Abstract

Expression of crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) is characterized by extreme variability within and between taxa and its sensitivity to environmental variation. In this study, we determined seasonal fluctuations in CAM photosynthesis with measurements of nocturnal tissue acidification and carbon isotopic composition (δ13C) of bulk tissue and extracted sugars in three plant communities along a precipitation gradient (500, 700, and 1,000 mm year−1) on the Yucatan Peninsula. We also related the degree of CAM to light habitat and relative abundance of species in the three sites. For all species, the greatest tissue acid accumulation occurred during the rainy season. In the 500 mm site, tissue acidification was greater for the species growing at 30% of daily total photon flux density (PFD) than species growing at 80% PFD. Whereas in the two wetter sites, the species growing at 80% total PFD had greater tissue acidification. All species had values of bulk tissue δ13C less negative than −20‰, indicating strong CAM activity. The bulk tissue δ13C values in plants from the 500 mm site were 2‰ less negative than in plants from the wetter sites, and the only species growing in the three communities, Acanthocereus tetragonus (Cactaceae), showed a significant negative relationship between both bulk tissue and sugar δ13C values and annual rainfall, consistent with greater CO2 assimilation through the CAM pathway with decreasing water availability. Overall, variation in the use of CAM photosynthesis was related to water and light availability and CAM appeared to be more ecologically important in the tropical dry forests than in the coastal dune.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) is characterized by a nocturnal CO2 uptake by the enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPc), which represents phase I within the four phases of CAM as defined by Osmond (1978). This nocturnal uptake of CO2 via PEPc forms C4 acids, which are decarboxylated during the daytime and generate an elevated intercellular CO2 concentration when stomata are closed (phase III). Between these two phases, there are transitional periods of net CO2 uptake at the beginning (phase II) and at end (phase IV) of the day, when both PEPc and RUBISCO can contribute to CO2 assimilation (Lüttge 1987; Cushman 2001; Dodd et al. 2002). Environmental factors such as light intensity, relative humidity, nocturnal temperature, and water availability affect the proportion of CO2 uptake at night via PEPc or directly during the day via RUBISCO (Griffiths 1992; Cushman and Borland 2002; Taybi et al. 2002; Jian-Ying et al. 2005).

The nocturnal CO2 uptake mechanism found among CAM species generally improves water-use efficiency because of reduced transpiration rate during the night (Cushman and Borland 2002). One hallmark of CAM plants is the remarkable flexibility of the basic metabolic framework described above, which varies in terms of the proportion of CO2 assimilated through the CAM and C3 pathways, among taxa, and in response to environmental conditions (Holtum and Winter 1999; Holtum 2002; Taybi et al. 2002; Cushman and Borland 2002; Dodd et al. 2002; Winter and Holtum 2007; Winter et al. 2008), and may confer an ecological advantage for surviving in habitats with seasonal variation in resource availability (Griffiths 1992; Cushman and Borland 2002; Lüttge 2004). Therefore, CAM plants are likely to vary in the balance of CO2 assimilation by RUBISCO versus PEPc along environmental gradients, and such variation may provide some advantage over other species within the community.

Investigations of carbon isotopic composition (δ13C) can yield information regarding long-term and daily changes in the proportion of CO2 fixed during the night or day (Griffiths 1992). The 13C/12C ratio is an indicator of these changes in the assimilation of CO2 because the enzyme responsible for net CO2 uptake in the dark, PEPc, discriminates less against 13C than RUBISCO, the enzyme responsible for most net CO2 uptake during the day. The changes in δ13C in CAM plants thus depend on: (1) the contribution of CO2 fixed directly by RUBISCO in the light (Phase II and IV); (2) the proportion of respiratory CO2 fixed during phase I in the dark by PEPc; and (3) the extent of leakage during the decarboxylation (phase III), allowing RUBISCO discrimination to be expressed (Griffiths et al. 1990, 2007; Griffiths 1992). CAM plants with CO2 uptake almost exclusively at night would, thus, be expected to show δ13C values around −11‰, whereas if all the CO2 is fixed directly by RUBISCO the values of δ13C would be approximately −27‰ (O’Leary 1988). A shortcoming of using whole-tissue carbon isotope surveys to obtain an integrated value of the contribution of dark and light CO2 fixation to the total carbon gain is that, in the absence of measurements of acidity or CO2 exchange, it is unclear where C3 ends and CAM begins. Species with values of δ13C characteristic of C3 plants have been reported to obtain up to one-third of their carbon through CAM activity (Winter and Holtum 2002; Silvera et al. 2005; Griffiths et al. 2007).

Many studies document a wide range in the magnitude of CAM expression that can be induced by water limitation, high temperatures, and high light availability in different species (Kluge et al. 2001; Winter and Holtum 2002, 2005; Pierce et al. 2002; Holtum et al. 2004; Winter et al. 2005; Griffiths et al. 2007; Herrera 2009; Silvera et al. 2009; Vargas-Soto et al. 2009). Moreover, ecophysiological surveys are a powerful tool to obtain insights leading to a better understanding of the adaptive significance of CAM (Kluge et al. 1997, 2001). In this paper, we present a comparative survey of CAM activity in three plant communities of the Yucatan Peninsula along a gradient of water availability. This is to our knowledge one of the few comparative ecophysiological investigations of CAM activity of different species in different ecosystems. The aims of the present study were: (1) to determine the relative ecological importance of CAM species as a function of precipitation; (2) to determine seasonal fluctuations in CAM photosynthetic activity through nocturnal acid accumulation in plants growing on a precipitation gradient and in different light microenvironments; (3) to evaluate the extension and degree of CAM activity through isotopic variation in δ13C of bulk photosynthetic tissue and sugars along a precipitation gradient.

Materials and methods

Study site and species

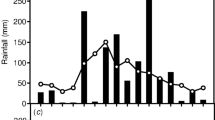

The Yucatan Peninsula experiences a seasonally-dry tropical climate and contains a north–south precipitation gradient of 500–2,000 mm. A marked dry season from March to May, when most of the trees are leafless, is separated from the rainy season between June and October, and an early dry season from November to February, which is often characterized by up to 3-day events of strong winds (>80 km h−1), little rainfall (20–60 mm) and low temperatures (<20°C; Orellana 1999).

This study was conducted in three sites: (1) the coastal dune scrubland of San Benito (21°19′10″N, 89°30′40″W), which receives approximately 500 mm of annual rainfall, and has a mean annual temperature of 26°C (Orellana 1999); (2) Dzibilchaltún, National Park (21°05′N, 89°35′W), a tropical dry deciduous forest with a mean annual rainfall of 700 mm and temperature of 25.8°C (Thien et al. 1982); and (3) Cuxtal Ecological Reserve (20°47′N, 89°49′W), a tropical dry deciduous forest, with a mean annual rainfall of approximately 1,000 mm, and a mean annual temperature of 25.5°C (Chnaid 1998). The sites were selected because of high CAM species diversity and relatively little disturbance compared to ecosystems of the northern Yucatan (Espejel 1987; Rico-Gray et al. 1988; Ceccon et al. 2002; White and Hood 2004).

At each site, species in families with previous reports of CAM (Winter and Smith 1996), such as Agavaceae, Bromeliaceae, Cactaceae and Orchidaceae, were selected for investigation. Only one epiphyte species was selected, Myrmecophila christinae, and all other species were terrestrial (Table 1).

Community structure and relative importance value of CAM species

The point-centered quarter method was used to determine community structure and captures the most abundant species in a rapid and reliable way (Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg 1974). We used two 100-m-long transects and selected 20 sampling points at random in each transect. At each sampling point, four quarters were established through a cross formed by two lines. The distance to the midpoint of the nearest individual from the sampling point was measured in each quarter. For each sampling point, the species identity and the cover or dominance of the individual were recorded. The individuals considered were those that had a minimum height of 10 cm; Poaceae and annual species were not considered. The relative importance value (RIV) was used to estimate the relative importance of plant species in the three communities defined as: RIV = Relative density + Relative coverage + Relative frequency (Skeen 1972; Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg 1974).

Nocturnal tissue acidification

At each study site, ten individuals of each species were randomly selected, five growing at ca. 80% of total daily photon flux density (PFD) and five growing at ca. 30% of total daily PFD, which was measured with gallium arsenide phosphide photodiodes (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ, USA), previously calibrated against a quantum sensor (LI190S; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) connected to a datalogger (CR21X; Campbell Scientific, Logan, UT, USA) and placed 5 m above the ground in a non-shaded location. The minimal distance among individuals was 5 m.

Two samples of one leaf or stem were taken with a cork borer (1.5 cm diameter) at dusk, and before dawn the following day during the rainy (15–18 October 2005), early dry (7–10 February 2006) and dry (25–28 May 2006) seasons. Environmental conditions at the time of sampling were: during the rainy season, a daily average precipitation of 27.4 mm in the three sites (15 October 2005), minimum temperature 20°C (San Benito), maximum temperature 34°C (Dzibilchaltún and Cuxtal); during the early dry season no rainfall during the sampling period and previous week, minimum temperature 10°C (San Benito), maximum temperature 32°C (Cuxtal); during the dry season little rainfall at Cuxtal (3.5 mm) during the sampling period; minimum temperature 22°C (San Benito); maximum temperature 35°C (Cuxtal). Samples were frozen until transported to the laboratory, then boiled in 10 ml of distilled water for 10 min, and, after adding 50 ml of distilled water, ground with a mortar and pestle, and titrated with 0.01 N NaOH to pH 7 (Osmond et al. 1994) measured with an electronic pH meter (Model 744; Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland). Nocturnal tissue acidification (ΔH+) was estimated from the hydrogen ion concentration (H+) at dawn minus H+ at dusk.

Carbon isotopic composition

During the rainy season (18 October 2005), five samples of leaf or stem were taken from the same individuals at the time when the predawn samples for tissue acidity were taken. The samples were dried in an oven at 80°C for 48 h and homogenized to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. Samples for carbon isotopic composition of bulk tissue were prepared as 3-mg samples rolled in tin capsules (Crayn et al. 2001; Pierce et al. 2002; Winter and Holtum 2002).

Whereas carbon isotopic composition (δ13C) of bulk tissue represents the time-integrated proportion of CO2 assimilated through the CAM versus C3 pathway in CAM plants, we also measured the extractable sugar fraction, which more closely reflects the photosynthetic discrimination against 13CO2 over the previous 1–2 days allowing an indication of how plants are responding to environmental conditions over a shorter period (Ehleringer et al. 2004; Hu et al. 2010). The sugar extraction and purification was performed according to Brugnoli et al. (1998) and modified as follows: approximately 50 mg of oven-dried leaf material was mixed with 5 cm3 of distilled de-ionized water (vortex for few seconds), and centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000g. The supernatant was then decanted through ion-exchange resins (Dowex 50WX8-100, 1X2, Cl−-form; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) to isolate the neutral fraction (mostly sugars). After freeze-drying the samples, 0.8–2.0 mg of dried sugars were prepared in sample tins for isotopic analysis. δ13C was determined on an elemental analyzer (ANCA-SL; PDZ Europa, Crewe, UK) interfaced with a continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (model 20/20; PDZ Europa) at the University of California, Berkeley, Center for Stable Isotope Biogeochemistry (CSIB). Long-term external precision for these analyses are ±0.22% for δ13C. The abundance of 13C in each sample was calculated relative to the abundance of 13C in internal standards that had been calibrated against Pee Dee belemnite. Relative abundance was determined using the relationship (Ehleringer et al. 2004): δ13C (‰) = [(13C/12C of sample)/(13C/12C of standard)-1] × 1,000.

Statistical analysis

A three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with ‘repeated measures’ (ANOVAR; Potvin et al. 1990; Valdez-Hernández et al. 2010) was used to compare the tissue acidity among light levels, seasons and species within each site. Differences in carbon isotopic composition among sites and between light levels were tested using a nested ANOVA, where the different light levels were nested within each site, and using mean species values for bulk tissue and sugar δ13C. Means were compared with a Tukey test and all analyses were performed using Statistica v. 7.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). Linear regression was utilized to describe the relationship of both bulk tissue and extracted sugar δ13C values for Acanthocereus tetragonus as a function of annual rainfall.

Results

Relative importance of CAM species

In the 500 mm site (coastal dune scrubland, San Benito), 10% of species had CAM, which represented 19% of the relative importance value (RIV) in the plant community. In this site, one CAM species (Agave angustifolia) was 1 of the 15 species with the highest RIV (16% RIV; Fig. 1a), while Acanthocereus tetragonus and Opuntia dillenii contributed only 3% of the RIV in the community. In both tropical dry deciduous forest communities, 15% of species were CAM and represented 35 and 20% of the RIV for the 700 mm site (Dzibilchaltún) and the 1,000 mm site (Cuxtal), respectively. Four CAM species were among the 16 species with the highest importance value in these two communities: in the 700 mm site, these were Agave angustifolia, Nopalea inaperta, Bromelia karatas and Stenocereus eichlamii; whereas in the 1,000 mm site, these were S. eichlamii, N. inaperta, B. karatas, and Pereskiopsis scandens. Acanthocereus tetragonus was not within the 15 species with the highest RIV, but it was always among the 24 species of most importance in both forest communities (Fig. 1).

Nocturnal tissue acidification

Tissue acidification was significantly different among seasons in the three sites, with the greatest values during the rainy season (P < 0.0001 for the three sites; Table 1). In the 500 mm site, the lowest tissue acidification values were during the dry season, and in both wetter sites, the lowest values were during the early dry season. During the rainy season, tissue acidification was significantly different for plants growing in the two light microclimates in the three communities (P < 0.0001 for the 500 mm site, and P < 0.05 for the 700 mm and the 1,000 mm sites, respectively; Table 1). At the 500 mm site, plants growing at 30% of total daily ambient PFD showed higher acidity values than those growing at 80% of total PFD (P < 0.0001; Table 1). In both forest communities, tissue acidification during the rainy season was greater for plants growing at 80% PFD than plants growing at 30% PFD (P = 0.020 and P = 0.047, for the 700 and 1,000 mm sites, respectively).

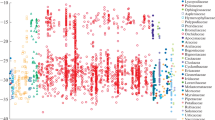

Carbon isotopic composition of bulk tissue fractions

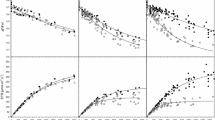

All plants in all sites showed bulk tissue leaf δ13C values typical of strong CAM, less negative than −20‰ (Fig. 2), with the least negative bulk tissue δ13C values (−11 to −15‰) in the 500 mm site (Fig. 2a) and the most negative values (−12 to −19‰) in the 1,000 mm site (Fig. 2c). Plants growing in the 500 mm site were more enriched in 13C (P < 0.05), with mean δ13C of bulk tissue approximately 2‰ less negative than plants growing in the forest communities. There was a significant negative relationship between annual rainfall and leaf δ13C values for Acanthocereus tetragonus, the only species found in all three sites (Fig. 3a). No differences in bulk tissue δ13C values were found between plants growing at 30 and 80% total daily ambient PFD in any of the three sites (P > 0.05).

Carbon isotopic composition of the sugar fraction

Similar to bulk tissue δ13C values, in the 500 mm site, plants had sugar δ13C values 2‰ less negative than plants in the other two sites (P < 0.05). The standard deviation from the mean of the δ13C values of the sugar fraction in each species showed that Acanthocereus tetragonus had greater δ13C variability than the rest of the species (Fig. 4). Similar to bulk tissue, δ13C values of the sugar fraction for Acanthocereus tetragonus showed decreasing enrichment of 13C of sugar with increasing precipitation (Fig. 3b). Moreover, A. tetragonus was the only species that showed significant differences in the δ13C values of sugar between the plants growing at 80 and 30% of total daily PFD in the coastal dune scrubland; plants that had the least negative values of δ13C were those growing at 80% PFD in comparison with plants growing at 30% PFD (P < 0.0001; Fig. 5a). In the other two communities, this species did not show differences in δ13C of sugar between light microenvironments (P > 0.05). Tissue acidification was significantly different between individuals of A. tetragonus growing at 80 and 30% of PFD in the coastal dune scrubland (Fig. 5b); individuals with the lowest acidity values were those growing at 80% PFD (P < 0.0001). No differences in tissue acidity were found between the plants of this species growing in both light conditions in the other two communities (P > 0.05; Fig. 5b).

Mean δ13C values (closed symbols) of sugar ± standard deviation and range (open symbols) of 10 CAM species. Key for the species code: Acanthocereus tetragonus (At), Agave angustifolia (Aa), Bromelia karatas (Bk), Nopalea inaperta (Ni), Stenocereus eichlamii (Se), Pilosocereus gaumeri (Pg), Pereskiopsis scandens (Ps), Opuntia dillenii (Od), Selenicereus donkelaarii (Sd), and Tillandsia dasyliriifolia (Td)

Values of δ13C of sugars (a) and tissue acidity (b) in three populations of Acanthocereus tetragonus in San Benito (circles), Dzibilchaltún (triangles) and Cuxtal (squares) growing at 80% of total daily photon flux density (PFD) (open symbols) or at 30% total PFD (closed symbols) during the rainy season

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that carbon gain by CAM plants along this precipitation gradient was greatest in the wet season, indicating that seasonal water limitation has the potential to reduce carbon gain by approximately 75% at the relatively dry coastal dune site and by 50% in the wetter forest sites, when comparing tissue acidification in the dry season versus wet season. In addition, at the driest site, plants growing at lower light had greater rates of carbon gain, whereas in the two wetter sites, plants growing in the higher light microhabitat had greater rates of carbon gain. These results highlight a shift in the interaction between light and water availability along this gradient, in which we observed that, when water availability increases, plants were able to increase their tissue acidification at higher PFD. In addition, our δ13C data showed greater proportional use of the nocturnal CO2 uptake of the CAM species at the driest site (Fig. 2). Moreover, species importance values and the proportion of CAM species in the communities increased from the coastal dune to the tropical dry forests, suggesting a more favorable balance of light and water availability for CAM performance in the wetter, forested communities.

Tissue acidity is an indirect way to measure nocturnal CO2 uptake, including direct CO2 uptake and CO2 produced during respiration and re-assimilation. Therefore, an increase in tissue acidity would indicate an increase in the CO2 uptake (Nobel 1988, 1991; Osmond et al. 1994). Other CAM species also show an enhancement in their net CO2 uptake and increase tissue acidity when well watered and a reduction of these two processes when droughted (Andrade et al. 2007, 2009). The reduction of tissue acidity during the dry season can be caused by higher nocturnal temperatures and greater water deficits together with higher PFD levels than during the rainy season (Cervera et al. 2007; Andrade et al. 2009). To avoid excess transpiration during the dry season, CAM species tend to show maximal stomatal opening later in the night reducing the amount of nocturnal increase of tissue acidity (Nobel 1985a, b, 1988; Nobel et al. 1991; Andrade and Nobel 1997; Lu et al. 2003; Cervantes et al. 2005; Cervera et al. 2007). Conversely, the reduction of tissue acidity during the early dry season could be caused by the reduction in the PFD (30 mol m−2 day−1) in comparison with that of the rainy and dry seasons (35 and 40 mol m−2 day−1, respectively). Although it has been reported that, for several desert CAM species, nocturnal acid accumulation increases up to a total daily PFD of about 30 mol m−2 day−1 and any reduction in PFD reduces net CO2 uptake (Nobel 1988), lower water vapor pressure deficits in our study sites than in the desert could increase that PFD limit, allowing the plants to use more light without losing more water.

In the 500 mm site, plants growing at 30% of the total daily ambient PFD had greater tissue acidification than plants growing at 80% ambient PFD (Table 1). Nevertheless, in both forest communities, the greatest increase in tissue acidity was for plants growing at 80% PFD. These differences among plants of the three sites are likely due to differences in soil water potentials and water vapor pressure deficits. For example, after 30 days of drought during the dry season, soil water potential 15 cm below the surface was −22.4 ± 2.3 MPa for a coastal dune scrubland and −19.8 ± 1.6 MPa for a tropical dry deciduous forest (Cervera et al. 2007). In addition, in some CAM species, under light-saturating conditions, an increase in the photosynthetic capacity as a response to growth in high light without a proportional increase in the malate supply would predispose some plants to photoinhibition, causing drought stress to increase the negative effects of the high radiation (Skillman and Winter 1997). In our study, during the dry season, most species of the coastal dune site showed the lowest tissue acidity values (Table 1, Fig. 5) and less negative δ13C values than all other species for the two communities, indicating stomatal closure during phases II and IV of the CAM cycle and no contribution of RUBISCO to CO2 uptake.

CAM species that showed significant differences in the tissue acidity growing in the two light microenvironments also had the highest relative importance value in the three communities. One exception was Acanthocereus tetragonus (Fig. 1), which was the only species in the three communities with strong CAM photosynthesis and a high photosynthetic plasticity in the coastal dune. It has been proposed that, given the range in the magnitude of CAM expression that can be induced by water limitation in different species, the ecological significance of CAM induction would depend on its relative importance as a survival mechanism, rather than the direct contribution to growth and productivity of the species (Griffiths 1992; Cushman and Borland 2002; Lüttge 2004). Kluge et al. (2001) found that CAM species of Madagascar with the highest photosynthetic plasticity were the species most widely distributed across the island, and thus occupied a greater variety of environments, compared to CAM species with low photosynthetic plasticity, which occupied a more restricted set of environments.

CAM plants in the three communities showed bulk tissue δ13C values typical of strong CAM (δ13C values less negative than −20‰; Holtum et al. 2004; Silvera et al. 2005), but the δ13C values in plants from the coastal dune scrubland were 2‰ less negative than those from plants of the forest communities (Fig. 2). The bulk tissue and sugar δ13C values for Acanthocereus tetragonus, which occurred in the three sites, showed a significant negative relationship with rainfall (Fig. 3). These data suggest that plants at drier sites decreased transpiration and stomatal conductance relative to photosynthesis, which would lead to the measured increase in δ13C values. Moreover, the duration of the phase II of CAM decreases under water stress (Griffiths 1992), which would also decrease the isotope discrimination, leading to less negative δ13C values. Similar results have been found in terrestrial plants from desert and tropical dry forest, and for epiphytes in a tropical cloud forest and three different secondary tropical dry forests where the carbon isotope ratios also increased with decreasing water availability (Ehleringer and Cooper 1988; Mooney et al. 1989; Hietz et al. 1999; Goode et al. 2010).

It has been proposed that the flexibility of CAM provides an advantage for acquisition of ecological niches (Lüttge 2004; Herrera 2009). In the present study, although all the species investigated in the three communities showed δ13C values typical of strong CAM, one species, A. tetragonus, which inhabited all three communities, showed the highest variability in δ13C values (Fig. 4). Members of the family Cactaceae have been considered as constitutive or obligate CAM species even at their early stages (Hernández-González and Briones-Villarreal 2007); although some studies suggest that the contribution of CAM to total carbon gain is small during the first developmental stages (Nobel 1988; Winter et al. 2008). The high variability of the strong CAM species, A. tetragonus, suggests that some cacti are able to respond to changes in the environment and inhabit more environments than other cacti. More detailed field and laboratory studies on different life stages of these strong CAM plants would be required to fully understand their ecological role in these tropical plant communities.

References

Andrade JL, Nobel PS (1997) Microhabitats and water relations of epiphytic cacti and ferns in a lowland neotropical forest. Biotropica 29:261–270

Andrade JL, De la Barrera E, Reyes-García C, Ricalde MF, Vargas-Soto G, Cervera JC (2007) El metabolismo ácido de las crasuláceas: diversidad, fisiología ambiental y productividad. Bol Soc Bot Mex 81:37–50

Andrade JL, Cervera JC, Graham EA (2009) Microenvironments, water relations, and productivity of CAM plants. In: De la Barrera E, Smith WK (eds) Perspectives in biophysical plant ecophysiology. A tribute to Park S. Nobel. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico

Brugnoli E, Hubick KT, von Caemmerer S, Wong SC, Farquhar GD (1998) Correlation between the carbon isotope discrimination in leaf starch and sugars of C3 plants and the ratio of intercellular and atmospheric partial pressures of carbon dioxide. Plant Physiol 88:1418–1424

Ceccon E, Olmsted I, Vázquez-Yanes C, Campo J (2002) Vegetation and soil properties in two tropical dry forest of differing regeneration status in Yucatan. Agrociencia 36:621–631

Cervantes SE, Graham EA, Andrade JL (2005) Light microhabitats, growth and photosynthesis of an epiphytic bromeliad in a tropical dry forest. Plant Ecol 179:107–118

Cervera JC, Andrade JL, Graham EA, Durán R, Jackson PC, Simá JL (2007) Photosynthesis and optimal light microhabitats for rare cactus, Mammillaria gaumeri, in two tropical ecosystems. Biotropica 39:620–627

Chnaid GD (1998) Cavernas y Cenotes de la Reserva Ecológica de Cuxtal. Ayuntamiento de Mérida, Mexico

Crayn DM, Smith JAC, Winter K (2001) Carbon-isotope ratios and photosynthetic pathways in the Rapataceae. Plant Biol 3:569–575

Cushman JB (2001) Crassulacean acid metabolism. A plastic photosynthetic adaptation to arid environments. Plant Physiol 127:1439–1448

Cushman JB, Borland AM (2002) Induction of Crassulacean acid metabolism by water limitation. Plant Cell Environ 25:295–310

Dodd AN, Borland AM, Haslam RP, Griffiths H, Maxwell K (2002) Crassulacean acid metabolism: plastic, fantastic. J Exp Bot 53:569–580

Ehleringer JR, Cooper TA (1988) Correlations between carbon isotope ratio and microhabitat in desert plants. Oecologia 76:562–566

Ehleringer JR, Crayn DM, Lott M (2004) Stable isotope methods. Stable isotope ratio facility for environmental research. University of Utah, Stable isotope ecology course, Salt Lake City

Espejel I (1987) A phytogeographical analysis of coastal vegetation in the Yucatan. J Biogeogr 14:499–519

Goode LK, Erhardt EB, Santiago LS, Allen MF (2010) δ13C soluble sugars in Tillandsia epiphytes vary in response to shifts in habitat. Oecologia (in press)

Griffiths H (1992) Carbon isotope discrimination and the integration of carbon assimilation pathways in terrestrial CAM plants. Plant Cell Environ 15:1051–1062

Griffiths H, Broadmeadow MSJ, Borland AM, Hetherington CS (1990) Short-term changes in carbon-isotope discrimination identify transitions between C3 and C4 carboxylation during crassulacean acid metabolism. Planta 181:604–610

Griffiths H, Cousin AB, Murray R, von Caemmerer S (2007) Discrimination in dark. Resolving the interplay between metabolic and physical constraints to phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase activity during the crassulacean acid metabolism cycle. Plant Physiol 143:1055–1067

Hernández-González O, Briones-Villarreal O (2007) Crassulacean acid metabolism photosynthesis in columnar cactus seedlings during ontogeny: the effect of light on nocturnal acidity accumulation and chlorophyll fluorescence. Am J Bot 94:1344–1351

Herrera A (2009) Crassulacean acid metabolism and fitness under water deficit stress: if not for carbon gain, what is facultative CAM good for? Ann Bot 103:645–653

Hietz P, Wanek W, Popp M (1999) Stable isotopic composition of carbon and nitrogen and nitrogen content in vascular epiphytes along an altitudinal transect. Plant Cell Environ 22:1435–1443

Holtum JAM (2002) Crassulacean acid metabolism: plasticity in expression, complexity of control. Funct Plant Biol 29:657–661

Holtum JAM, Winter K (1999) Degrees of crassulacean acid metabolism in tropical epiphytic and lithophytic ferns. Plant Physiol 26:749–757

Holtum JAM, Aranda J, Virgo A, Gehrig HH, Winter K (2004) δ13C values and crassulacean acid metabolism in Clusia species from Panama. Trees 18:658–668

Hu J, Moore DJP, Monson RK (2010) Weather and climate controls over the seasonal carbon isotope dynamics of sugars from subalpine forest trees. Plant Cell Environ 33:35–47

Jian-Ying MA, Chen T, Qiang WY, Wang G (2005) Correlation between foliar stable carbon isotope composition and environmental factors in desert plant Reaumuria soongorica (Pall) Maxim. Acta Bot Sin 9:1065–1073

Kluge M, Vinson B, Ziegler H (1997) Ecophysiological studies on orchids of Madagascar: incidence and plasticity of crassulacean acid metabolism in species of the Agraecum Bory. Plant Ecol 135:43–57

Kluge M, Razanoelisoa B, Brulfert J (2001) Implications of genotypic diversity and phenotypic plasticity in the ecophysiological success of CAM plants, examined by studies on vegetation of Madagascar. Plant Biol 3:214–222

Lu Q, Qui N, Lu Q, Wang B, Kuang T (2003) PSII photochemistry, thermal energy dissipation, and the xanthophyll cycle in Kalanchoe daigremontiana exposed to a combination of water stress and high light. Physiol Plant 118:173–182

Lüttge U (1987) Carbon dioxide and water demand: crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), a versatile ecological adaptation exemplifying the need of integration in ecophysiological work. New Phytol 106:593–629

Lüttge U (2004) Ecophysiology of crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM). Ann Bot 93:629–657

Mooney HA, Bullock SH, Ehleringer JR (1989) Carbon isotope ratios of a tropical dry forest in Mexico. Funct Ecol 3:137–142

Mueller-Dombois D, Ellenberg H (1974) Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. Wiley, New York

Nobel PS (1985a) PAR, water, and temperature limitations on the productivity of cultivated Agave fourcroydes (Henequen). J App Ecol 22:157–173

Nobel PS (1985b) Water relations and carbon dioxide uptake of Agave deserti—special adaptation to desert climates. Desert Plants 7:51–56

Nobel PS (1988) Environmental biology of agaves and cacti. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Nobel PS (1991) Tansley Review No 32. Achievable productivities of certain CAM plants: basis for high values compared with C3 and C4 plants. New Phytol 119:183–205

Nobel PS, Loik ME, Meyer RW (1991) Microhabitat and diel tissue acidity changes for two sympatric cactus species differing in growth habitat. J Ecol 79:167–182

O’Leary MH (1988) Carbon isotopes in photosynthesis. Fractionation techniques may reveal new aspects carbon dynamics in plants. BioScience 38:328–336

Orellana R (1999) Evaluación climática. In: Garcia A, Cordova J (eds) Atlas de procesos territoriales de Yucatán. Facultad de Arquitectura, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Mérida, pp 163–182

Osmond CB (1978) Crassulacean acid metabolism: a curiosity in context. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 29:547–557

Osmond CB, Adams WW III, Smith SD (1994) Crassulacean acid metabolism. In: Pearcy RW, Ehleringer JR, Mooney HA, Rundel PW (eds) Plant physiological ecology. Field methods and instrumentation. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 255–280

Pierce S, Winter K, Griffiths H (2002) Carbon isotope ratio and extent of daily CAM use by Bromeliaceae. New Phytol 156:75–83

Potvin C, Lechowics MJ, Tardif S (1990) The statistical analysis of ecophysiological response curves obtained from experiments involving repeated measures. Ecology 71:1389–1400

Rico-Gray V, Puch A, Simá P (1988) Composition and structure of a tropical dry forest in Yucatan, Mexico. Int J Ecol Environ Sci 14:21–29

Silvera K, Santiago L, Winter K (2005) Distribution of crassulacean acid metabolism in orchids of Panama: evidence of selection for weak and strong modes. Funct Plant Biol 32:397–407

Silvera K, Santiago LS, Cushman JC, Winter K (2009) Crassulacean acid metabolism and epiphytism linked to adaptive radiations in the Orchidaceae. Plant Physiol 149:1838–1847

Skeen J (1972) An extension of the concept of importance value in analyzing forest communities. Ecology 54:655–656

Skillman JB, Winter K (1997) High photosynthetic capacity in a shade-tolerant crassulacean acid metabolism plant. Plant Physiol 113:441–450

Taybi T, Cushman JC, Borland AM (2002) Environmental hormonal and circadian regulation of crassulacean acid metabolism expression. Funct Plant Biol 20:669–678

Thien LB, Bradburn AS, Welden AL (1982) The woody vegetation of Dzibilchaltun a Maya archeological site in Northwest Yucatan Mexico. Middle American Research Institute,Tulane University, New Orleans

Valdez-Hernández M, Andrade JL, Jackson PC, Rebolledo-Vieyra M (2010) Phenology of five tree species of a tropical dry forest in Yucatan, Mexico: effects of environmental and physiological factors. Plant Soil 329:155–171

Vargas-Soto JG, Andrade JL, Winter K (2009) Carbon isotope composition and mode of photosynthesis in Clusia species from Mexico. Photosynthetica 47:33–40

White DA, Hood CS (2004) Vegetation pattern and environmental gradients in tropical dry forest of northern Yucatan Peninsula. J Veg Sci 15:151–160

Winter K, Holtum JAM (2002) How closely do the δ13C values of crassulacean acid metabolism plants reflect the proportion of CO2 fixed during day and night±. Plant Physiol 129:1843–1851

Winter K, Holtum JAM (2005) The effects of salinity, crassulacean acid metabolism and plant age on the carbon isotope composition of Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L., halophytic C3-CAM species. Planta 222:201–209

Winter K, Holtum JAM (2007) Environment or development? Lifetime net CO2 exchange and control of the expression of crassulacean acid metabolism in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum. Plant Physiol 143:98–107

Winter K, Smith JAC (1996) An introduction to crassulacean acid metabolism: biochemical principles and biological diversity. In: Winter K, Smith JAC (eds) Crassulacean acid metabolism. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–13

Winter K, Aranda J, Holtum JAM (2005) Carbon isotope composition and water-use efficiency in plants with crassulacean acid metabolism. Funct Plant Biol 32:381–388

Winter K, Garcia M, Holtum JAM (2008) On the nature of facultative and constitutive CAM: environmental and developmental control of CAM expression during early growth of Clusia, Kalanchoë, and Opuntia. J Exp Bot 59:1829–1840

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant Fondo Sectorial SEP-CONACYT 48344/24588 to J. L. A., a University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States grant to L. S. S., and a Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Mexico Fellowship to M. F. R. Special thanks go to Caroline DeVan for laboratory assistance with sugar extractions and Eduardo Balam for providing the environmental data, and to Katia Silvera, Lee Buckingham, Alejandra Martínez-Berdeja, Casandra Reyes, Olivia Hernández and Claudia González-Salvatierra for comments on a draft of the manuscript. This study complies with the current laws of Mexico.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Hermann Heilmeier.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ricalde, M.F., Andrade, J.L., Durán, R. et al. Environmental regulation of carbon isotope composition and crassulacean acid metabolism in three plant communities along a water availability gradient. Oecologia 164, 871–880 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-010-1724-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-010-1724-z