Abstract

Objective

In recent years the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms (coiling) has progressively gained recognition, particularly after the publication of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) in 2002. Despite the fact that in ISAT middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms were clearly underrepresented, the study is often used as an argument to favor coiling above surgery in MCA aneurysms. Taken into account that MCA aneurysms are very well accessible for surgery, a contemporary assessment of the benefits of a preferred surgical strategy for MCA aneurysms was performed in a tertiary neurovascular referral center.

Methods

A prospectively kept single-center database of 151 consecutive patients with an MCA aneurysm was reviewed over a 6-year period (2001–2006). Long-term follow-up after surgical treatment of a ruptured MCA aneurysm was obtained in 74 out of 77 (96%) patients. The outcome was compared with relevant series in the literature.

Results

After a mean follow-up of 4.7 years, 59 out of 74 surgically treated patients (80%) with a ruptured MCA aneurysm had a good outcome (mRankin 0–2). All patients with an unruptured MCA aneurysm also had a good outcome after clipping. This is well-matched with the findings of the literature search, and competitive with the endovascular results.

Conclusion

Surgical clipping is recommended as the principal treatment strategy for MCA aneurysms. This is not only ethically defendable in view of the surgical results but also in line with a strategy to maintain surgical experience within centralized neurovascular centers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For many decades, neurosurgical treatment (clipping) has been the sole treatment for intracranial aneurysms. From the early 1990s on, endovascular treatment (coiling) has progressively become an alternative for clipping, which was enforced by the publication of the initial results of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) in 2002 [10].

The ISAT randomized patients with a ruptured intracranial aneurysm, in which both clipping and coiling were deemed valid, were compared for clinical outcome after either treatment option. Its results after a mean 1-year follow-up were in favor of coiling, showing an absolute risk reduction in dependency or death of 6.9%. However, the recently published 5-year follow-up data demonstrate that the differences in outcome of the two treatment modalities have vanished over the years [11]. In a modified intent-to-treat analysis, disregarding the mortality occurring before any treatment was instituted, all statistical differences have even disappeared [1]. Nevertheless, nowadays a substantial quantity of intracranial aneurysms, both ruptured and unruptured, are treated by endovascular techniques, also in vascular territories that were clearly underrepresented in ISAT, such as the middle cerebral artery (MCA). It is remarkable how quickly, particularly in Europe, the attitude has changed in favor of coiling of intracranial aneurysms, despite the lack of evidence. This tendency towards coiling has led to a significant decrease of the neurosurgical caseload, which has serious implications for the vascular neurosurgeons in each neurosurgical center, and for the training of neurovascular fellows.

The University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) is a large academic and community-based hospital with a high-volume neurovascular department, as a tertiary referral center delivering 24/7 emergency care for patients suffering an aneurysmatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH). The hospital covers a population of 1.7 million people in the northern part of The Netherlands, with a constant number of around 120 patients treated for an intracranial aneurysm each year. In the UMCG neurosurgical center the majority of MCA aneurysms are preferably treated by clipping, since MCA aneurysms are very well accessible for surgery, and because of the specific local angioarchitecture that often necessitates vascular remodeling of the MCA bifurcations, which is better coped with by surgical than by endovascular techniques.

In this paper a contemporary consecutive series of the preferred surgical strategy for MCA aneurysms is presented and balanced against the relevant literature.

Methods

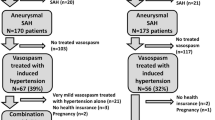

A retrospective review of a prospectively kept neurovascular database was performed for patients with an MCA aneurysm in the period from January 2001 until December 2006. In this 6-year period 151 consecutive patients with an MCA aneurysm were treated (Fig. 1). For each patient, the choice of the preferred treatment strategy (observation, clipping, or coiling) was made by a multidisciplinary team of neurosurgeons, neurologists and interventional neuroradiologists after clinical assessment and initial computed tomographic angiography (CTA) or conventional cerebral angiography. If treatment options were considered equal, in MCA aneurysms priority was given to surgery.

The records of all consecutive surgically treated patients were searched to obtain patient characteristics, characteristics of the aneurysm, treatment details, complications and follow-up. The clinical condition of all patients was classified according to the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies scale (WFNS) [7, 17]. Clinical outcome was graded according to the modified Rankin scale [2, 15].

Patients with an unruptured MCA aneurysm (WFNS 0) had a full assessment in the outpatient clinic and treatment was only instituted after thorough multidisciplinary counseling. Patients with a ruptured aneurysm of a good grade (WFNS 1–3) were, as a rule, treated within 72 h after the aSAH. In a minority of symptomatic patients, the treatment of the ruptured aneurysm was postponed because of co-morbidity or late referral. Patients with a ruptured aneurysm in a poor clinical condition (WFNS 4–5) were treated for acute hydrocephalus before making the final decision about the timing of the aneurysm treatment [18]. In case of an aSAH, treatment was at first selectively aimed at the ruptured aneurysm; additional unruptured aneurysms (coincidental aneurysms) were not treated in the same session, unless in the same surgical field.

All procedural complications and perioperative events were registered. To complete missing long-term follow-up, the family doctors of the patients were contacted.

Results

The patient characteristics are outlined in Table 1. The majority of the surgical patients with a ruptured MCA aneurysm were women (75%); the mean age was 52.3 years (range 33–79). The WFNS grade at admission was 1 or 2 in 67% of the cases. The aneurysm characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Most MCA aneurysms were larger than 5 mm (70%).

The treatment strategies of all consecutive patients are delineated in Fig. 1. The majority of MCA aneurysms was treated by surgery (105 patients). In 13 patients, the MCA aneurysm was coiled. Fourteen aSAH patients with a poor WFNS grade died before an attempt to treat the ruptured aneurysm could be made. Nineteen patients with an asymptomatic aneurysm were left untreated: 17 patients had an aneurysm judged too small for treatment according to the recommendations of the ISUIA study [19]; two patients rejected the advised treatment.

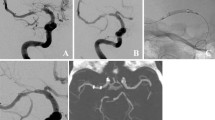

Surgical clipping of an MCA aneurysm was performed following an aSAH in 77 patients, of which the majority (83%) was treated within 72 h following the hemorrhage. Thirteen patients had postponed clipping of the ruptured aneurysm. Two patients harbored a coincidental (contralateral) MCA aneurysm and had a second surgical procedure. Twenty-three surgically treated patients presented with a significant hematoma, requiring an immediate evacuation of the clot in 20 patients. In 95 of 107 procedures (89%) the surgeon reported a full occlusion of the aneurysm.

Procedural and perioperative events are depicted in Table 3. Since both clinical and non-clinical (TCD) vasospasm was recorded as a postoperative event, only 32 of 105 patients (30.5%) experienced a fully uneventful course. Preoperative subarachnoid rebleeding occurred 11 times (in two cases twice in the same patient). Postoperative rebleeding of a clipped MCA aneurysm occurred once, leading to a poor outcome. The other postoperative rebleeding was from a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm in a patient with a coincidental MCA aneurysm.

Follow-up of the surgically treated symptomatic patients at 2 months was complete for all but one patient (99%). The mean follow-up was 4.7 years, obtained in 96% of the patients. The outcome was graded mRankin 0–2 in 80% of the cases (Fig. 2). During follow-up, four patients died from an unrelated cause, all more than 1 year after the aSAH and treatment.

Patients with a significant intracerebral hematoma (ICH) (n = 23) presented with a worse WFNS grade than the average study population (WFNS 1–2 in only 39% of cases), but nevertheless in 69% of cases their outcome was good (mRankin 0–2). If these patients had been excluded in the outcome analysis, outcome would have been calculated as mRankin 0–2 in 88% of the patients.

All 19 patients with a surgically treated asymptomatic (not coincidental) MCA aneurysm had a good outcome at the latest follow-up (mRankin 0–2). In the other patients with asymptomatic aneurysms, follow-up was discontinued in five cases because of patient-related factors, e.g., co-morbidity or age. Two patients refused to have a follow-up. Eleven patients harboring an asymptomatic aneurysm had a radiological follow-up after 1 year; no enlargement of their aneurysm was found on digital subtraction angiography (DSA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) examination.

Discussion

Literature

Surgical series from the era before ISAT (before 2002) have demonstrated good surgical results for MCA aneurysms. Nevertheless, in many institutions the surgical experience has diminished during the last decade. This is confirmed by a search of the PubMed internet database from 2001 on, yielding very few surgical reports. In an extensive review of the Finnish experience with MCA aneurysms, Dashti et al. stated that these aneurysms are still best treated surgically [4–6]. Prat and Galeano [13] described 12 patients with a significant intracranial hematoma due to an MCA aneurysm that presented with WFNS grade 4 or 5, of which only five patients had a good or moderate outcome. The literature search also revealed a recent publication by Quadros et al. [14] on the coiling of MCA aneurysms in 55 patients. They concluded that coiling was effective in preventing a rerupture of the symptomatic aneurysm (mean follow-up 14 months); however, with a total occlusion of the ruptured MCA aneurysm in merely 42% of their cases. In addition, only 57% of patients with a ruptured MCA aneurysm in their study had a good outcome after 1 year and six patients (18%) died. These endovascular results are clearly unfavorable in comparison with the results of surgical studies, including the present study showing 89% intraoperative total occlusion and 80% good outcome.

UMCG surgical series

After a mean 4.7-year follow-up, the clinical outcome of 77 patients with a ruptured aneurysm was graded good (mRankin 0–2) in 80% of the cases. Excluding the patients with a significant ICH would even lead to a good outcome in 88% of the patients. Also, all patients treated for an unruptured MCA aneurysm were graded with a good outcome after clipping; on the whole unchanged in comparison with the preoperative condition. These results are far better than the related endovascular series for MCA aneurysms in the literature.

All perioperative events are outlined in Table 3. Most events were related to the aSAH and not to the surgical procedure. Postoperative rebleeding of an MCA aneurysm occurred in one patient with an incompletely clipped giant aneurysm that had presented with a large ICH and a WFNS grade 4 SAH. Postoperative epidural or subcutaneous hematoma occurred in four out of 105 surgically treated patients. Seizures were encountered in four surgically treated patients. Ventriculitis occurred in seven patients, without exception related to an external cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunt.

Scientific, ethical and political reflections

In ISAT, the MCA aneurysms were noticeably underrepresented. This is almost certainly due to the inclusion criteria that required that both clip and coil were considered equivalent in leading to a definite cure. As a consequence, MCA aneurysms presenting with a hematoma or having vascular branches originating from its neck were not randomized, whereas these features often occur. Also, a significant accompanying hematoma that needs surgical evacuation is frequently encountered after MCA aneurysm rupture. Nevertheless, particularly in Europe, the ISAT results are applied to the whole spectrum of cerebral aneurysms, including MCA aneurysms, despite the fact that good results of aneurysm clipping are still reported [3, 12]. In addition, recent publications on the long-term results of the ISAT have shown that after 5-year follow-up the clinical outcome after coiling is no longer superior to a surgical strategy, due to persistent higher rebleeding rates and a wider need for re-treatment after coiling [8, 9, 16].

Everyday clinical practice requires that choices between the different treatment modalities for patients with an aSAH are being made on a scientific basis. ISAT has proven its value in this decision-making process, particularly for aneurysms of the carotid artery and the anterior cerebral artery, but its recommendations cannot be used as a license to frankly extrapolate in favor of coiling of MCA aneurysms. Also, it has to be taken into account that to overcome the angioarchitectural disadvantages of the MCA anatomy there has been over the years an increased use of remodeling balloons and stents in addition to coiling. These added technical novelties add to the morbidity and mortality, and have never been tested in a randomized study to be better or safer than coiling alone or surgery. It is remarkable that the devices are frequently innovated and taken into clinical use without any proof of their superiority. In contrast, surgical treatment of MCA aneurysms is straightforward, with the possibility to remodel the aneurysm in order to obtain a perfect neck occlusion and, if necessary, to remove an associated hematoma. As such, surgical clipping should be recognized as the preferred treatment of MCA aneurysms.

Apart from the technical aspects, there is another serious concern. Particularly in Europe, the notable rise in endovascular procedures has led to a significant decline of the surgical caseload. This raises questions about the maintenance of surgical skills and the ability to train future neurovascular surgeons. A loss of surgical neurovascular expertise will certainly lead to a downward spiral in the quality of the overall treatment of intracranial aneurysms. It is extremely important to ensure that the high-quality standards of today are also guaranteed tomorrow. Caseloads should be high, in order to preserve neurovascular experience at the highest level. Obviously, regional and nationwide centralization of neurovascular care and training will be the only way to secure this.

Conclusion

This contemporary study confirms that good results are achieved with clipping of MCA aneurysms. All attempts to treat MCA aneurysms endovascularly, often with the use of novel (not clinically tested) endovascular devices, are unjustified in a situation where an excellent surgical solution is at hand. Also, the treatment of cerebral aneurysms should be restricted to specialized regional centers with a high caseload, which are able to provide full-time high-level care by a team of experienced vascular neurosurgeons and interventional neuroradiologists, to guarantee optimal care for this category of patients.

References

Bakker NA, Metzemaekers JD, Groen RJ, Mooij JJ, Van Dijk JM (2010) International subarachnoid aneurysm trial 2009: endovascular coiling of ruptured intracranial aneurysms has no significant advantage over neurosurgical clipping. Neurosurgery 66:961–962

Bonita R, Beaglehole R (1988) Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke 19:1497–1500

Crocker M, Corns R, Hampton T, Deasy N, Tolias CM (2008) Vascular neurosurgery following the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial: modern practice reflected by subspecialization. J Neurosurg 109:992–997

Dashti R, Hernesniemi J, Niemela M, Rinne J, Lehecka M, Shen H, Lehto H, Albayrak BS, Ronkainen A, Koivisto T, Jaaskelainen JE (2007) Microneurosurgical management of distal middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Surg Neurol 67:553–563

Dashti R, Hernesniemi J, Niemela M, Rinne J, Porras M, Lehecka M, Shen H, Albayrak BS, Lehto H, Koroknay-Pal P, de Oliveira RS, Perra G, Ronkainen A, Koivisto T, Jaaskelainen JE (2007) Microneurosurgical management of middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysms. Surg Neurol 67:441–456

Dashti R, Rinne J, Hernesniemi J, Niemela M, Kivipelto L, Lehecka M, Karatas A, Avci E, Ishii K, Shen H, Pelaez JG, Albayrak BS, Ronkainen A, Koivisto T, Jaaskelainen JE (2007) Microneurosurgical management of proximal middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Surg Neurol 67:6–14

Drake C (1988) Report of World Federation of Neurosurgical Surgeons Committee on a universal subarachnoid haemorrhae grading scale. J Neurosurg 68:985–986

Johnston SC, Dowd CF, Higashida RT, Lawton MT, Duckwiler GR, Gress DR (2008) Predictors of rehemorrhage after treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: the Cerebral Aneurysm Rerupture After Treatment (CARAT) study. Stroke 39:120–125

Mitchell P, Kerr R, Mendelow AD, Molyneux A (2008) Could late rebleeding overturn the superiority of cranial aneurysm coil embolization over clip ligation seen in the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial? J Neurosurg 108:437–442

Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, Sandercock P, Clarke M, Shrimpton J, Holman R (2002) International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised trial. Lancet 360:1267–1274

Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Birks J, Ramzi N, Yarnold J, Sneade M, Rischmiller J (2009) Risk of recurrent subarachnoid haemorrhage, death, or dependence and standardised mortality ratios after clipping or coiling of an intracranial aneurysm in the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT): long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol 8:427–433

Nussbaum ES, Madison MT, Myers ME, Goddard J (2007) Microsurgical treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. A consecutive surgical experience consisting of 450 aneurysms treated in the endovascular era. Surg Neurol 67:457–464

Prat R, Galeano I (2007) Early surgical treatment of middle cerebral artery aneurysms associated with intracerebral haematoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 109:431–435

Quadros RS, Gallas S, Noudel R, Rousseaux P, Pierot L (2007) Endovascular treatment of middle cerebral artery aneurysms as first option: a single center experience of 92 aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28:1567–1572

Rankin J (1957) Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. II. Prognosis. Scott Med J 2:200–215

Ryttlefors M, Enblad P, Kerr RS, Molyneux AJ (2008) International subarachnoid aneurysm trial of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling: subgroup analysis of 278 elderly patients. Stroke 39:2720–2726

Teasdale GM, Drake CG, Hunt W, Kassell N, Sano K, Pertuiset B, De Villiers JC (1988) A universal subarachnoid hemorrhage scale: report of a committee of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 51:1457

ter Laan M, Mooij JJ (2006) Improvement after treatment of hydrocephalus in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: implications for grading and prognosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 148:325–328

Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J, III, Meissner I, Brown RD Jr, Piepgras DG, Forbes GS, Thielen K, Nichols D, O’Fallon WM, Peacock J, Jaeger L, Kassell NF, Kongable-Beckman GL, Torner JC (2003) Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet 362:103–110

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comments

We could not agree more with this nice paper showing the superiority of clipping of MCA aneurysms in line with our [1–3] and others’ experience. It has been really surprising how easily the neurosurgical community has changed from proven microsurgical clipping of aneurysms to endovascular coiling based only on one poorly randomized study, the ISAT, and the idea of not having to open the skull, which is not dangerous as such if performed by (experienced) neurosurgeons. Even the scar is left behind the hair-line. It may be more difficult to conduct a randomized study like this for relatively rare SAH or neurosurgical patients in general than in other fields of medicine, but it usually still takes several studies with similar results to convince the clinicians to change their policies. As the authors state, since the first ISAT paper came out the results have been applied to treat all possible aneurysms, regardless of their size, form, location or rupture state (even with ICH!) with coils, and recently even with stents. Stents or stent-assisted coiling have not been tested in a randomized way against microsurgical clipping regarding safety and efficacy, but without any doubt they must add morbidity and mortality not only because they require long-term anticoagulation. Furthermore, nobody knows the long-term patency or the risk of migration of the stents. Nobody talks about the necessity of clinical and radiological follow-up of patients after uncertain endovascular therapy making the patients very worried, with additional costs to the patients and society, instead of clipping the aneurysms with proven efficacy over several decades. There are inadvertent branch occlusions and also unexpected neck remnants after clipping by very experienced neurosurgeons [6]. Therefore, it is very important to confirm the result of clipping with intraoperative indocyanine green (ICG) angiography [4] followed by postoperative CTA, as we nowadays prefer. If clipping is preferred, DSA has a role only in complex and giant aneurysms.

The long-term results of ISAT have proven to be equal between clipping and coiling, but still clipping of aneurysms is many times considered to be almost a criminal act or being a sign of a real dinosaur. This is based on what? Instead, we consider endovascular therapy of MCA aneurysms to be extremely poor treatment of patients as these always re-canalize and usually after a very short period of time necessitating either re-coiling to be followed by re-canalization again or then clipping with removal of the coils which may be a true challenge at that late point [9]. Coiling ruptured MCA aneurysms with ICH can really be considered as criminal in not letting the patients have the best possible treatment and recovery, which is clipping of the aneurysm and removal of the clot at the same time as soon as possible.

Unfortunately, based on a single debatable study, the number of neurosurgeons being able to perform safe clipping of cerebral aneurysms has decreased markedly. The cases left are more and more demanding. As the authors state, the treatment of cerebral aneurysms should be centralized into dedicated centers with a 24/7 microsurgical and endovascular service, not forgetting modern neuroanesthesia for the optimal results [5, 7, 8].

Mika Niemelä

Juha Hernesniemi

Helsinki, Finland

1. Dashti R, Rinne J, Hernesniemi J, Niemelä M, Kivipelto L, Lehecka M, Karatas A, Avci E, Ishii K, Shen H, Pleaez J, Albayrak B, Ronkainen A, Koivisto T, Jääskeläinen J (2007) Microneurosurgical management of proximal middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Surg Neurol 67:6–14

2. Dashti R, Hernesniemi J, Niemelä M, Rinne J, Porras M, Lehecka M, Shen H, Albayrak BS, Lehto H, Koroknay-Pal P, Sillero R, Perra G, Ronkainen A, Koivisto T, Jääskeläinen JE (2007) Microneurosurgical management of middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysms. Surg Neurol 67:441–456

3. Dashti R, Hernesniemi J, Niemelä M, Rinne J, Lehecka M, Shen H, Lehto H, Albayrak B, Ronkainen A, Koivisto T, Jääskeläinen J (2007) Microneurosurgical management of distal middle cereberal artery aneurysms. Surg Neurol 67:553–563

4. Dashti R, Laakso A, Niemelä M, Porras M, Hernesniemi JA (2009) Microscope-integrated near-infrared green video angiography during surgery of intracranial aneurysms: the Helsinki experience. Surg Neurol 71(5):543–550

5. Hernesniemi J, Niemelä M, Kivipelto L, Ishii K, Rinne J, Ronkainen J, Kivisaari R, Shen H, Karatas A, Lehecka M, Frösen J, Piippo A, Jääskeläinen J (2005) Some basic principles in microneurosurgery of the brain. A review. Surg Neurol 64:195–200

6. Kivisaari RP, Porras M, Öhman J, Siironen J, Ishii K, Hernesniemi J (2004) Routine cerebral angiography after surgery for saccular aneurysms – is it worth? Neurosurgery 55:1015–1024

7. Niemelä M, Koivisto T, Kivipelto L, Ishii K, Rinne J, Ronkainen A, Kivisaari R, Shen H, Karatas A, Lehecka M, Frösen J, Piippo A, Jääskeläinen J, Hernesniemi J (2005) Microsurgical clipping of cerebral aneurysms after the ISAT Study. Acta Neurochir Suppl 94:3–6

8. Randell T, Niemelä M, Kyttä J, Tanskanen P, Määttänen M, Karatas A, Ishii K, Dashti R, Hernesniemi J (2006) Principles of neuroanesthesia in aneurysmal SAH: the Helsinki experience. Surg Neurol 66:382–388

9. Romani R, Lehto H, Horcajadas A, Laakso A, Kivisaari R, Fraunberg M, Niemelä M, Rinne J, Hernesniemi J (2011) Microsurgery for previously coiled aneurysms: experience on 81 patients Neurosurgery 68:140–154

The authors of this study, from an experienced and well-recognized neurovascular center, published their results with the treatment of 151 consecutive patients with middle cerebral aneurysms (MCAs). They have a policy of treating MCA aneurysms preferentially with open microsurgery. The point of the article is to show that their results justify this policy. Of the 77 patients with ruptured aneurysms that were treated by clipping, they obtained a “good” outcome (modified Rankin 0–2) in 80%. Additionally, all the patients with an unruptured MCA aneurysm treated by clipping had a good outcome.

The authors feel strongly that their surgical results as well as that of other experienced surgeons with clipping of MCA aneurysms are better than the results obtained with endovascular coiling. However, they do not provide us with a detailed comparison of their results and that of other microsurgical series in the literature with the results of endovascular coiling of MCA aneurysms. I understand that a direct comparison of results would be very difficult because generally in both surgical and endovascular series there is a significant bias in favor of one treatment over another, as well as in terms of which aneurysms are selected for coiling and which are selected for surgery. The problem is that in the absence of scientifically valid comparisons or, preferably, randomized studies (and I agree with the authors that the ISAT study did not address adequately MCA aneurysms), statements such as “surgical clipping should be recognized as the preferred treatment of MCA aneurysms” and “all attempts to treat MCA aneurysms endovascularly, often with the use of novel (not clinically tested) endovascular devices are unjustified” are only personal opinions and should be taken as such by the readership. I confess that I personally agree with the authors and prefer clipping for most MCA aneurysms, although certainly not all, since, for example, in patients in poor neurologic condition after SAH, I prefer coiling if at all possible. However, I recognize that this is only a personal bias that may change in time if convincing scientific evidence to the contrary emerges.

Another caveat that those of us that favor microsurgery should acknowledge, in all fairness to our endovascular colleagues, is that although our main criticism of coiling is that it frequently results in incomplete occlusion of the aneurysm and/or recanalization in the future, we have generally not subjected our clipped patients to long-term angiographic follow-up to prove that indeed clipping is a definitive treatment, as we commonly assume. An example of this problem is the present series, in which the authors have an enviable clinical follow-up but apparently no long-term angiographic follow-up, except in a few patients. Furthermore, even if we accept that coiling not infrequently results in an incompletely occluded aneurysm, convincing evidence is emerging that the risk of hemorrhage from incompletely coiled aneurysms is very, very low.

I would also like to comment on a difficult issue that the authors address rather emphatically and that is the fear that as endovascular treatment continues to gain in popularity, we are gradually losing our open vascular surgical skills and our ability to train adequately the younger generation of vascular neurosurgeons. While obviously sharing this serious concern with the authors, I object to the implication that this should be a consideration when faced with a decision to treat or coil an aneurysm in a particular patient. I feel strongly, and I suspect that the authors do too, that in any particular patient the aneurysm should be treated in whatever manner we feel is safer and most efficacious for that particular patient, regardless of any other considerations. For now, I agree with the authors that in many, if not most MCA aneurysms, clipping is the preferred option; however, I acknowledge the lack of scientific support for this opinion and I would like to keep an open mind as to what the future will bring as endovascular technology and expertise improves at what I feel is a much steeper rate than the improvements that I foresee in microsurgical clipping techniques.

Roberto Heros

Miami, USA

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Dijk, J.M.C., Groen, R.J.M., Ter Laan, M. et al. Surgical clipping as the preferred treatment for aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery. Acta Neurochir 153, 2111–2117 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-011-1139-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-011-1139-6