Abstract

To evaluate and compare the factor structure and reliability of EPDS and PHQ in antepartum and postpartum samples. Parallel analysis and exploratory factor analysis were conducted to determine the structure of both scales in the entire sample as well as in the antepartum and postpartum groups. McDonald’s omega statistics examined the utility of treating items as a single scale versus multiple factors. Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) was utilized to test the measurement invariance between the antepartum and postpartum groups. Two-factor models fit best for the EPDS in both the antepartum and postpartum groups; however, the most reliable score variance was attributable to a general factor for each scale. MCFA provided evidence of weak invariance across groups regarding factor loadings and partial invariance regarding item thresholds. PHQ-9 showed a two-factor model in the antepartum group; however, the same model did not fit well in the postpartum group. EPDS should be preferred to PHQ-9 for measuring depressive symptoms in peripartum populations. Both scales should be used as a single-factor scale. Caution is required when comparing the antepartum and postpartum scores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perinatal depression is a unipolar, non-psychotic depressive disorder (Howard et al. 2014) characterized by specific feelings and thoughts about the parental role (Langan & Goodbred 2016). It is one of the leading complications for people during pregnancy (antepartum depression) or following childbirth (postpartum depression) (Howard et al. 2014; Howard & Khalifeh 2020). Recent meta-analyses of maternal depression observed a pooled prevalence of 15% and 14%, respectively, for pre- and postnatal depression (Liu Wang & Wang 2022; Yin et al. 2021).

Both new-onset and preexisting depression in pregnant or postpartum people are associated with increased maternal mortality, suicide, and self-harm, as well as adverse obstetrical, neonatal, and long-term outcomes for children (Howard & Khalifeh 2020). All of these consequences lead to substantially increased costs for healthcare systems (Knapp & Wong 2020; Luca et al. 2020). However, growing evidence has identified early screening and prompt management as crucial factors in reducing symptoms and preventing relapses in perinatal people and their families (Austin et al. 2017; O’Connor et al. 2019; Cena et al. 2021).

In line with the World Health Organization’s (2020) recommendations, routine screening for perinatal depression through valid, reliable, and economical screening tools is probably the most widely accepted suggestion (Accortt & Wong 2017; ACOG Committee 2018). However, a consensus has not been reached on what scale can be considered the gold standard. The most frequently validated and utilized screening tools are the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Sambrook Smith et al. 2022a,b). Differently from BDI, both the EPDS and PHQ-9 are free to use as public domain measures.

On a theoretical level, a well-developed and validated disease-specific questionnaire should measure the same construct across different settings and patient populations. Based on this premise and given the clinical and research needs, the PHQ-9 and EPDS are widely used to evaluate levels of depressive symptomatology in both pregnant and postpartum people, examine their developmental trajectories, and compare the results among different groups. However, previous studies have found inconsistent factor structures for both the PHQ-9 and EPDS depending on the perinatal period (i.e., antepartum versus postpartum), ranging from one-factor (e.g., Berle et al. 2003; Woldetensay et al. 2018) to three-factor solutions (e.g., Marcos-Nájera et al. 2018; Matsumura et al. 2020). It should be noted that very few studies have investigated the factor structure of the PHQ-9 with pregnant people and, as far as we know, no study has investigated it in a postpartum sample or tested the measurement invariance of this measure across the perinatal period. Furthermore, regarding the Italian version of both of these two scales, only the EPDS was validated in a perinatal sample (more specifically, a postpartum sample).

Therefore, the aim of the present study is to evaluate and compare the factor structure and reliability of both the EPDS and the PHQ in antepartum versus postpartum samples and test for measurement invariance across the perinatal period.

Methods

Study design and sample

The data presented here were collected as baseline data for a longitudinal study (March 2017–June 2018) on screening and early intervention for maternal perinatal anxiety and depressive disorders. Eleven publicly funded primary or obstetrics-gynecology secondary care centers located throughout Italy were involved in the study as recruitment sites. The inclusion criteria were being pregnant regardless of the trimester of pregnancy (antepartum group) or having a biological newborn aged ≤6 months (postpartum group), and being able to speak and read Italian. The exclusion criteria were having issues with drug or substance misuse and/or having ongoing psychotic symptoms. All participants signed informed consent forms after being provided oral and written explanations of the aims and protocol of this study. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Ethical Committee of the Healthcare Centre of Bologna Hospital. The rationale and full methodology of the larger study have been described in the study protocol (Cena et al. 2020).

Data collection

Each participant was interviewed in a private room inside the healthcare center by a clinical psychologist trained in perinatal clinical psychology and associated with the healthcare center. The aim of the interview was to gather information on the participants’ current and past psychiatric conditions and the use of psychotropic drugs, as well as their current experience with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression. At the end of that interview session, all participants completed the EPDS and PHQ-9 themselves as self-audit. Information on the demographic, economic, and psychosocial as well as reproductive characteristics of participants was collected.

Measures

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

The EPDS (Cox et al. 1987) is the most widely used self-administered instrument to screen for perinatal depression (Sambrook Smith et al. 2022a,b). It can be used to assess depression according to the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) criteria (Smith-Nielsen et al. 2018). The EPDS was originally designed to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in new mothers and was subsequently used to screen for antepartum depression. It assesses the frequency of each of the following depressive symptoms as experienced in the previous 7 days: anhedonia (two items), guilt, anxiety, panic attack, feeling overwhelmed, sleep disturbance, sadness, tearfulness, and suicidal thoughts. The validated Italian translation of the EPDS showed a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.79 and a Guttman split-half coefficient of 0.81 (Benvenuti et al. 1999).

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

The PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al. 2001) is a self-administered depression screening scale containing nine items corresponding to the DSM-IV (Association American Psychiatric 1994) criteria for depression. Furthermore, it can measure depression severity based on the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) criteria (Spitzer et al. 2014). The PHQ-9 is the most widely used depression measure across clinical practice settings worldwide (Hirschtritt & Kroenke 2017; Kroenke 2021) and has been identified as the most reliable depression screening tool (El-Den et al. 2018; Negeri et al. 2021). It assesses the frequency of each of the following depressive symptoms as experienced in the previous 2 weeks: anhedonia, depressed mood, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue or loss of energy, appetite disturbances, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, diminished ability to think or concentrate, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and suicidal thoughts. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the PHQ-9 administered to an obstetric−gynecology sample was 0.86 (Kroenke et al. 2001). The Italian translation of the PHQ-9 showed sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive values of 39, 29, and 93%, respectively, for any depressive syndrome (Mazzotti et al. 2003).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed for each variable, including means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Parallel analysis using the R package EFAtools v0.4.1 (Steiner & Grieder 2020) was performed on a polychoric correlation matrix using the mean eigenvalues and 95th percentile eigenvalues of 5,000 simulated random datasets. The factor structures of both the EPDS and PHQ-9 were explored separately through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the R packages EFAtools v0.4.1 (Steiner & Grieder 2020) and lavaan v0.6-11 (Rosseel, 2012). First, parallel analysis evaluated the number of factors that may be supported by the data in the entire sample as well as in the antepartum and postpartum subgroups by comparing actual eigenvalues to random eigenvalues sampled at the 95th percentile (Glorfeld 1995). Scree plots were also examined. The scree plot and eigenvalues associated with each factor were also used to identify the number of meaningful factors. Next, a series of EFA models with maximum likelihood extraction and oblique rotation was performed to evaluate item loadings. These analyses were repeated three times, setting the extracted number of the factors to three, two, and one given the results of parallel analyses and also because no studies indicated structures of four or more factors for both the EPDS and PHQ-9 (for a review of various factor models of the EPDS see Matsumura et al. 2020; for the PHQ-9 see Barthel et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2022a,b; and Marcos-Nájera et al. 2018). Factor loadings ≥ 0.32 were used in the factor designation (Tabachnick & Fidell 2019). Next, the model with the best fit was tested by the multiple-group CFA method in order to assess measurement invariance between pre- and postnatal groups. A well-fitting baseline model was established, and the effects of equality constraints across groups were evaluated by likelihood ratio tests. Evidence for reasonably good fit was assessed using standard fit indices, including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; values close to 0.06 or below are considered good) and comparative fit index (CFI; close to 0.95 or greater). All tests were two-tailed, with the statistical significance level set at α = 0.05. Lastly, omega reliability coefficients were calculated using the R package Psych v2.2.9 (Revelle 2022). Omega total measures the total reliable variance for each scale, and omega hierarchical indexes the variance attributable to a single general factor. High values of omega total indicate an overall reliable scale, and high omega hierarchical values support interpreting item scores as a single scale.

All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.2.0 (R Core Team 2022).

Results

Sample characteristics

Approximately 30% of the subjects approached refused to participate in the study, and n = 1 subject was not eligible to participate due to ongoing psychotic symptoms. No participants dropped out during the baseline evaluation. The overall sample included 1477 people: 1166 pregnant people and 311 new mothers. The two groups did not differ in nationality, marital status, educational level, working status, economic status, having planned the pregnancy or not, resorting to assisted reproductive technology or not, and history of past abortions. Compared to pregnant people, new mothers were older (p < 0.01), were more likely to have previous pregnancies (p < 0.01), and had children living at the time of this pregnancy/birth (p < 0.01). The sociodemographic and reproductive information are shown in Table 1.

Parallel analysis

The number of factors identified by the parallel analyses with principal component analysis (PCA), exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and squared multiple correlation (SMC) was as follows: EPDS whole group: one, five, and six; EPDS antepartum group: two, six, and six; EPDS postpartum group: one, four, and NA; PHQ-9 whole group: one, three, and four; PHQ-9 antepartum group: two, four, and five; PHQ-9 postpartum group: one, five, and six.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

For both the EPDS and PHQ-9, we ran EFAs comparing the two models suggested by parallel analyses (i.e., two-factor and three-factor models) using the entire sample, the antepartum sample, and the postpartum sample (see Table 2).

Regarding EPDS, eigenvalues and percentage cumulative variance were as follows: 3.74 (37.4%) and 1.94 (56.8.0%) for the entire sample’s two-factor solution; 3.36 (33.5%) and 1.87 (52.2%) for the antepartum group’s two-factor solution; 3.01 (30.9%) and 2.10 (51.9%) for the postpartum group’s two-factor solution; 3.17 (31.7%), 1.73 (49.0%), and 2.16 (60.6%) for the entire sample’s three-factor solution; 2.17 (21.7%), 1.81 (38.8%), and 1.73 (56.1%) for the antepartum group’s three-factor solution; lastly, EFA could not be estimated for the postpartum group’s three-factor model. Item 6 does not load on any of the extracted factors within the antepartum group.

Regarding the PHQ-9, eigenvalues and percentage cumulative variance were as follows: 3.29 (36.5%) and 1.62 (56.4%) for the entire sample’s two-factor solution; 3.10 (34.4%) and 1.61 (52.3%) for the antepartum group’s two-factor solution; 3.60 (40.0%) and 3.15 (75.0%) for the postpartum group’s two-factor solution; 2.71 (30.1%), 1.41 (45.7%), and 1.29 (60.0%) for the entire sample’s three-factor solution; 2.72 (30.2%), 1.48 (46.6%), and 1.20 (59.9%) for the antepartum group’s three-factor solution; 2.63 (29.2%), 2.24 (54.1%), and 1.28 (68.2%) for the postpartum group’s three-factor solution.

Table 3 presents CFA fit indices for the two- and three-factor models of the EPDS and PHQ-9 in the entire sample as well as the pre- and postpartum groups reported in Table 3.

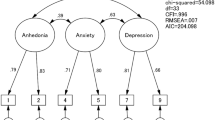

Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Table 4 shows fit statistics for multigroup confirmatory models with increasingly stringent equality constraints. Chi-squared difference tests are shown comparing each model to the one in the row above. For identification, the first item of each factor was set to 1 in each group. For the EPDS, baseline model parameters freely estimated for each group demonstrated acceptable fit [X2(68) = 196.306, CFI = .993, RMSEA = .051, SRMR = .056]. Constraining the free loadings to equality across groups did not significantly harm model fit (p = .58). Imposing further constraints on the estimated item thresholds did yield a significantly worse fitting model based on the chi-squared test (p < .001); however, overall fit based on other indices was still in the acceptable range (CFI = .989, RMSEA = .051, SRMR = .057). Similarly, for the PHQ-9, a baseline model showed acceptable overall fit [X2(52) = 181.023, CFI = .983, RMSEA = .058, SRMR = .076], and constraining loadings to equality across perinatal groups did not significantly worsen the fit (p = .12). Further constraining item thresholds to equality did significantly harm model fit compared to baseline (p < .001); however, other fit indices remained within acceptable limits. Thus, both the EPDS and PHQ-9 demonstrated evidence of at least weak measurement invariance across perinatal groups using the two-factor models.

Reliability

Both scales performed similarly across measures of reliability and internal consistency, though the EPDS showed slightly higher ratings across all metrics. Scores on both scales had adequate alphas (.80 and .84 for PHQ-9 and EPDS, respectively) and similarly high overall reliable variance (omega total) based on a two-factor hierarchical model (Revelle & Condon 2019). Compared to the PHQ-9, the EPDS showed higher omega hierarchical (.67 versus .57). Finally, the average inter-item correlation was higher for the EPDS Table 5.

Discussion

Comparison with previous studies

The results presented in this study supported a two-factor solution for both scales across perinatal samples. However, while the EPDS performs well in both the antepartum and postpartum groups in terms of factor model fit and reliability (alpha, omega, and average item correlation), the PHQ-9 shows adequate performance only in the antenatal group and has inconsistent factor loadings and poor model fit in the postpartum group. Therefore, our findings indicate that the PHQ-9 may not be well-adapted for measuring depressive symptoms in the postpartum Italian-speaking population and that the EPDS should be preferred. For both scales, however, caution is required when comparing antepartum to postpartum scores, as discussed below. Lastly, given that the general factor heavily saturates the individual factors in both scales, the EPDS and PHQ-9 should probably be used as single-factor scales.

The two-factor structure model of the EPDS was consistently observed in the whole sample (without using residual covariances) as well as separately in the antepartum and postpartum samples. The two factors detected were related to depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively. Invariance testing revealed that loadings can be equated across antepartum and postpartum but not the thresholds. This suggests that although the EPDS items are related to the construct of depressive symptomatology in a similar way, one should take caution in interpreting mean differences across antepartum and postpartum groups. On a practical level, this means that a score of X at prepartum does not necessarily indicate the same level of depressive symptoms as a score of X at postpartum, but a change of ±Y points likely indicates the same change in both groups.

Our results concerning the factor structure of the EPDS are in line with the only previous Italian study on the topic (Della Vedova et al. 2022). However, they are inconsistent with most of the international literature which has found a three-factor solution (e.g., Coates et al. 2017; Kubota et al. 2018; Long et al. 2020). Differences in factor number and composition may plausibly depend on differences in cultural and/or language features. In fact, culturally sensitive cut-off values for the EPDS have been recommended, and they vary considerably, ranging from nine to fourteen for different populations (Halbreich & Karkun 2006; Smith-Nielsen et al. 2018). Such differences are likely owing to cultural variations in the attributions and expressions of depressive symptoms and the language used to describe them (Haroz et al. 2017; Lara-Cinisomo et al. 2020).

Regarding PHQ-9, our findings suggest a two-factor structure model in the antenatal group. Unlike the EPDS, only very few studies have thus far investigated the factor structure of the PHQ-9 in perinatal samples. Different factor structures were found during the antepartum period, and it seems plausible that these differences stem from cultural differences. Two studies involving Peruvian pregnant women agreed on indicating the same two-factor solution with the same items assigned to each scale (Smith et al. 2022a,b; Zhong et al. 2014). Similarly, a Japanese study found a two-factor model but with different assignments of items to scales (Wakamatsu et al. 2021). Further two studies involving Ethiopian versus Ivorian and Ghanaian pregnant women suggested a one-factor structure (Barthel et al. 2015; Woldetensay et al. 2018). Finally, a three-factor model (cognitive-affective, somatic, and pregnancy-related) was considered adequate to screen depression in Spanish pregnant women (Marcos-Nájera et al. 2018). To our knowledge, no studies except ours have examined the factor structure of the PHQ-9 in postpartum samples.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis on screening for perinatal depression identified 15 studies providing psychometric comparisons between the EPDS and PHQ-9 and found that their operating characteristics of sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve were remarkably similar (Wang et al. 2021). However, this study focused on the diagnostic accuracy of these scales rather than their psychometric properties. The present study offers important new evidence about the measurement invariance of these scales across the perinatal period which can inform the choice of which scale to use in clinical practice and research.

The different performances observed between the PHQ-9 and EPDS, especially in the postpartum group, support a possible partial explanation that they capture partially distinct features of depressive symptomatology. In fact, growing evidence indicates that genetic etiologies for perinatal depression overlap only partially with those for non-perinatal depression (Viktorin et al. 2016) and that there exist different types and severities of perinatal depression (Putnam et al. 2017). Only depression occurring in the later postpartum period (i.e., after the 8th week postpartum) seems to be more similar to a major depressive disorder occurring outside of the perinatal period (Batt et al. 2020). It is therefore possible that the main differences are likely related to the specific development of the two scales. The EPDS was specifically devised for postpartum depression using items drawn from three scales for anxiety and depression [i.e., the Irritability, Depression, and Anxiety Scale (Snaith et al. 1978), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond & Snaith 1983), and the Anxiety and Depression Scale (Bedford et al. 1976)], and deemphasizing the somatic symptoms that might overlap with depressive symptoms even when they should be considered normative during postpartum. The PHQ-9 was instead developed specifically to identify depressive disorders based on DSM-IV criteria and was derived from the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD; Spitzer et al. 1994), which was originally devised to identify mood, anxiety, somatoform, alcohol, and eating disorders in the general population. As a result, in both scales, some items are not entirely consistent with the depressive dimension; the PHQ-9 includes items addressing somatic symptoms, whereas the EPDS includes items addressing anxiety. This is a key difference because, on the one hand, somatic symptoms are strongly experienced by perinatal women, even if they are not clinically depressed (Pereira et al. 2014), and the presence of somatic symptoms during antenatal depression predicts postpartum depressive symptoms even if these symptoms have subsided (Roomruangwong et al. 2017). On the other hand, besides depressive symptoms, anxiety is the most common psychological symptom observed in both pregnant people and new mothers (Cena et al. 2020; Cena et al. 2021a, 2021b; Nakić Radoš et al. 2018).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the present study include the use of a large perinatal sample and several clinical centers located throughout Italy. Furthermore, this study used multigroup confirmatory factor analysis to assess measurement invariance across the perinatal period—the first paper that we know of to apply this modern psychometric approach to compare the EPDS and PHQ-9. Finally, this is the first study to examine the factor structure of the Italian version of the EPDS in an antepartum sample, as well as the first to examine the factor structure of the Italian version of the PHQ-9 in a perinatal sample. However, there are also some noteworthy limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design precludes the evaluation of the test-retest reliability of the scales. Another limitation regards the fact that the factor structure of both the EPDS and the PHQ-9 across trimesters was not examined. Lastly, because our sample population was entirely composed of people living in Italy, it may not be representative of other country populations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in the present study, the Italian version of the EPDS demonstrated reliability but weak (i.e., factor loadings equated) measurement invariance across antepartum and postpartum groups. In contrast, the Italian version of the PHQ-9 showed adequate performance with pregnant people but had inconsistent factor loadings and poor model fit with postpartum people. Therefore, we conclude that the EPDS should be preferred to the PHQ-9 for measuring depressive symptoms in the perinatal population but should be used with caution when comparing antepartum to postpartum scores. Lastly, we recommend that both the EPDS and PHQ-9 can be used as a single-factor scale.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Accortt EE, Wong MS (2017) It is time for routine screening for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in obstetrics and gynecology settings. Obstet Gynecol Surv 72:553–568. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0000000000000477

ACOG Committee (2018) Opinion No. 757: Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol 132(5):e208–e212. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002927

American Psychiatric Association (2013) The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (4th edn text revision)(DSM-IVTR). American Psychiatric Publishing

Association American Psychiatric (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition text revision (DSM-IV- TR). American Psychiatric Publishing

Austin M-P, Highet N, The Expert Working Group (2017) Mental health care in the perinatal period: Australian clinical practice guideline. Centre of Perinatal Excellence

Barthel D, Barkmann C, Ehrhardt S, Schoppen S, Bindt C, International CDS Study Group (2015) Screening for depression in pregnant women from Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana: psychometric properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. J Affective Disord 187:232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.042

Batt MM, Duffy KA, Novick AM, Metcalf CA, Epperson CN (2020) Is postpartum depression different from depression occurring outside of the perinatal period? A review of the evidence. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing) 18(2):106–119. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20190045

Bedford A, Foulds GA, Sheffield BF (1976) A new personal disturbance scale (DSSI/sAD). Br J Soc Clin Psychol 15:387–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1976.tb00050.x

Benvenuti P, Ferrara M, Niccolai C, Valoriani V, Cox JL (1999) The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale: validation for an Italian sample. J Affect Disord 53:137–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00102-5

Berle JØ, Aarre TF, Mykletun A, Dahl AA, Holsten F (2003) Screening for postnatal depression validation of the Norwegian version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, and assessment of risk factors for postnatal depression. J Affect Disord 76:151–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00082-4

Cena L, Biban P, Janos J, Lavelli M, Langfus J, Tsai A, Youngstrom EA, Stefana A (2021) The collateral impact of COVID-19 emergency on neonatal intensive care units and family-centered care: challenges and opportunities. Front Psychol 12:630594. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.630594

Cena L, Gigantesco A, Mirabella F, Palumbo G, Camoni L, Trainini A, Stefana A (2021a) Prevalence of comorbid anxiety and depressive symptomatology in the third trimester of pregnancy: analysing its association with sociodemographic, obstetric, and mental health features. J Affective Disord 295:1398–1406

Cena L, Gigantesco A, Mirabella F, Palumbo G, Trainini A, Stefana A (2021b) Prevalence of maternal postnatal anxiety and its association with demographic and socioeconomic factors: a multicentre study in Italy. Front Psychol 12:737666. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.737666

Cena L, Mirabella F, Palumbo G, Gigantesco A, Trainini A, Stefana A (2020) Prevalence of maternal antenatal anxiety and its association with demographic and socioeconomic factors: a multicentre study in Italy. Eur Psychiatry 63:E84. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.82

Cena L, Palumbo G, Mirabella F, Gigantesco A, Stefana A, Trainini A, Tralli N, Imbasciati A (2020) Perspectives on early screening and prompt intervention to identify and treat maternal perinatal mental health. Protocol for a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Front Psychol 11:365. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00365

Coates R, Ayers S, de Visser R (2017) Factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in a population-based sample. Psychol Assess 29:1016–1027. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000397

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry 150:782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

Della Vedova AM, Loscalzo Y, Giannini M, Matthey S (2022) An exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis study of the EPDS in postnatal Italian-speaking women. J Reprod Infant Psychol 40(2):168–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2020.1822993

El-Den S, Chen TF, Gan YL, Wong E, O’Reilly CL (2018) The psychometric properties of depression screening tools in primary healthcare settings: a systematic review. J Affective Disord 225:503–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.060

Glorfeld LW (1995) An improvement on Horn’s parallel analysis methodology for selecting the correct number of factors to retain. Educ Psychol Meas 55(3):377–393. https://doi.org/10/b3fjvm

Halbreich U, Karkun S (2006) Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. J Affective Disord 91(2-3):97–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.051

Haroz, E. E., Ritchey, M., Bass, J. K., Kohrt, B. A., Augustinavicius, J., Michalopoulos, L., ... & Bolton, P. (2017). How is depression experienced around the world? A systematic review of qualitative literature. Soc Sci Med, 183, 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.030

Hirschtritt ME, Kroenke K (2017) Screening for depression. JAMA 318(8):745–746. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.9820

Howard LM, Khalifeh H (2020) Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 19(3):313–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20769

Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis CL, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J (2014) Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet (London, England) 384(9956):1775–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9

Knapp M, Wong G (2020) Economics and mental health: the current scenario. World Psychiatry 19(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20692

Kroenke K (2021) PHQ-9: global uptake of a depression scale. World Psychiatry 20(1):135–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20821

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (2001) The PHQ-9. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16:606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Kubota, C., Inada, T., Nakamura, Y., Shiino, T., Ando, M., Aleksic, B., ... & Ozaki, N. (2018). Stable factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale during the whole peripartum period: results from a Japanese prospective cohort study. Sci Rep, 8(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36101-z

Langan RC, Goodbred AJ (2016) Identification and management of peripartum depression. Am Fam Physician 93(10):852–858

Lara-Cinisomo S, Akinbode TD, Wood J (2020) A systematic review of somatic symptoms in women with depression or depressive symptoms: do race or ethnicity matter? J. Women’s Heal 2019:7975. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.7975

Liu X, Wang S, Wang G (2022) Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs 31:19–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16121

Long, M. M., Cramer, R. J., Bennington, L., Morgan Jr, F. G., Wilkes, C. A., Fontanares, A. J., ... & Paulson, J. F. (2020). Psychometric assessment of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in an obstetric population. Psychiatry Res, 291, 113161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113161

Luca DL, Margiotta C, Staatz C, Garlow E, Christensen A, Zivin K (2020) Financial toll of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders among 2017 births in the United States. Am J Public Health 110(6):888–896. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305619

Marcos-Nájera R, Le HN, Rodríguez-Muñoz MF, Olivares Crespo ME, Izquierdo Mendez N (2018) The structure of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in pregnant women in Spain. Midwifery 62:36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.03.011

Matsumura K, Hamazaki K, Tsuchida A et al (2020) Factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Sci Rep 10:11647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67321-x

Mazzotti, E., Fassone, G., Picardi, A., Sagoni, E., Ramieri, L., Lega, I., ... & Pasquini, P. (2003). II Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) per lo screening dei disturbi psichiatrici: Uno studio di validazione nei confronti della Intervista Clinica Strutturata per il DSM-IV asse I (SCID-I). Ital J Psychopathol, 9(3), 235-242

Nakić Radoš S, Tadinac M, Herman R (2018) Anxiety during pregnancy and postpartum: course, predictors and comorbidity with postpartum depression. Acta Clinica Croatica 57(1):39–51. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2017.56.04.05

Negeri ZF, Levis B, Sun Y, He C, Krishnan A, Wu Y, Bhandari PM, Neupane D, Brehaut E, Benedetti A, Thombs BD, Depression Screening Data (DEPRESSD) PHQ Group (2021) Accuracy of the patient health questionnaire-9 for screening to detect major depression: updated systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 375:n2183. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2183

O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger M, Gaynes BN, Coppola E, Weyrich MS (2019) Interventions to prevent perinatal depression. Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 321:588–601. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.20865

Pereira, A. T., Marques, M., Soares, M. J., Maia, B. R., Bos, S., Valente, J., ... & Macedo, A. (2014). Profile of depressive symptoms in women in the perinatal and outside the perinatal period: similar or not?. J Affective Disord, 166, 71-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.008

Putnam, K. T., Wilcox, M., Robertson-Blackmore, E., Sharkey, K., Bergink, V., Munk-Olsen, T., Deligiannidis, K. M., Payne, J., Altemus, M., Newport, J., Apter, G., Devouche, E., Viktorin, A., Magnusson, P., Penninx, B., Buist, A., Bilszta, J., O'Hara, M., Stuart, S., Brock, R., … Postpartum depression: action towards causes and treatment (PACT) consortium (2017). Clinical phenotypes of perinatal depression and time of symptom onset: analysis of data from an international consortium. Lancet Psychiatry, 4(6), 477–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30136-0

R Core Team (2022) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria URL https://www.r-project.org/

Revelle W (2023) Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/psych.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2023

Revelle W, Condon DM (2019) Reliability from α to ω: a tutorial. Psychol Assess 31(12):1395–1411. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000754

Roomruangwong C, Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Mahieu B, Nowak G, Maes M (2017) Lower serum zinc and higher CRP strongly predict prenatal depression and physio-somatic symptoms, which all together predict postnatal depressive symptoms. Mol Neurobiol 54(2):1500–1512

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48(2):1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Smith ML, Sanchez SE, Rondon M, Gradus JL, Gelaye B (2022b) Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for detecting depression among pregnant women in Lima, Peru. Curr Psychol: J Diverse Perspect Diverse Psychol Issues 41(6):3797–3805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00882-2

Smith MS, Cairns L, Pullen LSW, Opondo C, Fellmeth G, Alderdice F (2022a) Validated tools to identify common mental disorders in the perinatal period: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Affective Disord 298:634–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.011

Smith-Nielsen J, Matthey S, Lange T, Væver MS (2018) Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale against both DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression. BMC Psychiatry 18:393. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1965-7

Snaith RP, Constantopoulos AA, Jardine MY, McGuffin P (1978) A clinical scale for the self-assessment of Irritability. Br J Psychiatry 132:164–171. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.132.2.164

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FV 3rd, Hahn SR, Brody D, Johnson JG (1994) Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 272(22):1749–1756

Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroeneke K (2014) Test review: Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9). Rehabil Couns Bull 57:246–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355213515305

Steiner MD, Grieder S (2020) EFAtools: an R package with fast and flexible implementations of exploratory factor analysis tools. J Open Source Softw 5(53):2521. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.02521

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2019) Using multivariate statistics, 7th edn. Pearson

Viktorin A, Meltzer-Brody S, Kuja-Halkola R, Sullivan PF, Landén M, Lichtenstein P, Magnusson PK (2016) Heritability of perinatal depression and genetic overlap with nonperinatal depression. Am J Psychiatry 173(2):158–165. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010085

Wakamatsu M, Minatani M, Hada A, Kitamura T (2021) The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 among first-trimester pregnant women in Japan: factor structure and measurement and structural invariance between nulliparas and multiparas and across perinatal measurement time points. Open J Depress 10:121–137. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojd.2021.103008

Wang L, Kroenke K, Stump TE, Monahan PO (2021) Screening for perinatal depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 68:74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.12.007

Woldetensay YK, Belachew T, Tesfaye M, Spielman K, Biesalski HK, Kantelhardt EJ et al (2018) Validation of the patient health qQuestionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression in pregnant women: Afaan Oromo version. PLoS ONE 13(2):e0191782. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191782

World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe (2020) Screening programmes: a short guide. Increase effectiveness, maximize benefits and minimize harm. World Health Organization

Yin, X., Sun, N., Jiang, N., Xu, X., Gan, Y., Zhang, J., ... & Gong, Y. (2021). Prevalence and associated factors of antenatal depression: systematic reviews and meta-analyses Clin Psychol Rev, 83, 101932, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101932

Zhong Q, Gelaye B, Rondon M, Sánchez SE, García PJ, Sánchez E, Barrios YV, Simon GE, Henderson DC, Cripe SM, Williams MA (2014) Comparative performance of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for screening antepartum depression. J Affect Disord 162:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.028

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The work of the first author was supported by a Marie Sklodowska-Curie global fellowship from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 101030608).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alberto Stefana: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing the original draft, and writing the review and editing. Joshua A. Langfus: formal analysis, writing the original draft, and writing the review and editing. Gabriella Palumbo: writing the review and editing. Loredana Cena: project administration and writing the review and editing. Alice Trainini: data curation and writing the review and editing. Antonella Gigantesco: supervision and writing the review and editing. Fiorino Mirabella: formal analysis, supervision, and writing the review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Antonella Gigantesco and Fiorino Mirabella contributed to this work and should be considered co-last authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stefana, A., Langfus, J.A., Palumbo, G. et al. Comparing the factor structures and reliabilities of the EPDS and the PHQ-9 for screening antepartum and postpartum depression: a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health 26, 659–668 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01337-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-023-01337-w