Abstract

Seasonal variations in seawater temperature require extensive metabolic acclimatization in cold-blooded organisms inhabiting the coastal waters of Europe. Given the energetic costs of acclimatization, differences in adaptive capacity to climatic conditions are to be expected among distinct populations of species that are distributed over a wide geographic range. We studied seasonal variations in the metabolic adjustments of two very common bivalve taxa at European scale. To this end we sampled 16 populations of Mytilus spp. and 10 Macoma balthica populations distributed from 39° to 69°N. The results from this large-scale comprehensive comparison demonstrated seasonal cycles in metabolic rates which were maximized during winter and springtime, and often reduced in the summer and autumn. Studying the sensitivity of metabolic rates to thermal variations, we found that a broad range of Q 10 values occurred under relatively cold conditions. As habitat temperatures increased the range of Q 10 narrowed, reaching a bottleneck in southern marginal populations during summer. For Mytilus spp., genetic-group-specific clines and limits on Q 10 values were observed at temperatures corresponding to the maximum climatic conditions these geographic populations presently experience. Such specific limitations indicate differential thermal adaptation among these divergent groups. They may explain currently observed migrations in mussel distributions and invasions. Our results provide a practical framework for the thermal ecophysiology of bivalves, the assessment of environmental changes due to climate change and its impact on (and consequences for) aquaculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A fundamental step forward in predicting the ecological and economic consequences of climate change would be to identify the mechanistic link between the physiology of species and climatic variations. How and to what extent climatic variations cause stress in eurythermal bivalve species is still not fully understood and is expected to differ among taxa. In general, for organisms that maintain their body temperature by absorbing heat from the environment (ectotherms), temperatures that are too high can act as a stressor in two ways. On the one hand, it may cause the denaturing of sensitive proteins. This damage can be minimized by the actions of heat-shock proteins, which increase the thermostability of proteins and chaperone cellular processes (Feder and Hofmann 1999; Lyons et al. 2003). On the other hand, excessive temperatures may cause oxygen limitation, due to a limited respiratory capacity, resulting in a maximum respiration rate at a specific temperature, beyond which anaerobic metabolic pathways are utilized and respiration rates usually drop drastically (Pörtner 2001, 2002). The temperature that corresponds to this respiratory maximum is referred to as the breakpoint temperature. Since breakpoint temperatures tend to correlate with the maximum habitat temperatures of several marine ectotherms (Somero 2002), climate-change-induced shifts in the distributions of these species may be due to their respiratory limitations.

The metabolic rate of an ectotherm is proportional to its respiration rate. To remain energy-efficient, and for protection against oxygen shortage during the warmer seasons, organisms need to adjust their metabolic energy requirements to their maximum food uptake and oxygen consumption rate. Seasonal variation in the respiratory response to temperature reveals how organisms adjust throughout the annual cycle. While several terrestrial and aquatic mollusks apply the strategy of metabolic down-regulation during the summer (Buchanan et al. 1988; McMahon 1973; McMahon and Wilson 1981; Storey and Storey 1990; Wilson and Davis 1984), others do not (McMahon et al. 1995). The level of metabolic down-regulation is also reflected by the temperature quotient (Q 10) of the metabolic rate, i.e., the sensitivity of the organisms’ metabolism to changes in body temperature. Experimental work performed by Widdows (1976) has demonstrated that when thermal fluctuations approach and exceed breakpoint temperatures, this sensitivity usually decreases. Such reduced sensitivities have been found for field populations of M. edulis (Newell 1969) and M. balthica (Wilson and Elkaim 1991) sampled from high-shore habitats in summertime. Taken together, the thermal sensitivity of the metabolic rate (Q 10) is expected to decrease towards the warm end of the species distribution range.

Lately, invasions (Geller 1999; Wonham 2004) and northward introgression (Luttikhuizen et al. 2002) have been reported for Mytilus spp., and a range contraction for M. balthica (Hummel et al. 2000). Aiming to bridge the gap between the observed migrations of these species and the changing climate in Europe, we studied seasonal adjustments to temperature in bivalve metabolism at the European scale, from 39° to 69°N. The analysis of patterns in the extent of metabolic acclimatization across widely distributed populations will reveal how core populations differ from marginal populations, presenting species-specific responses to cold winters and hot summers near the upper and lower edges of temperature-induced distribution ranges. Such latitudinal gradients may provide a powerful tool that can be used to understand the temperature-dependent distributions of species and to predict their adaptive tolerance to climate change. In macrophysiological studies, the possibility of differential adaptation to regional climates among distinct populations should be taken into account. Based on neutral genetic variation, both European mussels and clams can be subdivided into three main genetic groups (Hummel 2006; Daguin et al. 2001; Luttikhuizen et al. 2003; Skibinski 1985). Uncertainty exists about the nomenclature of European Mytilus species. Traditionally, mussels from the Mediterranean Sea and the coast of the Iberian Peninsula are referred to as Mytilus galloprovincialis (Lamarck). Mussels from the English Channel, the North Sea coast, and the Atlantic coast of Norway and Iceland are named Mytilus edulis (L.), and the mussels from the Central Baltic Sea are called Mytilus trossulus (Gould), which is based upon their genetic resemblance to Mytilus trossulus from the Atlantic coast of Canada (Varvio et al. 1988). However, the morphological characteristics of the different holotypes do not diagnostically separate the three genetic groups found in European mussels. In addition, broad hybridization zones (Daguin et al. 2001) and deep introgressions (Luttikhuizen et al. 2003) have been reported; a genetic characteristic of a single species with separated clades. To avoid confusion, we will not use these species names in this study, but rather refer to them as Mytilus spp., with reference to their geographic distributions, i.e., a Baltic Sea group, a North Sea group, and a Mediterranean Sea and Bay of Biscay group. Also, different genetic groups have been distinguished for M. balthica (Hummel 2006; Luttikhuizen et al. 2003) that have never been described as different species. The coupling of phylogenetic and ecophysiological analyses is urgently needed to understand and predict current and future migrations of these bivalve taxa and their clades.

Methods

Fieldwork

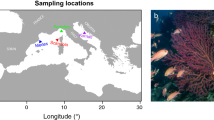

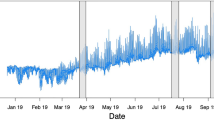

To study the marginal and core populations of both taxa, including different genetic groups, we defined 21 research sites of interest along the European coastline, and sampled 11 M. balthica populations and 16 Mytilus spp. populations, respectively. All sampling stations are numbered (1–21) in Fig. 1. Whenever a station name is mentioned in this text, its number is given between parentheses. The sampling stations were located in the coastal areas of the different sea basins that represent much of the European coastline (including the Mediterranean Sea, the Bay of Biscay, the North Sea and the Baltic Sea), and a variety of microhabitats. The sampling stations in the Mediterranean Sea are characterized by a high and stable salinity (38–40 PSU). In the Bay of Biscay and North Sea estuaries, the ambient salinity at the sampling stations fluctuated, generally varying between ∼35 and ∼25 PSU. Due to elevated river runoff, oligohaline conditions may have occurred occasionally at these stations. The Baltic Sea stations were distributed along the Baltic salinity gradient. While the ambient salinity is still ∼15 PSU in the Mecklenburg Bight (7), it is around 6–7 in the Gulf of Gdansk (6) and Askö (5), and has decreased to 3 PSU in Umeå (3). Although high and low peak temperatures occur at the intertidal sampling stations in the Bay of Biscay and the North Sea, water temperatures were intermediate compared to the warmer Mediterranean Sea and the colder Baltic Sea sites (Fig. 2). In summer, the Baltic Sea warms rapidly, reaching temperatures that are comparable to North Sea conditions. In the tidal estuaries of the Bay of Biscay and the North Sea, sampling was carried out at mid-shore level. Lacking significant tidal movements, Baltic Sea populations of Mytilus spp. and M. balthica, and Mediterranean Sea populations of Mytilus spp. were sampled at a water depth of 0.5–1.0 m. During the period July 2003–May 2005 16 populations (i.e., 10 Mytilus spp. and 6 M. balthica) were visited seasonally and the others only once or twice. During each sampling occasion, mussels were sampled from hard substrate, and clams were sieved from the sediment. For Mytilus spp. populations, mean shell lengths ranged from 28 mm (SD: 2.0) for specimens sampled in the Gulf of Gdansk (6) to 33 mm (SD: 3.5) for mussels sampled from the Santa Giusta Lagoon (21). Mean shell lengths of mussels collected from the other populations was in the same range, and standard deviations were <3.5. About 95% of all sampled mussels fell within a size range of 25–35 mm. For M. balthica mean shell lengths ranged from 12 mm (SD: 1.5) for clams sampled from the Mecklenburg Bight (7) to 16 mm (SD: 1.8) for clams sampled at Point d’Aiguillon (15). Mean shell lengths of all other clam populations were within this range, standard deviations did not exceed 2.8 mm, and 95% of all sampled clams fell within the size range of 10–19 mm. After sampling, the collected animals were stored in foam boxes (clams were offered sediment from the field to bury) and transported to a nearby laboratory, where they were kept in (constantly aerated) aquaria, under ambient field conditions (±3 °C). Measurements were carried out within 24 h after sampling.

Map of research area with 21 research sites. The coastal area is subdivided into three parts representing the approximate distributions of the three genetic groups found in Mytilus spp. and M. balthica. Light gray indicates the Baltic Sea group, medium gray the North Sea group and dark gray the Mediterranean Sea and Bay of Biscay group (hybridization and introgression zones are not indicated). The white and the gray circles represent mussel and clam populations, respectively (see legend). Site no./name: 1, Rykyavik; 2/3, Umeå a/b; 4, Fallvikshamn; 5, Askö; 6, Gulf of Gdansk; 7, Lomma; 8, Mecklenburg Bight; 9, Grevelingenmeer; 10, Westerschelde estuary; 11, Granville; 12, Le Vevier; 13, Brest; 14, Loire estuary; 15, Point d’Aiguillon; 16, Bidasoa estuary; 17, Mundaka estuary; 18, Vias plage; 19, Marseille; 20, Gulfo di Oristano; 21, Santa Giusta lagoon

Annual sea surface temperature (SST) regimes for the sampling stations in the Baltic Sea, the North Sea, the Bay of Biscay, and the Mediterranean Sea. Lines and error bars represent monthly averages and standard deviations, based on measurements taken by satellite twice daily, at 9 a.m. and 2 p.m., during the period 2003–2005. This data were taken from the NASA JPL website (NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory 2005)

Temperature profiles

Field temperature profiles were obtained between April 2004 and May 2005 with temperature loggers (HOBO Water Pro®, Onset Computers, Bourne, MA, USA) at research sites 5, 7, 9, 10, 15, 16 and 18, with a resolution of one measurement per 30 min. The loggers were positioned in the direct vicinity of the animals. Logger output was compared with the sea surface temperature (SST) profiles obtained by satellite (NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory 2005). Mean habitat temperature of the shallow water and intertidal habitats showed a constant relation with SST. In summer SST was about two degrees lower than the mean values calculated from the logger data at all sites, while in winter the SST was slightly lower for the Atlantic and Mediterranean sites. For the Baltic Sea sites, winter SSTs were similar to the logger data. Using the relation between SST and logger data, we estimated the acclimatization temperature of each mussel and clam population for each sampling occasion. This acclimatization temperature is defined in this study as the mean water temperature for the period of 30 days before sampling. We assume that this is a proper indication of the temperature to which the animals should be well adjusted.

Respiration rates

Within 24 h after sampling, groups of 3–6 mussels and 7–15 clams were gently removed from their aquaria, and without further acclimation transferred to respiration chambers of volume 264 and 154 ml, respectively. The chambers were positioned in a thermostated tank to maintain a constant temperature during the incubations (±0.3 °C). The chambers were filled with filtered habitat water, previously aerated to 100% oxygen saturation. Chamber lids contained Clark-type electrodes to record the change in oxygen tension in the water. In this way, 2–6 replicate measurements were taken per population and temperature after each sampling occasion. Control measurements were carried out using the same experimental setup, without animals. The total number of M. balthica specimens used from the populations that were sampled seasonally ranged from 475 from the Westerschelde estuary (10) to 685 from the Mecklenburg Bight (8). For Mytilus spp. the number of experimental animals ranged from 104 from Point d’Aiguillon (15) to 322 from Askö (5). To avoid light-induced stress in M. balthica, the chambers were made out of tanned Plexiglas. Respiration rates were measured at 3, 10, 17, 24 and 31 °C. Measurements continued until the oxygen tension in the chambers had decreased by 20–30%. After each measurement, experimental animals were frozen at −20 °C and subsequently lyophilized for 72 h to a stable weight. From the dried specimens, valves were removed and the soft tissue dry-weights determined to the nearest mg, after which the mass-specific respiration rates and the temperature quotients were calculated. In addition, we estimated the respiration rates and Q 10 values at the acclimatization temperature, per population, per season. Both, respiration rates and Q 10 values were based on the rates that corresponded to the seven-degree temperature interval (for instance 10–17 °C) nearest to the acclimatization temperature. The respiration rates were assessed by linear interpolation, and the Q 10 values were calculated with the following equation: \( {\text{Q}}_{{10}} = {\left( {k_{2} /k_{1} } \right)}^{{{10} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{10} {(t_{2} - t_{1} )}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {(t_{2} - t_{1} )}}} \). Here k 2 and k 1 are the respiration rates measured at the higher and the lower temperatures, t 2 and t 1, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The following working hypothesis was formulated: H0: “Season” or “genetic group” have no effect on the metabolic temperature dependence of M. balthica or Mytilus spp. Because temperature is not the only the factor limiting ectotherm metabolism, commonly used statistical methods such as correlations and regressions are not very well suited for testing this relationship (Blackburn et al. 1992; Cade et al. 1999; Thompson 1996). Estimating the function along the upper edge of this distribution would describe the evolutionary relation between temperature and metabolism in our species. Data points scattered below this “slope of upper bounds” (Blackburn et al. 1992) are responses induced by other limiting factors. To estimate this slope of maximum respiration rate at a given temperature, we carried out a main axis regression analysis (after Thompson et al. 1996). The first step in this is a general regression through all data points. Subsequently, the data are divided into points that fall below and above the line of least squares. All data points that were found above are then used to fit a second regression that again divides the data into two subsets; etc. This was repeated three times. The regression lines were forced through the x, y point (−2, 0), assuming that at the approximate freezing point of seawater bivalve aerobic metabolism is near to zero. The final regression line for M. balthica populations was based on 12 data points, with an r 2 of 0.95. For Mytilus spp. populations, the final regression was based on seven data points with an r 2 of 0.99. The distance between measured respiration rates and this upper slope describes the extent of metabolic down-regulation in the populations. These rate-deviations (distances) were estimated for all populations and used for statistical comparison. ANOVAs based on rate deviations were carried out with “season” or “genetic group” as independent variables. For the “genetic group” analysis, only data points from the temperature range at which all three groups were sampled were included, i.e., the temperature range for the “genetic group” comparison for M. balthica was 9–18 °C, and for Mytilus ssp. 9–15 °C. Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test was used to test for specific differences among seasons or genetic groups.

Results

Respiration rates at experimental temperatures

For each population sampled seasonally, mean respiration rates at experimental temperatures are given in Fig. 3 for Mytilus spp. and in Fig. 4 for M. balthica. Standard deviations among replicate measurements were usually less than 20% of mean values at experimental temperatures near ambient conditions. At high experimental temperature (31 °C), variation among replicate measurements could be higher, with standard deviations occasionally exceeding 50% of the mean values. This was caused by the fact that some groups of specimens exhibited high respiration rates, while other groups consumed almost no oxygen.

Seasonal variation in the respiratory response to an experimental temperature range for ten European Mytilus spp. populations. Station names and degrees north are given in the graphs. Numbers in square boxes refer to the station names presented in Fig. 1. See legend for explanation of the symbols

Seasonal variation in the respiratory response to an experimental temperature range for six European M. balthica populations. Station names and degrees north are given in the graphs. Numbers in square boxes refer to the station names presented in Fig. 1. See legend for explanation of the symbols

The respiration rate of mussels usually declined between 24 and 31 °C (Fig. 3). Exceptions were some cold-acclimatized populations that showed maximum rates between 17 and 24 °C [e.g., the Askö (5), Gulf of Gdansk (6), and Grevelingenmeer (9) populations sampled in January]. Peaks in respiration rates between 1.5 and 2.5 (mg O2/g (dry weight)/h) at 24 °C were frequently observed in springtime (April–May) and occasionally in other seasons. Respiration rates never exceeded 1.5 (mg O2/g (dry weight)/h) in mussels from the Mecklenburg Bight (6) and the Gulf of Gdansk (5).

The highest respiration rates for the M. balthica specimens were mainly observed at 31 °C; the maximum temperature applied in this study (Fig. 4). Especially in the populations from the Westerschelde estuary (10) and Point d’Aiguillon (15), respiration rates never decreased at high experimental temperatures. However, in the Baltic populations, outside the summer period maximum rates were observed at a lower experimental temperature. In Umeå (3), respiration rates measured in January and April declined at experimental temperatures exceeding 10–17 °C.

Respiration rates at acclimatization temperatures

The respiration rates of both taxa increased with acclimatization temperature (Fig. 5). In winter and springtime, deviations from the upper edge slope were small for both Mytilus spp. and M. balthica. At acclimatization temperatures of >12 °C, an increasing number of data points were scattered at increasing distance from the upper edge slope, and the seasonal comparisons (ANOVA + Bonferroni) revealed that rate deviations were mainly restricted to measurements taken in summer and autumn (see column bar plots, superimposed in Fig. 5A,B). These data also revealed genetic group specific differences between the respiration rate and the acclimatization temperature for Mytilus spp. (P < 0.05); (Fig. 5C). Maximum acclimatized respiration rates occurred between 8 and 14 °C in the Baltic Sea group, 15–19 °C in the North Sea group and 20–24 °C in the Mediterranean Sea and Bay of Biscay group. The rate deviations found for the Mediterranean Sea and Bay of Biscay group differed significantly from those found for the Baltic Sea group. Several data points related to the North Sea group were found to fit the reaction norm of the Mediterranean Sea and Bay of Biscay group between 15 and 20 °C. Thus, the rate deviations of these two groups could not be distinguished (P > 0.05). No genetic group specific differentiation was observed for M. balthica (Fig. 5D).

Respiration rates as a function of the acclimatization temperature. The black lines are the upper edge slopes. These graphs include measurements from all research sites presented in Fig. 1. In A and B, different labels represent different sampling seasons (see legend in A). In B and C respiratory response to temperature is presented per genetic group. The gray diamonds, white triangles and black circles represent the Baltic Sea group, the North Sea group and the Mediterranean Sea and Bay of Biscay groups, respectively. Superimposed are the rate deviations calculated per season and per genetic group, in which BS indicates the Baltic Sea group, NS the North Sea group, MS the Mediterranean Sea group and BC the Bay of Biscay group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 refer to the statistical differences for a given season compared to “January” in A and B and for a given group compared to “BS” in C and D

Thermal sensitivity of the metabolic rate

Seasonal variation in thermal sensitivity of the metabolic rate shows that Q 10 values of greater than four were exclusively found in winter and spring (Fig. 6). For M. balthica populations, such high Q 10 values were found at low (January) and high (April) latitudes. In April, Q 10 values decreased significantly with latitude. Maximum Q 10 did not exceed 3.0 in July and October. July values were about one for clams from the Westerschelde estuary (10) and Point d’Aiguillon (15). The clam population at Askö (5) also exhibited relatively low values (<2). Q 10 values of greater than four were only observed in January and April for mussels (Fig. 6). A significant decrease in Q 10 values with latitude was observed in January (P = 0.0083), with the lowest values observed (Q 10 = 1.2) for the population from Gulfo di Oristano (20), and the highest values for the population from the Gulf of Gdansk (6). In April, this trend vanished, mainly due to the reduced Q 10 values of mussels from the northernmost sampling stations. During the following seasons, July and October, mean Q 10 values decreased further and latitudinal variation disappeared.

As a function of the acclimatization temperature, both low and high Q 10 values were found at low ambient temperatures (Fig. 7A,B). The maximum Q 10 values observed at a given temperature decreased with increasing acclimatization temperature for both taxa. To illustrate this, we fitted lines of maximum Q 10 values as a function of temperature. These lines crossed the Q 10 = 1 line at ∼23 °C for M. balthica and at ∼24 °C for Mytilus spp. (Fig. 7A,B, line a). In addition to the maximum Q 10 values for all Mytilus spp. populations, group-specific lines could be drawn (lines a–c in Fig. 7A). This resulted in different intercepts for the Q10 = 1 line: at ∼17 °C for the Baltic Sea group, at ∼19 °C for the North Sea group and at ∼24 °C for the Bay of Biscay and Mediterranean Sea group. No differentiation of the maximum thermal sensitivity of the metabolic rate was observed for M. balthica populations (Fig. 7B).

Q10 values as a function of the acclimatization temperature, presented per genetic group. The diamonds, triangles and circles represent the Baltic Sea group, the North Sea group and the Mediterranean Sea and/or Bay of Biscay group, respectively. These graphs include measurements taken from all research sites. Lines of maximum Q10 values are fitted for M. balthica (B; a) and for Mytilus spp. (A) per genetic group: a the Mediterranean Sea and Bay of Biscay group, b the North Sea group, and c the Baltic Sea group

Discussion

Rates at high experimental temperatures

When exposed to experimental temperatures of 24 or 31 °C, respiration rates in both Mytilus spp. and M. balthica may exceed 2.0 (mg O2/g (dry weight)/h). Such high rates were mostly observed in winter and spring, probably due to the low activation energy required for enzyme-catalyzed reactions at this time of the year (Hochachka and Somero 2002). The population from the Mecklenburg Bight (7) exhibited exceptionally high respiration rates for Baltic Sea mussels in the summer. In general, these high respiration rates measured at high experimental temperatures are not expected to occur in the field. When the summer starts, and peaks in habitat temperatures (24 °C+) occur in the field, the amplitude of the respiratory response at these higher temperatures declined. We propose that this modulation of metabolic thermal sensitivity is a protection mechanism that prevents excessive metabolic rates at high ambient temperatures. At the northern Baltic Sea station (3), the high thermal sensitivity of the metabolic rate did not result in high respiration rates in wintertime (which includes April in this area). Rates declined above 10 °C, indicating that the respiratory capacity was low and that acclimatization to increasing temperatures in springtime requires physiological changes in these clams.

Comparing both taxa, their respiratory responses to the experimental temperature range were rather different. The most striking difference is the regular occurrence of the breakpoint temperature between 24 and 31 °C in Mytilus spp., which was mostly absent for M. balthica (Fig. 8A,B; in these graphs we summarize all respiration rates assessed for all populations during all seasons between 2003 and 2005). This breakpoint temperature may reflect the thermal tolerance limits of marine ectotherms. It has been suggested that species with lower breakpoint temperatures are less tolerant to high temperatures (Hochachka and Somero 2002; Pörtner 2002). Interestingly, despite its apparent breakpoint temperature between 24 and 31 °C, Mytilus spp. seem to tolerate higher environmental temperatures than M. balthica, given the geographical distribution of mussels, which reaches as far south as northern Africa (Comesana et al. 1998). Nonetheless, the lethal temperatures of both taxa under submerged conditions are comparable. The LT50 values for both species were 30–31 °C in a 24-h experiment using mussels and clams that were previously acclimatized to 20–25 °C (Kennedy and Mihursky 1971; Wallis 1975).

Mean respiratory responses to temperature of Mytilus spp. (B; diamonds) and M. balthica (A; circles). Data are presented as the averages of all measurements taken (all populations and all seasons, 2003–2005). The numbers next to the labels are the number of replicate measurements taken, and the dashed lines indicate the standard deviations

Rates at acclimatization temperatures

The relations between the mean acclimatized respiration rates of the studied taxa and temperature are based on specimens from a great variety of microhabitats. Therefore, we expect these data to give a representative overview of metabolic temperature dependence in acclimatized mussels and clams. A narrow relation between temperature and acclimatized respiration rates in winter and springtime suggests that variations in the metabolic rate during this time of the year were directly dependent on temperature, and not limited by other physiological or environmental variables. A temperature-limited metabolic rate was also reflected by the high thermal sensitivity of the metabolic rate of some of the populations during those seasons. Only a few observations confirmed that the constant increase in respiration rates with acclimatization temperature can continue in summer and autumn, when most data points were found to be scattered below the upper edge slope. We suggest that the upper edge slopes represent the “metabolic scopes” of these taxa. However, since measurements are based on groups of specimens, respiration rates of single individuals can be higher.

The relatively high acclimatized respiration rates (1.0–1.5 mgO2/g/h) most probably result from metabolic up-regulation, related to elevated rates of digestion and protein synthesis. The present study did not find any acclimatized routine respiration rates that exceeded 1.5 (mg O2/g/h) in mussels or clams. In general, respiration rates exceeding 1.5 mg O2/g(dry weight)/h can be considered to be high and will rarely occur under ambient conditions. Also, in other studies no acclimatized routine respiration rates higher than 1.5 mg O2/g(dry weight)/h have been reported for M. balthica (McMahon and Wilson 1981; Wilson and Elkaim 1991; Hummel et al. 2000) or Mytilus spp. (Arifin and Bendel-Young 2001; Bayne and Widdows 1978; Tedengren et al. 1999; Thompson 1984). Towards tolerance limits, the arising breakpoint temperature will force down the “metabolic scope,” as indicated by the mussel populations from the Santa Giusta lagoon (21) and Gulfo di Oristano (20) in July, and for clams from Point d’Aiguillon (15) in July and October. Physiological rates that are acclimatized to (near) breakpoint temperatures are rarely described for ectotherms.

The relatively low respiration rates at acclimatization temperatures >12 °C are interpreted as metabolic down-regulation resulting from both intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Brokordt et al. 2000; Burkey 1971; Velasco and Navarro 2003). The extremely low respiration rate of mussels from the Bidasoa estuary (16) in January was an exception, presumably caused by a temporary drop in ambient salinity (from 34 to 9 PSU). Such hypo-osmotic conditions are known to induce a metabolic depression in Mytilus spp. (Newell 1969; Storey and Storey 1990).

In general, Baltic Sea populations exhibited relatively low respiration rates, intermediate respiration rates were found in the North Sea populations, and relatively high metabolic rates in the Bay of Biscay and Mediterranean Sea populations. These observations fall together with the low growth rates in bivalves from the Baltic Sea, intermediate growth rates in North Sea populations, and the highest growth rates found in the Bay of Biscay and in some Mediterranean Sea populations (Bachelet 1980; Fuentes et al. 1998, 2000; Gangnery et al. 2004; Hummel et al. 1998; Peteiro et al. 2006; Westerborn et al. 2002). This indicates that mean routine respiration rates, measured at ambient temperatures, do indeed reflect the metabolic rate and ultimately the physiological performance of bivalves.

Separate curves describing the respiratory response to acclimatization temperatures were found for the three genetic groups of Mytilus populations. This resulted in group-specific respiration rates at a given temperature, which was significantly lower for the Baltic Sea group that exhibited reduced metabolic rates at intermediate temperatures (12–15 °C), where populations from the other genetic groups mostly exhibited optimal respiration rates (see Fig. 5c). In line with our earlier conclusion that the observed suboptimal respiration rates represent metabolic adjustment to limiting extrinsic factors (including energy–substrate availability), we expect that these group-specific response curves mainly reflect the food conditions in the respective sea-basins during the warmer months of the year. This assumption is supported by the seasonal variation in chlorophyll concentrations The chlorophyll concentrations in the Baltic Sea decline (Heiskanen and Leppänen 1995) at thermal conditions that correspond to the maximum annual chlorophyll concentrations in the North Sea and the Bay of Biscay (Colebrook 1979) and their adjacent estuaries (Rybarczyk et al. 1993; van Bergeijk et al. 2006). It also explains the exceptionally high respiration rates of some populations from the North Sea group at high habitat temperatures, e.g., specific dynamic action, facilitated by high ambient food availability. Still, differential genetic adaptation to temperature may add to the observed physiological differences, and cannot be excluded as an explanation.

The relation between the respiration rate and the acclimatization temperature shows great overlap upon comparing Mytilus spp. with M. balthica. Further comparison with other studies demonstrates that seasonal variation in the acclimatized respiration rates obtained from two Mytilus populations from England (Bayne and Widdows 1978) fits the relation described in this study. The respiratory performances of other bivalve species, such as Cerastoderma edule (Newell and Bayne 1980), Ostrea edulis (Beiras et al. 1994), or Dreissena polymorpha (Sprung 1995), were highly comparable as well. This great similarity in respiratory performance among European bivalve species suggests that they share a comparable evolutionary relation with temperature.

Sensitivity of the metabolic rate to temperature changes

We hypothesized that the sensitivity to temperature of the metabolic rate would decrease towards more southern localities, especially in the warmer seasons. Such latitudinal clines were only observed in January for Mytilus spp., and in April for M. balthica populations. In October no specific pattern was observed for Mytilus populations, since the Q 10 values were low in all populations. This may be related to limiting food conditions in autumn. Absence of significant latitudinal clines in July was caused by cline-interruption, which corresponded to the geographic transition of one genetic group to the next. These genetic group specific clines became especially apparent in mussels when the Q 10 was presented as a function of the acclimatization temperature (Fig. 6).

The obtained Q 10 values decreased with increasing acclimatization temperature for three reasons. First, metabolic down-regulation for energetic balancing results in a reduced Q 10. Second, Q 10 will decrease near breakpoint temperatures. Third, during thermal fluctuations that involve high peaks in habitat temperature, ectotherms will minimize the sensitivity of their metabolic rate, avoiding excessive rates when exposed to elevated temperatures (Peck et al. 2002; Widdows 1976; Wilson and Elkaim 1991). Thus, the increasing abundance of relatively nutrient-poor and thermally dynamic habitats causes a gradual shrinking of the ecological niche of these bivalve taxa towards the warm end of their distribution range. The group-specific clines discussed in the preceding paragraph indicated differential adaptation to temperature among Mytilus spp. populations. Since these bivalve species have great dispersal capacities, strongly coupled to hydrodynamic circulation (Gilg and Hilbish 2002), genetic divergence within these species requires geographic isolation. During isolation in different climatic regions, selective genetic variation may have evolved at the same spatial scale as the observed neutral genetic variation. This may explain why the biogeography of these genetic groups is associated with European temperature gradients. Physiological studies revealed that mussels from different genetic groups exhibit different growth rates when hatched under similar conditions (Beaumont et al. 2004; Hillbish et al. 1994). Differential thermal adaptation has recently been demonstrated for different mussel species from the West coast of North America as well (Fields et al. 2006). The differential adaptation to temperature indicated by our results, combined with the strong spatial variability of the coastal climate in the Bay of Biscay (Puillat et al. 2004), may explain the broad and mosaic-like transition from one mussel-group present in this area to the next (Bierne et al. 2003).

Q10 values lower than one only occur beyond the breakpoint temperature, where the metabolic rate decreases with increasing temperature. Since thermal conditions beyond breakpoint temperatures are not beneficial for bivalve performance and are most probably lethal when extended, it is most interesting to observe that the southernmost Mytilus spp. populations in our research area exhibited Q10 values of less than one at acclimatization temperatures in July 2004. In the Santa Giusta Lagoon (21), the monthly mean water temperature reached 27 °C, exceeding the breakpoint temperature of mussels. Very few bivalves survived the summer of 2004 in the Santa Giusta lagoon (21), indicating that thermal tolerance limits were indeed crossed under field conditions. Survival of temperature-induced stress depends on its duration and on the physiological status and condition of the organisms. Widdows and Bayne (1971) found that mussels can cope with relatively high temperatures so long as they can regularly recover in water at a suitably low temperature. This is an important strategy that allows survival of temporary heat exposure, e.g., when exposed to the air during low tide in summer. The range and limits of this relation for mussels or clams have not been studied in depth yet.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the respiratory responses to temperature of two European bivalve taxa are greatly dependent on seasonal variations in temperature. These responses, obtained throughout all seasons and at a large geographic scale, fit together in a framework when presented as a function of the acclimatization temperature. This framework is useful in both the fundamental and the applied sciences, facilitating the interpretation of respiration rates measured under ambient conditions, and the further development of ecophysiological theory. We observed that the maximum thermal sensitivity of the metabolic rate decreases with increasing acclimatization temperature, crossing a threshold (Q 10 = 1) in Mytilus spp. at the maximum acclimatization temperatures observed in the field. Whether the temperature quotient will become less than one in M. balthica populations when the acclimatization temperature exceeds 23 °C cannot be answered with any certainty, since no breakpoint temperature is observed in the experimental southern populations under or near ambient conditions.

(Onto)genetic adaptation to regionally different climates implies that climate change will affect not only marginal populations via their metabolic rates, but all genetic groups are expected to shift northward with increasing temperatures. Although the dispersal capacity of mussel larvae and the active transport of juvenile and adult mussels for aquaculture purposes support range shifts with the speed of climate change, other ecological and physiological variables and their impact on the environment need to be investigated to predict the fate of mussels and other bivalve populations under changing climatic conditions. For M. balthica populations, no differential adaptation to temperature was observed among divergent groups, which leads us to expect that the direct impact of climate-induced temperature changes will be restricted to the southernmost populations.

References

Arifin Z, Bendell-Young LI (2001) Cost of selective feeding by the blue mussel (Mytilus trossulus) as measured by respiration and ammonia excretion rates. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 260:259–269

Bachelet G (1980) Growth and recruitment of the tellinid bivalve Macoma balthica at the southern limit of its geographical distribution, the Gironde estuary (SW France). Mar Biol 59:105–117

Bayne BL, Widdows J (1978) The physiological ecology of two populations of Mytilus edulis L. Oecologia 37:137–162

Beaumont AR, Turner G, Wood AR, Skibinski DOF (2004) Hybridisations between Mytilus edulis and Mytilus galloprovincialis and performance of pure species and hybrid veliger larvae at different temperatures. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 302:177–188

Beiras R, Camacho APr, Albentosa M (1994) Comparison of the scope for growth with the growth performance of Ostrea edulis seed reared at different food concentrations in an open-flow system. Mar Biol 119:227–233

Bierne N, Borsa P, Daguin C, Jollivet D, Viard F, Bonhomme F, David P (2003) Introgression patterns in the mosaic hybrid zone between Mytilus edulis and M. galloprovincialis. Mol Ecol 12:447–461

Blackburn TM, Lawton JH, Perry JN (1992) A method of estimating the slope of upper bounds of plots of body size and abundance in natural animal assemblages. Oikos 65:107–112

Brokordt KB, Himmelman JH, Guderley HE (2000) Effect of reproduction on escape responses and muscle metabolic capacities in the scallop Chlamys islandica Muller 1776. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 251:205–225

Buchanan JA, Stewart BA, Davies BR (1988) Thermal acclimation and tolerance to lethal high temperature in the mountain stream amphipod Paramelita nigroculus (Barnard). Comp Biochem Physiol A 89:425–431

Burky AJ (1971) Biomass turnover, respiration, and interpopulation variation in the stream limpet Ferrissia rivularis (Say). Ecol Monogr 41:235–251

Cade BS, Terrell JW, Schroeder RL (1999) Estimating effects of limiting factors with regression quantiles. Ecology 80:311–323

Clarke A (1991) What is cold adaptation and how should we measure it? Am Zool 31:81–92

Colebrook JM (1979) Continuous plankton records: seasonal cycles of phytoplankton and copepods in the North Atlantic ocean and the North Sea. Mar Biol 51:23–32

Comesana AS, Posada D, Sanjuan A (1998) Mytilus galloprovincialis Lmk. in northern Africa. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 223:271–283

Daguin C, Bonhomme F, Borsa P (2001) The zone of sympatry and hybridization of Mytilus edulis and M. galloprovincialis, as described by intron length polymorphism at locus mac-1. Heredity 86:342–354

Feder ME, Hofmann GE (1999) Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Ann Rev Physiol 61:243–282

Fields PA, Rudomin EL, Somero GN (2006) Temperature sensitivities of cytosolic malate dehydrogenases from native and invasive species of marine mussels (genus Mytilus): sequence-function linkages and correlations with biogeographic distribution. J Exp Biol 209:656–667

Fuentes J, Gregorio V, Giraldez R, Molares J (2000) Within-raft variability of the growth rate of mussels, Mytilus galloprovincialis, cultivated in the Ria de Arousa (NW Spain). Aquaculture 189:39–52

Fuentes J, Molares J, Villalba A (1998) Growth, mortality and parasitization of mussels cultivated in the Ria de Arousa (NW Spain) from two sources of seed: intertidal rocky shore vs. collector ropes. Aquaculture 162:231–240

Gangnery A, Bacher C, Buestel D (2004) Application of a population dynamics model to the Mediterranean mussel, Mytilus galloprovincialis, reared in Thau Lagoon (France). Aquaculture 229:289–313

Geller JB (1999) Decline of a native mussel masked by sibling species invasion. Conserv Biol 13:661–664

Gilg MR, Hilbish TJ (2002) The geography of marine larval dispersal: coupling genetics with fine-scale physical oceanography. Ecology 84:2989–2998

Heiskanen AS, Leppänen JM (1995) Estimation of export production in the coastal Baltic Sea: effect of resuspension and microbial decomposition on sedimentation measurements. Hydrobiologia 316:211–224

Hilbish TJ, Bayne BL, Day A (1994) Genetics of physiological differentation within the marine mussel genus Mytilus. Evolution 48:267–286

Hochachka PW, Somero GN (2002) Biochemical adaptation. Mechanism and process in physiological evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 466

Hofmann GE, Somero GN (1996) Interspecific variation in thermal denaturation of proteins in the congeneric mussels Mytilus trossulus and M. galloprovincialis: evidence from the heat-shock response and protein ubiquitination. Mar Biol 126:65–75

Hummel H (2006) The impact of biodiversity changes in coastal marine benthic ecosystems (final report; EVK3-2001-00146). Netherlands Institute of Ecology, Yerseke, pp 203

Hummel H, Bogaards R, Bek T, Polishchuk L, Sokolov K, Amiard-Triquet C, Bachelet G, Desprez M, Naumov A, Strelkov P (1998) Growth in the bivalve Macoma balthica from its northern to its southern distribution limit: a discontinuity in North Europe because of genetic adaptations in Arctic populations? Comp Biochem Physiol A 120:133–141

Hummel H, Bogaards RH, Bachelet G, Caron F, Sola JC, Amiard-Triquet C (2000) The respiratory performance and survival of the bivalve Macoma balthica (L.) at the southern limit of its distribution area: a translocation experiment. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 251:85–102

Kennedy VS, Mihursky JA (1971) Upper temperature tolerances of some estuarine bivalves. Chesapeake Sci 12:193–204

Luttikhuizen PC, Drent J, Baker AJ (2003) Disjunct distribution of highly diverged mitochondrial lineage clade and population subdivision in a marine bivalve with pelagic larval dispersal. Mol Ecol 12:2215–2229

Luttikhuizen PC, Koolhaas A, Bol A, Piersma T (2002) Mytilus galloprovincialis-type foot-protein-1 alleles occur at low frequency among mussels in the Dutch Wadden Sea. J Sea Res 48:241–245

Lyons C, Dowling V, Tedengren M, Gardestrom J, Hartl MGJ, O’Brien N, van Pelt FNAM, O’Halloran J, Sheehan D (2003) Variability of heat shock proteins and glutathione S-transferase in gill and digestive gland of blue mussel, Mytilus edulis. Mar Environ Res 56:585–597

McMahon RF, Russell-Hunter WD, Aldridge DW (1995) Lack of metabolic temperature compensation in the intertidal gastropods, Littorina saxatilis (Olivi) and L. obtusata (L.). Hydrobiologia 309:89–100

McMahon RF, Wilson JG (1981) Seasonal respiratory responses to temperature and hypoxia in relation to burrowing depth in three intertidal bivalves. J Therm Biol 6:267–277

McMahon RF (1973) Respiratory variation and acclimation in the freshwater limpet, Laevapex fuscus. Biol Bull 145:492–508

NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2005) Physical Oceanography Distributed Active Archive Center website. http://podaac-www.jpl.nasa.gov/index.html. Cited 6 July 2007

Newell RC (1969) Effect of fluctuations in temperature on the metabolism of intertidal invertebrates. Am Zool 9:293–307

Newell RC, Bayne BL (1980) Seasonal changes in the physiology, reproductive condition and carbohydrate content of the cockle Cardium (=Cerastoderma) edule (Bivalvia: Cardiidae). Mar Biol 56:11–19

Peck LS, Portner HO, Hardewig I (2002) Metabolic demand, oxygen supply, and critical temperatures in the Antarctic bivalve Laternula elliptica. Physiol Biochem Zool 75:123–133

Peteiro LG, Babarro JMF, Labarta U, Fernandez-Reiriz MJ (2006) Growth of Mytilus galloprovincialis after the Prestige oil spill. ICES J Mar Sci 63:1005–1013

Pörtner HO (2001) Climate change and temperature-dependent biogeography: oxygen limitation of thermal tolerance in animals. Naturwissenschaften 88:137–146

Pörtner HO (2002) Climate variations and the physiological basis of temperature dependent biogeography: systemic to molecular hierarchy of thermal tolerance in animals. Comp Biochem Physiol A 132:739–761

Puillat I, Lazure P, Jegou AM, Lampert L, Miller PI (2004) Hydrographical variability on the French continental shelf in the Bay of Biscay, during the 1990s. Cont Shelf Res 24:1143–1163

Raven JA, Geider RJ (1988) Temperature and algal growth. New Phytol 110:441–461

Rybarczyk H, Desprez M, Ducrotoy JP, Olivesi R, Delesmont R, Jamet F, Elkaim B (1993) Dynamics of nutrients and faecal bacteria in a macrotidal estuary, the Bay of Somme (France). Mar Biol 27:395–404

Skibinski DOF (1985) Mitochondrial DNA variation in Mytilus edulis L. And the padstow mussel. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 92:251–258

Somero GN (2002) Thermal physiology and vertical zonation of intertidal animals: optima, limits, and costs of living. Integr Comp Biol 42:780–789

Sprung M (1995) Physiological energetics of the zebra mussel Dreissena polymorpha in lakes. III. Metabolism and net growth efficiency. Hydrobiologia 304:147–158

Storey KB, Storey JM (1990) Metabolic rate depression and biochemical adaptation in anaerobiosis, hibernation and estivation. Q Rev Biol 65:145–174

Tedengren M, Olsson B, Bradley B, Zhou L (1999) Heavy metal uptake, physiological response and survival of the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) from marine and brackish waters in relation to the induction of heat-shock protein 70. Hydrobiologia 393:261–269

Thomson JD, Weiblen G, Thomson BA, Alfaro S, Legendre P (1996) Untangling multiple factors in spatial distributions: lilies, gophers, and rocks. Ecology 77:1698–1715

Thompson RJ (1984) The reproductive cycle and physiological ecology of the mussel Mytilus edulis in a subarctic, non-estuarine environment. Mar Biol 79:277–288

van Bergeijk SA, Wollenzien U, Schönefeldt K, Stal LJ (2006) Seasonal variation in dimethylsulfoniopropionate related to microphytobenthos composition in intertidal estuarine sediments. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 320:55–63

Varvio S-L, Koehn RK, Vainola R (1988) Evolutionary genetics of the Mytilus edulis complex in the North Atlantic region. Mar Biol 98:51–60

Velasco LA, Navarro JM (2003) Energetic balance of infaunal (Mulinia edulis King, 1831) and epifaunal (Mytilus chilensis Hupe, 1854) bivalves in response to wide variations in concentration and quality of seston. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 296:79–92

Wallis RL (1975) Thermal tolerance of Mytilus edulis of Eastern Australia. Mar Biol 30:183–191

Westerbom W, Kilpi M, Mustonen O (2002) Blue mussels, Mytilus edulis, at the edge of the range: population structure, growth and biomass along a salinity gradient in the north-eastern Baltic Sea. Mar Biol 140:991–999

Widdows J (1976) Physiological adaptation of Mytilus edulis to cyclic temperatures. J Comp Physiol B 105:115–128

Widdows J, Bayne BL (1971) Temperature acclimation of Mytilus edulis with reference to its energy budget. J Mar Biol Assoc 51:827–843

Wilson JG, Elkaim B (1991) Tolerances to high temperature of infaunal bivalves and the effect of geographical distribution, position on the shore and season. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 71:169–177

Wilson JG, Davis JP (1984) The effect of environmental variables on the oxygen consumption of the protobranch bivalve Nucula turgida (Leckenby and Marshall). J Molluscan Stud 50:73–77

Wonham MJ (2004) Mini-review: distribution of the mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis (Bivalvia: Mytilidae) and hybrids in the northeastern Pacific. J Shellfish Res 23:535–543

Acknowledgements

This research, NIOO publication No. 4109, was supported by the European Committee (Research Directorate General, Environmental Program Marine Ecosystems) through the BIOCOMBE-project (contract EVK3-2001-00146). We wish to thank all colleagues that assisted during fieldwork, and all marine institutions for their hospitality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Martin Attrill.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jansen, J.M., Pronker, A.E., Kube, S. et al. Geographic and seasonal patterns and limits on the adaptive response to temperature of European Mytilus spp. and Macoma balthica populations. Oecologia 154, 23–34 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0808-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0808-x