Abstract

Background

The objective was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of shunt surgery in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH).

Methods

Health-related quality of life was evaluated before and 6 months after surgery using the EQ-5D-3 L (EuroQOL group five-dimensions health survey) in 30 patients (median age, 71 years; range, 65–89 years) diagnosed with iNPH. The costs associated with shunt surgery were assessed by a detailed survey with interviews and extraction of register data concerning the cost of hospital care, primary care, residential care, home-care service and informal care. The cost of untreated patients was derived from the cost of dementia disorders in Sweden in 2012, as reported by the National Board of Health and Welfare. The cost effectiveness analysis used a decision-analytic Markov model. We used a societal perspective and a lifelong time horizon to estimate costs and effects. One-way sensitivity analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis were carried out to test the robustness of the model.

Results

The shunt surgery model as the standard treatment in iNPH resulted in a gain of 2.2 life years and 1.7 quality-adjusted life years (QALY), along with an incremental cost per patient of €7,500/QALY. The sensitivity analysis showed that the results were not sensitive to changes in uncertain parameters or assumptions.

Conclusions

Shunt surgery in iNPH, an underdiagnosed condition severely impairing elderly patients, is not only an effective medical treatment, it is also cost-effective, adding 2.2 additional life years and 1.7 QALYs at a low cost, a remarkable gain for an individual aged around 70 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) is a treatable gait disorder and one of very few treatable causes of dementia, most often also causing balance and urinary disturbances [25]. Treatment by shunt surgery is effective with substantial clinical improvement in up to 80% of the patients [4, 25, 43]. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is lower in iNPH patients than in age-matched healthy individuals [19, 31], but improves in 86% of patients after surgery to almost the same level as in the normal population [31].

The prevalence of iNPH is high. Between 0.5 and 2.9% of people older than 65 years of age suffer from iNPH [5, 18, 40]. The disorder is underdiagnosed as well as undertreated; possibly only about 20% of affected patients undergo shunt surgery [6, 40, 42].

Taken together with improved diagnostic methods and increased knowledge about the disorder, the number of patients in need of shunt surgery for iNPH will most likely increase. This will challenge the allocation of healthcare resources.

The cost benefit of shunt surgery in iNPH has been addressed in only a few studies. In a retrospective study of patients with hydrocephalus, the Medicare expenditure for treated patients was lower than for untreated patients [41]. Based on data from the literature, the average 65-year-old patient receiving a shunt would gain an additional 1.7 QALYs [36]. The caregiver burden (Zarit burden interview score) also decreases after a shunt operation [22]. Kameda et al. [20] recently reported that shunt surgery yields a positive return on investment within less than 2 years.

The cost effectiveness of treating iNPH has not been investigated in a prospective study with patient experienced QoL and cost data, and the aim of the present study was to investigate this from a societal perspective, using a decision-analytic Markov model adapted to Swedish circumstances.

Methods

Patients

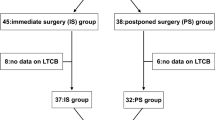

Thirty-seven patients (23 men, 14 women; median age, 70 years; range, 50–89 years), consecutively diagnosed with probable iNPH according to the American-European guidelines [34] at the Hydrocephalus Research Unit, were primarily included. Diagnosis was based on detailed assessment of typical clinical symptoms and signs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings according to the guidelines: no supplementary tests were used for inclusion. A lumbar puncture was performed in all cases, and the intracranial pressure (ICP) was determined (<18 mm Hg in all). The patients and their HRQoL data have been described in detail by Petersen et al. [31]. Seven patients aged <65 years were excluded and data for the remaining 30 retired patients aged ≥65 years were used in the cost-effectiveness analysis (16 men, 14 women; median age, 71; range, 65–89 years). Prior to surgery, the median Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was 24 (range, 15–30), four patients had municipal home help service (cooking, cleaning, purchases, etc.), one was living in residential care, five patients needed help with personal activities of daily living (ADL), and 20 patients needed help with instrumental ADL, as measured by the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) and the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) instruments. All patients had their symptoms and signs scored on the iNPH scale [15] by an experienced neurologist, physiotherapist and neuropsychologist before and at re-evaluation 6 months after surgery. A change in the score (after surgery) of ≥5 points was categorised as improvement and <5 points as a poor outcome.

All patients received a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt with a Codman Hakim programmable valve and an anti-siphon device. All shunts were working at the 6-month postoperative evaluation.

Analysis of cost effectiveness

The Markov model

The cost effectiveness of shunt surgery in iNPH was analysed using a decision-analytic Markov model adapted to a Swedish setting. The Markov model is a mathematical model consisting of different health states that the simulated population can be in and move between [7]. The model was constructed with four health states for the shunt surgery pathway: “Improved”, “Complication”, “Deteriorated” and “Death” (death from iNPH or other causes). For the natural history, the model was constructed with two health states: “Natural history” and “Death” (death from iNPH or other causes) (Fig. 1). The input parameters in the model are presented in Table 1. The model simulated the course of events in a hypothetical cohort of 1,000 patients aged 70 years. The simulation model allowed us to estimate the lifelong costs and effects on HRQoL of performing shunt surgery in hypothetical individuals with iNPH and compare these with individuals who receive no treatment (natural history). The primary outcome of the model was the cost per gained quality-adjusted life year (QALY). QALY combines life years and HRQoL using a single index, often called QALY-weight, between 0 and 1, where 0 equals death and 1 represents perfect health. Thus, 1 QALY corresponds to 1 year of “perfect” health. The analysis had a societal perspective (including both the healthcare cost of hospital care, primary care and residential care and the cost of home-care service and care and support given by relatives). The long-term mortality risk (>1 year) for the state “Improved” was approximately 2.5 times [26, 41] higher than among the general population in Sweden [38]. The same applies to mortality for the states “Deteriorated” and “Natural history” but with an additional 10% risk of mortality [2]. A 3% discount rate was used for costs and effects throughout the model. Both deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were carried out to study the uncertainty of parameters and assumptions. The model was programmed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

QALY-weights

Age-dependent QALY-weights based on the Swedish population were used in the model [9]; hence, the decline in HRQoL for reasons other than iNPH were also considered in the model. The QALY-weights were assessed with the EQ-5D-3 L (EuroQoL group five-dimensions health survey with three levels) [45], which is a generic preference-based measure of health, measured before and 6 months after surgery [31]. The value is based on data generated from a national general public survey using the time-trade-off (TTO) method to elicit mean TTO values at each health state [9]. Since there is no Swedish TTO tariff for the EQ-5D health states, the UK EQ-5D index tariff was used [39].

Costs

A detailed survey was made to assess the cost of the shunt-operated patients 6 months after shunt surgery, used as a source for costs in the Markov model. In this survey, all contacts with the health service and the associated costs were extracted from medical records. All patients were examined and prospectively interviewed personally by an occupational therapist (J.B.), before (at hospital) and 6 months after surgery (at hospital or in their homes). The number of hours per week that the relatives provided practical support and surveillance during their leisure time and the number of hours that the patients had home-care service were recorded and the corresponding costs estimated. The following costs associated with shunt surgery were assessed: (1) cost of healthcare, including hospital inpatient and outpatient visits, shunt surgery, primary care physician visits, contacts with a physiotherapist, occupational therapist or nurse; (2) cost of residential care in nursing home and home-help service costs (formal care); (3) cost of care given by relatives in their spare time (informal care). The annual cost was estimated by an extrapolation of data from the first 6 months shown in Table 1.

After shunt surgery, 7% (2 out of 30) of the patients in this survey lived in residential care, 23% (7 out of 30) received home care and 60% (18 out of 30) received informal support (Table 1). Formal and informal care were valued according to the valuation in the National Board of Health and Welfare report [35]. One hour of home help service was valued at €38 (SEK 378) and the annual cost of living in a nursing home was valued at €62,000 (SEK 606,000). The informal care was valued according to the opportunity cost method [10], where the informal care is valued as the person’s best alternative use of time. Loss of production was valued using the human capital approach [13], assuming that production loss can be valued at market price; i.e. gross salaries and payroll taxes. The opportunity cost of lost leisure time was estimated at 35% of the hourly loss of production of employed relatives [32]. One hour of informal care was valued at €15 (SEK 152), which is weighted to include both the loss of productivity and the loss of leisure time. The cost of the patient’s loss of production was not included, as the data applied to retired patients.

The cost of untreated patients with iNPH (natural history) was derived from the cost of dementia disorders in Sweden in 2012, as reported by the National Board of Health and Welfare [35]. According to this report, 42% lived in residential care and 58% lived in their own home, of whom 6% received day care. For those who lived on their own, it was estimated that the patients received 0.5 h of home care and 1.9 h of informal care per day.

All costs were adjusted according to the inflation rate for prices in 2016 and the exchange rates applicable on 3 November 2016 (Euro from Swedish Kronor and British Pound Sterling).

Sensitivity analysis

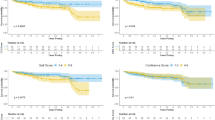

A one-way sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the importance of uncertain parameters and assumptions (i.e. the risk of mortality, cost of municipal residential care and informal support in the cohort with natural history, utility weight of “improved” and “deteriorated”, the discount rate and with a healthcare perspective). A second-order probabilistic sensitivity analysis of the statistical uncertainty of parameters was undertaken using Monte Carlo simulation [8]. These parameters included the probabilities of state transitions, costs and QALYs for 5,000 bootstrap replicates. Since the costs are skewed, gamma distribution was used for the costs in the model. The result was plotted on an incremental cost effectiveness plane (Fig. 2). The willingness-to-pay (WTP) level was set based on current NICE guidelines [30] to £20,000/QALY (€22,150/QALY) for the lower threshold and £30,000/QALY (€33,220/QALY) for the upper threshold.

The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to analyse changes in the iNPH scale score and HRQoL after shunt surgery.

The study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Gothenburg, Sweden. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and/or their relatives.

Results

The lifelong cost-effectiveness model showed that shunt surgery resulted in a gain in both life years saved and QALYs of the simulated cohort, compared with natural history patients (Fig. 3). According to the model, shunt surgery resulted in a gain of 2.2 life years and 1.7 QALYs at an incremental cost of €13,000, compared with natural history. The incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) was €7,500/QALY (Table 2). The incremental cost per life year saved was €6,000.

The estimated annual costs after surgery and for the natural history patients are shown in Table 1.

Sensitivity analysis

The one-way sensitivity analysis showed that the results were not sensitive to major changes in risk of mortality, cost of municipal residential care and cost of informal care for the cohort with the natural history, utility weight for the state “Improved” and “Deteriorated” as well as the discount rate (Table 3). Shunt surgery still generated a low cost per gained QALY. With a healthcare perspective, the cost would be €4,300 per gained QALY. The reliability of the results was also tested with probabilistic analyses. The Monte Carlo simulation exercise indicates robustness of the model: shunt surgery is cost-effective with a probability of 98.5% (lower WTP threshold) and 100% (upper WTP threshold) of the Monte Carlo simulations (Fig. 2).

Patient outcomes

Six months after shunt surgery, 20 (67%) of the patients showed improvement on the iNPH scale (p < 0.001). The iNPH scale score increased from 54.9 (45.6–64.3) [median, interquartile range (IQR)] preoperatively to 71.1 (59.9–79.5) postoperatively with a change of 15.0 (1.6–22.4). One patient could not be properly evaluated, and this patient’s condition was considered not improved. HRQoL was improved in 24 (83%) of 29 patients 6 months after surgery (p < 0.001). EQ-5D visual analogue scale increased from 55 (44.5–70) [median score (IQR)] preoperatively to 80 (58.75–85) postoperatively. Seven patients (23%) suffered from complications during the first 6 months: three patients had subdural haematomas that could be treated by temporarily increasing the shunt opening pressure; in four cases, surgical revision was required (for shunt dysfunction in three cases and infection in one case).

Discussion

This study shows that shunt surgery is an inexpensive and cost-effective treatment in iNPH. The average iNPH patient gains 2.2 life years and 1.7 QALY, a substantial gain for a patient aged around 70 years. In comparison, Donezepil treatment in Alzheimer’s disease gives an estimated gain of 0.11 QALYs at a considerably higher incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) [12], whereas endovascular thrombectomy in acute stroke adds 0.4 life years and 0.99 QALY [3].

The ICER for shunt surgery was €7,500/QALY and the cost per life year saved was €6,000. Even though we used a societal perspective and included other costs than healthcare costs, it is well below the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) nominal healthcare cost-per-QALY threshold for new interventions. Thus, shunt surgery would most probably have been strongly recommended if introduced as a new intervention. Compared to other established surgical procedures, shunt surgery has a low extra cost per QALY gained, matching, for example, hip replacement surgery (Table 4). Our results corroborate with a recent report by Kameda et al. [20] who also concluded that shunt surgery is cost effective, even though they found a higher cost/QALY (US$30,000–41,000/QALY equalling €28,000–39,000/QALY), probably due to a different study design with indirect estimations of costs and utility values.

This study was performed in a Swedish setting. We are, however, convinced that the results reported here are valid in developed countries throughout the world. The surgical procedure and the effects of shunting are comparable in most specialised centres. Also, costs for the “Deteriorated” state used here are within the range of the societal costs presented for other countries. The societal cost per person with dementia in Europe was estimated to US$24,565 (€22,168) and in North America to US$36,603 (€33,301) in 2009 years prices [46]. A recent study from Sweden, estimated the annual cost per person with dementia to €43,259 [1]. The yearly monetary cost in the United States per person with dementia was estimated to US$56,290 (€50,800) or US$41,689 (€37,620), depending on which method was used to value informal care [17].

The patients in our study were consecutively included, presented typical clinical features, and 67% were improved on the iNPH scale, a slightly lower figure than in many contemporary studies [43]. However, 83% reported improved HRQOL. The overall complication rate of 23% was somewhat high, but the revision rate of 13% is comparable with earlier studies [11]. All patients were diagnosed based on typical clinical symptoms and MRI findings according to international guidelines [34]. No supplementary tests, such as a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage test or lumbar infusion test, were used for inclusion. Inclusion of supplementary tests for the selection of patients for surgery has been discussed and recommended in several recent papers [14, 23, 27,28,29]. These tests are widely used due to their ability to identify shunt responders and adding these tests probably increase response rate to shunt surgery. The lower success rate in this study could be an effect of not using these tests. However, the European multicentre study [25] showed that when no supplementary tests are used, the number of patients improved by shunt surgery is 82%, which is similar to studies using such tests for inclusion. The dilemma of using or not using supplementary tests is further strengthened by the fact that iNPH patients that would benefit from surgery would be excluded by the use of supplementary tests as selection criteria [25]. Altogether, we consider the patient sample to be representative and the reported results valid. It was also established that the shunts worked in all the participants.

The input parameters used in the model were derived from the recent literature. Results from the European multicentre iNPH study [25], a large prospective longitudinal study with results comparable with those of many previous reports, and a recent systematic review of the outcome of shunt surgery in iNPH [20] formed the basis for the calculation of model outcome probabilities. A 73% probability of being improved after shunt surgery was used, corresponding to outcomes after more than 3 years reported in studies since 2006 [20], a figure that also corresponds to our experience and previous reports from our centre. Even if this figure is higher than recently reported in a large quality registry based study [37], we believe it is reasonable. For complication probabilities, data from a previous study at our centre, showing a rate of 13% for complications in need of intervention during the first year and 2% thereafter, were used [11]. These figures are comparable with other reports [43] and higher than in a recent report on cost-effectiveness [20] why we do not consider the complication rate underestimated. The mortality for the improved state was estimated according to the age-adjusted mortality rate for the normal Swedish population with an increase of 2.5 times. The same applies to the mortality for the deteriorated state, but with an additional 10% risk of mortality. We consider these input parameters to be the best possible estimates available. Also, the sensitivity analysis showed the robustness of the model—the results were not sensitive to major changes in long-term costs or utility weights—and, although some of the input parameters may be slightly uncertain, the main results will remain, even if the input parameters are varied.

The annual cost for the state “Deteriorated” was derived from the report by the National Board of Health and Welfare [35], where 78% of the cost is related to home care and the cost of living in a nursing home. According to the report, 42% of patients with dementia live in nursing homes, which is higher than the rate reported here for patients with iNPH. Shunt surgery will reduce patients’ need for assisted living; furthermore, in our experience, arranging accommodation in a residential home is often neglected for patients with suspected iNPH at the time of diagnosis, probably due to poor knowledge of the disorder and its prognosis. The natural course of iNPH is sparsely studied, with few reports in the literature, and, to our knowledge, there are no reports of the care burden and the cost of untreated patients. Also, for ethical reasons, a prospective study of the natural course would hardly be acceptable, considering the effective treatment available. We consider the reported cost of dementia disorders in Sweden a good estimate of the cost of untreated iNPH patients.

No supplementary tests, such as the CSF tap-test or lumbar infusion test, were used when including patients in this study. Costs for these tests are very low compared to the surgical procedure and are probably compensated by the extensive clinical testing performed on all of our patients. Again, sensitivity analysis showed that the results were not sensitive to major changes in parameters. We consider the results reported here valid also for centres using supplementary tests.

We used a societal perspective in the analysis and included the cost of informal care provided by relatives. However, we did not include the caregivers’ utility weight in the model. A previous review has shown that self-reported health was strongly related to the time spent caring and to the carer’s perceived burden [16]. Thus, since the cost of informal care is similar for the states “Improved” and “Deteriorated”, we assume that the burden for the caregivers is equal.

In general, simulation models have limitations when estimating cost effectiveness, often due to the lack of long-term data, resulting in major uncertainties of the long-term effects of the treatment in terms of costs, HRQoL and mortality. One weakness in our study is the small sample, mainly caused by the difficulty of undertaking such a detailed survey with personal interviews in larger samples. We chose to exclude seven patients aged <65 years and included only retired patients ≥65 years in order to get a patient group most representative of the target population. As stated earlier, we believe that the sample is representative, but further studies with larger samples are warranted. For this reason, results from other published studies have been included in the model, as probabilities of moving between the health states and the annual mortality rate. The uncertainties should be analysed with sensitivity analyses, as in this study.

One strength of the study is the rigorous recording of related costs after shunt surgery. All examinations were performed by a skilled occupational therapist (J.B.), either in connection with patient visits to the hospital or in the patient’s home. Relatives were always interviewed. Costs were also estimated through a meticulous evaluation of medical records. We believe that this objective procedure, evaluating qualitative and quantitative aspects of care, yields the most correct data possible. Further, HRQoL was measured using a reliable and widely used instrument.

Conclusions

This study shows that shunt surgery, an effective medical treatment for iNPH, is cost-effective and could therefore be recommended; shunt surgery as a standard treatment resulted in a gain of 2.2 life years and 1.7 quality-adjusted life years, along with an incremental cost per patient of €7,500/QALY. This is a substantial gain for elderly persons and a greater gain and lower cost/QALY than for many comparable standard interventions. In light of the increasing awareness of iNPH, we believe that the results reported here are highly relevant to the future allocation of healthcare resources.

References

Akerborg O, Lang A, Wimo A, Skoldunger A, Fratiglioni L, Gaudig M, Rosenlund M (2016) Cost of dementia and its correlation with dependence. J Aging Health 28:1448–1464

Andren K, Wikkelso C, Tisell M, Hellstrom P (2014) Natural course of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85:806–810

Aronsson M, Persson J, Blomstrand C, Wester P, Levin LA (2016) Cost-effectiveness of endovascular thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 86:1053–1059

Bergsneider M, Black PM, Klinge P, Marmarou A, Relkin N (2005) Surgical management of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57:S29–S39

Brean A, Eide PK (2008) Prevalence of probable idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus in a Norwegian population. Acta Neurol Scand 118:48–53

Brean A, Fredo HL, Sollid S, Muller T, Sundstrom T, Eide PK (2009) Five-year incidence of surgery for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus in Norway. Acta Neurol Scand 120:314–316

Briggs AHCK, Sculpher MJ (2006) Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford University Press, New York

Briggs AH, Gray AM (1999) Handling uncertainty in economic evaluations of healthcare interventions. BMJ 319:635–638

Burstrom K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F (2006) A comparison of individual and social time trade-off values for health states in the general population. Health Policy 76:359–370

Drummond F (2005) Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Farahmand D, Hilmarsson H, Hogfeldt M, Tisell M (2009) Perioperative risk factors for short term shunt revisions in adult hydrocephalus patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80:1248–1253

Getsios D, Blume S, Ishak KJ, Maclaine GD (2010) Cost effectiveness of donepezil in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a UK evaluation using discrete-event simulation. PharmacoEconomics 28:411–427

Grossman M (1972) On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J Polit Econ 80:223–585

Halperin JJ, Kurlan R, Schwalb JM, Cusimano MD, Gronseth G, Gloss D (2015) Practice guideline: idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: response to shunting and predictors of response: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American academy of neurology. Neurology 85:2063–2071

Hellstrom P, Klinge P, Tans J, Wikkelso C (2012) A new scale for assessment of severity and outcome in iNPH. Acta Neurol Scand 126:229–237

Hounsome N, Orrell M, Edwards RT (2011) EQ-5D as a quality of life measure in people with dementia and their carers: evidence and key issues. Value Health 14:390–399

Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM (2013) Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med 368:1326–1334

Jaraj D, Rabiei K, Marlow T, Jensen C, Skoog I, Wikkelso C (2014) Prevalence of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurology 82:1449–1454

Junkkari A, Sintonen H, Nerg O, Koivisto AM, Roine RP, Viinamaki H, Soininen H, Jaaskelainen JE, Leinonen V (2015) Health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Eur J Neurol 22:1391–1399

Kameda M, Yamada S, Atsuchi M, Kimura T, Kazui H, Miyajima M, Mori E, Ishikawa M, Date I, Sinphoni, Investigators S (2017) Cost-effectiveness analysis of shunt surgery for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus based on the SINPHONI and SINPHONI-2 trials. Acta Neurochir 159:995–1003

Kawamoto Y, Mouri M, Taira T, Iseki H, Masamune K (2015) Cost-effectiveness analysis of deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson’s disease in Japan. World Neurosurg 89:628–635

Kazui H, Mori E, Hashimoto M, Ishikawa M, Hirono N, Takeda M (2011) Effect of shunt operation on idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus patients in reducing caregiver burden: evidence from SINPHONI. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 31:363–370

Kiefer M, Unterberg A (2012) The differential diagnosis and treatment of normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Dtsch Arztebl Int 109:15–25 quiz 26

King JT Jr, Sperling MR, Justice AC, O'Connor MJ (1997) A cost-effectiveness analysis of anterior temporal lobectomy for intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosurg 87:20–28

Klinge P, Hellstrom P, Tans J, Wikkelso C (2012) One-year outcome in the European multicentre study on iNPH. Acta Neurol Scand 126:145–153

Malm J, Kristensen B, Stegmayr B, Fagerlund M, Koskinen LO (2000) Three-year survival and functional outcome of patients with idiopathic adult hydrocephalus syndrome. Neurology 55:576–578

Marmarou A, Bergsneider M, Klinge P, Relkin N, Black PM (2005) The value of supplemental prognostic tests for the preoperative assessment of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57:S17–S28 discussion ii-v

Mihalj M, Dolic K, Kolic K, Ledenko V (2016) CSF tap test - obsolete or appropriate test for predicting shunt responsiveness? A systemic review. J Neurol Sci 362:78–84

Mori E, Ishikawa M, Kato T, Kazui H, Miyake H, Miyajima M, Nakajima M, Hashimoto M, Kuriyama N, Tokuda T, Ishii K, Kaijima M, Hirata Y, Saito M, Arai H, Japanese Society of Normal Pressure H (2012) Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: second edition. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 52:775–809

NICE (2013) NICE. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/chapter/foreword. Last date accessed 12 May 2017

Petersen J, Hellstrom P, Wikkelso C, Lundgren-Nilsson A (2014) Improvement in social function and health-related quality of life after shunt surgery for idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg 121:776–784

Posnett J, Jan S (1996) Indirect cost in economic evaluation: the opportunity cost of unpaid inputs. Health Econ 5:13–23

Rasanen P, Paavolainen P, Sintonen H, Koivisto AM, Blom M, Ryynanen OP, Roine RP (2007) Effectiveness of hip or knee replacement surgery in terms of quality-adjusted life years and costs. Acta Orthop 78:108–115

Relkin N, Marmarou A, Klinge P, Bergsneider M, Black PM (2005) Diagnosing idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57:S4–16 discussion ii-v

Socialstyrelsen (2014) Demenssjukdomarnas samhällskostnader i Sverige 2012. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/19444/2014-6-3.pdf; http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2014/2014-6-3. Last date accessed 12 May 2017

Stein SC, Burnett MG, Sonnad SS (2006) Shunts in normal-pressure hydrocephalus: do we place too many or too few? J Neurosurg 105:815–822

Sundstrom N, Malm J, Laurell K, Lundin F, Kahlon B, Cesarini KG, Leijon G, Wikkelso C (2017) Incidence and outcome of surgery for adult hydrocephalus patients in Sweden. Br J Neurosurg 31:21–27

Sweden. SS Life Tables 2014. Accessed June 22 2016

Szende AWA (eds) (2014) Measuring self-reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D. EuroQol Group,Rotterdam, The Netherands. http://www.euroqol.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Documenten/PDF/Books/Measuring_Self-Reported_Population_Health_-_An_International_Perspective_based_on_EQ-5D.pdf. Last date accessed 2 May 2017

Tanaka N, Yamaguchi S, Ishikawa H, Ishii H, Meguro K (2009) Prevalence of possible idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus in Japan: the Osaki-Tajiri project. Neuroepidemiology 32:171–175

Tisell M, Hellstrom P, Ahl-Borjesson G, Barrows G, Blomsterwall E, Tullberg M, Wikkelso C (2006) Long-term outcome in 109 adult patients operated on for hydrocephalus. Br J Neurosurg 20:214–221

Tisell M, Hoglund M, Wikkelso C (2005) National and regional incidence of surgery for adult hydrocephalus in Sweden. Acta Neurol Scand 112:72–75

Toma AK, Papadopoulos MC, Stapleton S, Kitchen ND, Watkins LD (2013) Systematic review of the outcome of shunt surgery in idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurochir 155:1977–1980

Wijeysundera HC, Tomlinson G, Ko DT, Dzavik V, Krahn MD (2013) Medical therapy v. PCI in stable coronary artery disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Mak 33:891–905

Williams A (1990) EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16:199–208

Wimo A, Winblad B, Jonsson L (2010) The worldwide societal costs of dementia: estimates for 2009. Alzheimers Dement 6:98–103

Acknowledgements

We thank Jurgen Broeren (J.B.) for collecting data by interviewing patients and caregivers.

Funding

The Collection Foundation for Neurological Research, the Edit Jacobson Foundation and grants from the University of Gothenburg/Sahlgrenska University Hospital. The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Wikkelsø receives an honorarium from Johnson & Johnson for lecturing. The other authors report no disclosures. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee in Gothenburg, Sweden. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and/or their relatives.

Additional information

Comments

The authors provide an important analysis on the cost effectiveness of shunt surgery in idiopathic NPH. There is a definite need for such studies and thus far little has been done to obtain more insights regarding NPH. Idiopathic NPH remains to be an enigmatic disorder even today. The most relevant paradigm shift in the concept of NPH over the last four decades, however, was that gait disorders are seen now as the primary symptom of NPH and not dementia. Therefore, it might be considered questionable to use reported costs of dementia disorders in Sweden as an estimate for the costs of untreated NPH patients. Furthermore, we do not know if nowadays NPH is still underdiagnosed and undertreated. It would be worthwhile to scrutinise this issue and to explore whether there was a change in awareness—or whether clinicians sometimes even tend to overdiagnose NPH now.

Joachim K. Krauss

Hannover, Germany

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tullberg, M., Persson, J., Petersen, J. et al. Shunt surgery in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus is cost-effective—a cost utility analysis. Acta Neurochir 160, 509–518 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3394-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3394-7