Abstract

One of the challenges in computational fluid–structure interaction (FSI) analysis of spacecraft parachutes is the “geometric porosity,” a design feature created by the hundreds of gaps and slits that the flow goes through. Because FSI analysis with resolved geometric porosity would be exceedingly time-consuming, accurate geometric-porosity modeling becomes essential. The geometric-porosity model introduced earlier in conjunction with the space–time FSI method enabled successful computational analysis and design studies of the Orion spacecraft parachutes in the incompressible-flow regime. Recently, porosity models and ST computational methods were introduced, in the context of finite element discretization, for compressible-flow aerodynamics of parachutes with geometric porosity. The key new component of the ST computational framework was the compressible-flow ST slip interface method, introduced in conjunction with the compressible-flow ST SUPG method. Here, we integrate these porosity models and ST computational methods with isogeometric discretization. We use quadratic NURBS basis functions in the computations reported. This gives us a parachute shape that is smoother than what we get from a typical finite element discretization. In the flow analysis, the combination of the ST framework, NURBS basis functions, and the SUPG stabilization assures superior computational accuracy. The computations we present for a drogue parachute show the effectiveness of the porosity models, ST computational methods, and the integration with isogeometric discretization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Computational fluid–structure interaction (FSI) analysis of spacecraft parachutes involves a number of challenges beyond those in a typical FSI analysis (see [1, 2] and references therein, and [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]), including some that are formidable. The Deforming-Spatial-Domain/Stabilized Space–Time (DSD/SST) method [2, 11,12,13,14,15] has been serving as the core computational technology in addressing these challenges, and special ST methods introduced in conjunction with these core technologies have brought spacecraft parachute FSI analysis to a new level (see [1, 2] and references therein, and [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]). The core and special ST methods enabled successful computational analysis and design studies of the Orion spacecraft parachutes (see [1, 2] and references therein, and [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]).

Spacecraft parachute analysis with the ST computational methods started in 2007. The studies conducted in the first five years can be found in [1, 2] and references therein. The aspects of spacecraft parachutes studied in the last five years include “disreefing” [3, 6], spacecraft cover separation [4], parachute designs with modified “geometric porosity” [3, 5], gore curvature calculation [7], aerodynamic-moment calculation [8], drogue parachutes [6, 9], and compressible-flow parachute aerodynamics [10].

The DSD/SST method was introduced in [11, 16, 17], intended for computation of flows with moving boundaries and interfaces (MBI), including FSI. Because it functions as a moving-mesh method in MBI computations, the fluid mechanics mesh follows the fluid–solid interfaces, enabling mesh-resolution control and accurate flow representation near those interfaces. What made the original DSD/SST method “stabilized” were the Streamline-Upwind/Petrov–Galerkin (SUPG) [18] and Pressure-Stabilizing/Petrov-Galerkin (PSPG) [11] components, and for that the method is now also called “ST-SUPS.” The ST Variational Multiscale (ST-VMS) method [14, 15] is the VMS version of the DSD/SST method, with the VMS components coming from the residual-based VMS (RBVMS) method [19,20,21,22].

The RBVMS method has been shown to have good turbulence modeling features, including in the context of the ALE-VMS method [2, 23,24,25,26,27], which is the VMS version of the Arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian (ALE) finite element method [28]. The ALE method is a more commonly used moving-mesh method. To increase their scope and accuracy, the ALE-VMS and RBVMS methods are often supplemented with special methods, such as those for weakly enforced no-slip boundary condition [29,30,31], “sliding interfaces” [32, 33] and backflow stabilization [34]. The first increases accuracy in turbulent flows with active walls, the second enables application of the ALE-VMS method to flow computations with solid surfaces in fast relative motion, and the third prevents divergence due to possible reverse flow at the outflow boundaries. The RBVMS and ALE-VMS methods have been successfully used for different types of FSI, MBI and fluid mechanics problems. The classes of problems include wind-turbine aerodynamics and FSI [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], more specifically, vertical-axis wind turbines [43, 44], floating wind turbines [45], wind turbines in atmospheric boundary layers [46], and fatigue-damage in wind-turbine blades [47], patient-specific cardiovascular fluid mechanics and FSI [23, 48,49,50,51,52,53], biomedical-device FSI [54,55,56,57,58,59], ship hydrodynamics with free-surface flow and fluid–object interaction [60, 61], hydrodynamics and FSI of a hydraulic arresting gear [62, 63], hydrodynamics of tidal-stream turbines with free-surface flow [64], and bioinspired FSI for marine propulsion [65, 66].

The ST-VMS method, because of the source of its VMS components, also has good turbulence modeling features, and the ST-SUPS method, which is a reduced version of the ST-VMS method, can quite often perform reasonably well. The ST-SUPS and ST-VMS methods, because of their ST accuracy features (see [14, 15]), would be desirable also in computations that do not involve any MBI. They have been successfully used for different classes of FSI, MBI and fluid mechanics problems. The classes of problems include spacecraft parachute analysis for the main parachutes [1,2,3, 5, 8], cover-separation parachutes [4] and the drogue parachutes [6, 7, 9], wind-turbine aerodynamics for horizontal-axis wind-turbine rotors [2, 35, 67, 68], full horizontal-axis wind turbines [41, 69,70,71] and vertical-axis wind turbines [72], flapping-wing aerodynamics for an actual locust [2, 73,74,75], bioinspired MAVs [70, 71, 76, 77] and wing-clapping [78, 79], blood flow analysis of cerebral aneurysms [70, 80], stent-blocked aneurysms [80,81,82], aortas [83, 84] and heart valves [71, 78, 84,85,86,87], spacecraft aerodynamics [4, 88], thermo-fluid analysis of ground vehicles and their tires [89], thermo-fluid analysis of disk brakes [90], flow-driven string dynamics in turbomachinery [91], flow analysis of turbocharger turbines [92,93,94], flow around tires with road contact and deformation [95, 96], ram-air parachutes [97], and compressible-flow parachute aerodynamics [10].

The core and special ST computational methods have been playing by far the most prevalent role in FSI analysis of spacecraft parachutes (as documented in [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] and references therein). Actually, parachute FSI analysis in 3D with the ST computational methods started about 10 years earlier than the FSI analysis of spacecraft parachutes. In that earlier 10-year period, the ST computational methods played the most prevalent role in FSI analysis of various types of personnel and cargo parachutes (as documented in the earlier references cited in [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]). However, computational FSI analysis of spacecraft parachutes involves challenges not only beyond those in a typical FSI analysis, but also beyond those in parachute FSI analysis, and even beyond those in large-parachute FSI analysis. One of those challenges is the “geometric porosity,” a design feature created by the hundreds of gaps and slits that the flow goes through. Because FSI analysis with resolved geometric porosity would require resolving the flow that goes through the hundreds of gaps and slits as they change their shapes during the computation, it would be exceedingly time-consuming. That makes accurate geometric-porosity modeling essential. One of the special methods targeting spacecraft parachutes, the Homogenized Modeling of Geometric Porosity (HMGP) [3, 98], was introduced to address this computational challenge. The HMGP was a key contributor to successful computational analysis and design studies of the Orion spacecraft parachutes since 2007 (see [1, 2] and references therein, and [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]).

Until recently, ST computational analysis of spacecraft parachutes focused on the Orion spacecraft main parachutes, which are the parachutes used for landing, in the incompressible-flow regime, which is where the main parachutes operate. At the higher-altitudes, drogue parachutes will be used, and that will mostly be in the compressible-flow regime. These parachutes have a ribbon construction and 24 gores, with 52 ribbons in each gore, where a gore is the slice of the parachute canopy between two radial reinforcement cables running from the parachute vent to the skirt. This construction results in hundreds of gaps that the flow goes through, creating a geometric-porosity challenge similar to the one faced in FSI analysis of the main parachutes. Furthermore, there are three wider gaps along the gore, created by removing ribbons. Drogue FSI computations with the ST computational methods were first presented in [6, 7, 9], for the incompressible-flow part of the flight envelope.

Geometric-porosity models and ST computational methods for compressible-flow aerodynamics of spacecraft parachutes were introduced recently [10] in the context of finite element discretization. The key new component of the ST computational framework was the compressible-flow ST Slip Interface (ST-SI) method, introduced in conjunction with the compressible-flow ST SUPG method.

The compressible-flow ST SUPG method is essentially the same as the compressible-flow DSD/SST method, but without necessarily implying a mesh motion. The compressible-flow DSD/SST method is a straightforward mixture of the DSD/SST concept and the compressible-flow SUPG method. The first 3D computation with the compressible-flow DSD/SST method was reported in 1996 [99] for two high-speed trains passing each other in a tunnel. The interested reader can find in [10] a summary of when and in what context the compressible-flow SUPG method was introduced [100,101,102], how it evolved with the addition of a shock-capturing term [103, 104] and with new stabilization and shock-capturing parameters [105,106,107], and what test computations [108,109,110] were reported.

The ST-SI method [72] was introduced to retain the desirable moving-mesh features of the ST-VMS method (and its reduced version, ST-SUPS) when we have spinning solid surfaces, such as a turbine rotor or a tire. With the ST-SI method, the mesh covering the spinning solid surface spins with it and we retain the high-resolution representation of the boundary layers. The starting point in the development of the ST-SI method was the version of the ALE-VMS method designed for computations with sliding interfaces [32, 33]. In the ST-SI method, interface terms similar to those in the ALE-VMS version are added to the ST-VMS formulation to account for the compatibility conditions for the velocity and stress. The SI between the spinning mesh and the rest of the mesh accurately connects the two sides. An ST-SI version where the SI is between fluid and solid domains with weakly-imposed Dirichlet boundary conditions for the fluid was also presented in [72]. The ST-SI method introduced in [90] for the coupled incompressible-flow and thermal-transport equations addresses the challenge involved in high-resolution representation of the thermo-fluid boundary layers near spinning solid surfaces. These ST-SI methods have been successfully applied to aerodynamic analysis of vertical-axis wind turbines [72], thermo-fluid analysis of disk brakes [90], flow-driven string dynamics in turbomachinery [91], flow analysis of turbocharger turbines [92,93,94], flow around tires with road contact and deformation [95, 96], aerodynamic analysis of ram-air parachutes [97], and heart valve flow analysis [84, 86, 87].

The ST-SI methods have additional desirable features. The SI provides mesh generation flexibility in a general context by accurately connecting nonmatching meshes. This feature was used in the flow analysis of a heart valve [84, 87] and a turbocharger turbine [92,93,94]. This type of mesh generation flexibility is especially valuable in complex-geometry flow computations with isogeometric discretization, removing the matching requirement between the NURBS patches without loss of accuracy (see [93, 94]). In another version of the ST-SI method presented in [72], the SI is between a thin porous structure and the fluid on its two sides. With this, the fabric porosity is dealt with in a fashion consistent with how the standard two-sided SIs are dealt with and how the Dirichlet conditions are enforced weakly. Furthermore, this version of the ST-SI method enables handling thin structures that have T-junctions. This method has been successfully used in incompressible-flow aerodynamic analysis of ram-air parachutes with fabric porosity [97].

The compressible-flow ST-SI methods were introduced in [10], including the version where the SI is between a thin porous structure and the fluid on its two sides. Compressible-flow porosity models were also introduced in [10]. These, together with the compressible-flow ST SUPG method, extended the ST computational analysis range to compressible-flow aerodynamics of parachutes with fabric and geometric porosities. That enabled successful ST computational flow analysis of the Orion spacecraft drogue parachute in the compressible-flow regime [10]. The computations were in the context of finite element discretization.

The ST Isogeometric Analysis (ST-IGA), which is the integration of the ST methods with isogeometric discretization, was introduced in [14], inspired by the success of using IGA basis functions in space [23, 32, 48, 111]. First computations with the ST-VMS method and ST-IGA were reported in [14] in a 2D context, with IGA basis functions in space for flow past an airfoil and in both space and time for the advection equation. The stability and accuracy analysis given [14] for the advection equation showed that using higher-order basis functions in time would be essential in getting full benefit out of using higher-order basis functions in space.

In the early stages of the ST-IGA, the emphasis was on IGA basis functions in time. As pointed out in [14, 15] and demonstrated in [73, 74, 76], higher-order NURBS basis functions in time provide a more accurate representation of the motion of the solid surfaces and a mesh motion consistent with that. They also provide more efficiency in temporal representation of the motion and deformation of the volume meshes, and better efficiency in remeshing. That is how the ST/NURBS Mesh Update Method (STNMUM) was introduced and demonstrated in [73, 74, 76]. The name “STNMUM” was given in [69]. The STNMUM has a wide scope that includes spinning solid surfaces. With the spinning motion represented by quadratic NURBS basis functions in time, and with sufficient number of temporal patches for a full rotation, the circular paths are represented exactly, and a “secondary mapping” [2, 14, 15, 73] enables also specifying a constant angular velocity for invariant speeds along the paths. The ST framework and NURBS in time also enable, with the “ST-C” method, extracting a continuous representation from the computed data and, in large-scale computations, efficient data compression [89,90,91, 112]. The STNMUM and desirable features of the ST-IGA with IGA basis functions in time have been demonstrated in many 3D computations. The classes of problems solved are flapping-wing aerodynamics for an actual locust [2, 73,74,75], bioinspired MAVs [70, 71, 76, 77] and wing-clapping [78, 79], separation aerodynamics of spacecraft [4], aerodynamics of horizontal-axis [41, 69,70,71] and vertical-axis [72] wind-turbines, thermo-fluid analysis of ground vehicles and their tires [89], thermo-fluid analysis of disk brakes [90], flow-driven string dynamics in turbomachinery [91], and flow analysis of turbocharger turbines [92,93,94].

The ST-VMS method and ST-IGA with IGA basis functions in space have been successfully utilized in ST computational flow analysis of turbocharger turbines [92,93,94], ram-air parachutes [97], heart valves [84, 86, 87], and tires with road contact and deformation [96]. The turbocharger turbine analysis was based on the integration of the ST-SI method and ST-IGA. The IGA basis functions were used in the spatial discretization of the fluid mechanics equations and also in the temporal representation of the rotor and spinning-mesh motion. That enabled accurate representation of the turbine surfaces and rotor motion and increased accuracy in the flow solution. The meshes used in the turbine analysis presented in [93, 94] was created by the general-purpose NURBS mesh generation method introduced in [93] for complex-geometry flow computations. The ST-SI method is a key player in discretization with this general-purpose mesh generation method; it removes, without loss of accuracy, the matching requirement between the NURBS patches. The ram-air parachute analysis was based on the integration of the ST-IGA, the ST-SI version that weakly enforces the Dirichlet conditions, and the ST-SI version that accounts for the porosity of a thin structure. The ST-IGA with IGA basis functions enabled, with relatively few number of unknowns, accurate representation of the parafoil geometry and increased accuracy in the flow solution. The volume mesh needed to be generated both inside and outside the parafoil, and the mesh generation inside was challenging near the trailing edge because of the narrowing space. Using IGA basis functions addressed that computational challenge and still kept the element density near the trailing edge at a reasonable level. The heart valve analysis was based on the integration of the ST-SI method, ST Topology Change (ST-TC) method [78, 79, 85, 95], and the ST-IGA. The “ST-SI-TC-IGA,” beyond enabling a more accurate representation of the surfaces and increased accuracy in the flow solution, kept the element density in the narrow spaces near the contact areas at a reasonable level. When solid surfaces come into contact, the elements between the surface and the SI collapse. Before the elements collapse, the boundaries could be curved and rather complex, and the narrow spaces might have high-aspect-ratio elements. With NURBS elements, it was possible to deal with such adverse conditions rather effectively. The computational flow analysis of tires with road contact and deformation presented in [96] was also based on the ST-SI-TC-IGA, with essentially the same desirable features as in the heart valve computational flow analysis.

In this article, we integrate the compressible-flow porosity models and ST computational methods with isogeometric discretization. We apply that to flow analysis of a drogue parachute. We use quadratic NURBS basis functions in the computations.

The governing equations are given in Sect. 2, and the porosity models in Appendix A. The compressible-flow ST SUPG and ST-SI methods are given in Appendices B and C. The computations are presented in Sect. 3 and the concluding remarks are given in Sect. 4.

2 Governing equations

Let \(\varOmega _t\subset \mathbb {R}^{n_{\mathrm {sd}}}\) be the spatial domain with boundary \(\varGamma _{t}\) at time \(t \in (0,T)\). The subscript t indicates the time-dependence of the domain. The symbols \(\rho \), \(\mathbf {u}\) and \(p\) will represent the density, velocity and pressure, respectively, and \(\pmb {\varepsilon }(\mathbf {u})= \left( (\pmb {\nabla }\mathbf {u})+(\pmb {\nabla }\mathbf {u})^T\right) /2\) is the strain-rate tensor. The stress tensor is defined as \(\pmb {\sigma }(\mathbf {u}, p) = -p\mathbf {I}+ \mathbf {T}\), where \(\mathbf {I}\) is the identity tensor, and \(\mathbf {T}\) is the Newtonian viscous tensor: \(\mathbf {T}= \lambda (\pmb {\nabla }\cdot \mathbf {u}) \mathbf {I}+ 2 \mu \pmb {\varepsilon }(\mathbf {u})\). Here \(\lambda \) and \(\mu ~(= \rho \nu )\) are the viscosity coefficients, \(\nu \) is the kinematic viscosity, and it is assumed that \(\lambda = - {2 \mu / 3}\).

The Navier–Stokes equations of compressible flows can be written on \(\varOmega _t\) and \(\forall t \in (0,T)\) as

where \(\mathbf {U}= (\rho , \rho u_1, \rho u_2, \rho u_3, \rho e)\) is the vector of conservation variables, \(e\) is the total energy per unit volume, and \(\mathbf {F}_i\) and \(\mathbf {E}_i\) are, respectively, the Euler and viscous flux vectors:

Here \(\delta _{ij}\) are the components of \(\mathbf {I}\), \(q_i\) are the components of the heat flux vector, and \(T_{ij}\) are the components of \(\mathbf {T}\). The equation of state typically corresponds to the ideal gas assumption. The term \(\mathbf {R}\) represents all other components that might enter the equations, including the external forces.

Equation (1) can further be written in the form

where

The essential and natural boundary conditions for Eq. (3) are represented as \(\mathbf {U}\) = \( \mathbf {G}\) on \(\left( \varGamma _t\right) _\mathrm {G}\) and \(n_i \left( \mathbf {K}_{ij} \frac{\partial \mathbf {U}}{\partial x_j}\right) = \mathbf {H}\) on \(\left( \varGamma _t\right) _\mathrm {H}\), where \(\left( \varGamma _t\right) _\mathrm {G}\) and \(\left( \varGamma _t\right) _\mathrm {H}\) are complementary subsets of the boundary \(\varGamma _{t}\), \(n_i\) are the components of the unit normal vector \(\mathbf {n}\), and \(\mathbf {G}\) and \(\mathbf {H}\) are given functions. A function \(\mathbf {U}_{0}(\mathbf {x})\) is specified as the initial condition.

The porosity models we use in conjunction with the governing equations are given in Appendix A. The compressible-flow ST SUPG and ST-SI methods are given in Appendices B and C.

3 Computations

3.1 Parachute description

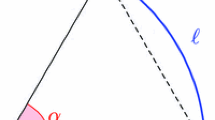

The Orion spacecraft drogue parachute is a variable porosity conical ribbon parachute [6, 7, 9] with a nominal diameter of 23 ft. It has 24 gores, each composed of 52 2-inch horizontal ribbons that are spaced and retained at close intervals by seven parallel, equidistant vertical tapes. The ribbon ends are stitched to the radial lines, which provide the primary longitudinal stiffness. The parachute also includes a vent band, which connects the 24 radial lines terminated at the vent. Figure 1 shows the parachute configuration. The spacing between the ribbons is varied in four levels. The 13 ribbons that are closest to the vent are spaced 0.3 inches apart, and the next three groups of 13 ribbons are spaced 0.4, 0.5 and 0.6 inches apart. Additionally, there are three locations along the gore where ribbons are removed, increasing the overall geometric porosity. These “missing” ribbons allow a localized increase in flow, which helps prevent the boundary layer from reattaching to the canopy, increasing parachute stability.

The ribbons are modeled with membrane elements. The upper, middle and lower ribbons have slightly different material properties. The various lines, tapes and bands are all modeled with cable elements, with material properties that vary by functionality. The material properties were obtained from NASA.

3.2 Flight conditions

The drogue parachute is designed to be used at a wide range of altitudes and Mach numbers. In [10] we had three altitudes, 10,000, 20,000 and 35,000 ft, and three free-stream Mach numbers, 0.3, 0.5 and 0.7. In this article, the free-stream Mach number is 0.3, and we have the same three altitudes as in [10]. We use the same notation as in [10], AM11, AM21, and AM31, where the first digit denotes the altitude, and the second digit the Mach number. Table 1 shows the flight conditions for the three cases.

3.3 Structural mechanics computations

Structural mechanics computations for the drogue parachute are conducted to obtain a deformed shape prior to the fluid mechanics computations.

3.3.1 Problem setup

The structural mechanics mesh, shown in Fig. 2, is a cubic NURBS mesh. It has 91,612 control points and is composed of 6576 membrane elements, 13,249 cable elements, and 1 payload element. The mesh resolution for the ribbons in the radial direction is 1 element.

As the fluid dynamics load on the canopy, we apply a uniform pressure difference equal to the dynamic pressure corresponding to the free-stream density and velocity, \(\varDelta p = \frac{1}{2}\rho _\infty \Vert \mathbf {u}_\infty \Vert ^2\), which can be calculated from Table 1. In each case, we continue the time-dependent structural mechanics computation until a steady-state solution is reached.

3.3.2 Results

Parachute configurations obtained from the structural mechanics computation in the three cases are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The elongation of the three parachutes look quite similar. On the other hand, we see slight differences in the canopy shape. We see more roundness in AM31 than in AM11 because of the lower dynamic pressure.

3.4 One-gore fluid mechanics computations

For the purpose of calculating the porosity coefficients in modeling the geometric porosity in each of the three cases, we compute the flow field for a one-gore (15\(^\circ \)) “slice” of the canopy configuration obtained from the structural mechanics computation.

3.4.1 Problem setup

The fluid mechanics domain for the one-gore slice is a slice of a cylinder with radius of 17.25 ft, height 57.5 ft, and an axial circular hole that has a very small diameter. The distance between the parachute skirt and the inflow boundary is approximately 15 ft. At the inflow, we specify \(\rho \) and \(\mathbf {u}\) in the Euler fluxes, and we drop the terms that we identify as the 3rd, 4th and 5th terms in Eq. (50). At the outflow, we specify stress condition with atmospheric pressure and zero normal heat flux. On the side boundaries, we set the normal velocity weakly to zero and specify zero normal heat flux. On the parachute, when we have porosity, we use the conditions described in Appendix C.4, and when we do not have porosity, we use the conditions enforced by Eq. (53). We resolve the flow through the gaps as well as the wider gaps. In dealing with the fabric porosity, we use Eqs. (19) and (23). In Eq. (19), we set \(\frac{D}{\mu }\) equal to the fabric porosity, and drop the \(\beta \) term.

We use quadratic NURBS meshes. The canopy surface has 3432 control points and 1872 elements. The mesh resolution in the radial direction is 4 elements for the ribbons, 2 or 3 elements for the gaps, and 6 elements for the wider gaps. Figure 5 shows, as an example, the mesh for AM31. The mesh information is given in Table 2. In the case of AM21, we remesh at \(0.33~\mathrm {s}\) to improve the quality of the mesh. Before the remeshing, the mesh has the same connectivity and function space as the mesh for AM31.

The computations are carried out in two stages, first without porosity, and then with porosity. Both stages have 3 nonlinear iterations per time step, and in the GMRES iterations, we use a nodal-block-diagonal preconditioner. The time-step sizes and the number of GMRES iterations per nonlinear iteration are shown in Table 3. We set \(\gamma _\mathrm {ACI}\) = \(-1\) in Eq. (49).

3.4.2 Results

Figures 6 and 7 show the velocity magnitude and density for the three cases. We can see that we are resolving the flow through the gaps as well as the wider gaps.

3.4.3 Geometric-porosity modeling

We calculate the porosity coefficients based on the porosity model represented by Eqs. (19) and (23). The subscript \(\mathrm {G}\) will refer to the geometric porosity, and the area is divided into four patches, as shown in Fig. 8. Figures 9 and 10 show the patch-averaged values of \(|\dot{m}|\) through the gaps and \(\mathcal {M}^2\). In the periods with fabric porosity, these values decrease with increasing altitude for all patches, because the density, velocity and dynamic pressure all decrease with increasing altitude (see Table 1). Figure 11 shows the correlation between the time-averaged values of \(|\dot{m}|\) and \(\mathcal {M}^2\) displayed in Figs. 9 and 10, with the intervals used in the time-averaging shown in those two figures. The correlation is established by least-squares curve fitting based on Eq. (19), which yields \(\frac{\mu }{D}\) and \(\beta \) that represent the geometric porosity of the gaps, and we call those \(\left( \frac{\mu }{D} \right) _\mathrm {G}\) and \(\beta _\mathrm {G}\). Table 4 shows, for each patch, the \(\left( \frac{\mu }{D} \right) _\mathrm {G}\) and \(\beta _\mathrm {G}\) values, and the coefficient of determination in the curve fitting.

3.5 Full-canopy fluid mechanics computation

3.5.1 Modeled porosity

In the full-canopy fluid mechanics computations with the modeled porosity, for each patch, the relationship between \(\mathcal {M}^2\) and \(|\dot{m}|\) is given as

where the subscript \(\mathrm {F}\) refers to the fabric porosity, \(A_\mathrm {F}\) is the total fabric area for the patch, \(A_1\) is the fluid surface area for the patch, taken as \(A_1\)\(\approx \)\(A_\mathrm {F} + A_\mathrm {G}\) here, \(\left( \frac{D}{\mu }\right) _\mathrm {F}\) is set equal to the fabric porosity, taken as 40 CFM here, and \(\beta _\mathrm {F}\) = 0 here. Figure 12 shows that relationship for all the patches. Table 5 shows, for all the cases and patches, the values of \(\frac{\mu }{D}\) and \(\beta \) used in Eq. (5).

3.5.2 Computation

We do the full-canopy fluid mechanics computation for AM31. The domain is a cylinder with diameter 96.5 ft and height 96.5 ft. The distance between the parachute skirt and the inflow boundary is approximately 33 ft. The boundary conditions are the same as those described in 3.4.1 for the one-gore fluid mechanics computations.

We use a quadratic NURBS mesh. The number of control points and elements for the volume mesh are 270,296 and 190,464. The canopy surface has 6336 control points and 5040 elements. The mesh resolution in the radial direction for the wider gaps is 3 elements.

Figures 13 and 14 show the surface and volume meshes. The computations are carried out in three stages, first without porosity, and the second and the third with porosity. The time-step size for first and second stages is \(5.0{\times }10^{-5}~\mathrm {s}\), and for the third stage \(5.0{\times }10^{-4}~\mathrm {s}\). In all three stages, we have 3 nonlinear iterations per time step and 60 GMRES iterations per nonlinear iteration. In the GMRES iterations, we use a nodal-block-diagonal preconditioner. We set \(\gamma _\mathrm {ACI}\) = \(-1\) in Eq. (49).

Figures 15 and 16 show the velocity and density for AM31 after a settled solution is reached.

4 Concluding remarks

Geometric porosity, a design feature in spacecraft parachutes, is created by the hundreds of gaps and slits that the flow goes through. Accurate geometric-porosity modeling is essential. That is because FSI analysis with resolved geometric porosity would require resolving the flow that goes through the hundreds of gaps and slits as they change their shapes during the computation, which would be exceedingly time-consuming. The geometric-porosity model introduced earlier in conjunction with the ST computational methods, the HMGP, enabled successful computational analysis and design studies of the Orion spacecraft main parachutes, which operate in the incompressible-flow regime. Recently, porosity models and ST computational methods were introduced, in the context of finite element discretization, for compressible-flow aerodynamics of parachutes with geometric porosity. The key new component of the ST computational framework was the compressible-flow ST-SI method, introduced in conjunction with the compressible-flow ST SUPG method. Here, we integrated these porosity models and ST computational methods with isogeometric discretization and applied that to flow analysis of the Orion spacecraft drogue parachute, which operates in the compressible-flow regime. We used quadratic NURBS basis functions in the computations. That gives us a parachute shape that is smoother than what we get from a typical finite element discretization. In the flow analysis, the combination of the ST framework, NURBS basis functions, and the SUPG stabilization assures superior computational accuracy. The ST-SI plays a key role not only by enabling the porosity modeling with its version where the SI is between a thin porous structure and the fluid on its two sides, but also by removing, without loss of accuracy, the matching requirement between the NURBS patches. The porosity coefficients used in modeling the geometric porosity are determined in high-resolution computation of the flow field for a slice of the parachute canopy with the Mach number given and over a range of altitudes. In these high-resolution computations, the flow going though each gap is resolved. After performing those computations for the drogue parachute, using the porosity coefficients obtained, we performed a full-canopy flow computation. The computations show the effectiveness of the porosity models, ST computational methods, and the integration with isogeometric discretization.

References

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2012) Computational methods for parachute fluid-structure interactions. Arch Comput Methods Eng 19:125–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-012-9070-4

Bazilevs Y, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2013) Computational fluid–structure interaction: methods and applications. Wiley, Hoboken. ISBN 978-0470978771

Takizawa K, Fritze M, Montes D, Spielman T, Tezduyar TE (2012) Fluid-structure interaction modeling of ringsail parachutes with disreefing and modified geometric porosity. Comput Mech 50:835–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-012-0761-3

Takizawa K, Montes D, Fritze M, McIntyre S, Boben J, Tezduyar TE (2013) Methods for FSI modeling of spacecraft parachute dynamics and cover separation. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 23:307–338. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202513400058

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Boben J, Kostov N, Boswell C, Buscher A (2013) Fluid-structure interaction modeling of clusters of spacecraft parachutes with modified geometric porosity. Comput Mech 52:1351–1364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-013-0880-5

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Boswell C, Kolesar R, Montel K (2014) FSI modeling of the reefed stages and disreefing of the Orion spacecraft parachutes. Comput Mech 54:1203–1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1052-y

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Kolesar R, Boswell C, Kanai T, Montel K (2014) Multiscale methods for gore curvature calculations from FSI modeling of spacecraft parachutes. Comput Mech 54:1461–1476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1069-2

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Boswell C, Tsutsui Y, Montel K (2015) Special methods for aerodynamic-moment calculations from parachute FSI modeling. Comput Mech 55:1059–1069. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1074-5

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Kolesar R (2015) FSI modeling of the orion spacecraft drogue parachutes. Comput Mech 55:1167–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1108-z

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Kanai T (2017) Porosity models and computational methods for compressible-flow aerodynamics of parachutes with geometric porosity. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 27:771–806. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202517500166

Tezduyar TE (1992) Stabilized finite element formulations for incompressible flow computations. Adv Appl Mech 28:1–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2156(08)70153-4

Tezduyar TE (2003) Computation of moving boundaries and interfaces and stabilization parameters. Int J Numer Meth Fluids 43:555–575. https://doi.org/10.1002/fld.505

Tezduyar TE, Sathe S (2007) Modeling of fluid–structure interactions with the space-time finite elements: solution techniques. Int J Numer Method Fluids 54:855–900. https://doi.org/10.1002/fld.1430

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2011) Multiscale space-time fluid–structure interaction techniques. Comput Mech 48:247–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-011-0571-z

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2012) Space-time fluid-structure interaction methods. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 22(supp02):1230001. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202512300013

Tezduyar TE, Behr M, Liou J (1992) A new strategy for finite element computations involving moving boundaries and interfaces—the deforming-spatial-domain/space-time procedure: I. The concept and the preliminary numerical tests. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 94(3):339–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7825(92)90059-S

Tezduyar TE, Behr M, Mittal S, Liou J (1992) A new strategy for finite element computations involving moving boundaries and interfaces—the deforming-spatial-domain/space-time procedure: II. Computation of free-surface flows, two-liquid flows, and flows with drifting cylinders. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 94(3):353–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7825(92)90060-W

Brooks AN, Hughes TJR (1982) Streamline upwind/Petrov–Galerkin formulations for convection dominated flows with particular emphasis on the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 32:199–259

Hughes TJR (1995) Multiscale phenomena: green’s functions, the Dirichlet-to-Neumann formulation, subgrid scale models, bubbles, and the origins of stabilized methods. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 127:387–401

Hughes TJR, Oberai AA, Mazzei L (2001) Large eddy simulation of turbulent channel flows by the variational multiscale method. Phys Fluids 13:1784–1799

Bazilevs Y, Calo VM, Cottrell JA, Hughes TJR, Reali A, Scovazzi G (2007) Variational multiscale residual-based turbulence modeling for large eddy simulation of incompressible flows. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 197:173–201

Bazilevs Y, Akkerman I (2010) Large eddy simulation of turbulent Taylor–Couette flow using isogeometric analysis and the residual-based variational multiscale method. J Comput Phys 229:3402–3414

Bazilevs Y, Calo VM, Hughes TJR, Zhang Y (2008) Isogeometric fluid–structure interaction: theory, algorithms, and computations. Comput Mech 43:3–37

Takizawa K, Bazilevs Y, Tezduyar TE (2012) Space-time and ALE-VMS techniques for patient-specific cardiovascular fluid–structure interaction modeling. Arch Comput Methods Eng 19:171–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-012-9071-3

Bazilevs Y, Hsu M-C, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2012) ALE-VMS and ST-VMS methods for computer modeling of wind-turbine rotor aerodynamics and fluid–structure interaction. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 22(supp02):1230002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202512300025

Bazilevs Y, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2013) Challenges and directions in computational fluid–structure interaction. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 23:215–221. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202513400010

Bazilevs Y, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2015) New directions and challenging computations in fluid dynamics modeling with stabilized and multiscale methods. Mathematical Models Methods Appl Sci 25:2217–2226. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202515020029

Hughes TJR, Liu WK, Zimmermann TK (1981) Lagrangian–Eulerian finite element formulation for incompressible viscous flows. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 29:329–349

Bazilevs Y, Hughes TJR (2007) Weak imposition of Dirichlet boundary conditions in fluid mechanics. Comput Fluids 36:12–26

Bazilevs Y, Michler C, Calo VM, Hughes TJR (2010) Isogeometric variational multiscale modeling of wall-bounded turbulent flows with weakly enforced boundary conditions on unstretched meshes. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 199:780–790

Hsu M-C, Akkerman I, Bazilevs Y (2012) Wind turbine aerodynamics using ALE-VMS: validation and role of weakly enforced boundary conditions. Comput Mech 50:499–511

Bazilevs Y, Hughes TJR (2008) NURBS-based isogeometric analysis for the computation of flows about rotating components. Comput Mech 43:143–150

Hsu M-C, Bazilevs Y (2012) Fluid–structure interaction modeling of wind turbines: simulating the full machine. Comput Mech 50:821–833

Moghadam ME, Bazilevs Y, Hsia T-Y, Vignon-Clementel IE, Marsden AL, M. of Congenital Hearts Alliance (MOCHA) (2011) A comparison of outlet boundary treatments for prevention of backflow divergence with relevance to blood flow simulations. Comput Mech 48:277–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-011-0599-0

Bazilevs Y, Hsu M-C, Akkerman I, Wright S, Takizawa K, Henicke B, Spielman T, Tezduyar TE (2011) 3D simulation of wind turbine rotors at full scale. Part I: geometry modeling and aerodynamics. Int J Numer Meth Fluids 65:207–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/fld.2400

Bazilevs Y, Hsu M-C, Kiendl J, Wüchner R, Bletzinger K-U (2011) 3D simulation of wind turbine rotors at full scale. Part II: Fluid–structure interaction modeling with composite blades. Int J Numer Meth Fluids 65:236–253

Hsu M-C, Akkerman I, Bazilevs Y (2011) High-performance computing of wind turbine aerodynamics using isogeometric analysis. Comput Fluids 49:93–100

Bazilevs Y, Hsu M-C, Scott MA (2012) Isogeometric fluid-structure interaction analysis with emphasis on non-matching discretizations, and with application to wind turbines. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 249–252:28–41

Hsu M-C, Akkerman I, Bazilevs Y (2014) Finite element simulation of wind turbine aerodynamics: validation study using NREL Phase VI experiment. Wind Energy 17:461–481

Korobenko A, Hsu M-C, Akkerman I, Tippmann J, Bazilevs Y (2013) Structural mechanics modeling and FSI simulation of wind turbines. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 23:249–272

Bazilevs Y, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Hsu M-C, Kostov N, McIntyre S (2014) Aerodynamic and FSI analysis of wind turbines with the ALE-VMS and ST-VMS methods. Arch Comput Methods Eng 21:359–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-014-9119-7

Bazilevs Y, Korobenko A, Deng X, Yan J (2015) Novel structural modeling and mesh moving techniques for advanced FSI simulation of wind turbines. Int J Numer Meth Eng 102:766–783. https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.4738

Korobenko A, Hsu M-C, Akkerman I, Bazilevs Y (2013) Aerodynamic simulation of vertical-axis wind turbines. J Appl Mech 81:021011. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4024415

Bazilevs Y, Korobenko A, Deng X, Yan J, Kinzel M, Dabiri JO (2014) FSI modeling of vertical-axis wind turbines. J Appl Mech 81:081006. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4027466

Yan J, Korobenko A, Deng X, Bazilevs Y (2016) Computational free-surface fluid–structure interaction with application to floating offshore wind turbines. Comput Fluids 141:155–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2016.03.008

Bazilevs Y, Korobenko A, Yan J, Pal A, Gohari SMI, Sarkar S (2015) ALE-VMS formulation for stratified turbulent incompressible flows with applications. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 25:2349–2375. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202515400114

Bazilevs Y, Korobenko A, Deng X, Yan J (2016) FSI modeling for fatigue-damage prediction in full-scale wind-turbine blades. J Appl Mech 83(6):061010

Bazilevs Y, Calo VM, Zhang Y, Hughes TJR (2006) Isogeometric fluid–structure interaction analysis with applications to arterial blood flow. Comput Mech 38:310–322

Bazilevs Y, Gohean JR, Hughes TJR, Moser RD, Zhang Y (2009) Patient-specific isogeometric fluid–structure interaction analysis of thoracic aortic blood flow due to implantation of the Jarvik 2000 left ventricular assist device. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 198:3534–3550

Bazilevs Y, Hsu M-C, Benson D, Sankaran S, Marsden A (2009) Computational fluid–structure interaction: methods and application to a total cavopulmonary connection. Comput Mech 45:77–89

Bazilevs Y, Hsu M-C, Zhang Y, Wang W, Liang X, Kvamsdal T, Brekken R, Isaksen J (2010) A fully-coupled fluid–structure interaction simulation of cerebral aneurysms. Comput Mech 46:3–16

Bazilevs Y, Hsu M-C, Zhang Y, Wang W, Kvamsdal T, Hentschel S, Isaksen J (2010) Computational fluid–structure interaction: methods and application to cerebral aneurysms. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 9:481–498

Hsu M-C, Bazilevs Y (2011) Blood vessel tissue prestress modeling for vascular fluid–structure interaction simulations. Finite Elem Anal Des 47:593–599

Long CC, Marsden AL, Bazilevs Y (2013) Fluid–structure interaction simulation of pulsatile ventricular assist devices. Comput Mech 52:971–981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-013-0858-3

Long CC, Esmaily-Moghadam M, Marsden AL, Bazilevs Y (2014) Computation of residence time in the simulation of pulsatile ventricular assist devices. Comput Mech 54:911–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-013-0931-y

Long CC, Marsden AL, Bazilevs Y (2014) Shape optimization of pulsatile ventricular assist devices using FSI to minimize thrombotic risk. Comput Mech 54:921–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-013-0967-z

Hsu M-C, Kamensky D, Bazilevs Y, Sacks MS, Hughes TJR (2014) Fluid-structure interaction analysis of bioprosthetic heart valves: significance of arterial wall deformation. Comput Mech 54:1055–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1059-4

Hsu M-C, Kamensky D, Xu F, Kiendl J, Wang C, Wu MCH, Mineroff J, Reali A, Bazilevs Y, Sacks MS (2015) Dynamic and fluid-structure interaction simulations of bioprosthetic heart valves using parametric design with T-splines and Fung-type material models. Comput Mech 55:1211–1225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-015-1166-x

Kamensky D, Hsu M-C, Schillinger D, Evans JA, Aggarwal A, Bazilevs Y, Sacks MS, Hughes TJR (2015) An immersogeometric variational framework for fluid–structure interaction: application to bioprosthetic heart valves. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 284:1005–1053

Akkerman I, Bazilevs Y, Benson DJ, Farthing MW, Kees CE (2012) Free-surface flow and fluid-object interaction modeling with emphasis on ship hydrodynamics. J Appl Mech 79:010905

Akkerman I, Dunaway J, Kvandal J, Spinks J, Bazilevs Y (2012) Toward free-surface modeling of planing vessels: simulation of the Fridsma hull using ALE-VMS. Comput Mech 50:719–727

Wang C, Wu MCH, Xu F, Hsu M-C, Bazilevs Y (2017) Modeling of a hydraulic arresting gear using fluid–structure interaction and isogeometric analysis. Comput Fluids 142:3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2015.12.004

Wu MCH, Kamensky D, Wang C, Herrema AJ, Xu F, Pigazzini MS, Verma A, Marsden AL, Bazilevs Y, Hsu M-C (2017) Optimizing fluid-structure interaction systems with immersogeometric analysis and surrogate modeling: Application to a hydraulic arresting gear. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2016.09.032

Yan J, Deng X, Korobenko A, Bazilevs Y (2017) Free-surface flow modeling and simulation of horizontal-axis tidal-stream turbines. Comput Fluids 158:157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2016.06.016

Augier B, Yan J, Korobenko A, Czarnowski J, Ketterman G, Bazilevs Y (2015) Experimental and numerical FSI study of compliant hydrofoils. Comput Mech 55:1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1090-5

Yan J, Augier B, Korobenko A, Czarnowski J, Ketterman G, Bazilevs Y (2016) FSI modeling of a propulsion system based on compliant hydrofoils in a tandem configuration. Comput Fluids 141:201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2015.07.013

Takizawa K, Henicke B, Tezduyar TE, Hsu M-C, Bazilevs Y (2011) Stabilized space-time computation of wind-turbine rotor aerodynamics. Comput Mech 48:333–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-011-0589-2

Takizawa K, Henicke B, Montes D, Tezduyar TE, Hsu M-C, Bazilevs Y (2011) Numerical-performance studies for the stabilized space-time computation of wind-turbine rotor aerodynamics. Comput Mech 48:647–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-011-0614-5

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, McIntyre S, Kostov N, Kolesar R, Habluetzel C (2014) Space-time VMS computation of wind-turbine rotor and tower aerodynamics. Comput Mech 53:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-013-0888-x

Takizawa K, Bazilevs Y, Tezduyar TE, Hsu M-C, Øiseth O, Mathisen KM, Kostov N, McIntyre S (2014) Engineering analysis and design with ALE-VMS and space-time methods. Arch Comput Methods Eng 21:481–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-014-9113-0

Takizawa K (2014) Computational engineering analysis with the new-generation space-time methods. Comput Mech 54:193–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-0999-z

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Mochizuki H, Hattori H, Mei S, Pan L, Montel K (2015) Space-time VMS method for flow computations with slip interfaces (ST-SI). Math Models Methods Appl Sci 25:2377–2406. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202515400126

Takizawa K, Henicke B, Puntel A, Spielman T, Tezduyar TE (2012) Space-time computational techniques for the aerodynamics of flapping wings. J Appl Mech 79:010903. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4005073

Takizawa K, Henicke B, Puntel A, Kostov N, Tezduyar TE (2012) Space-time techniques for computational aerodynamics modeling of flapping wings of an actual locust. Comput Mech 50:743–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-012-0759-x

Takizawa K, Henicke B, Puntel A, Kostov N, Tezduyar TE (2013) Computer modeling techniques for flapping-wing aerodynamics of a locust. Comput Fluids 85:125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2012.11.008

Takizawa K, Kostov N, Puntel A, Henicke B, Tezduyar TE (2012) Space-time computational analysis of bio-inspired flapping-wing aerodynamics of a micro aerial vehicle. Comput Mech 50:761–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-012-0758-y

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Kostov N (2014) Sequentially-coupled space-time FSI analysis of bio-inspired flapping-wing aerodynamics of an MAV. Comput Mech 54:213–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-0980-x

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Buscher A, Asada S (2014) Space-time interface-tracking with topology change (ST-TC). Comput Mech 54:955–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-013-0935-7

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Buscher A (2015) Space-time computational analysis of MAV flapping-wing aerodynamics with wing clapping. Comput Mech 55:1131–1141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1095-0

Takizawa K, Bazilevs Y, Tezduyar TE, Long CC, Marsden AL, Schjodt K (2014) ST and ALE-VMS methods for patient-specific cardiovascular fluid mechanics modeling. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 24:2437–2486. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202514500250

Takizawa K, Schjodt K, Puntel A, Kostov N, Tezduyar TE (2012) Patient-specific computer modeling of blood flow in cerebral arteries with aneurysm and stent. Comput Mech 50:675–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-012-0760-4

Takizawa K, Schjodt K, Puntel A, Kostov N, Tezduyar TE (2013) Patient-specific computational analysis of the influence of a stent on the unsteady flow in cerebral aneurysms. Comput Mech 51:1061–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-012-0790-y

Suito H, Takizawa K, Huynh VQH, Sze D, Ueda T (2014) FSI analysis of the blood flow and geometrical characteristics in the thoracic aorta. Comput Mech 54:1035–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1017-1

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Uchikawa H, Terahara T, Sasaki T, Shiozaki K, Yoshida A, Komiya K, Inoue G (2018) “Aorta flow analysis and heart valve flow and structure analysis”, to appear in a special volume to be published by Springer

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Buscher A, Asada S (2014) Space-time fluid mechanics computation of heart valve models. Comput Mech 54:973–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1046-9

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Terahara T, Sasaki T (2018) Heart valve flow computation with the Space–Time Slip Interface Topology Change (ST-SI-TC) method and Isogeometric Analysis (IGA). In: Wriggers P, Lenarz T (eds) Biomedical technology: modeling, experiments and simulation, lecture notes in applied and computational mechanics, 77–99, Springer, ISBN 978-3-319-59547-4

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Terahara T, Sasaki T (2017) Heart valve flow computation with the integrated Space-time VMS, slip interface, topology change and isogeometric discretization methods. Comput Fluids 158:176–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2016.11.012

Takizawa K, Montes D, McIntyre S, Tezduyar TE (2013) Space-time VMS methods for modeling of incompressible flows at high Reynolds numbers. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 23:223–248. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0218202513400022

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Kuraishi T (2015) Multiscale ST methods for thermo-fluid analysis of a ground vehicle and its tires. Math Models Methods Appl Sci 25:2227–2255. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218202515400072

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Kuraishi T, Tabata S, Takagi H (2016) Computational thermo-fluid analysis of a disk brake. Comput Mech 57:965–977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-016-1272-4

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Hattori H (2017) Computational analysis of flow-driven string dynamics in turbomachinery. Comput Fluids 142:109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2016.02.019

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Otoguro Y, Terahara T, Kuraishi T, Hattori H (2017) Turbocharger flow computations with the space-time isogeometric analysis (ST-IGA). Comput Fluids 142:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2016.02.021

Otoguro Y, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2017) Space-time VMS computational flow analysis with isogeometric discretization and a general-purpose NURBS mesh generation method. Comput Fluids 158:189–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2017.04.017

Otoguro Y, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2018) A general-purpose NURBS mesh generation method for complex geometries, to appear in a special volume to be published by Springer

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Asada S, Kuraishi T (2016) Space-time method for flow computations with slip interfaces and topology changes (ST-SI-TC). Comput Fluids 141:124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2016.05.006

Kuraishi T, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2018) Space–time computational analysis of tire aerodynamics with actual geometry, road contact and tire deformation, to appear in a special volume to be published by Springer

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Terahara T (2016) Ram-air parachute structural and fluid mechanics computations with the space-time isogeometric analysis (ST-IGA). Comput Fluids 141:191–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2016.05.027

Tezduyar TE, Sathe S, Pausewang J, Schwaab M, Christopher J, Crabtree J (2008) Interface projection techniques for fluid-structure interaction modeling with moving-mesh methods. Comput Mech 43:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-008-0261-7

Tezduyar T, Aliabadi S, Behr M, Johnson A, Kalro V, Litke M (1996) Flow simulation and high performance computing. Comput Mech 18:397–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00350249

Tezduyar TE, Hughes TJR (1982) Development of time-accurate finite element techniques for first-order hyperbolic systems with particular emphasis on the compressible Euler equations. NASA technical report NASA-CR-204772, NASA, http://www.researchgate.net/publication/24313718/

Tezduyar TE, Hughes TJR (1983) Finite element formulations for convection dominated flows with particular emphasis on the compressible Euler equations. In: Proceedings of AIAA 21st aerospace sciences meeting, AIAA Paper 83-0125, Reno, Nevada. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.1983-125

Hughes TJR, Tezduyar TE (1984) Finite element methods for first-order hyperbolic systems with particular emphasis on the compressible Euler equations. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 45:217–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7825(84)90157-9

Le Beau GJ, Tezduyar TE (1991) Finite element computation of compressible flows with the SUPG formulation. In: Advances in finite element analysis in fluid dynamics, FED-Vol.123, ASME, New York, pp 21–27

Le Beau GJ, Ray SE, Aliabadi SK, Tezduyar TE (1993) SUPG finite element computation of compressible flows with the entropy and conservation variables formulations. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 104:397–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7825(93)90033-T

Tezduyar TE (2004) Determination of the stabilization and shock-capturing parameters in SUPG formulation of compressible flows. In: Proceedings of the European congress on computational methods in applied sciences and engineering, ECCOMAS 2004 (CD-ROM), Jyvaskyla, Finland

Tezduyar TE (2004) Finite element methods for fluid dynamics with moving boundaries and interfaces. In: Stein E, Borst RD, Hughes TJR (eds) Encyclopedia of computational mechanics, Volume 3: Fluids, Chapter 17, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-470-84699-5

Tezduyar TE (2007) Finite elements in fluids: stabilized formulations and moving boundaries and interfaces. Comput Fluids 36:191–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2005.02.011

Tezduyar TE, Senga M (2006) Stabilization and shock-capturing parameters in SUPG formulation of compressible flows. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 195:1621–1632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2005.05.032

Tezduyar TE, Senga M (2007) SUPG finite element computation of inviscid supersonic flows with YZ\(\beta \) shock-capturing. Comput Fluids 36:147–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2005.07.009

Tezduyar TE, Senga M, Vicker D (2006) Computation of inviscid supersonic flows around cylinders and spheres with the SUPG formulation and YZ\(\beta \) shock-capturing. Comput Mech 38:469–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-005-0025-6

Hughes TJR, Cottrell JA, Bazilevs Y (2005) Isogeometric analysis: CAD, finite elements, NURBS, exact geometry, and mesh refinement. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 194:4135–4195

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE (2014) Space-time computation techniques with continuous representation in time (ST-C). Comput Mech 53:91–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-013-0895-y

Tezduyar TE, Aliabadi SK, Behr M, Mittal S (1994) Massively parallel finite element simulation of compressible and incompressible flows. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 119:157–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7825(94)00082-4

Tezduyar TE (2001) Finite element methods for flow problems with moving boundaries and interfaces. Arch Comput Methods Eng 8:83–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02897870

Rispoli F, Delibra G, Venturini P, Corsini A, Saavedra R, Tezduyar TE (2015) Particle tracking and particle–shock interaction in compressible-flow computations with the V-SGS stabilization and YZ\(\beta \) shock-capturing. Comput Mech 55:1201–1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-015-1160-3

Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Otoguro Y (2018) Stabilization and discontinuity-capturing parameters for space–time flow computations with finite element and isogeometric discretizations. Comput Mech published online, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-018-1557-x

Arnold DN (1982) An interior penalty finite element method with discontinuous elements. SIAM J Numer Anal 19:742–760

Riviere B, Wheeler MF, Girault V (2001) A priori error estimates for finite element methods based on discontinuous approximation spaces for elliptic problems. SIAM J Numer Anal 39:902–931

Hartmann R, Houston P (2008) An optimal order interior penalty discontinuous Galerkin discretization of the compressible Navier–Stokes equations. J Comput Phys 227:9670–9685

Otoguro Y, Takizawa K, Tezduyar TE, Nagaoka K, Mei S (2018) Turbocharger turbine and exhaust manifold flow computation with the Space–Time Variational Multiscale Method and Isogeometric Analysis. Comput Fluids. published online, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2018.05.019

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) 24760144 from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS); Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research 16K13779 from JSPS; Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) 26220002 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT); Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI), Cross-Ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP), “Innovative Combustion Technology” (Funding agency: JST); and Rice–Waseda research agreement. This work was also supported (first author) in part by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow 16J10373. The mathematical model and computational method parts of the work were also supported (third author) in part by ARO Grant W911NF-17-1-0046 and Top Global University Project of Waseda University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Porosity models

Consider a porous media as shown in Fig. 17. The flow is only in the normal direction, and across the media the mass flow rate is invariant and the pressure is continuous. The temperature-related condition will be described later. We assume that, compared to the fluxes, the term

is negligible. Then, the mass flow rate across the media,

is constant. Here, \(u_\mathrm {R}\) is the velocity relative to the porous media, which is only in the normal direction.

Schematic representation of a porous media. The coordinates \(x_B\) and \(x_A \) represent the “B” (“below”) and “A” (“above”) sides of the media. The flow direction from the B side to the A side is taken as the positive flow direction. The flow is only in the normal direction, and across the media the mass flow rate is invariant and the pressure is continuous. The temperature-related condition will be described later

We assume that the pressure gradient can be expressed as

where S and L are model parameters. This is know as the Darcy–Forchheimer model. We assume a polytropic process in the media:

where n is the exponent constant, and C is a constant. This is general enough to cover most processes.

1.1 Relationship between the fluid inside the media and the surrounding fluid

Multiplying Eq. (8) with the density, we obtain

and using Eq. (9), we can integrate in the normal direction:

With the transformed model parameters defined as

the integration yields

Substituting for C from Eq. (9), we obtain

1.2 Mass flux

We define \(\mathcal {M}^2\) as

and because

the definition translates to

With that, we rewrite Eq. (15) as

and this is the equation we solve for \(\left| \dot{m}\right| \). We obtain

for \(\beta \ne 0\), and the form

would be applicable also when \(\beta = 0\). From that, we can get

Remark 1

Setting \(n = \gamma \) gives us \(\mathcal {M}^2\) for adiabatic process:

Remark 2

Setting \(n = \infty \) gives us \(\mathcal {M}^2\) for incompressible-flow process:

1.3 Momentum flux

The force acting on the fluid per unit area due to the media, \(\mathbf {h}_\mathrm {M}\), is expressed in terms of the momentum-conservation fluxes on the two sides:

1.4 Energy flux

Neglecting the energy exchange due to viscous forces, the heat leaving from the fluid to the media, \(q_\mathrm {M}\), is expressed in terms of the energy-conservation fluxes on the two sides:

where the unit normal vector \(\mathbf {n}\) is pointing from the B side to the A side. Heat flux condition between a thin porous structure and the surrounding fluid specifies \(q_\mathrm {M}\) to a given value. As a special case of that, the adiabatic condition between a thin porous structure and the surrounding fluid specifies \(q_\mathrm {M}\) to zero.

Compressible-flow ST SUPG method

The compressible-flow ST SUPG method is essentially the same as the compressible-flow DSD/SST method, but without necessarily implying a mesh motion. The compressible-flow DSD/SST method is a straightforward mixture of the DSD/SST concept and the compressible-flow SUPG method. The compressible-flow SUPG method [101,102,103,104] was introduced in 1982 and evolved over the years (see Sect. 1). The DSD/SST method [2, 11,12,13,14,15], introduced in 1990, also evolved over the years (see Sect. 1 and [2]).

In the DSD/SST method, the finite element formulation is written over a sequence of N ST slabs \(Q_n\), where \(Q_n\) is the slice of the ST domain between the time levels \(t_n\) and \(t_{n+1}\). The lateral boundary \(P_n\) will have complementary subsets where essential and natural boundary conditions are enforced, just like how it is with \(\varGamma _{t}\). At each time step, the integrations are performed over \(Q_n\). The functions are continuous within an ST slab, but discontinuous from one ST slab to another, and the superscripts “−” and “\(+\)” will indicate the values of the functions just below and just above the time level. The trial solution and test function spaces are defined over \(Q_n\) by using ST polynomials that are typically first-order, but sometimes higher-order. Each \(Q_n\) is decomposed into elements \(Q_n^e\), where \(e=1,2,\ldots ,(n_{\mathrm {el}})_n\). The subscript n used with \(n_{\mathrm {el}}\) is for the general case where the number of ST elements may change from one ST slab to another.

We assume that we have constructed some suitably-defined finite-dimensional trial solution and test function spaces \((\mathcal {S}_U^h)_n\) and \((\mathcal {V}_U^h)_n\). The DSD/SST formulation [106,107,108,109,110, 113,114,115] of Eq. (3) can be written as follows: given \((\mathbf {U}^h)_{n}^-\), find \(\mathbf {U}^h \in (\mathcal {S}_U^h)_n\), such that \(\forall \mathbf {W}^h \in (\mathcal {V}_U^h)_n\):

where

\(\pmb {\tau }_{\mathrm {SUPG}}\) is the SUPG stabilization matrix, and \(\nu _\mathrm {SHOC}\) is the shock-capturing parameter. The stabilization is residual-based because the residual of the compressible-flow equations, \(\mathbf {R}_{\mathrm {A}}(\mathbf {U}^h)\), appears as a factor in the stabilization term. We start with \((\mathbf {U}^h)_{0}^-\) = \(\mathbf {U}_{0}(\mathbf {x})\) and apply the formulation sequentially to all ST slabs \(Q_0, Q_1, Q_2, \ldots , Q_{N-1}\). The stabilization matrix is given from [106, 108,109,110] and [116] as

where

and

The symbols \(\theta \) and \(\nu ^e\) represent the temperature and the thermal diffusivity. See Appendix D for the definition of \(\mathbf {G}^\mathrm {ST}\) and \(\mathbf {G}\). The parameter \(\nu _\mathrm {SHOC}\) is defined as

where

\(\mathbf {Y}\) is a diagonal scaling matrix constructed from the reference values of the components of \(\mathbf {U}\), and \(\mathbf {Z} = \mathbf {A}_i^h \frac{\partial \mathbf {U}^h}{\partial x_i}\) or \(\mathbf {Z} = \mathbf {R}_{\mathrm {A}}(\mathbf {U}^h)\). In the computations reported here, we use \(\beta = 1\) and \(\mathbf {Z} = \mathbf {A}_i^h \frac{\partial \mathbf {U}^h}{\partial x_i}.\)

Compressible-flow ST-SI method

1.1 ST-SI base version

First we define a new function and introduce a notation based on that:

where \(\mathbf {v}\) is the mesh velocity and \(v_i\) is its ith component. In the ST-SI method associated with the formulation given by Eq. (27), there will be added boundary terms corresponding to the SI. We will use the labels “Side A” and “Side B” to represents the two sides of the SI. The boundary terms for the two sides will first be added separately, using test functions \({\mathbf {W}}_\mathrm {A}^h\) and \({\mathbf {W}}_\mathrm {B}^h\). Then, putting together the terms added for each side, the complete set of terms added will be obtained. We give the boundary terms for only Side B:

where

Here, \(\left( P_n\right) _\mathrm {SI}\) is the SI in the ST domain, \(c\) is the acoustic speed, and \(\mathbf {C}^h\) is a tensor that will be defined later. Side A counterpart of Eq. (43) can be written by just interchanging subscripts A and B. For the definition of \(\mathbf {G}\), see Appendix D.

Remark 3

The first and second integrations set the Euler flux at the boundary to the Lax–Friedrichs flux.

Remark 4

The third integration contains the average viscous terms.

Remark 5

The fourth integration, with \(\gamma _\mathrm {ACI}=1\), is the adjoint consistency term introduced in the symmetric-interior-penalty discontinuous Galerkin method [117]. The other choice is \(\gamma _\mathrm {ACI}=-1\), resulting in a method that is adjoint inconsistent, which is known as the nonsymmetric-interior-penalty discontinuous Galerkin method [118].

Remark 6

The fifth integration is a penalty-like term. Several forms of the tensor \(\mathbf {C}^h\) have been proposed and we use the one from [119]:

where C is a nondimensional positive constant, which is 1.0 in the computations reported in this article.

Remark 7

The element length given in Eqs. (45)–(47) was introduced in [120], partly based on [116], in the context of incompressible flow.

Putting together the boundary terms added for each side, the complete set of terms added becomes

1.2 ST-SI version where the SI is a fluid–solid interface with weakly-imposed flow velocity and temperature conditions

The boundary terms added for Side B are given as

where

and \(\mathbf {g}^h\) and \(g_\theta ^h\) are given functions.

1.3 ST-SI version where the SI is a fluid–solid interface with weakly-imposed flow velocity and adiabatic conditions

The boundary terms added for Side B are given as

where

Note that \(\mathbf {U}_{,j} = \frac{\partial \mathbf {U}}{\partial x_j}\).

1.4 ST-SI version where the SI is the interface between a thin porous structure and the surrounding fluid with weakly-imposed flow velocity and adiabatic conditions

In general, the adiabatic condition (\(q_\mathrm {M} = 0\)) between the thin structure and the surrounding fluid implies

As a special case of that, we might have

1.4.1 Special case

From Eq. (22) with Eq. (23), we obtain the mass flux as a function of the two conservation variables:

The boundary terms added for Side B are given as

Here the normal components of the Euler flux vectors are taken as

where

The normal components of the viscous flux vectors, not including the heat conduction flux, are taken as

where

The vectors and tensors involved in the fourth and fifth integrations of Eq. (62) are given as

1.4.2 General case

The boundary terms added for Side B are given as

where the normal component of the heat conduction part of the viscous flux vectors are taken as

The vectors and tensors involved in the fourth and fifth integrations of Eq. (71) are given as

Element metric tensor

Here provide the element metric tensor in space and in the ST framework from [120], which was based on [116].

1.1 Element metric tensor in space

Components of the Jacobian matrix \(\mathbf {Q}\) are written as

where \(\xi _j\) is the parametric coordinate in jth direction. We first scale it with a matrix \(\mathbf {D}\) to take into account the polynomial order or other factors such as the dimensions of the element domain in the parametric space:

With this vector, we define the element length (see [116]) as

where

Remark 8

From this derivation, what we get with \(\mathbf {D}=\mathbf {I}\) has been used in many methods of calculating the stabilization parameters (see, for example, [2]). In those methods, a scaling factor taking the polynomial order into account is applied to the element length, and here we do the scaling in the parametric space, for each of the parametric directions.

Sweeping over all the directions represented by \(\mathbf {r}\), we obtain the minimum and maximum element lengths:

They are equivalent to

and

where \(\lambda _{\max }\) and \(\lambda _{\min }\) are the maximum and minimum eigenvalues of the argument matrix.

Remark 9

In the implementation, we take measures to keep the calculated element length between \(h_\mathrm {MIN}\) and \(h_\mathrm {MAX}\).

1.2 Element metric tensor in the ST framework

The ST Jacobian matrix is

where \(\theta \) is the parametric coordinate in time, and the mesh velocity \(\mathbf {v}\) is

The ST scaling matrix is given as

and the scaling becomes

The ST metric tensor is defined as

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanai, T., Takizawa, K., Tezduyar, T.E. et al. Compressible-flow geometric-porosity modeling and spacecraft parachute computation with isogeometric discretization. Comput Mech 63, 301–321 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-018-1595-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-018-1595-4