Abstract

Introduction

Healthy elderly, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease populations have been among the most affected in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic due to the direct effects of the virus, and numerous indirect effects now emerge and will have to be carefully assessed over time.

Methods

This article reviews the main articles that have been published so far about the direct and indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on these particularly fragile populations.

Results

The pandemic associated to COVID-19 has shifted most of the health resources to the emergency area and has consequently left the three main medical areas dealing with the elderly population (oncology, time-dependent diseases and degenerative disease) temporarily “uncovered”. In the phase following the emergency, it will be crucial to guarantee to each area the economic and organizational resources to quickly return to the level of support of the prepandemic state.

Conclusions

The emergency phase represented a significant occasion of discussion on the possibilities of telemedicine which will inevitably become increasingly important, but all the limits of its use in the elderly population have to be considered. In the post-lockdown recovery phase, alongside the classic medical evaluation, the psychological evaluation must become even more important for doctors caring about people with cognitive decline as well as with their caregivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The novel coronavirus-2 (SARS-Cov-2) has spread all over the world starting from China in the beginning of 2020, and national health systems had, subsequently, to cope with primary and secondary hits from the SARS-Cov-2-related disease called COVID-19 (Table 1).

COVID-19 results in an outbreak of respiratory disease ranging from mild (a- or pauci-symptomatic) to fatal. Many patients require intensive care with ventilatory support. Critically ill patients suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are by definition hypoxemic, in need of mechanical ventilation and oxygen-therapy, as life-saving strategy. ARDS secondary to interstitial pneumonia is often complicated by multi-organ failure including cardiovascular, neurological, and neuromuscular symptoms requiring intensive care unit (ICU) intervention with ventilatory support.

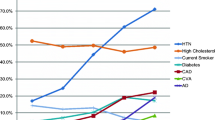

Elderly subjects with comorbidities—namely, hypertension, coronary artery disease, obesity, and diabetes—are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection with more severe symptoms and worse outcomes. Besides respiratory and cardiovascular problems, a number of COVID-19-related damages to nervous structures have been described: from smell/taste impairment to Guillain-Barre-Syndrome, from trigeminal neuralgia to a necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy [1, 2] and behavioral disturbances. Indeed, in some cases, mental confusion, delirium, and lethargy appeared before the classic symptoms of fever and respiratory distress. Coagulopathies with a pro-thrombotic condition and an inflammation-related “cytokine storm” may contribute to the multiorgan damage, including secondary effects on the nervous system [3,4,5].

Following the acute stage, a post-acute phase is often encountered characterized by a variety of sequelae combining problems stemming from respiratory, prolonged bedding, cardiovascular, and neurological (including cognitive/behavioral) complications which inhibit immediate home re-entry of patients from ICU and COVID-Units.

The great contagiousness of the virus and the high rate of serious and fatal complications has required extraordinary measures including progressive blocking of national borders, banning of non-urgent commercial and health activities, until the adoption of the complete lockdown, at the beginning in China, then in Italy and in Europe and subsequently all over the world. Secondary consequences of the pandemic have involved many chronic diseases, including dementia. Most of the health structures dedicated to follow-up of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other types of dementia have been down-graded in their activity given the need to implement safety protocols that limited patient access. Therefore, outpatient or day hospital activities have been severely reduced or totally closed for a period of about 3 months. Moreover, patients living in “resting homes” were progressively deprived of the physical visits of their relatives and friends due to safety protocols.

In Italy, which was one of the countries affected earlier and most impacted by the pandemic after China and where epidemiological data are available for a longer period of time, it has been described that COVID-19 lethality was less than 2.8% for people under 60 years, rose to 10.6% in the 60–69 age group, 26% in the 70–79 age group, and 32.8% in the 80-year-old group. Within the frame of the more than 36,000 people who died in Italy due to COVID-19, about 20% were between 70 and 79 and about 65% over 60 years of age [6]. The vast majority of them were defined “fragile elderly subjects,” namely, suffering from 2 or more chronic major diseases on top of which COVID-19 impacted as a final push to death. Although less clear, the data coming from the European Union [7], from the USA [8], and from Brazil [9] describe the same effects on different ages. Taken together, these data clearly define how the risk of severe and fatal complications is higher in the elderly population.

WHO Mental Health Department at the beginning of the pandemic recently released (January 2020) the document “Considerations on mental health and psychosocial well-being during the pandemic COVID-19” [10]. This document is mainly addressed to different groups of the population in support of their mental and psychosocial well-being, among which emerges a specific note to the elderly, caregivers and people with pre-existing diseases: “during the epidemic and quarantine, the elderly and people with cognitive impairment or dementia, especially if hospitalized in the structure, may experience greater anxiety, anger, stress, agitation or, vice versa, they can close themselves more in themselves.” For people with dementia, it can be difficult to fully understand and remind the reasons for this period of isolation, and the motivations leading to everyday life have so remarkable changes. For people with dementia, it can be difficult to fully understand and remind the reasons for this period of isolation and the motivations leading to so remarkable everyday life changes. Sometimes, in fact, a sudden change in behavior of the family members and of daily activities can trigger or amplify agitation and aggressive reactions in demented patients. Families and senior communities were not prepared to handle an emergency in the emergency and caregivers are likely to need additional education as well as stronger social, financial, and psychological support.

In our review we searched on PubMed, Google Scholar, and MedRxiv with the following key terms: “COVID-19,” “SARS-CoV2,” “Pandemic,” “human,” “Psychology,” “Psychiatry,” “Mental Health,” “Elderly,” “Fragile People,” Mild Cognitive Impairment,” “Alzheimer’s Disease,” and “Dementia”. Lately, some new reports related to COVID-19 and psychosocial impact on fragile populations as represented by normal elderly and dementia patients have been critically added.

Direct neurological consequences of COVID-19 on healthy elderly population and dementia

At present it is still unclear whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus, an RNA virus, has a direct neurotropic effect. To date, the virus is known to have several close sequence homologies with SARS-CoV-1 and both exploit the enzyme 2 receptor (ACE2) that converts angiotensin to mammalian cells as a binding site. After attachment to the host surface, the virus penetrates through the transmembrane protease serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) and the viral cycle begins. The viral cell tropism in humans is, therefore, mainly determined by the presence of the ACE2 receptor which is expressed in the airways, kidney cells, small intestine, pulmonary parenchyma, testicles, and vascular endothelium but also has a wide distribution in the central nervous system at the level of neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [11].

For what it concerns the brain, the ACE2 receptor was found in high concentrations in the mouse in substantia nigra, ventricles, middle temporal gyrus, posterior cingulate cortex, and olfactory bulb, as well as in the motor cortex and brain stem [12], and this distribution may explain some neurological complications in patients with COVID-19 as a result of possible entry pathways represented by the olfactory bulb and the vascular endothelium.

In a study by Mao et al. [13], it has been shown in 214 patients that the SARS-CoV-2 virus has a potential for penetration of the central nervous system. A percentage of COVID-positive patients had nonspecific neurological symptoms such as dizziness, headache, and seizures or more specific disorders such as loss of smell or taste and stroke. The way of entry into the brain was suggested to be the nasal olfactory epithelium through the cribriform plate, which can explain the first results of COVID-19 as an altered sense of smell or hyposmia; interestingly enough, this entry path is adjacent to brain areas that are most interested in the development of AD. On a collateral basis, it has also been reported how the SARS-CoV-2 virus can determine, alongside the respiratory infection, a neuroinflammatory state possibly triggering or accelerating neurodegeneration mechanisms and related symptoms including neuropsychiatric ones [14]. This hypothesis, which needs to be confirmed with appropriate follow-up, could possibly explain long-term indirect neurodegenerative effects in people over 65 years of age. To date, reports of neuro-psychiatric effects related to COVID-19 remain anecdotal, and log-term consequences are still far to be documented and need careful monitoring by the scientific community.

The effects of the SARS-COV-2 virus against specific populations of patients at risk can be considered according to 7 key parameters that have been proposed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Confirmed Cases, Fraction of Viral Positive, Hospitalizations, Emergency Department Visits, Reported Confirmed COVID-19, Deaths Excess Deaths, Representative Prevalence Surveys [15]. To date, no specific studies have demonstrated that the MCI or AD conditions increase the risk of a COVID-19 infection and higher fraction of viral positive population, but increased age and associated health conditions such as dementia may increase the risk in this vulnerable population. People affected by AD may forget common measures for lowering the risk of infection as washing their hands, social distance, and face masks or taking other necessary precautions. The Center for Disease Control of the USA [8] has proposed particularly strict risk reduction measures for people with a history of dementia with specific suggestions such as reminders useful for remembering the main hygiene every day practices, putting alerting signals in the bathroom and elsewhere to remind to wash hands with soap for 20 s and to wear a face mask to cover nose and mouth.

As a result of the infection, older people with dementia develop a more serious disease with more severe symptoms. Although accurate estimates of the mortality rate associated with this disease do not yet exist, it appears that the access rate in emergency facilities, hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19 may be higher in the AD population than in elderly non-demented one. In fact, it should be taken into account that advanced age and concomitant disabling medical conditions such as heart or lung disease or diabetes increase the risk of severe progression and death by COVID-19, which often follows serious effects on the lungs and this condition may still worsen in institutionalized elderly.

Interestingly, it was also hypothesized [16] that two commonly used drugs for Parkinson (amantadine) and AD (memantine) might play a protective role against SARS-CoV-2 infection through an inhibition of neurotoxicity and viral replication with slowing of the pathological phenomenon that leads to the development of ARDS. This is because of the role of memantine, which acts as a non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor (NMDA) antagonist by preventing excess calcium in cells. This property, useful in the treatment of Alzheimer’s patients, is similar to that of amantadine, which is used in tremor associated with Parkinson’s disease and could have antiviral potential. Although suggestive, this hypothesis still needs to be confirmed.

As detailed in the interesting review report by Fotuhi et al. [17], the function of ACE2 in normal human physiology is to regulate blood pressure via inhibition of the angiotensin-renin-aldosterone pathways [18]. ACE2 facilitates conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin, and higher levels of angiotensin II are associated with vasoconstriction, kidney failure, heart disease, apoptosis, and oxidative processes that accelerate aging and promote brain degeneration [18]. ACE2 deficiency lessens the impact of SARS-Cov2 infection [19]. After binding ACE2 in respiratory epithelial cells and then epithelial cells in blood vessels, SARS-Cov2 triggers the formation of a cytokine storm, with marked elevation in levels of interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor [20, 21].

High levels of these cytokines increase vascular permeability, edema, and widespread inflammation with consequent damage in cellular mechanism for energy production (mitochondria) and protein folding [22]. SARS-Cov2, as well as other corona viruses, can remain inside some neurons without being acutely toxic [1]. The abnormal misfolding and aggregation of proteins in patients who survive and recover from their acute SARS-Cov2 infection can thus theoretically lead to brain degeneration decades later [22]. It is, in fact, likely that the cytokine storm and the insults to the brain via small or large strokes, a damage to Blood-Brain-Barrier (BBB) and high levels of inflammation inside the brain would have long-term neuropsychiatric consequences. The cytokine storm in COVID-19 can cause a series of small punctate strokes without causing immediate neurological deficits [23]. When these patients leave the hospital after an acute SARSCov2 infection, they may experience poor memory, attention, or slow processing speed. Thus, it would be helpful for these patients to see a neurologist or undergo neurocognitive testing 6–8 months after their hospital discharge if they feel they still have cognitive issues, slowness in processing information, or poor attention. Patients with low scores in certain cognitive domains can consider receiving specific rehabilitation in order to return to their baseline level of cognitive capacity. By doing so, they would reduce their risk for developing a worse case of age-related cognitive decline later in life [24].

Ethical considerations regarding COVID-19 and fragile patients with dementia

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that the huge impact of COVID-19 on emergency departments would lead to the application of severe measures previously adopted during war or natural disasters. Most of the COVID-related national guidelines reflect a shift in prioritization of ethical principles guiding clinical decisions under conditions of limited resources, such as during the current COVID-19 pandemic. Whereas in everyday medical practice, with sufficient resources, principles such as universal access, minimizing harm, patient autonomy and proportionality of benefits and harm are pivotal, during COVID-19 emergency priorities shift toward maximizing benefits and balancing the distribution of scarce resources.

The impact of the disease on emergency wards was especially important during the first phase of the pandemic in which the request for beds and life-supporting interventions (i.e., mechanical ventilation with full-head masks) in advanced emergency wards and ordinary therapy had been far greater than their availability and therefore measures to regulate the allocation of the available resources were adopted. An analysis of the journal Financial Times after the first 3 months of the pandemic has established that the region of northern Italy in Lombardy and in particular the region of Bergamo had recorded an increase in mortality for the same period in previous years of over 660%, for a really sad record that placed it in first place in the world and third in history after the city of Miyagi in Japan during the 2011 tsunami (685%) and the city of Philadelphia during the Spanish Flu of 1918 [25].

The impact of a large number of patients on emergency care departments has prompted many scientific societies to take measures to “optimize” the resources available in terms of medical equipment and personnel. The first guidelines were released by the Israeli resuscitation society indicating that all people affected by severe forms of COVID-19 must be guaranteed with adequate palliative care even if clinically compromised and with dementia and as far as possible [26]. A document from some of the Italian anesthesia and resuscitation societies proposed measures to be taken during the triage in emergency department that took into account factors such as age, comorbidities, and the functional status of any critically ill patient potentially admitted in order to maximize the benefits for the largest number of people [27].

Jobges and Coll. (2020) [28] carefully compared triage guidance documents which have been developed or adapted from former influenza pandemic guidelines in an increasing number of countries over the past few months. In this article, they provide a comparative analysis of triage recommendations from selected national and international professional societies, including Australia/New Zealand, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Pakistan, South Africa, Switzerland, the USA, and the International Society of Critical Care Medicine. Triage plans often depend on the degree of resource constraints [29]. All guidance documents emphasize that triage decisions only apply in the case of a lack of resources that preclude taking care of all patients at the best of the present knowledge. Reference to the principle of justice can be found in all guidance. The principle of equality is invoked by stipulating that triage decisions should apply to all patients with the same prognosis, with or without COVID-19. Equitable access to healthcare is described in the sense that there should be no discrimination on grounds of characteristics such as age, race, sexual orientation, disability, or socioeconomic status. Various scores are recommended to assess mortality risk and to estimate the probability of survival. Some guidelines use the sequential organ failure assessment score (SOFA), while others discuss or reject the SOFA score because it has not been validated for the COVID-19 pandemic. The clinical frailty scale is also proposed as a tool for estimating the general clinical condition. For instance, the presence of severe comorbidities may exclude patients from ICU in the UK. To identify those patients who would benefit most from the scarce interventions, it is suggested to take into account the probabilities of short-term survival (with all the limitations of the relatively little knowledge about COVID-19) and some determinants of long-term survival (38) including comorbidities, lifespan considerations, and the patient’s current clinical condition. Transparency in decision-making, which is explicitly mentioned in most guidelines, is defined as providing an “open flow” of information for public access helping the public to understand how and why certain decisions are made in clinical settings.

Ethical checklist (modified by Jobges et al. 2020 [28]):

-

a

Include all patients, new and current, COVID and non-COVID, in triaging considerations.

-

b

Do not discriminate by age, race, disability, sexual orientation, religion, insurance status, wealth, and social status and pay due attention to vulnerable groups (older adults, minorities, people with disabilities).

-

c

There must be a clear definition of maximizing benefit in the different stages of scarcity. It is important to distinguish between first-order criteria (e.g., short-term survival) and second-order criteria (e.g., long-term survival) that are used when there is a tie [30]. Also, flag criteria that should not be used.

-

d

Develop a procedure to distinguish different levels of scarcity (e.g., limited availability of ICU beds versus no ICU beds available) and the implications for decision-making (e.g., admission triage versus resource management through discontinuation of treatment).

-

e

Define a consistent assessment of short-term and/or long-term survival through medical criteria, tests, and validated prediction scores.

-

f

Perform regular re-evaluation, including available resources and clinical development, preferably by an independent triage committee rather than by the treatment team; rules for deciding on withdrawing or withholding therapy should be transparent and designed to “minimize bias and avoid unintended negative consequences.”

-

g

Consider patient wishes when making decisions, which in triage cases is largely limited to respecting a refusal of ICU therapy. Information about likely outcome and burden of treatment should be reviewed with the patient or with surrogate decision-makers in advance (advance care planning).

-

h

Ensure palliative/supportive care availability for intensive care receive non-intensive medical care and, if appropriate, palliative care [9].

-

i

Provide adequate protection of personnel in this physically and psychologically stressful situation.

-

j

Review and evaluate triage guidance after and during the ongoing pandemic in order to create learning opportunities and trust.

Indirect consequences on elderly population and dementia

It is estimated that over 50 million live with dementia worldwide [31]. In Italy, the total number of patients with dementia is estimated at over one million (of which approximately 600,000 with Alzheimer’s dementia), and approximately 3 million people are directly or indirectly involved as caregivers. During the emergency related to COVID-19, this population was particularly at risk because it was made up of people of advanced age, with limited access to the technological information available through the media and the Web. Such frailty population often lives alone or in medium- and long-term senior houses which were among the places at greatest risk for rapid viral diffusion and unfavorable outcome [32].

A crucial factor to consider in older people in general, and in particular in people with MCI or AD, is to understand what might be responsible for effects greater than the direct effects of the virus for the severity enhancement of pre-existing medical clinical conditions in COVID survivors. For these reasons, it seems appropriate that people who have been affected by SAARS-COV-2 continue for a long period of time medical follow-up aiming to early detection of any alteration in the clinical course of the pathologies from which they were affected before the viral infection [33].

During the pandemic, a crispy scientific discussion was represented by the opportunity or not to socially isolate those people at risk in long-term residential structures with contact restrictions with the outside world in order to limit the diffusion of the infection. A survey carried out in Italy in residential structures that host AD patients [34] revealed that in March 2020 the mortality compared with the same month in previous years was +94%, with peaks of almost +300% in Lombardy, one of the regions most affected. In many small towns in southern Italy where the outbreaks were scarce or non-existent, the presence of a senior house for AD patients was the main factor identified in turning the whole area into a red area.

Patients with severe cognitive impairment due to AD and related dementias therefore represent one of the populations at greatest risk of negative outcomes during quarantine. The decline in cognitive functions and the inevitable impact of pathology on quality of life also have serious effects on the family and on the informal caregiver (someone—family member, relative, or friend—who assists the sick person at home). The wish of stay close to relatives, to allow the patient to continue living in his own residence, and the perception of feeling obliged to take care of them are the main factors behind the choice to assist at home. The caregiver condition, however, is associated with a significant deterioration in quality of life and with an increased risk of disease and death [35].

An integrated assessment of the health of elderly people with initial and advanced forms of dementia should take into account the drugs that are taken daily and their possible effect on the course of COVID-19 infection. All chronic diseases must be considered and it should not be forgotten that all these conditions continue to progress even during the pandemic phase and in the following period. It must be considered that also health aspects that are taken for granted in younger people may not be so for elderly people such as a correct management of nutrition with a correct intake of water and food, a correct amount of daily physical and cognitive exercise, and a correct management of daily pharmacological therapies and medical devices; all these items and the psychological well-being of frail elderly people must be particularly taken into account [36]. Elderly frail subjects should therefore never be left alone and it is necessary to implement remote monitoring systems for all these chronic medical conditions with particular attention to people who have been infected with the virus.

Impact of COVID-19 on dementia research

Protective measures for laboratory research operators totally blocked during the lockdown studies on transgenic animals with important economic consequences. It should not be forgotten that public health systems and private companies involved in research must and will have to face the economic consequences of this period in the immediate future and it is plausible to think of a period in which investments will be reduced. Data loss in research studies is at the forefront of indirect problems associated with the COVID-19 epidemic [37].

A paradigmatic picture of the COVID-related emergency situation and its impact on research protocols can exemplified by the INTERCEPTOR project in Italy, a multicenter study that aims to determine at an early stage the biomarkers associated with early conversion from MCI ad AD and involves 25 centers (20 recruiting centers and 5 expert centers) distributed throughout the whole national territory [38]. The first problems with recruitment began in February 2020 rapidly progressing toward a complete cessation of activities starting from 9 March, the date on which the complete Lockdown was declared in Italy, and subsequent initial and slow resumption of activities in June. Meanwhile, many candidates and caregivers do not want to come to hospitals for the recruitment/follow-up visits as well as for the acquisition of the biomarkers under study. A report of the difficulties encountered and the solutions adopted is currently being developed for future considerations in the data analysis phase.

Many expected phase 2/3 clinical trials such as that relating to Gantenerumab (Roche) and Solanezumab (Lilly) should give expected results in this period [39], but it is possible that there are variable shifts depending on future developments in the global social framework.

In this area there have been many rumors in favor of a prudent and controlled reopening of the AD research centers for clinical and preclinical studies. Although safety of operators and patients must be taken into high-priority account, the enormous social and economic impact of a prolonged closure of research facilities over time must also be considered.

In the reopening mechanisms, an important role is played by telemedicine methods through telephone interviews and video consultations aimed at checking the expected results during the follow-up. Certainly, a complicated aspect is represented by the screening visits which have suffered heavy losses due to the lockdown and will require a precise reformulation in all the clinical studies currently underway and about to start [40, 41].

Telemedicine in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia has already demonstrated an excellent development potential, especially as regards to the follow-up phase, while indications are still limited in the setting up of the therapeutic path. Several limitations should be considered including the lack of efficient Internet connection throughout the territory, little familiarity with the information and Communication Technology (ICT) facilities by older people and their relatives, the presence of sensory deficits in elderly people such as visual disturbances, or hearing disorders that can make technological contact difficult. In addition, it must be considered that in this population of fragile patients, human contact remains a fundamental tool for continuing the therapeutic and rehabilitative path [42, 43]. Telemedicine is a tool that needs some implementations, but this system can be of huge help to bring clinical trials forward. Another important aspect concerns experimental drug administration; in fact, most of the studies are based on the intravenous administration, a method no longer considered fully safe in hospital during this COVID pandemic. The implementation of an alternative system of drug delivery and at home administration will be necessary to continue all experimental activities of pharmacological trials [44].

Both EMA and FDA [45, 46] released official documents asking to different stakeholders involved in clinical trials to respect national legislation and to put people’s safety before any situation of possible conflict. For ongoing trials, there it should be considered a longer duration to be agreed with national authorities for drug approval, for sponsors and investigators and to continue to always report possible adverse events. The details of the closure and reopening must be adequately detailed and taken into account in the discussion of the results.

The totally new situation that we are living has also been acknowledged by the main scientific journals that deal with this area, and guidelines have been proposed on the conduct of clinical studies during this phase. For example, it was proposed that clinical trials should be suspended to ensure the safety of participants and both sponsors and investigators should take charge of communication as adequate as possible with the enrolled subjects. In view of the complexity of the research networks that are involved in these researches, public/private funding companies must collaborate toward reopening plans and safeguard the correctness of scientific information. In processing the data, it was necessary to take into account the impossibility of keeping the dates of the follow-up visits within the time windows, and these difficulties had to be considered and discussed in the monitors’ meetings. It is up to the review boards for the various clinical trials to decide and apply measures that safeguard data security and integrity as much as possible. Since many of the studies dedicated to Alzheimer’s disease are very long in time and very expensive, the problem of missing data must also be assessed. The major scientific associations involved in ensuring research on Alzheimer’s disease encourage the publication of methodologies with which the various research groups are statistically addressing these problems [47].

Impact of COVID-19 on psychiatric health of patients with cognitive decline and their caregiver

In a recent review on this topic, Brooks et al. [48] have underlined how the negative quarantine effects represented by anger and post-traumatic disorder are associated with negative determinants which can be summarized in the following list: quarantine duration, infection fears, frustration, boredom, inadequate supplies, inadequate information, financial loss, and stigma with possible long-lasting effects.

It has also been reported by Ward C.F. and colleagues [49] that an altered mental status of acute onset may be an heralding symptom of COVID-19. In their report, the authors described 4 different cases of people who had already received a diagnosis of dementia in which confusion, agitation, and disorientation appeared before other respiratory symptoms or fever. In all cases, the search for the viral genome using a nasopharyngeal swab tested positive and all the patients analyzed would have developed radiologically evident pneumonia in a period of 3–7 days and respiratory complications which in 2 out of 4 patients were of high severity.

The public health measures put in place so far to face the pandemic have required social isolation which have proven to be the only truly effective prevention strategy [50]. As the advance of the virus continues all over the world involving also the USA, India, and developing countries and producing a “second strike” in Europe, the social impact of these measures is still far from being fully understood [30, 51,52,53,54], but there is a serious risk that for some population groups, this condition will worsen the state of solitude. Specific questionnaires have been proposed aimed at investigating how the social isolation has influenced communication with other people who play an important role in the daily lives of elderly and demented subjects, starting from the doctor to relatives.

A survey conducted in the Chinese population [55] showed an increase in long-term care insurance (LTCI) purchase intentions from elderly people from 25 to 38% after the COVID-2019 epidemic as an indirect demonstration of an increased perception that the end of life is approaching. These data were particularly marked for people with initial forms of cognitive impairment, who had received the diagnosis in recent times and—because of such diagnosis—had already modified their lifestyle and for whom the COVID-19 effect represented a further rapid phase of decline.

The psychological impact of the pandemic was first investigated in China, in the Gansu region, during the first phase of the emergency; health workers were examined in order to understand the prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression and any coping strategies for negative emotions [56]. With the use of specific questionnaires, a prevalence of anxiety of 11% and depression of 46% in doctors and 28 and 43.0% in nurses emerged. Such symptoms were more frequent in women and in those who had already experienced psychological symptoms before the pandemic. It also emerged that the adoption of positive coping styles tended markedly to improve negative emotions.

In a Spanish study [57], 40 subjects diagnosed with MCI (20) or mild AD (20) who had performed neuropsychological and clinical assessment during the month prior to the lockdown were re-evaluated after 5 weeks of social isolation via the neuropsychiatric scale (NPI) and EuroQol- 5D. The total basal NPI score worsened by about 6 points, from 33.75 to 39.05 after confinement, with the appearance of various neuropsychiatric symptoms including apathy and anxiety in subjects with MCI and apathy, agitation, and aberrant motor behavior in AD patients. Globally, both patients and their caregivers worsened in about 40% of cases.

Changes in the daily life habits of older people with an interruption of social activities such as the maintenance of public areas as well as volunteering within the community, sports, or other leisure activities could also have a more important impact on older people because they have developed their own daily routine to fill-up empty spaces left by the lack of working and family duties. The psychological impact of the lockdown could be even tougher for people who have been hospitalized during this period, because of the separation from their loved ones, leading to despair and feelings that the world is ending. A possible solution for all these different situations can be represented by the adoption of coping strategies through techniques that use cognitive and behavioral supports and with the help of qualified personnel to manage anxiety and stress caused by the pandemic [58, 59].

Recently, Cagnin and Coll. [60] reported an extended survey on the effect of COVID-related lockdown in Italy. They showed that quarantine induces a rapid increase of BPSD in approximately 60% of patients and stress-related symptoms in two-thirds of caregivers and concluded that health services need to plan a post-pandemic strategy in order to address these emerging needs.

Zhou and Coll. [61] investigated the impacts of COVID-19 on cognitive functions in patients who recovered from the viral infection and its relationship with inflammatory profiles. The cognitive functions of all subjects were evaluated by the iPad-based online neuropsychological tests, including the Trail Making Test, Sign Coding Test, Continuous Performance Test, and Digital Span Test. Blood samples were collected for examining inflammatory profiles, including interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ, and C-reactive protein. They concluded that cognitive impairments exist even in patients recovered from COVID-19 and might be possibly linked to the underlying inflammatory processes. This result as previously said supports the idea that a follow-up in recovered COVID subjects is needed to track eventual signs of neurodegenerative cognitive decline.

Conclusions

The pandemic associated to COVID-19 has shifted most of the health resources to the emergency area and has consequently left the three main medical areas that affect the elderly population (oncology, time-dependent diseases, and degenerative disease) temporarily “uncovered.” In the phase following the emergency, it will be crucial to guarantee to each area the economic and organizational resources to quickly return to pre-pandemic state. It must be considered that even people who have not been directly affected by the viral infection may suffer from indirect effects related to the worsening of the background medical condition, to delay of control visits due to organizational difficulties (related to structures and staff), and for the fear of coming in contact with hospitals that have been seen as a major source of infection. The emergency phase represented an important occasion of discussion on the possibilities of telemedicine which will inevitably become increasingly important even if the problems related to an optimal use by elderly population will have to be resolved and all the limits of an evaluation in which there is not direct contact with the patient must be considered. In the post-lockdown recovery phase, alongside the classic medical evaluation, the psychological and cognitive evaluation—with which doctors need to become more familiar—and the use of specific professional figures will have to find ample space, in order to follow-up and to better understand all the consequences on elderly population that are still not completely evident.

Data availability

No dataset was used for writing this work. Data used to draft this article can be shared upon request to the Corresponding author.

References

Nath A (2020) Neurologic complications of coronavirus infections. Neurology 94:809–810. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009455

Baig AM (2020) Neurological manifestations in COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2. CNS Neurosci Ther 26:499–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13372

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z (2020) Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 18:844–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14768

Han H, Yang L, Liu R, Liu F, Wu KL, Li J, Liu XH, Zhu CL (2020) Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med 58:1116–1120. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2020-0188

Wu L, O’Kane AM, Peng H et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 and cardiovascular complications: from molecular mechanisms to pharmaceutical management. Biochem Pharmacol 178:114114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114114

Kontis V, Bennett JE, Rashid T et al (2020) Magnitude, demographics and dynamics of the effect of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on all-cause mortality in 21 industrialized countries. Nat Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1112-0

Alvarez M (2020) COVID-19 cases and case fatality rate by age. In: Knowledge for policy. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/publication/covid-19-cases-case-fatality-rate-age_en. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

CDC (2020) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) – prevention & treatment. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Coronavírus Brasil. https://covid.saude.gov.br/. Accessed 22 Jun 2020

Coronavirus. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T et al (2020) Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: a review. JAMA Neurol 77:1018–1027. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065

The spatial and cell-type distribution of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in human and mouse brain | bioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.07.030650v1. Accessed 22 Jun 2020

Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X, Li Y, Hu B (2020) Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 77:683–690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127

Hascup ER, Hascup KN (2020) Does SARS-CoV-2 infection cause chronic neurological complications? GeroScience 42:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-020-00207-y

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2020) Evaluating data types: a guide for decision makers using data to understand the extent and spread of COVID-19. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Brenner SR (2020) The potential of memantine and related adamantanes such as amantadine, to reduce the neurotoxic effects of COVID-19, including ARDS and to reduce viral replication through lysosomal effects. J Med Virol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26030

Fotuhi M, Mian A, Meysami S, Raji CA (2020) Neurobiology of COVID-19. J Alzheimers Dis 76:3–19. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200581

Kai H, Kai M (2020) Interactions of coronaviruses with ACE2, angiotensin II, and RAS inhibitors—lessons from available evidence and insights into COVID-19. Hypertens Res 43:648–654. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0455-8

Verdecchia P, Cavallini C, Spanevello A, Angeli F (2020) The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Intern Med 76:14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037

Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, HLH Across Specialty Collaboration, UK (2020) COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 395:1033–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0

Xiong M, Liang X, Wei Y-D (2020) Changes in blood coagulation in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Br J Haematol 189:1050–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16725

Lippi A, Domingues R, Setz C, Outeiro TF, Krisko A (2020) SARS-CoV-2: at the crossroad between aging and neurodegeneration. Mov Disord 35:716–720. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.28084

Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Kummerlen C, Collange O, Boulay C, Fafi-Kremer S, Ohana M, Anheim M, Meziani F (2020) Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med 382:2268–2270. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2008597

Fotuhi M, Hachinski V, Whitehouse PJ (2009) Changing perspectives regarding late-life dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 5:649–658. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2009.175

McCann A, Wu J, Katz J (2020) How the coronavirus compares with 100 years of deadly events. The New York Times. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Clarfield AM, Dwolatzky T, Brill S, Press Y, Glick S, Shvartzman P, Doron I(I) (2020) Israel ad hoc COVID-19 committee: guidelines for Care of Older Persons during a pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc 68:1370–1375. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16554

Vergano M, Bertolini G, Giannini A et al (2020) Clinical ethics recommendations for the allocation of intensive care treatments in exceptional, resource-limited circumstances: the Italian perspective during the COVID-19 epidemic. Crit Care 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02891-w

Jöbges S, Vinay R, Luyckx VA, Biller-Andorno N (2020) Recommendations on COVID-19 triage: international comparison and ethical analysis. Bioethics. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12805

Gopalan PD, Pershad S (2019) Decision-making in ICU – a systematic review of factors considered important by ICU clinician decision makers with regard to ICU triage decisions. J Crit Care 50:99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.11.027

Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha M, Agha R (2020) The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg 78:185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018

Wang H, Li T, Barbarino P et al (2020) Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet 395:1190–1191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30755-8

Wang H, Li T, Barbarino P, Gauthier S, Brodaty H, Molinuevo JL, Xie H, Sun Y, Yu E, Tang Y, Weidner W, Yu X (2020) Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet 395:1190–1191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30755-8

Palmer K, Monaco A, Kivipelto M, onder G, Maggi S, Michel JP, Prieto R, Sykara G, Donde S (2020) The potential long-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on patients with non-communicable diseases in Europe: consequences for healthy ageing. Aging Clin Exp Res 32:1189–1194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01601-4

Palmieri L, Vanacore N, Donfrancesco C, Lo Noce C, Canevelli M, Punzo O, Raparelli V, Pezzotti P, Riccardo F, Bella A, Fabiani M, D’Ancona FP, Vaianella L, Tiple D, Colaizzo E, Palmer K, Rezza G, Piccioli A, Brusaferro S, onder G, Italian National Institute of Health COVID-19 Mortality Group, Palmieri L, Andrianou X, Barbariol P, Bella A, Bellino S, Benelli E, Bertinato L, Boros S, Brambilla G, Calcagnini G, Canevelli M, Rita Castrucci M, Censi F, Ciervo A, Colaizzo E, D’Ancona F, del Manso M, Donfrancesco C, Fabiani M, Facchiano F, Filia A, Floridia M, Galati F, Giuliano M, Grisetti T, Kodra Y, Langer M, Lega I, Lo Noce C, Maiozzi P, Malchiodi Albedi F, Manno V, Martini M, Mateo Urdiales A, Mattei E, Meduri C, Meli P, Minelli G, Nebuloni M, Nisticò L, Nonis M, onder G, Palmisano L, Petrosillo N, Pezzotti P, Pricci F, Punzo O, Puro V, Raparelli V, Rezza G, Riccardo F, Cristina Rota M, Salerno P, Serra D, Siddu A, Stefanelli P, de Bella MT, Tiple D, Unim B, Vaianella L, Vanacore N, Vichi M, Rocco Villani E, Zona A, Brusaferro S (2020) Clinical characteristics of hospitalized individuals dying with COVID-19 by age Group in Italy. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75:1796–1800. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa146

Chiao C-Y, Wu H-S, Hsiao C-Y (2015) Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev 62:340–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12194

Abbatecola AM, Antonelli-Incalzi R (2020) Editorial: COVID-19 spiraling of frailty in older Italian patients. J Nutr Health Aging 24:453–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1357-9

Bostanciklioglu M (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is penetrating to dementia research. Curr Neurovasc Res 17. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202617666200522220509

Rossini PM, Cappa SF, Lattanzio F, Perani D, Spadin P, Tagliavini F, Vanacore N (2019) The Italian INTERCEPTOR project: from the early identification of patients eligible for prescription of antidementia drugs to a Nationwide organizational model for early Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. J Alzheimers Dis 72:373–388. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190670

Geerts H, van der Graaf PH (2020) Salvaging CNS Clinical Trials halted due to COVID-19. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp4.12535

Geerts H, van der Graaf PH (2020) Salvaging CNS clinical trials halted due to COVID-19. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 9:367–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp4.12535

Ousset PJ, Vellas B (2020) Viewpoint: impact of the Covid-19 outbreak on the clinical and research activities of memory clinics: an Alzheimer’s disease center facing the Covid-19 crisis. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis 7:197–198. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2020.17

Costanzo M, Signorelli M, Aguglia E (2014) EPA-0715 – telemedicine and Alzheimer: a systematic review. Eur Psychiatr 29:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(14)78073-3

Cuffaro L, Di Lorenzo F, Bonavita S et al (2020) Dementia care and COVID-19 pandemic: a necessary digital revolution. Neurol Sci 41:1977–1979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04512-4

Francisco EM (2020) Guidance to sponsors on how manage clinical trials during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/guidance-sponsors-how-manage-clinical-trials-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

Research C for DE and (2020) COVID-19: developing drugs and biological products for treatment or prevention. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/covid-19-developing-drugs-and-biological-products-treatment-or-prevention. Accessed 16 Nov 2020

(2020) Alzheimer’s Disease Research Enterprise in the Era of COVID‐19/SARS‐CoV‐2. Alzheimers Dement 16:587–588. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12093

(2020) Alzheimer’s Disease Research Enterprise in the Era of COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2. Alzheimers Dement 16:587–588. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12093

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395:912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Ward CF, Figiel GS, McDonald WM (2020) Altered mental status as a novel initial clinical presentation for COVID-19 infection in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28:808–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.013

Cawthon P, Orwoll E, Ensrud K et al (2020) Assessing the impact of the covid-19 pandemic and accompanying mitigation efforts on older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75:e123–e125. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa099

Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Lahiri D, Lavie CJ (2020) Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr 14:779–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035

Rajkumar RP (2020) COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr 52:102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

Buonsenso D, Cinicola B, Raffaelli F, Sollena P, Iodice F (2020) Social consequences of COVID-19 in a low resource setting in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Int J Infect Dis 97:23–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.104

Chetterje P (2020) Gaps in India’s preparedness for COVID-19 control. Lancet Infect Dis 20:544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30300-5

Xu X, Zhang L, Chen L, Wei F (2020) Does COVID-2019 have an impact on the purchase intention of commercial long-term care insurance among the elderly in China? Healthcare (Basel) 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020126

Zhu J, Sun L, Zhang L, Wang H, Fan A, Yang B, Li W, Xiao S (2020) Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms in the first-line medical staff fighting against COVID-19 in Gansu. Front Psychiatry 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00386

Lara BB, Carnes A, Dakterzada F et al (2020) Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Spanish Alzheimer’s disease patients during COVID-19 lockdown. Eur J Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14339

Thoits P (1995) Stress, coping, and social support processes - where are we - what next. J Health Soc Behav 35:53–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626957

Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M, Crockett MJ, Crum AJ, Douglas KM, Druckman JN, Drury J, Dube O, Ellemers N, Finkel EJ, Fowler JH, Gelfand M, Han S, Haslam SA, Jetten J, Kitayama S, Mobbs D, Napper LE, Packer DJ, Pennycook G, Peters E, Petty RE, Rand DG, Reicher SD, Schnall S, Shariff A, Skitka LJ, Smith SS, Sunstein CR, Tabri N, Tucker JA, Linden S, Lange P, Weeden KA, Wohl MJA, Zaki J, Zion SR, Willer R (2020) Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav 4:460–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

Cagnin A, Di Lorenzo R, Marra C et al (2020) Behavioral and psychological effects of coronavirus Disease-19 quarantine in patients with dementia. Front Psychiatr 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.578015

Zhou H, Lu S, Chen J, Wei N, Wang D, Lyu H, Shi C, Hu S (2020) The landscape of cognitive function in recovered COVID-19 patients. J Psychiatr Res 129:98–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.06.022

Acknowledgments

We would like to dedicate this work to the INTERCEPTOR study group who continued to support subjects with MCI and patients with AD and their family during the difficult COVID-19 time. We also thank all the healthcare workers who are keeping to serve in long-term residences and the associations of families who are spreading important informations to all the community of people with dementia and their caregivers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors drafted and critically revised this work. All the authors declare to approve the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no conflicts relevant to this manuscript.

Ethical approval

None.

Informed consent

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iodice, F., Cassano, V. & Rossini, P.M. Direct and indirect neurological, cognitive, and behavioral effects of COVID-19 on the healthy elderly, mild-cognitive-impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease populations. Neurol Sci 42, 455–465 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04902-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04902-8