Abstract

The construction of traditional finite element geometry (i.e., the meshing procedure) is time consuming and creates geometric errors. The drawbacks can be overcame by the Isogeometric Analysis (IGA), which integrates the computer aided design and structural analysis in a unified way. A new IGA beam element is developed by integrating the displacement field of the element, which is approximated by the NURBS basis, with the internal work formula of Euler-Bernoulli beam theory with the small deformation and elastic assumptions. Two cases of the strong coupling of IGA elements, “beam to beam” and “beam to shell”, are also discussed. The maximum relative errors of the deformation in the three directions of cantilever beam benchmark problem between analytical solutions and IGA solutions are less than 0.1%, which illustrate the good performance of the developed IGA beam element. In addition, the application of the developed IGA beam element in the Root Mean Square (RMS) error analysis of reflector antenna surface, which is a kind of typical functional surface whose precision is closely related to the product’s performance, indicates that no matter how coarse the discretization is, the IGA method is able to achieve the accurate solution with less degrees of freedom than standard Finite Element Analysis (FEA). The proposed research provides an effective alternative to standard FEA for shape error analysis of functional surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Functional surface is a type of complex surface, which is ubiquity in mechanical and electrical equipment, realizes specific physical performances, such as electric, magnetic, optic and thermodynamic performance. The accuracy of functional surface, which is the critical function structure of a product, has a significant impact on the product’s performance. Antenna surface is a kind of typical functional surface, which realizes transmitting and receiving of electromagnetic signal. As in the case of reflector antenna where the reflector surface is such a functional surface, the influences on reflector surface precision from external loads, manufacturing and assembling errors [1–5] are considerable in changing the amplitude and phase distribute of antenna aperture to affect the far electric field of antenna. And the surface root mean square (RMS) of half-path-length error is always adopted to estimate the gain degradation according to the Ruze equation [6]. In recent years, more and more large reflector antennas are equipped with shape control systems to estimate the surface errors. TANAKA [7] added intentional deformations on an antenna surface using the surface adjustment mechanisms to estimate the surface errors. And a dynamic shape control strategy of deployable mesh reflectors via feedback approaches was proposed by XIE, et al [8]. Other adjustment strategies have been investigated by several researchers [9–11]. In order to get the control inputs to actively adjust the surface shape, measurement methods and numerical simulations are adopted to estimate the surface error. The phase-retrieval holographic analysis [12, 13], photogrammetry measurements [14], etc. are widely used to measure shapes of reflector antennas. Although measurement methods could easily acquire the surface displacement distribution, the measure accuracies rely on the special equipment and the antenna’s wavelength. The numerical simulations, Finite Element Analysis(FEA), are good alternates in shape error analysis due to the advantage in optimization of the initial prototype designs. YOON [15] formulated a shape error minimization problem for a mechanically deformable reflector antenna structure in the frame work of the FEA. YOU, et al [16], used a 3-nodes laminated shell element based on Lagrange’s equations to study the characteristics of the reflector. DU, et al [17], employed the FEA to calculate the sensitivity matrix of the nodal displacement to deal with the worst-case optimization problem of cable mesh reflector antenna. However, only the displacements of the elements nodes can be applied to calculate the RMS error since the points in the element have inherent discretization errors which are especially bad for surfaces with a relatively coarse mesh. Refined mesh is required to improve the simulation accuracy, which would in turn makes the calculation more time consuming.

Isogeometric analysis (IGA) [18] is a method aimed at avoiding the discretization errors by using the same basis for analysis as is used to describe the geometry, thus enabling IGA to discretize the analysis models exactly. The necessary continuities between elements, C 1 continuity for Kirchhoff-Love element as an example, can be easily achieved by the high-order geometric basis functions. The method is now further developed in many areas including structural analysis [19–21], fluid-structure interaction [22], shape optimization [23, 24], topology optimization [25, 26], electromagnetic analysis [27], etc.. New IGA elements [28, 29] are developed by researches. However, the non-interpolatory nature of the geometric basis functions makes the imposition of even the simple boundary conditions more difficult. Weak and strong methods are studied to the coupling [30–32] and boundary condition imposition issues [33, 34] to perfect the novel method. The method is now capable to deal with the majority of engineering issues. The exact geometric discretization of IGA enables us to achieve more accurate solutions by much less degrees of freedom than that of traditional FEA.

The paper is organized as follows. In section 2, a brief introduction of the surface error estimation is presented, include the relationship between the RMS half-path-length error and antenna gains, the normal deviation, etc. In section 3, a rotation-free three-dimensional IGA beam element combined with Bézier extraction is developed, and a Kirchhoff-Love shell element is also introduced in brief. Then the coupling of the two elements is presented. Moreover, at the end of the section, the RMS error is written in the form of IGA. In section 4, several examples are presented to verify the effectiveness of the developed beam element and its application in the RMS error analysis of antenna reflector. Finally, concluding remarks are given in section 5.

2 Surface Error Estimation

The impact of antenna surface errors on antenna gains can be derived from the Ruze equation [35], the reflector aperture efficiency is multiplied by an exponential factor

where η s is an efficiency factor known as surface tolerance efficiency, G 0 is the gain of the antenna in the absence of surface errors, G is that of the deformed surface, ε rms is the surface error, or RMS half-path-length error, λ is the wavelength.

As shown in Fig. 1, the efficiency factor decreases rapidly with the increase of the surface error, and the aperture efficiency η s =54.1% when ε rms=λ/16.

As a result, severe surface accuracy is demanded by the microwave antennas which work on the wavelength between 3 to 150 mm. The half-path-length errors are obtained from the geometrical deviations between the actual and ideal surfaces

where subscript i denotes the arbitrary point i on the surface, r i denotes the radius of ith point on the reflector, f the focus length, and Δ i is the normal deviation:

where the unkowns u A, v A, w A, h, φ x , φ y are the parameters of the best-fit surface, u i , v i , w i denote the distortion of ith point (x i , y i , z i ) on the reflector. The RMS error can be written as

where A is the area of the aperture. For a FEA model, the equation can be rewritten as

subscript i here denotes the ith finite element node, and n is the total number of the element nodes.

3 Isogeometric Analysis for Surface Error Analysis

The geometric approximation inherent in the mesh of the traditional FEA can lead to accuracy problems [18], especially for surfaces. As a result, the value of \(\varepsilon_{{\text{rms}}}^{F}\) is notoriously sensitive to geometric discretization. Contrarily, the IGA is geometrically exact no matter how coarse the discretization is by using the functions from the geometry description as basis functions for the analysis. The displacement field of the IGA element e can be described as

where \(R_{e}^{a} \left(\varvec{\xi}\right)\) denotes the basis function of the ath control point of element e, and \(\varvec{u}_{e}^{a}\) denotes the displacement of the control point. Fig. 2. shows the IGA element as knot spans, where the red lines denote the knot spans and the black dots the control points of element e.

Unlike the Lagrange elements, the IGA elements are taken to be knot spans, namely, [ξ i−1, ξ i ] × [η i−1, η i ], and the control points are not always located in the element.

3.1 Element formulation for NURBS-based IGA

Shell and beam elements are required for the surface error analysis of the antenna reflector. A brief introduction of the rotation-free Kirchhoff-Love shell element based on NURBS is presented in this section. In addition, a Euler-Bernoulli beam element of three degrees of freedom based on Bézier extraction, which maps the Bernstein polynomial basis on Bézier elements to the NURBS basis, is developed.

3.1.1 Kirchhoff-Love Shell element

Kirchhoff-Love shell based on NURBS has been presented by KIENDL, et al [28]. The variation of the internal work formula of Kirchhoff-Love theory

where C αβγδ denotes the elasticity tensor, ε αβ denotes the membrane strain, κ αβ denotes the bending strain, \(\bar{\varvec{a}}_{\alpha }\) denotes the basis vector of middle surface in the reference configuration, u is the displacement of middle surface, and the subscript ‘,α’ denotes the derivative with respect to ξ α, α=1, 2.

The stiffness matrix of the thin-shell element can be written as

where F is the transformation matrix which links the reference configuration to the deformed configuration, \(\varvec{D}_{e}^{m}\) and \(\varvec{D}_{e}^{b}\) denote the matrix for membrane and bending strains respectively, for details we refer the reader to BEER, et al [36].

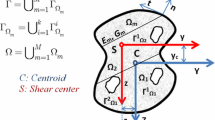

3.1.2 Euler-Bernoulli Beam element

For a 3D beam suffered several different loads, there is additionally the assumption that the beam behaves elastically for the combined loads, as well as for the individual loads, and the deflection is small. In this case, the deflection at any point on the beam is simply the sum of the deflections caused by each of the individual loads. We developed an IGA beam loaded in such a manner that the resultant force passes through the longitudinal shear center axis, i.e. no torsion will occur.

As shown in Fig. 3, each node has five parameters {u, v,

w, θ y , θ z }, where the slope θ can be eliminated by adopting standard structural-mechanics notations

where the prime symbol (•)′ indicates a derivative with respect to x. The geometric equations of strains can be written as

where ε 1 is the tensile strain and the others bending strains. The variation of the internal work formula of the beam can be obtained by using the superposition method

where E denotes the Young’s modulus, A the cross-sectional area, I y and I z the second moment of inertia. Substituting Eq. 6 into the internal work formula, we can obtain the stiffness matrix K in the local coordinates

The NURBS domain can be rewritten in terms of the Bernstein basis by extracting the linear operator which maps the Bernstein polynomial basis on Bézier elements to the NURBS basis

where C e denotes the Bézier extraction operator of element e [37], ξ = (ξ, η) the parametric coordinates defined over the interval [−1, 1], B(ξ) the Bernstein polynomial basis, \(\bar{\varvec{w}}\) and w e are two expressions for the weights of control points

Additionally, transformation of coordinates to a common global system, which will be denoted by \(\bar{x}\bar{y}\bar{z}\) with the local system xyz, will be necessary to assemble the elements. For an element contains n control points, a transformation matrix T e is given to transform the forces and displacements from the global to the local system

with λ being a 3×3 matrix of direction cosines between the two sets of axes

Apparently, T e is an orthogonal matrix which permits the stiffness matrix of an element in the global coordinates to be computed as

3.2 Strong Coupling of the Elements

Two cases of coupling, “beam to beam” and “beam to shell”, are discussed in this section. Due to the endpoint interpolation, i.e. C(−1) = P 1, C(1) = P n , of the beam curves based on NURBS and the coincide exactly with curvature between the beam curve and the connected reflector surface shell, the strong coupling method is suitable for the IGA-based surface error analysis.

3.2.1 Beam to beam coupling

Beams join to each other with a C 0-continuous connection, the angle α between the beams is assumed unchangeable in the deformed configuration.

As shown in Fig. 4, \(P_{i}^{\gamma }\) denotes the ith control point of γth beam. The angle can be described by using the scalar product formula

KIENDL, et al [38], proposed a bending strip method in which strips of fictitious material with unidirectional bending stiffness and zero membrane stiffness are added at patch interfaces to maintain the angle constraint. The method is efficient, simple to implement, and is applied to the coupling of “beam to beam” in this paper.

3.2.2 Beam to shell coupling

There are mainly two types of the “beam to shell” connection in geometrically, intersection and tangency, as shown in Fig. 5. The latter one is the only type used in the surface error analysis.

As shown in Fig. 6, the beam curve is equivalent to a curve on the surface shell, it’s convenient to make the control points of the beam curve coincident with that of the shell by modifying the surface. The constraint function can be described as

where the superscript C and S denote the displacement of the ath point of beam curve and surface respectively.

3.3 RMS error analysis based on IGA shells

The IGA shell element is geometrically exact while the

Langrage element is an approximation of the geometry as shown in Fig. 7, the red dots denote the nodes of the Langrage element. As a result, only the nodes are available to calculate the RMS error as described in Eq. 5 since the point G L in the element have inherent discretization errors. The point G I in the IGA shell element, however, is considered the exact point on the surface. Thus, the arbitrary point in the IGA element is available for the calculation of the RMS error following the Eq. 4.

The four vertices of the IGA shell element, i.e. ξ = (−1, 1), (−1, 1), (1, −1), (1, 1), are adopted to determine the unknowns of the best-fit surface by the least square method. The normal deviation of the arbitrary point on the surface can be written as

The RMS error can then be described as

The Gauss quadrature is adopted to solve the equation

where \({\kern 1pt} Q^{e} \left( {\varvec{\xi}_{j} } \right) = \frac{{\left[ {Y\left( {u_{i}^{e} \left( {\varvec{\xi}_{j} } \right),v_{i}^{e} \left( {\varvec{\xi}_{j} } \right),w_{i}^{e} \left( {\varvec{\xi}_{j} } \right)} \right)} \right]^{2} }}{{1 + \left( {\frac{{r_{i}^{e} \left( {\varvec{\xi}_{j} } \right)}}{2f}} \right)^{2} }},\)

κ j is the weight of the gauss point. The equation is similar with Eq. 5, but however they are different in essence.

4 Numerical Examples

In the following, two numerical examples are presented to reveal the overall performance of the three dimensional Euler-Bernoulli Beam IGA element and the application of IGA in RMS error analysis. First, a Cantilever beam subjected to a point force is introduced to verify the accuracy of the beam element with the analytical solution. And then a parabolic antenna modeled by the Kirchhoff-Love shell and Euler-Bernoulli Beam IGA element is prepared for the RMS error analysis.

4.1 Cantilever beam

The Cantilever beam is subjected to a point force of F = (1, 1, 1)T on the right end point, and is fixed on the left end point, as shown in Fig. 8. The problem is often used as a benchmark to verify the accuracy of the developed beam element.

In our calculations, the geometric and material parameters are assumed as follows: the length L=10; the thickness t=1; the width b=2; the Young’s modulus E=100. The analytical solution can be obtained from

where A = bt, I y = t 3 b/12, I z = b 3 t/12. The cantilever beam is then discretized by 16 IGA Euler-Bernoulli beam elements as shown in Fig. 9, the blue dots denote the control points. For a cubic basis function, each element contains 4 control points (The red diamonds denote the control points of element 1 and the red squares the control points of element 9).

The results comparisons between analytical solutions and IGA solutions are shown in Fig. 10. The maximum relative errors δ of the deformation in the three directions are less than 0.1%, which means the IGA beam element exhibits a high accuracy.

4.2 Surface error analysis of a reflector antenna

The IGA shell and beam elements are now applied to the RMS error analysis of the reflector. In this analysis the antenna is subjected to a gravity load and a wind load corresponding to c = 20 m/s wind at a working angle of 45 degrees, as shown in Fig. 11.

The assembly is composed of a main reflector and a bracket, and is discretized by the IGA shell and beam elements respectively. The “beam to shell” method is applied to couple the reflector surface and the bracket while the “beam to beam” method is applied to couple the beams of the bracket. Three types of beam are adopted to construct the bracket as shown in Fig. 12.

The IGA model and traditional finite element model are shown in Fig. 13.

As listed in Table 1, NURBS-based IGA and traditional FEA are employed in convergence analysis by calculating the max displacement and the RMS error of the model with a different number of control points or nodes under the gravity and wind load. Here, N denotes the number of control points in IGA and nodes in ANSYS. It is clear that the IGA approach rapidly converges at about N=4124 while the traditional FEA simulation reaches the same convergence value until the nodes increase to 23767 both for the value of the maximum displacement and RMS error. The deformation result of IGA is presented in Fig. 14. The surface distortion along the radius of the reflector at the angle of 0° and 90° are presented in Fig. 15.

5 Conclusions

-

(1)

A new IGA beam element is developed by integrating the displacement field of the element, which is approximated by the NURBS basis, with the internal work formula of Euler-Bernoulli beam theory with the small deformation and elastic assumptions.

-

(2)

Two cases of coupling, “beam to beam” and “beam to shell”, are discussed. Due to the endpoint interpolation of the beam curves based on NURBS and the coincide exactly with curvature between the beam curve and the connected reflector surface shell, the strong coupling method is suitable for the IGA-based surface error analysis.

-

(3)

Due to the geometrically exact no matter how coarse the discretization is and the higher-order basis functions, the IGA method is able to achieve the accurate solution with less degrees of freedom than traditional FEA and the arbitrary point in the IGA element is available for the calculation of the RMS error.

-

(4)

The cantilever beam benchmark problem was chosen to demonstrate the good performance of the developed IGA beam element. The maximum relative errors of the deformation in the three directions between analytical solutions and IGA solutions are less than 0.1%.

-

(5)

An antenna model, which is composed of a main reflector and a bracket, is discretized by the IGA shell and beam elements respectively. By coupling the elements strongly, the IGA method is applied in the functional surface error analysis of the antenna reflector successfully. It is clear that the IGA approach reaches the convergence precision with much less control points than traditional FEA.

References

UKITA N, EZAWA H, IKENOUE B, et al. Thermal and wind effects on the azimuth axis tilt of the ASTE 10-m antenna[J]. Publ. Natl. Astron. Obs. Japan, 2007, 10: 25–33.

XIA Xintao, WANG Zhongyu. Grey relation between nonlinear characteristic and dynamic uncertainty of rolling bearing friction torque[J]. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2009, 22(2): 244–249.

LIU Zhenyu, TAN Jianrong, DUAN Guifang, et al. Force feedback coupling with dynamics for physical simulation of product assembly and operation performance[J]. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2015, 28(1): 161–172.

YI Wei, JIANG Zhaoliang, SHAO Weixian, et al. Error compensation of thin plate-shape part with prebending method in face milling[J]. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 2015, 28(1): 88–95.

WANG M, WANG W, WANG C S, et al. A practical approach to evaluate the effects of machining errors on the electrical performance of reflector antennas based on paneled forms[J]. IEEE Antennas & Wireless Propagation Letters, 2014, 13(13): 1341–1344.

ROY L. Structural engineering of microwave antennas: for electrical, mechanical and civil engineers[M]. 1th edition. New York: I.E.E.E. Press, 1996.

TANAKA H. Surface error estimation and correction of a space antenna based on antenna gain analyses[J]. Acta Astronautica, 2011, 68(7): 1062–1069.

XIE Y M, SHI H, ALLEYNE A, et al. Feedback shape control for deployable mesh reflectors using gain scheduling method[J]. Acta Astronautica, 2016, 121: 241–255.

SMITH I A. JCMT active surface control system: implementation[J]. Proceeding of SPIE-The International Society for Optical Engineering, 1998, 3351: 190–196.

TANAKA H, NATORI M C. Shape control of space antennas consisting of cable networks[J]. Acta Astronaut, 2004, 55(3): 519–527.

WANG W, DUAN B Y, LI P, et al. Optimal surface adjustment by the error-transformation matrix for a segmented-reflector antenna[J]. IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, 2010, 52(3): 80–87.

LIU K K, YE Q, MENG G X. Surface error diagnosis of large reflector antenna with microwave holography based on active deformation[J]. Electronics Letters, 2016, 52(1): 12–13.

ELDAR Y C, MENDELSON S. Phase retrieval: stability and recovery guarantees[J]. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal., 2014, 36(3): 473–494.

JENNINGS A, MAGREE D, BRIGGS G, et al. Texture-based photogrammetry accuracy on curved surfaces[C]// Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference, Orlando, USA, APRIL 12–15, 2010: 1060–1071.

YOON H-S. An optimal method of shape control for deformable structures with an application to a mechanically reconfigurable reflector antenna[J]. Smart Materials & Structures, 2010, 19(10): 533–536.

YOU B D, WEN J M, ZHAO Y. Nonlinear analysis and vibration suppression control for a rigid–flexible coupling satellite antenna system composed of laminated shell reflector [J]. Acta Astronautica, 2014, 96(1): 269–279.

DU J L, BAO H, CUI C Z. Shape adjustment of cable mesh reflector antennas considering modeling uncertainties[J]. Acta Astronautica, 2014, 97(2): 164–171.

HUGHES T J R, COTTRELL J A, BAZILEVS Y. Isogeometric analysis: CAD, finite elements, NURBS, exact geometry and mesh refinement[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng., 2005, 194: 4135–4195.

COTTRELL J A, REALI A, BAZILEVS Y, et al. Isogeometric analysis of structural vibrations[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2006, 195(41): 5257–5296.

DÖRFEL M R, JÜTTLER B, SIMEON B. Adaptive isogeometric analysis by local h-refinement with T-splines[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2010, 199(5): 264–275.

CHEN L, NGUYEN-THANH N, NGUYEN-XUAN H. Explicit finite deformation analysis of isogeometric membranes[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2014, 277(277): 104–130.

BAZILEVS Y, HSU M C, SCOTT M A. Isogeometric fluid–structure interaction analysis with emphasis on non-matching discretizations, and with application to wind turbines[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2012, 249–252(249): 28–41.

WALL W A, FRENZEL M A, CYRON C. Isogeometric structural shape optimization[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2008, 197(33–40): 2976–2988.

SEO Y-D, KIM H-J, YOUN S-K. Shape optimization and its extension to topological design based on isogeometric analysis[J]. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 2010, 47(11–12): 1618–1640.

HASSANI B, KHANZADI M, TAVAKKOLI S M. An isogeometrical approach to structural topology optimization by optimality criteria[J]. Struct Multidisc Optim., 2012, 45(2): 223–233.

TAVAKKOLI S M, HASSANI B. Isogeometric topology optimization by using optimality criteria and implicit function[J]. Int. J. Optim. Civil Eng., 2014, 4(2): 151–163.

BUFFA A, SANGALLI G, VÁZQUEZ R. Isogeometric methods for computational electromagnetics: B-spline and T-spline discretizations[J]. Journal of Computational Physics, 2014, 257(2): 1291–1320.

KIENDL J, BLETZINGER K-U, LINHARD J, et al. Isogeometric shell analysis with Kirchhoff–Love elements[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2009, 198(49–52): 3902–3914

DORNISCH W, KLINKEL S, SIMEON B. Isogeometric Reissner–Mindlin shell analysis with exactly calculated director vectors[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2013, 253(1): 491–504.

GRECO L, CUOMO M. An implicit G 1 multi patch B-spline interpolation for Kirchhoff–Love space rod[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2014, 269(1): 173–197.

RUESS M, SCHILLINGER D, ÖZCAN A I, et al. Weak coupling for isogeometric analysis of non-matching and trimmed multi-patch geometries[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2014, 269(2): 46–71.

GUO Y, RUESS M. Nitsche’s method for a coupling of isogeometric thin shells and blended shell structures[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2015, 284: 881–905.

WANG D, XUAN J. An improved NURBS-based isogeometric analysis with enhanced treatment of essential boundary conditions[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2010, 199(37–40): 2425–2436.

EMBAR A, DOLBOW J, HARARI I. Imposing dirichlet boundary conditions with nitsche’s method and spline-based finite elements[J]. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng., 2010, 83(7):877–898.

RUZE J. Antenna tolerance theory-A review[J]. Proc. IEEE., 1996, 54(4): 633–640.

BEER G, BORDAS S. Isogeometric methods for numerical simulation[M]. Springer Vienna, 2015.

BORDEN M J, SCOTT M A, EVANS J A, et al. Isogeometric finite element data structures based on Bézier extraction of NURBS[J]. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Engng., 2011, 87: 15–47.

KIENDL J, BAZILEVS Y, HSU M-C, et al. The bending strip method for isogeometric analysis of Kirchhoff–Love shell structures comprised of multiple patches[J]. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg., 2010, 199(37–40): 2403–2416.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51490663, 51475418, 51521064), and Zhejiang Provincal Key Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017C01045).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

YUAN, P., LIU, Z. & TAN, J. Shape Error Analysis of Functional Surface Based on Isogeometrical Approach. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 30, 544–552 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10033-017-0131-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10033-017-0131-3