Abstract

Purpose

To examine the acceptability of the methods used to evaluate Coping-Together, one of the first self-directed coping skill intervention for couples facing cancer, and to collect preliminary efficacy data.

Methods

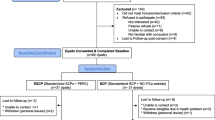

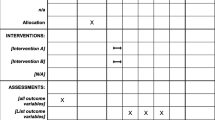

Forty-two couples, randomized to a minimal ethical care (MEC) condition or to Coping-Together, completed a survey at baseline and 2 months after, a cost diary, and a process evaluation phone interview.

Results

One hundred seventy patients were referred to the study. However, 57 couples did not meet all eligibility criteria, and 51 refused study participation. On average, two to three couples were randomized per month, and on average it took 26 days to enrol a couple in the study. Two couples withdrew from MEC, none from Coping-Together. Only 44 % of the cost diaries were completed, and 55 % of patients and 60 % of partners found the surveys too long, and this despite the follow-up survey being five pages shorter than the baseline one. Trends in favor of Coping-Together were noted for both patients and their partners.

Conclusions

This study identified the challenges of conducting dyadic research, and a number of suggestions were put forward for future studies, including to question whether distress screening was necessary and what kind of control group might be more appropriate in future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Resendes LA, McCorkle R (2006) Spousal responses to prostate cancer: an intergrative review. Cancer Invest 24:192–198

Lambert S, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C, Stacey F (2013) Walking a mile in their shoes: anxiety and depression among caregivers of cancer survivors at six and 12 months post-diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 21:75–85

Lambert SD, Jones B, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C (2012) Distressed partners and caregivers do not recover easily: adjustment trajectories among partners and caregivers of cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med 44:225–235

Boyes A, Girgis A, D'Este C, Zucca A (2011) Flourishing or floundering? Prevalence and correlates of anxiety and depression among a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors 6 months after diagnosis. J Affect Disord 135:184–192

Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW (2010) Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Cancer J Clin 60:317–339

Regan T, Lambert SD, Girgis A, Kelly B, Turner J, Kayser K (2012) Do couple-based interventions make a difference for couples affected by cancer? BMC Cancer 12:279

Scott JL, Halford KW, Ward BG (2004) United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 72:1122–1135

Regan T, Lambert S, Kelly B (2013) Uptake and attrition in couple-based interventions for cancer: perspectives from the literature. Psychooncology 22:2639–2647

Jacobsen PB, Meade CD, Stein KD, Chirikos TN, Small BJ, Ruckdeschel JC (2002) Efficacy and costs of two forms of stress management training for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 20:2851–2862

Beatty L, Koczwara B, Rice J, Wade T (2010) A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effects of a self-help workbook intervention on distress, coping and QOL after breast cancer diagnosis. Med J Aust 193(5 Suppl):S68–S73

Lambert SD, Girgis A, Turner J, Regan T, Candler H, Britton B et al (2013) “"You need something like this to give you guidelines on what to do”: patients’ and partners’ use and perceptions of a self-directed, coping skills training resource. Support Care Cancer 21:3451–3460

Lambert SD, Girgis A, Turner J, McElduff P, Kayser K, Vallentine P (2012) A pilot randomized controlled trial of the feasibility of a self-directed coping skills intervention for couples facing prostate cancer: rationale and design. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10:119

Altman D, Schulz K, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D et al (2001) The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 134:663–694

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2012) Distress management clinical practice guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F et al (2005) Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients: a multicenter evaluation of the distress thermometer. Cancer 103:1494–1502

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiat Scand 67:361–370

Bjelland I, Dahl A, Haug T, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52:69–77

Weiss DS, Marmar CR (1997) The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM (eds) Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. Guilford, New York, pp 399–411

Manne S, Ostroff J, Fox K, Grana G, Winkel G (2009) Cognitive and social processes predicting partner psychological adaptation to early stage breast cancer. Br J Health Psychol 14:49–68

Richardson J, Khan M, Iezzi A, Sinha K, Mihalopoulos C, Herrman H, et al. (2009) The AQoL-8D (PsyQoL) MAU Instrument: overview September 2009 Research paper39, Centre for Health Economics

Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner H, Friedland J, Cox C (1999) The Caregiver Quality of Life Index–Cancer (CQOLC) scale: development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res 8:55–63

Busby DM, Christensen C, Crane DR, Larson JH (1995) A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. J Marital Fam Ther 21:289–308

Manne SL, Norton TR, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G (2007) Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: the moderating role of relationship satisfaction. J Fam Psychol 21:380–388

Kessler TA (1998) The Cognitive Appraisal of Health Scale: development of psychometric evaluation. Res Nurs Health 21:73–82

Mishel MH (1981) The measurement of uncertainty in illness. Nurs Res 30:258–263

Lambert SD, Yoon H, Ellis K, Northouse L (2015) Measuring appraisal during advanced cancer: psychometric testing of the Appraisal of Caregiving Scale. Patient Educ Couns

Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, Montie JE, Sandler HM, Forman JD et al (2007) Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer 110:2809–2818

Lewis FM (1996) Family home visitation study final report. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health., Bethesda

Wolf MS, Chang CH, Davis T, Makoul G (2005) Development and validation of the Communication and Attitudinal Self-Efficacy Scale for Cancer (CASE-cancer). Patient Educ Couns 57:333–341

Carver CS (1997) You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the Brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 4:92–100

Cooper C, Katona C, Orrell M, Livingston G (2008) Coping strategies, anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23:929–936

Feldman BN, Broussard CA (2005) The influence of relational factors on men’s adjustment to their partners’ newly-diagnosed breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 23:23–43

Bodenmann G (2008) Dyadisches Coping Inventar: Testmanual [Dyadic Coping Inventory: Test Manual]. Huber, Bern

Girgis A, Shih STF, Lambert SD, Mihalopoulos C (2011) My Cancer Care Cost Diary. University of New South Wales & Deakin University

Northouse L, Rosset T, Phillips L, Mood D, Schafenacker A, Kershaw T (2006) Research with families facing cancer: the challenges of accrual and retention. Res Nurs Health 29:199–211

Hacking B, Wallace L, Scott S, Kosmala-Anderson J, Belkora J, McNeill A (2013) Testing the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a ‘decision navigation’ intervention for early stage prostate cancer patients in Scotland—a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology 22:1017–1024

Berglund G, Petersson LM, Eriksson KC, Wallenius I, Roshanai A, Nordin KM et al (2007) “Between Men”: a psychosocial rehabilitation programme for men with prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 46:83–89

Lambert SD, Pallant J, Clover K, Britton B, King M, Carter G (2014) Using Rasch analysis to examine the distress thermometer’s cut-off scores among a mixed group of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res 23(8):23, 2257–2265

Linden W, Satin JR (2007) Avoidable pitfalls in behavioral medicine outcome research. Ann Behav Med 33:143–147

Schneider S, Moyer A, Knapp-Oliver S, Sohl S, Cannella D, Targhetta V (2010) Pre-intervention distress moderates the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med 33:1–14

Lambert SD, Kelly B, Boyes A, Cameron A, Adams C, Proietto A et al (2014) Insights into preferences for psycho-oncology services among women with gynaecologic cancer following distress screening. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 12:899–906

van Scheppingen C, Schroevers MJ, Pool G, Smink A, Mul VE, Coyne JC et al (2013) Is implementing screening for distress an efficient means to recruit patients to a psychological intervention trial? Psychooncology 23:516–523

Porter SR (2004) Raising response rates: what works? New Dir Inst Res 2004:5–21

Sahlqvist S, Song Y, Bull F, Adams E, Preston J, Ogilvie D et al (2011) Effect of questionnaire length, personalisation and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol 11:62

Kalantar JS, Talley NJ (1999) The effects of lottery incentive and length of questionnaire on health survey response rates: a randomized study. J Clin Epidemiol 52:1117–1122

Mond JM, Rodgers B, Hay PJ, Owen C, Beumont PJ (2004) Mode of delivery, but not questionnaire length, affected response in an epidemiological study of eating-disordered behavior. J Clin Epidemiol 57:1167–1171

Lavrakas PJ (2011) Encyclopedia of survey research methods. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks

van den Brink M, van den Hout WB, Stiggelbout AM, Putter H, van de Velde CJH, Kievit J (2005) Self-reports of health-care utilization: diary or questionnaire? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 21:298–304

Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J (2005) Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980–2003). Patient Educ Couns 57:250–261

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a Clinical Oncological Society of Australia/Sanofi Aventis Advancing the Care for Prostate Care Patients Research Grant 2010.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lambert, S.D., McElduff, P., Girgis, A. et al. A pilot, multisite, randomized controlled trial of a self-directed coping skills training intervention for couples facing prostate cancer: accrual, retention, and data collection issues. Support Care Cancer 24, 711–722 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2833-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2833-3