Abstract

Purpose

Prehabilitation is increasingly offered to patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) undergoing surgery as it could prevent complications and facilitate recovery. However, implementation of such a complex multidisciplinary intervention is challenging. This study aims to explore perspectives of professionals involved in prehabilitation to gain understanding of barriers or facilitators to its implementation and to identify strategies to successful operationalization of prehabilitation.

Methods

In this qualitative study, semi-structured interviews were performed with healthcare professionals involved in prehabilitation for patients with CRC. Prehabilitation was defined as a preoperative program with the aim of improving physical fitness and nutritional status. Parallel with data collection, open coding was applied to the transcribed interviews. The Ottawa Model of Research Use (OMRU) framework, a comprehensive interdisciplinary model guide to promote implementation of research findings into healthcare practice, was used to categorize obtained codes and structure the barriers and facilitators into relevant themes for change.

Results

Thirteen interviews were conducted. Important barriers were the conflicting scientific evidence on (cost-)effectiveness of prehabilitation, the current inability to offer a personalized prehabilitation program, the complex logistic organization of the program, and the unawareness of (the importance of) a prehabilitation program among healthcare professionals and patients. Relevant facilitators were availability of program coordinators, availability of physician leadership, and involving skeptical colleagues in the implementation process from the start.

Conclusions

Important barriers to prehabilitation implementation are mainly related to the intervention being complex, relatively unknown and only evaluated in a research setting. Therefore, physicians’ leadership is needed to transform care towards more integration of personalized prehabilitation programs.

Implications for cancer survivors

By strengthening prehabilitation programs and evidence of their efficacy using these recommendations, it should be possible to enhance both the pre- and postoperative quality of life for colorectal cancer patients during survivorship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perioperative decline in functional capacity and condition in older patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) is not only caused by surgery itself, but also by the passive “waiting list period” before surgery [1]. The incidence and severity of decline in functional capacity could be reduced by prehabilitation [2, 3]. This is the process including assessments and interventions to establish a baseline functional level, identify impairments, and increase functional capacity between the time of cancer diagnosis and surgery [4]. Prehabilitation programs can be unimodal, focusing on optimizing physical condition solely, or multimodal, focusing on optimizing physical condition, nutritional status, and reduction of stress and anxiety [5]. Other components, such as smoking cessation, preoperative treatment of anemia, or medication reconciliation are also integrated as part of these programs. It is expected that a multimodal approach has synergistic effects resulting in better overall outcomes compared to unimodal approaches [6].

Prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery has shown promising results such as shorter hospital stay, reduction in postoperative complications, less functional decline, and improvements in health-related quality of life [7,8,9,10]. Therefore, prehabilitation for patients with colorectal cancer is being increasingly applied in hospitals.

However, prehabilitation is a complex intervention (as it comprises multiple components acting interdependently with evidence from heterogenous patient populations) and evaluation of such a complex intervention is difficult due to challenges in developing, identifying, documenting, and reproducing the intervention [11]. The complexity of prehabilitation and its evaluation are illustrated in the diversity in prehabilitation program designs (generally pragmatically and in line with what is achievable at the local setting) and differences in patient selection between the clinical trials. This leads to contradictory evidence regarding (cost-)effectiveness of prehabilitation [12,13,14,15,16] as well as to lack of generalizability of the results [17].

Because most clinical trials fail to evaluate their development and process phase, and almost no studies focus on implementation and effectiveness in daily practice, it is difficult to create a better understanding of the process of implementation of prehabilitation and the opportunities to improve. Qualitative research concerning the perspectives of professionals involved in prehabilitation in research settings as well as in daily care can help to understand how prehabilitation is delivered and which elements are perceived as important or problematic [17]. Previous qualitative studies already highlighted four key barriers for healthcare professionals to implementing a prehabilitation program: knowledge, resource, inconsistent practice, and poor patient engagement. However, there is a lack of documented facilitators [18]. Therefore, the aim of this interview study was to identify expected and perceived barriers and facilitators, in order to provide clinicians who want to implement prehabilitation in colorectal cancer surgery in their local setting, with practical recommendations.

Methods

Design

A qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with healthcare professionals involved in preoperative colorectal cancer surgery was performed.

Participants

Colorectal cancer surgeons, specialized (oncological) nurses, physical therapists, and dieticians were approached by email to participate in the interviews. At least two participants from each profession were purposefully selected. Eligible participants, both with and without prehabilitation experience, were identified based on a previous study of our group [19]. Prehabilitation was defined as a preoperative program with at least the aim of improving physical fitness and nutritional status.

Background information on the interviewees was collected regarding medical specialty, age, gender, years of working experience, and yes or no experiences with prehabilitation in colorectal cancer care. The total number of interviews needed was guided by thematic saturation. Thematic saturation was defined as the point where no new relevant knowledge from the data analysis was obtained. In practice, this was defined as the point where no new codes were assigned during open coding. The saturation was determined independently of the represented professions, which means that irrespective of the professional asked, no new codes were added [20].

Research team

The multidisciplinary research team consisted of nine researchers, most of whom were also clinicians. Two geriatricians (HM, MO), one internist-geriatrician (BM), one colorectal cancer surgeon (HW), one general practitioner with extensive qualitative research experience (MP). Two epidemiologists (ED, RM), one with research experience in cancer (p)rehabilitation (ED) and the other one in resilience management (RM). Two PhD students, conducting research in the field of prehabilitation and colorectal cancer, who are also medical doctor (TA, TH).

Data collection

The interviews were conducted between September 2019 and October 2020 at a place suitable for participants, or by telephone during the COVID-19 outbreak. Interviews lasted between 20 and 30 min. The interviews were independently conducted by one of three researchers (ED, TA, TH). A critical appraisal of previous literature on prehabilitation and implementation research was conducted to gain a comprehensive and adequate understanding of the subject [21]. These knowledge was used to compile the preliminary topic list in a meeting among members of the research group (Supplement 1). To confirm the coverage and relevance of the content, the topic list was adopted during the study whenever this was required based on preliminary data analysis.

All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data processing and analysis

Anonymized transcripts were imported into ATLAS.ti 8.4.20. After eight of in total thirteen interviews, scripts were independently coded by the first and second author using an open coding procedure [22].Codes were then compared and discussed until consensus was reached into a preliminary code book including potential barriers and facilitators. Each consecutive interview was coded directly afterwards, again independently by both the first and second author. After comparison, discussion, and consensus, the code book was adapted if needed. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and in consensus with the last author if necessary.

Thereafter, in a research team meeting, codes were compared to existing literature on models for dissemination and implementation research to determine the relationships between codes and to provide practical recommendations that are in line with clinical practice. The Ottawa Model of Research Use (OMRU) was selected to categorize the obtained codes for the purpose of practice recommendations [23]. The OMRU model was selected because it is a process model, specifically an action model, providing practical guidance in the planning and execution of implementation endeavors [24]. Using the OMRU model, key concepts as initial coding (sub)categories were identified. Codes that could not be categorized based on the model were organized in a new (sub)category [23].

The Ottawa Model of Research Use

The OMRU framework is an action-based model for studying implementation of healthcare innovations [24, 25]. The framework proposes to study six key components: innovation, environment, adopters, strategies for transferring evidence into practice, the use of evidence, and health-related and other outcomes of the process. These components are connected to each other through the process of evaluation [23]. The framework guides the assessment of potential barriers and facilitators to prehabilitation with regard to the innovation (prehabilitation), environment (hospital), adopters (health care professionals and patients), and if possible, also the strategies the interviewees identified for the implementation of prehabilitation. By incorporating specific barriers and facilitators into tailored strategies, the identified barriers can be overcome and facilitators enhanced. Also, suggestions are provided to monitor and evaluate the impact of implementation [23, 24].

Results

Thirteen interviews were conducted and included five surgeons (S1-5), three specialized nurses (SN1-3), three physical therapists (PT1-3), and two dieticians (D1-2) (Table 1). Interviewees worked in different hospitals, one academic hospital and four non-academic hospitals. Three interviewees had no experience with prehabilitation. The other interviewees had experience with prehabilitation, mainly in research setting, from less than 1 year to a maximum of 3 years.

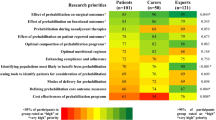

Tables 2 and 3 contain an overview of all coded barriers and facilitators, respectively. Also illustrative quotes with accompanying professional background of the interviewee are shown. We found no clusters of codes related to the professional background of the interviewees observed.

All but one of the obtained barriers and facilitators could be clustered into three categories of the assessment phase of the OMRU framework: the innovation itself, practice environment, and potential adopters. The one code that could not be categorized into the assessment phase was related to the monitor phase of the framework. In Table 4, identified barriers and facilitating factors are classified based on the systematic assessment phase of OMRU.

The innovation: prehabilitation

Barriers and facilitators of innovation by prehabilitation were mostly related to the relative (dis)advantages, compatibility, complexity and reinvention, observability (the degree to which the results of prehabilitation are visible to others), and trialability (the degree to which prehabilitation may be experimented with on a limited basis). Contradictory and low-quality scientific evidence for the (cost-)effectiveness of prehabilitation was frequently mentioned. Especially in combination with (high) immediate costs and no directly measurable or visible yields, it was often concluded that advantages of prehabilitation were unclear. Next, heterogeneity of the patient population together with the already high quality of colorectal cancer care surgery and low mortality and complication rates made it difficult to prove effectiveness on a group level. Furthermore, the perceived complexity of prehabilitation and differences in patients’ resilience and training opportunities (i.e., a “one size fits all” prehabilitation program would not work) was seen as barrier.

However, evidence concerning effectiveness of prehabilitation for both objective and patient-reported outcomes could facilitate program sustainability. Insights into effects on individual patient level are also important. Innovation could be further optimized by offering personal programs explicitly. Moreover, the personal experience of added value of prehabilitation was mentioned as an important facilitator, as prehabilitation aligns with patients’ perceived needs to improve self-reliance through prehabilitation rather than passively waiting for surgery.

Practice environment: the hospital

Barriers and facilitators in the hospital environment where prehabilitation is initiated were mostly related to physical structure, workload, available resources, personalities involved, and culture and beliefs. Identified barriers were mainly logistic. Some patients were not capable to visit the hospital frequently, while combining prehabilitation appointments with different healthcare professionals on a single day was also considered to be difficult because of different work activities of involved healthcare professionals. Also, the combination of counseling patients for prehabilitation and an additional multidisciplinary consultation was seen as time-consuming. The lack of structural program implementation evaluation in a team meeting to identify and resolve experienced problems was mentioned as well. Although the solution of an additional meeting is considered time-consuming, it was thought of as enhancing program sustainability and team building. Furthermore, the timing of surgery was identified as a logistic problem. The inflexible and rapidly changing operation room planning would often take priority over the prehabilitation program, resulting in an early termination of the prehabilitation program. At the same time, national quality indicators [26] state that treatment should take place within 6 weeks of diagnosis, making the time window for prehabilitation often (too) short.

Identified facilitators for the practice environment included combining patient appointments as it would not only lead to a decrease in the number of hospital visits for patients but could also ensure accessible contact between involved healthcare professionals. In addition, offering an intervention program close to home and implementation of digital tools were suggested options to reduce travel distances and facilitate patients’ compliance. Contact through multidisciplinary consultation in order to identify eligible patients and monitor a patients’ progress was identified as facilitator. To partially overcome the problem of time-consuming extra multidisciplinary consultations, it was stated that evaluation of individual patients may only be necessary in case of problems or deviation from the program. The availability of a dedicated nurse specialist who would coordinate the prehabilitation program and various program appointments was deemed important and the guarantee of financial support was seen as an important prerequisite. In order to overcome the timing of surgery, it was stated that it should be possible to delay the procedure if deemed necessary due to patient’s performance status. At last, prehabilitation should be introduced early in the diagnostic trajectory to create sufficient time for prehabilitation while still meeting the national guidelines for timely treatment after diagnosis.

Potential adopters: health care professionals and patients

Participating healthcare professionals identified themselves as well as patients as early adopters. Barriers and facilitators were related to attitudes, knowledge motivation, skills, and current practices. The unawareness of the importance and possibilities of a prehabilitation program by healthcare professionals was an important barrier. Including skeptic healthcare professionals early in the adoption phase of the innovation could facilitate and overcome this. With regard to patients, the dominating ideas about illness behavior were detrimental as they often believe that sedentary behavior is necessary when cancer is diagnosed. Also, patients believe that the tumor needs to be removed as soon as possible after diagnosis. However, according to the interviewees, patients are often unaware of the impact of surgery on their physical and mental condition and therefore, creating awareness of this impact is a facilitating factor. Patient’s gaining insights in their movement patterns and being able to set personal goals as well as including their social environment could all potentially facilitate adoption by patients. Also, group activities where patients would be able to exchange experiences and motivate peers were identified as a facilitating factor.

Transfer strategies: diffusion, dissemination, and implementation of prehabilitation

In the monitoring phase, an ambassador, who could persuade, enthuse, and unite coworkers, is necessary for the diffusion, dissemination, and implementation of prehabilitation in the hospital for the long term. This ambassador is preferably a medical specialist.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore barriers and facilitators regarding the implementation of prehabilitation in colorectal cancer surgery as expected and perceived by involved healthcare professionals. Important barriers included the conflicting scientific evidence on (cost-)effectiveness of prehabilitation, the inability of patients to follow a predefined hospital-based prehabilitation program (due to lack of personalized programs or inflexibility of “prescribed” prehabilitation) and the complex logistic organization of the program. Besides, unawareness of (importance of) the prehabilitation program among both healthcare professionals and patients and incorrect ideas of patients about what is important in the preoperative phase were mentioned as serious barriers. Important facilitators were the ability to offer a personalized prehabilitation program for each individual, availability of a program coordinator, and involving skeptical colleagues from the start of the implementation. For transferring prehabilitation within the practice environment, an ambassador was deemed as an important facilitator.

To implement an innovation such as prehabilitation in clinical practice, an individualized program with regard to content, duration, and setting is needed [27]. In order to create more patient-centeredness, questions including what, when, where, who, and why should be taken into account while developing future prehabilitation programs [28]. Additionally, performing a comprehensive geriatric assessment preoperatively can be useful to select patients and increase both adherence and effectiveness of prehabilitation [29].

Furthermore, implementation of prehabilitation requires adjustments in the hospital as practice environment. Local adjustments in the organization of preoperative colorectal cancer care pathways are needed to create availability of dedicated resources and time for involved healthcare professionals. The presence of a program coordinator, for example an oncology nurse, can facilitate effective implementation [30, 31]. This program coordinator can overview the program and signals arising problems on both organizational and patient level. Costs of the additional resources for lifestyle-initiated programs must be guaranteed from the start of implementation, if prehabilitation is indeed (cost-)effective [32]. Financing of these costs should be considered on both hospital and national level [33].

Another adjustment in the organization of preoperative colorectal cancer care should be the possibility to lengthen the time interval between operation indication and surgery, which could serve as a protective time interval to battle negative oncological outcomes [34]. As the mandatory standards [26] and operation room planning currently determine the time between indication and actual surgery, it should rather be the surgeon determining (extended) time until surgery based on the patients’ physical condition and nutritional status and the ability to improve this by prehabilitation.

Because healthcare professionals and patients are not passive recipients of prehabilitation, implementation and adoption of the program should be seen as a transition process rather than an event. In other words, it is important that adopters in the preadoption stage are aware of the innovation. This implies that what prehabilitation does, how to use it, and how it affects the adopter personally should be incorporated [35]. Moreover, skeptics in the surgical pathway need to be included in the prehabilitation team and early in the adoption phase to convince them of the potential merits of prehabilitation and to ensure appropriate information provision towards patients [27, 36].

If potential benefits of prehabilitation remain unclear for recipients, transforming care towards more integration is difficult, and consequently, demonstration of efficacy will fail due to low program adherence. Physicians in particular are the principal players to break this vicious circle by either supporting or opposing successful transformative efforts [37]. Therefore, physicians’ leadership is essential to facilitate diffusion, dissemination, and implementation of prehabilitation both on micro (clinical integration), meso- (professional and organizational integration), and macro- (system integration) levels [38].

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study performed by a multidisciplinary research team with healthcare professionals involved in preoperative colorectal cancer care from different disciplines and hospitals. This provided important insights regarding perceived issues and promotors by implementing prehabilitation from clinical experiences. Although the number of hospitals which have implemented prehabilitation is limited in the Netherlands, many barriers and facilitators for local implementation of prehabilitation in colorectal cancer surgery in research setting were mentioned by multiple healthcare professionals, and thematic saturation was reached as planned. Above, at least theoretical generalizability has been achieved, as all mentioned barriers and facilitators could be placed in the selected framework [39]. As prehabilitation was not part of daily care yet in participating hospitals, implementation regarding perceived barriers and facilitators in daily care instead of a research setting could not be elaborated on.

Previous studies, interviewing patients, highlighted already the importance of appropriate information provision and an accessible personalized prehabilitation program [27, 28, 36, 40]. Nevertheless, the perspective of healthcare professionals on barriers and facilitators at patient level is also of added value [18].

In this study, open coding was independently performed by the first and second author and differences in outcomes were discussed during a group meeting where barriers and facilitators were classified as well. By using direct content analysis, the data collection can become biased by emphasizing this theory [41]. However, the theoretical framework was selected after conducting and coding interviews and therefore overemphasis of the theoretical framework is expected to be minimal. In addition, the use of the OMRU framework guided the discussion of findings, allowing for more explicit recommendations.

Future research

Although clear and unambiguous evidence of effectiveness is necessary, this will be difficult to obtain for a complex and environment-dependent intervention like prehabilitation, especially if the implementation rate is unsatisfactory. Consequently, individual randomized clinical trials, representing the reference standard, may not be applicable [42]. Instead, pragmatic trials, producing results that can be generalized and applied in routine practice setting, are more appropriate [43]. It would be useful to implement prehabilitation in phases, parallel to monitoring the adoption process and ensuring data-driven continuous improvement [23].

Future trials should perform a preplanned process evaluation including patient experience alongside the effect evaluation to assess fidelity and quality of implementation, clarify causal mechanisms, and identify contextual factors associated with variation in outcomes, resulting in more efficient adaptation, development, and implementation of prehabilitation [44, 45]. A preplanned process evaluation could for example make clear which patient group benefits the most of prehabilitation, especially because prehabilitation programs should be tailor-made and benefits are predominantly patient-specific. Besides, the focus on the process and context of prehabilitation could generate additional hypotheses about mechanisms of success or failure [35]. Furthermore, collaboration between local initiatives and the use of standardized outcome instruments should be emphasized [46].

When evidence regarding effectiveness of prehabilitation is properly displayed, this could persuade skeptics and facilitate the acquisition of financial support, to create a broad-based willingness to implement prehabilitation by both healthcare organizations and healthcare professionals [35]. Future prehabilitation programs should also optimize feasibility, e.g., deliver prehabilitation programs close to home and use digital tools, which were mentioned in this study as facilitators. Finally, the benefits of a longer prehabilitation program, combined with rehabilitation program after surgery, should be further investigated.

In conclusion, important barriers to prehabilitation implementation are mainly related to the intervention being complex, relatively unknown and only minimally evaluated in research settings. The need for clear and unambiguous evidence is however at odds with implementation issues, even in research context, due to negative attitudes of skeptical professionals towards prehabilitation, limited organizational flexibility (e.g., inability to combine appointments), conflicting guidelines (e.g., strict operation timeframe), and patient cognitions (e.g., need for sedentary behavior in illness). Therefore, physicians’ leadership is needed to transform care towards more integration of prehabilitation on micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. The implementation should be phased, with the possibility to adapt the intervention to the variety of real-life contexts and to test its effectiveness in daily practice. Above, the possibility to offer a personalized prehabilitation program will increase willingness to participate in both patients and professionals. By strengthening prehabilitation programs and evidence of their efficacy using these recommendations, it should be possible to enhance both the pre- and postoperative quality of life for future colorectal cancer patients.

Data availability

The data and material collected for this article are available on request.

Code availability

No applicable.

References

Hulzebos EH, van Meeteren NL (2016) Making the elderly fit for surgery. Br J Surg 103(2):e12–e15. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10033

Silver JK, Baima J (2013) Cancer prehabilitation: an opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 92(8):715–727. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31829b4afe

Hughes MJ et al (2019) Prehabilitation before major abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg 43(7):1661–1668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-04950-y

Minnella EM, Carli F (2018) Prehabilitation and functional recovery for colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 44(7):919–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.04.016

Carli F et al (2017) Surgical prehabilitation in patients with cancer: state-of-the-science and recommendations for future research from a panel of subject matter experts. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 28(1):49–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2016.09.002

López Rodríguez-Arias F et al (2020) A narrative review about prehabilitation in surgery: current situation and future perspectives. Cirugía Española (English Edition) 98(4):178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cireng.2020.03.014

Carli F, Zavorsky GS (2005) Optimizing functional exercise capacity in the elderly surgical population. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 8(1):23–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200501000-00005

Barberan-Garcia A et al (2018) Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg 267(1):50–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002293

Berkel AEM et al (2022) Effects of community-based exercise prehabilitation for patients scheduled for colorectal surgery with high risk for postoperative complications: results of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 275(2):299–306. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000004702

Heger P et al (2020) A systematic review and meta-analysis of physical exercise prehabilitation in major abdominal surgery (PROSPERO 2017 CRD42017080366). J Gastrointest Surg 24(6):1375–1385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04287-w

Campbell M et al (2000) Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 321(7262):694–696. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694

Hijazi Y, Gondal U, Aziz O (2017) A systematic review of prehabilitation programs in abdominal cancer surgery. Int J Surg 39:156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.111

Daniels SL et al (2020) Prehabilitation in elective abdominal cancer surgery in older patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJS open 4(6):1022–1041. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs5.50347

Carli F et al (2020) Effect of multimodal prehabilitation vs postoperative rehabilitation on 30-day postoperative complications for frail patients undergoing resection of colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 155(3):233–242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5474

Fulop A et al (2021) The effect of trimodal prehabilitation on the physical and psychological health of patients undergoing colorectal surgery: a randomised clinical trial. Anaesthesia 76(1):82–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15215

West MA, Jack S, Grocott MPW (2021) Prehabilitation before surgery: is it for all patients? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2021.01.001

Bradley F et al (1999) Development and evaluation of complex interventions in health services research: case study of the Southampton heart integrated care project (SHIP). BMJ 318(7185):711–715. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7185.711

Chapman ORMTO (2021) Barriers and facilitators for healthcare professionals to implementing a prehabilitation programme review of the literature. J Cancer Rehab 4(86):90

Heil TC et al (2021) Technical efficiency evaluation of colorectal cancer care for older patients in Dutch hospitals. PLoS ONE 16(12):e0260870. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260870.10.1371/journal.pone.0260870

Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD (2015) sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res 26(13):1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

Kallio H et al (2016) Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs 72(12):2954–2965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13031

Green J, Thorogood N (2018) Qualitative methods for health research. Sage, Los Angeles

Logan JO, Graham ID (1998) Toward a comprehensive interdisciplinary model of health care research use. Sci Commun 20(2):227–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547098020002004

Nilsen P (2015) Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci 10(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

Tabak RG et al (2012) Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med 43(3):337–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024

Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing (2021) Indicatorengids Colorectaal carcinoom DCRA verslagjaar 2021. https://www.zorginzicht.nl/binaries/content/assets/zorginzicht/kwaliteitsinstrumenten/indicatorengids-colorectaal-carcinoom-dcra-verslagjaar-2021.pdf

Ferreira V et al (2018) Maximizing patient adherence to prehabilitation: what do the patients say? Support Care Cancer 26(8):2717–2723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4109-1

Beck A, et al. (2020) Investigating the experiences, thoughts, and feelings underlying and influencing prehabilitation among cancer patients: a qualitative perspective on the what, when, where, who, and why. Disabil Rehabil 44(2):202–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1762770

Saur NM et al (2017) Attitudes of surgeons toward elderly cancer patients: a survey from the SIOG surgical task force. Visceral Medicine 33(4):262–266. https://doi.org/10.1159/000477641

Woiceshyn J, Blades K, Pendharkar SR (2017) Integrated versus fragmented implementation of complex innovations in acute health care. Health Care Manage Rev 42(1):76–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/hmr.0000000000000092

Lukez A, Baima J (2020) The role and scope of prehabilitation in cancer care. Semin Oncol Nurs 36(1):150976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2019.150976

Barberan-Garcia A et al (2019) Post-discharge impact and cost-consequence analysis of prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery: secondary results from a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 123(4):450–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.05.032

Kroes ME, et al. (2007) Van preventie verzekerd. CVZ: Diemen. https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publicaties/rapport/2007/07/16/van-preventie-verzekerd

Molenaar CJL, Winter DC, Slooter GD (2021) Contradictory guidelines for colorectal cancer treatment intervals. Lancet Oncol 22(2):167–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30738-5

Greenhalgh T et al (2004) Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 82(4):581–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

Agasi-Idenburg CS et al (2020) “I am busy surviving” - views about physical exercise in older adults scheduled for colorectal cancer surgery. J Geriatr Oncol 11(3):444–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.05.001

Best A et al (2012) Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Q 90(3):421–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00670.x

Nieuwboer MS et al (2019) Clinical leadership and integrated primary care a systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract 25(1):7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2018.1515907

Carminati L (2018) Generalizability in qualitative research: a tale of two traditions. Qual Health Res 28(13):2094–2101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318788379

Ijsbrandy C et al (2019) Implementing physical activity programs for patients with cancer in current practice: patients’ experienced barriers and facilitators. J Cancer Surviv 13(5):703–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00789-3

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Minary L et al (2019) Which design to evaluate complex interventions? Toward a methodological framework through a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 19(1):92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0736-6

Patsopoulos NA (2011) A pragmatic view on pragmatic trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 13(2):217–24. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.2/npatsopoulos

Reelick MF et al (2011) How to perform a preplanned process evaluation for complex interventions in geriatric medicine: exemplified with the process evaluation of a complex falls-prevention program for community-dwelling frail older fallers. J Am Med Dir Assoc 12(5):331–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.006

Moore GF et al (2015) Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ : British Medical Journal 350:h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

Bruns ERJ et al (2019) Improving outcomes in oncological colorectal surgery by prehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 98(3):231–238. https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000001025

Funding

Grant number: 80–85009-98–1003. Zorgevaluatie Leading the Change. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and study design: T. C. Heil, T. E. Argillander, R. J. F. Melis, H. A. A. M. Maas, M. G. M. Olde Rikkert, J. H. W. de Wilt, B. C. van Munster, M. Perry. Data collection: T. C. Heil, E. J. M. Driessen, T. E. Argillander. Data analysis and interpretation: T. C. Heil, E. J. M. Driessen, R. J. F. Melis, H. A. A. M. Maas, M. G. M. Olde Rikkert, J. H. W. de Wilt, B. C. van Munster, M. Perry. Writing original draft: T. C. Heil, E. J. M. Driessen, M. Perry. Critical revision original draft: T. E. Argillander, R. J. F. Melis, H. A. A. M. Maas, M. G. M. Olde Rikkert, J. H. W. de Wilt, B. C. van Munster.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This qualitative research did not cover topics of sensitive personal nature and therefore did not require approval of an ethics committee as included in the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (Wet Medisch‐Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek met Mensen, 1998).

Consent to participate

All healthcare professionals received written information about the goals and procedures of the study. Prior to audio-recording of the interviews, verbal consent was obtained. Retrieved information from healthcare professionals was handled confidentially and analyzed anonymously.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heil, T.C., Driessen, E.J.M., Argillander, T.E. et al. Implementation of prehabilitation in colorectal cancer surgery: qualitative research on how to strengthen facilitators and overcome barriers. Support Care Cancer 30, 7373–7386 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07144-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07144-w