tumor size, and differences were analyzed by χ2 test. Clinicopathological factors were examined in relationship to degree of fibrosis; differences were analyzed by Student’s t test or χ2 test, as appropriate. Factors shown to be significant were entered into multivariate analysis to identify those independently predictive of F2 fibrosis. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Outcome of ESD accompanied by fibrosis

Complete en bloc resection rates are shown per tumor size (<30 vs. ≥30 mm) and degree of fibrosis in Table 1. The overall complete en bloc resection rate was 96 % (990/1,027). For tumors <30 mm, the complete en bloc resection rate was 97 % (882/907), and for tumors ≥30 mm, the complete en bloc resection rate was 90 % (108/120). The difference in these complete en bloc resection rates was significant (P < 0.01). In addition, the complete en bloc resection rate was significantly lower for lesions accompanied by F2 fibrosis than for other lesions (F0–F1), regardless of tumor size (77 vs. 96 %).

The overall perforation rate was 3 % (29/1,027). The perforation rate for tumors <30 mm was 3 % (25/907), and the rate for tumors ≥30 mm was 3 % (4/120). The difference in these rates was not significant. However, the overall perforation rate was significantly higher for lesions accompanied by F2 fibrosis than for other lesions (F0–F1). Specifically, the perforation rate for tumors <30 mm with F2 fibrosis was 9 % (5/57), and that for other tumors <30 mm was 2 % (20/850). This difference was significant (P = 0.016), but the fibrosis-related difference (F2 vs. F0–F1) among tumors ≥30 mm was not significant.

Clinicopathological factors in relationship to F2 fibrosis

Fibrosis is shown in relationship to clinicopathological factors in Table 2. Male sex, tumor location in the upper or middle third of the stomach, tumor size ≥30 mm, depressed-type tumor, and endoscopic ulceration were shown to be significant factors. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed endoscopic ulceration (vs. no ulceration, P < 0.001), tumor size ≥30 mm (vs. <30 mm, P < 0.001), and depressed-type tumor (vs. nondepressed-type tumor, P < 0.001) to independent factors predictive of F2 fibrosis (Table 3).

Relationship between endoscopic ulceration and degree of submucosal fibrosis

Pathological ulceration and degree of submucosal fibrosis are shown in relationship to endoscopic ulceration in Table 4. Concordance between absence of endoscopic ulceration and absence of pathological ulceration was 100 % (951/951), and that between presence of endoscopic ulceration and presence of pathological ulceration was 97 % (74/76). No fibrosis was observed in 77 % (732/951) of the endoscopically negative cases, and thus they were categorized as F0 cases, whereas fibrosis was observed in 100 % (76/76) of the endoscopically positive cases.

Relationship between the degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis and degree of Masson trichrome staining

Results of Masson trichrome staining are shown in relationship to degrees of submucosal fibrosis in Table 5. Ninety-seven percent (710/732) of F0 cases showed weak staining, 85 % (181/214) of F1 cases showed moderate staining, and 100 % (81/81) of F2 cases showed strong staining.

Discussion

We reported previously that ulceration or tumor size >21 mm prevented complete removal of EGCs by ESD [15]. Similarly, Oda et al. [16] reported that tumor location in the upper or middle third of the stomach, tumor size >21 mm, and ulceration were each associated with piecemeal resection of ECG, affecting curability by ESD. In addition, Ohnita et al. [17] showed by multivariate analysis that ulceration is a primary cause of incomplete resection of EGC by ESD. Moreover, ulceration significantly increases the time required for the operation and is a risk factor for perforation [16, 26, 27], although it is not a cause of postoperative bleeding [16, 28].

Previously, we classified non-fibrosis/fibrosis observed during submucosal dissection of colorectal tumors as F0, F1, or F2 and investigated treatment results per class. Mixing indigo carmine into injection solution is useful and is indispensable to recognize the degree of endoscopic submucosal fibrosis. The complete en bloc resection rate was significantly lower for F2 lesions than for F0 and F1 lesions, regardless of the treatment period or tumor size [20]. Thus, we learned that severe fibrosis reduces the likelihood of complete en bloc resection by ESD. Submucosal dissection of F2 lesions is difficult because maintaining an appropriate dissection depth requires skill. Overly shallow dissection performed to avoid perforation may cause heat denaturation of the excised specimen, making detailed histopathological examination of the sample difficult and thus hindering clinical judgment [16, 17, 29].

The present study revealed three factors predictive of F2 fibrosis in the submucosa: ulceration, tumor size ≥30 mm, and depressed-type tumor. On finding a lesion with these features, which causes difficulty in continuing the procedure, clinicians may need to consider surgical resection, taking into account the extent and depth of the fibrosis, skill of the operator, and patient background.

According to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2010, differentiated-type intramucosal adenocarcinoma of ≤3 cm falls under the expanded indications for EGC with ulceration [19]. Although it is not specified in the guidelines whether endoscopically determined ulceration or pathologically determined ulceration should be the standard [19], concordance between the two methods of identifying ulceration was 99 % in the present study, which indicates that ulceration can be diagnosed solely on the basis of endoscopic examination. Nevertheless, submucosal fibrosis was observed in 23 % of cases without endoscopic ulceration. Clinically, our endoscopic classification of submucosal fibrosis is useful. For example, the lesion larger than 30 mm in diameter with F2 during ESD is easily recognized as it does not meet the ESD criteria according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2010 [19], because F2 directly indicates pathological severe fibrosis.

Studies are needed to refine techniques for identifying the lesions that have submucosal fibrosis without endoscopic ulceration before ESD. Even though endoscopic ultrasonography is useful for predicting ulceration [30], accurate assessment of invasion depth is difficult in cases of ulceration [31]. Further studies are needed to evaluate the usefulness of EUS for diagnosing fibrosis. Thus far, we have reported that submucosal invasion of ≤1,000 μm, tumor diameter ≤30 mm, differentiated type as the dominant histological type, and absence of vessel involvement may allow expansion of the criteria for determining whether endoscopic resection can be considered curative for submucosal invasive gastric cancer [32, 33]. New methods for recognizing ulceration and submucosal cancers preoperatively will be important.

Finally, we evaluated submucosal fibrosis of gastric epithelial neoplasms by means of Masson trichrome staining during ESD and found that endoscopic classification as F0 (no fibrosis), F1 (moderate fibrosis), or F2 (severe fibrosis) directly reflects the histopathological type of submucosal fibrosis and is thus predictive of ESD outcome; therefore, classification of fibrosis during ESD is clinically useful. Further improvement and development of endoscopic devices and peripherals are needed before ESD can be relied upon for safe and complete treatment of lesions with severe fibrosis, especially large lesions.

References

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–12.

Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, Mouri R, Hirata M, Kawamura T, et al. Advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:877–83.

Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, Iishi H, Tanabe S, Oyama T, et al. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262–70.

Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225–9.

Imagawa A, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Kato J, Kawamoto H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: results and degrees of technical difficulty as well as success. Endoscopy. 2006;38:987–90.

Eguchi T, Gotoda T, Oda I, Hamanaka H, Hasuike N, Saito D, et al. Is endoscopic one-piece mucosal resection essential for early gastric cancer? Dig Endosc. 2003;15:113–6.

Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, Sasaki A, Nakazawa K, Miyata T, et al. Successful en bloc resection of large superficial tumors in the stomach and colon using sodium hyaluronate and small-caliber-tip transparent hood. Endoscopy. 2003;35:690–4.

Oyama T, Kikuchi Y. Aggressive endoscopic mucosal resection in the upper GI tract: hook knife EMR method. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2002;11:291–5.

Miyamoto S, Muto M, Hamamoto Y, Boku N, Ohtsu A, Yoshida M, et al. A new technique for endoscopic mucosal resection with an insulated-tip electrosurgical knife improves the completeness of resection of intramucosal gastric neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:567–81.

Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929–42.

Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Nakamura M, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Ono S, et al. Successful outcomes of a novel endoscopic treatment for GI tumors: endoscopic submucosal dissection with a mixture of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid, glycerin, and sugar. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:243–9.

Gotoda T. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:1–11.

Yokoi C, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Oda I. Endoscopic submucosal dissection allows curative resection of locally recurrent early gastric cancer after prior endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:212–8.

Takenaka R, Kawahara Y, Okada H, Hori K, Inoue M, Kawano S, et al. Risk factors associated with local recurrence of early gastric cancers after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:887–94.

Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, Mouri R, Hirata M, Kanao H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for residual/local recurrence of early gastric cancer after endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2006;38:996–1000.

Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: technical feasibility, operation time and complications from a large consecutive series. Dig Endosc. 2005;17:54–8.

Ohnita K, Ishimoto H, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Nakamura T, Nishiyama H, et al. Factors related to the curability of early gastric cancer with endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2713–9.

Goto O, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Ono S, Omata M. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer with special reference to validation for curability criteria. Endoscopy. 2009;41:118–22.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–23.

Matsumoto A, Tanaka S, Oba S, Kanao H, Oka S, Yoshihara M, et al. Outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors accompanied by fibrosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1329–37.

Ono H, Yoshida S. Endoscopic diagnosis of the depth of cancer invasion for gastric cancer. Stomach Intest. 2001;36:334–40. (in Japanese with English abstract).

Murakami T, Matsui T, Koide H, Mochizuki T. Operative indication of gastric ulcer from a pathologic standpoint. Saishin-Igaku. 1959;14:1013–7. (in Japanese).

Oohara T, Tohma H, Aono G, Ukawa S, Kondo Y. Intestinal metaplasia of the regenerative epithelia in 549 gastric ulcers. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:1066–71.

Hytiroglou P, Tobias H, Saxena R, Abramidou M, Papadimitriou CS, Theise ND. The canals of Hering might represent a target of methotrexate hepatic toxicity. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:324–9.

Guang-Jin Y, Ming-Liang Z, Zuo-Jiong G. Effects of PPARg agonist pioglitazone on rat hepatic fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1047–51.

Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Muraki Y, Ono S, et al. Successful nonsurgical management of perforation complicating endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1001–6.

Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331–6.

Higashiyama M, Oka S, Tanaka S, Sanomura Y, Imagawa H, Shishido T, et al. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric epithelial neoplasm. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:290–5.

Onozato Y, Ishihara H, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Okamura S, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers and large flat adenomas. Endoscopy. 2006;38:980–6.

Zhang W, Tong Q, Chen Z, Gao Y, Jin S, Wang Q, et al. The usefulness of endoscopic ultrasound in the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant gastric ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1093–6.

Okada K, Fujisaki J, Kasuga A, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography is valuable for identifying early gastric cancers meeting expanded-indication criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:841–8.

Sanomura Y, Oka S, Tanaka S, Higashiyama M, Yoshida S, Arihiro K, et al. Predicting the absence of lymph node metastasis of submucosal invasive gastric cancer: expansion of the criteria for curative endoscopic resection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1480–7.

Sanomura Y, Oka S, Tanaka S, Noda I, Higashiyama M, Imagawa H, et al. Clinical validity of endoscopic submucosal dissection for submucosal invasive gastric cancer: a single-center study. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:97–105.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Higashimaya, M., Oka, S., Tanaka, S. et al. Outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm in relationship to endoscopic classification of submucosal fibrosis. Gastric Cancer 16, 404–410 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-012-0203-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-012-0203-0