Abstract

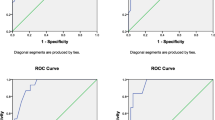

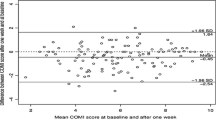

In studies evaluating the efficacy of clinical interventions, it is of paramount importance that the functional outcome measures are responsive to clinically relevant change. Knowledge thereof is in fact essential for the choice of instrument in clinical trials and for clinical decision-making. This article endeavours to investigate the sensitivity, specificity and clinically significant improvement (responsiveness) of the Danish version of the Oswestry disability index (ODI) in two back pain populations. Two hundred and thirty three patients with low back pain (LBP) and/or leg pain completed a questionnaire booklet at baseline and 8 weeks follow-up. Half of the patients were seen in the primary (PrS) and half in the secondary sectors (SeS) of the Danish Health Care System. The booklet contained the Danish version of the ODI, along with the Roland Morris Questionnaire, the LBP Rating Scale, the SF36 (physical function and bodily pain scales) and a global pain rating. At follow-up, a 7-point transition question (TQ) of patient perceived change and a numeric rating scale relating to the importance of the change were included. Responsiveness was operationalised using three strategies: change scores, standardised response means (SRM) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses. All methods revealed acceptable responsiveness of the ODI in the two patient populations which was comparable to the external instruments. SRM of the ODI change scores at 2 months follow-up was 1.0 for PrS patients and 0.3 for SeS (raw and percentage). A minimum clinically important change (MCID) from baseline score was established at 9 points (71%) for PrS patients and 8 points (27%) for SeS patients using ROC analyses. This was dependable on the baseline entry score with the MCID increasing with 5 points for every 10 points increase in the baseline score. We conclude that the Danish version of the ODI has comparable responsiveness to other commonly used functional status measures and is appropriate for use in low back pain patients receiving conservative care in both the primary and secondary sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It might seem odd that the average of 13 and 10 points for the PrS and SeS patients does not equal the 15 point for the whole population, however, this is an example of Simpson’s Paradox.

References

Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, Koke AJ (1996) Responsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain 65:71–76

Bombardier C (2000) Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders. Introduction. Spine 25:3097–3099

Kopec JA, Esdaile JM (1995) Functional disability scales for back pain. Spine 20:1943–1949

Schaufele MK, Boden SD (2003) Outcome research in patients with chronic low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am 34:231–237

Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B et al (1998) Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine 23:2003–2013

Bombardier C (2000) Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine 25:3100–3103

Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK (2005) Functional status and disability questionnaires: What do they assess? A systematic review of back-specific outcome questionnaires. Spine 30:130–140

Roland M, Fairbank J (2000) The Roland-Morris disability questionnaire and the Oswestry disability questionnaire. Spine 25:3115–3124

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB (2000) The Oswestry disability index. Spine 25:2940–2952

Muller U, Roeder C, Dubs L, Duetz MS, Greenough CG (2004) Condition-specific outcome measures for low back pain. Part II: Scale construction. Eur Spine J 13:314–324

Muller U, Duetz MS, Roeder C, Greenough CG (2004) Condition-specific outcome measures for low back pain. Part I: Validation. Eur Spine J 13:301–313

Kirshner B, Guyatt G (1985) A methodological framework for assessing health indices. J Chronic Dis 38:27–36

Guyatt GH, Kirshner B, Jaeschke R (1992) Measuring health status: what are the necessary measurement properties? J Clin Epidemiol 45:1341–1345

Beaton DE, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C (1997) Evaluating changes in health status: reliability and responsiveness of five generic health status measures in workers with musculoskeletal disorders. J Clin Epidemiol 50:79–93

Deyo RA, Inui TS (1984) Toward clinical applications of health status measures: sensitivity of scales to clinically important changes. Health Serv Res 19:277–289

Fitzpatrick R, Ziebland S, Jenkinson C, Mowat A, Mowat A (1992) Importance of sensitivity to change as a criterion for selecting health status measures. Qual Health Care 1:89–93

Liang MH (2000) Longitudinal construct validity: establishment of clinical meaning in patient evaluative instruments. Med Care 38:II84–II90

Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Wiersinga WM, Prummel MF, Bossuyt PM (2003) On assessing responsiveness of health-related quality of life instruments: guidelines for instrument evaluation. Qual Life Res 12:349–362

Bolton JE, Breen AC (1999) The Bournemouth Questionnaire: a short-form comprehensive outcome measure. I. Psychometric properties in back pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 22:503–510

Lydick E, Epstein RS (1993) Interpretation of quality of life changes. Qual Life Res 2:221–226

Stratford PW, Binkley FM, Riddle DL (1996) Health status measures: strategies and analytic methods for assessing change scores. Phys Ther 76:1109–1123

Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR (2003) Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol 56:395–407

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Katz JN, Wright JG (2001) A taxonomy for responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol 54:1204–1217

Husted JA, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, Gladman DD (2000) Methods for assessing responsiveness: a critical review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 53:459–468

Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF (1989) Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care 27:S178–S189

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (2003) Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 41:582–592

Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR (2002) Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc 77:371–383

Beaton DE, Boers M, Wells GA (2002) Many faces of the minimal clinically important difference (MCID): a literature review and directions for future research. Curr Opin Rheumatol 14:109–114

Fitzpatrick R, Ziebland S, Jenkinson C, Mowat A, Mowat A (1993) Transition questions to assess outcomes in rheumatoid-arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 32:807–811

Kopec JA, Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Abenhaim L, Wood-Dauphinee S, Lamping DL et al (1995) The Quebec back pain disability Scale. Measurement properties. Spine 20:341–352

Fischer D, Stewart AL, Bloch DA, Lorig K, Laurent D, Holman H (1999) Capturing the patient’s view of change as a clinical outcome measure. JAMA 282:1157–1162

Farrar JT, Portenoy RK, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Strom BL (2000) Defining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measures. Pain 88:287–294

Guyatt GH, Norman GR, Juniper EF, Griffith LE (2002) A critical look at transition ratings. J Clin Epidemiol 55:900–908

Fritz JM, Piva SR (2003) Physical impairment index: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with acute low back pain. Spine 28:1189–1194

Barck AL (1999) Measurement of clinical change caused by knee replacement. Conventional score or special change indexes? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 119:76–78

Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH (1989) Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials 10:407–415

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE (1994) Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol 47:81–87

Redelmeier DA, Guyatt GH, Goldstein RS (1996) Assessing the minimal important difference in symptoms: a comparison of two techniques. J Clin Epidemiol 49:1215–1219

Norman GR, Stratford P, Regehr G (1997) Methodological problems in the retrospective computation of responsiveness to change: the lesson of Cronbach. J Clin Epidemiol 50:869–879

Brant R, Sutherland L, Hilsden R (1999) Examining the minimum important difference. Stat Med 18:2593–2603

Deyo RA, Centor RM (1986) Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostic test performance. J Chronic Dis 39:897–906

Deyo RA, Diehr P, Patrick DL (1991) Reproducibility and responsiveness of health status measures. Statistics and strategies for evaluation. Control Clin Trials 12:142S–158S

Lauridsen HH, Hartvigsen J, Manniche C, Korsholm L, Grunnet-Nilsson N (2005) Danish version of the Oswestry Disability Index for patients with low back pain. Part 1: cross-cultural adaptation, reliability and validity in two different back pain populations. Eur Spine J (in press)

Albert HB, Jensen AM, Dahl D, Rasmussen MN (2003) Criteria validation of the Roland Morris questionnaire. A Danish translation of the international scale for the assessment of functional level in patients with low back pain and sciatica (in Danish). Ugeskr Laeger 165:1875–1880

Manniche C, Asmussen K, Lauritsen B, Vinterberg H, Kreiner S, Jordan A (1994) Low Back Pain Rating scale: validation of a tool for assessment of low back pain. Pain 57:317–326

Bjorner JB, Thunedborg K, Kristensen TS, Modvig J, Bech P (1998) The Danish SF–36 Health Survey: translation and preliminary validity studies. J Clin Epidemiol 51:991–999

Bjorner JB, Kreiner S, Ware JE, Damsgaard MT, Bech P (1998) Differential item functioning in the Danish translation of the SF-36. J Clin Epidemiol 51:1189–1202

Bjorner JB, Damsgaard MT, Watt T, Groenvold M (1998) Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability of the Danish SF-36. J Clin Epidemiol 51:1001–1011

Guyatt GH, Berman LB, Townsend M, Taylor DW (1985) Should study subjects see their previous responses. J Chronic Dis 38:1003–1007

Guyatt GH, Townsend M, Keller JL, Singer J (1989) Should study subjects see their previous responses—data from a randomized control trial. J Clin Epidemiol 42:913–920

Bjorner JB, Damsgaard MT, Watt T, Bech P, Rasmussen NK, Modvig J et al (1997) Danish Manual to the SF36. LIF, Lægemiddelindutriforeningen

Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM (2001) Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 94:149–158

Bolton JE (2004) Sensitivity and specificity of outcome measures in patients with neck pain: detecting clinically significant improvement. Spine 29:2410–2417

Hagg O, Fritzell P, Oden A, Nordwall A (2002) Simplifying outcome measurement: evaluation of instruments for measuring outcome after fusion surgery for chronic low back pain. Spine 27:1213–1222

Jones PW (2002) Interpreting thresholds for a clinically significant change in health status in asthma and COPD. Eur Respir J 19:398–404

Stratford PW, Spadoni G, Kennedy D, Westaway MD, Alcock GK (2002) Seven points to consider when investigating a measure’s ability to detect change. Physiother Can 54:16–24

Guyatt GH (2000) Making sense of quality-of-life data. Med Care 38:II175–II179

Hanley JA (1989) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) methodology: the state of the art. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging 29:307–335

de Vet HC, Bouter LM, Bezemer PD, Beurskens AJ (2001) Reproducibility and responsiveness of evaluative outcome measures. Theoretical considerations illustrated by an empirical example. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 17:479–487

Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Riddle DL, Guyatt GH (1998) Sensitivity to change of the Roland-Morris back pain questionnaire: part 1. Phys Ther 78:1186–1196

Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B (1983) The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 17:45–56

Williamson A, Hoggart B (2005) Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 14:798–804

Mannion AF, Junge A, Grob D, Dvorak J, Fairbank JC (2005) Development of a German version of the Oswestry Disability Index. Part 2: sensitivity to change after spinal surgery. Eur Spine J (in press)

Vickers AJ (2001) The use of percentage change from baseline as an outcome in a controlled trial is statistically inefficient: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol 1:6

Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK (2004) Concurrent comparison of responsiveness in pain and functional status measurements used for patients with low back pain. Spine 29:E492–E501

Garratt AM, Klaber MJ, Farrin AJ (2001) Responsiveness of generic and specific measures of health outcome in low back pain. Spine 26:71–77

Suarez-Almazor ME, Kendall C, Johnson JA, Skeith K, Vincent D (2000) Use of health status measures in patients with low back pain in clinical settings. Comparison of specific, generic and preference-based instruments. Rheumatology (Oxford) 39:783–790

Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ (2001) A comparison of a modified Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire and the Quebec back pain disability scale. Phys Ther 81:776–788

Hagg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A (2003) The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 12:12–20

Stratford PW, Binkley JM (1997) Measurement properties of the RM-18. A modified version of the Roland-Morris Disability Scale. Spine 22:2416–2421

Davidson M, Keating JL (2002) A comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsiveness. Phys Ther 82:8–24

Taylor SJ, Taylor AE, Foy MA, Fogg AJ (1999) Responsiveness of common outcome measures for patients with low back pain. Spine 24:1805–1812

Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB (1995) Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine 20:1899–1908

Leclaire R, Blier F, Fortin L, Proulx R (1997) A cross-sectional study comparing the Oswestry and Roland-Morris functional disability scales in two populations of patients with low back pain of different levels of severity. Spine 22:68–71

Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, Gill C, Finch E (1994) Assessing change over time in patients with low back pain. Phys Ther 74:528–533

Coste J, Delecoeuillerie G, Cohen dL, LeParc JM, Paolaggi JB (1994) Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: an inception cohort study in primary care practice. BMJ 308:577–580

Lonnberg F (1997) The management of back problems among the population. I. Contact patterns and therapeutic routines. Ugeskr Laeger 159:2207–2214 [In Danish]

Beaton DE (2000) Understanding the relevance of measured change through studies of responsiveness. Spine 25:3192–3199

Bombardier C, Hayden J, Beaton DE (2001) Minimal clinically important difference. Low back pain: outcome measures. J Rheumatol 28:431–438

Riddle DL, Stratford PW, Binkley JM (1998) Sensitivity to change of the Roland-Morris back pain questionnaire: part 2. Phys Ther 78:1197–1207

Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, Finch E, Gill C, Moreland J (1996) Defining the minimum level of detectable change for the Roland-Morris questionnaire. Phys Ther 76:359–365

Stratford PW, Binkley JM (1999) Applying the results of self-report measures to individual patients: an example using the Roland-Morris questionnaire. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 29:232–239

Rantanen P (2001) Physical measurements and questionnaires as diagnostic tools in chronic low back pain. J Rehabil Med 33:31–35

Fairbank J, Frost H, Wilson-MacDonald J, Yu LM, Barker K, Collins R (2005) Randomised controlled trial to compare surgical stabilisation of the lumbar spine with an intensive rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low back pain: the MRC spine stabilisation trial. BMJ 330:1233

Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A (2002) Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective multicenter randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group. Spine 27:1131–1141

Acknowledgments

We thank Jytte Johannesen and Ida Bhanderi for administering the questionnaires. Furthermore, we would like to thank the management and staff at Backcenter Funen for their enthusiastic participation in the project. A special thanks to the seven chiropractic clinics for their involvement in recruiting patients for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Part 1 of this article is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0117-9

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0260-3

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lauridsen, H.H., Hartvigsen, J., Manniche, C. et al. Danish version of the Oswestry disability index for patients with low back pain. Part 2: Sensitivity, specificity and clinically significant improvement in two low back pain populations. Eur Spine J 15, 1717–1728 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0128-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0128-6