Abstract

Novel methodologies for detection of chromosomal abnormalities have been made available in the recent years but their clinical utility in prenatal settings is still unknown. We have conducted a comparative study of currently available methodologies for detection of chromosomal abnormalities after invasive prenatal sampling. A multicentric collection of a 1-year series of fetal samples with indication for prenatal invasive sampling was simultaneously evaluated using three screening methodologies: (1) karyotype and quantitative fluorescent polymerase chain reaction (QF-PCR), (2) two panels of multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), and (3) chromosomal microarray-based analysis (CMA) with a targeted BAC microarray. A total of 900 pregnant women provided informed consent to participate (94% acceptance rate). Technical performance was excellent for karyotype, QF-PCR, and CMA (~1% failure rate), but relatively poor for MLPA (10% failure). Mean turn-around time (TAT) was 7 days for CMA or MLPA, 25 for karyotype, and two for QF-PCR, with similar combined costs for the different approaches. A total of 57 clinically significant chromosomal aberrations were found (6.3%), with CMA yielding the highest detection rate (32% above other methods). The identification of variants of uncertain clinical significance by CMA (17, 1.9%) tripled that of karyotype and MLPA, but most alterations could be classified as likely benign after proving they all were inherited. High acceptability, significantly higher detection rate and lower TAT, could justify the higher cost of CMA and favor targeted CMA as the best method for detection of chromosomal abnormalities in at-risk pregnancies after invasive prenatal sampling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During pregnancy management, indications for invasive prenatal chromosome analysis are usually established balancing the a priori risk of detectable chromosomal aberrations in the fetus and the risk of miscarriage associated with invasive fetal sampling (Tabor et al. 1986; MRC working party on the evaluation of chorion villus sampling 1991). Screening tests, which take into account maternal age (Cuckle et al. 1987), maternal serum biochemical parameters (Wald et al. 1988; Macri et al. 1991), and fetal ultrasound markers (Benacerraf et al. 1987), are used to provide a risk assessment for Down syndrome, neural tube defects, and many fetal malformations, but are not useful biomarkers for other medical conditions. At present, various screening strategies and diagnostic methods are implemented in different countries.

G-banding karyotype analysis became the gold standard for detection of fetal chromosomal abnormalities in the 1970s (Steele and Breg 1966; Caspersson et al. 1970). Nevertheless, a number of chromosomal defects associated with moderate to severe clinical conditions, including genomic disorders and subtelomeric rearrangements (Flint et al. 1995), fall below the resolution limit of the karyotype (<5–10 Mb). In addition, karyotyping requires living cells, which increases turn-around time (TAT), risk of culture artifacts, and might prevent the analysis in situations where cell viability is compromised (i.e. products of conception).

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) on interphase nuclei, quantitative fluorescent PCR (QF-PCR) (Mansfield 1993; Pertl et al. 1994), and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) (Schouten et al. 2002) have emerged as rapid (less than 3 days) alternatives for detection of a discrete number of chromosomal aneuploidies or submicroscopic rearrangements. Experimental and clinical data gathered for years has prompted the routine adoption of QF-PCR or FISH (Blennow et al. 1994) together with conventional banding cytogenetics as the standard of care for prenatal detection of chromosomal abnormalities in at-risk pregnancies in many countries (Shaffer and Bui 2007).

Chromosome microarray analysis (CMA) combines short TAT and high resolution with massive analysis of copy number variation throughout the genome. In contrast, it cannot identify balanced rearrangements, is still relatively expensive, and may detect a number of variants of uncertain clinical significance (VOUS). While SNP-based microarrays are able to detect polyploidies and uniparental disomies, purely CGH-based platforms (like the BAC-based used in this study) are not capable of identifying such events.

Extensive experience has already been acquired with the use of MLPA and CMA in postnatal diagnosis of multiple conditions. Recently, a consensus document has been published on the clinical suitability of CMA as the first-tier method for the study of cases of intellectual disability or congenital malformations (Miller et al. 2010). An economic evaluation also demonstrated that in postnatal analysis, the preferential use of CMA instead of karyotype is cost effective (Regier et al. 2010). It is also relevant the high detection rate of genomic imbalances in neonates with birth defects shown by CMA (Lu et al. 2008). Although several studies have been published to date suggesting higher detection rates (Sahoo et al. 2006; Van den Veyver et al. 2009; Maya et al. 2010), prenatal CMA experience is still limited and no prospective studies have been addressed to demonstrate the clinical utility of this novel technology in prenatal settings.

We present here the results of a multicentric comparative study of clinical utility (i.e. likelihood that a test will lead to an improved health outcome) and costs of chromosomal aberration detection methods in invasive prenatal diagnosis of 900 consecutive pregnant women with indication for fetal sampling.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

The entire study received Institutional Review Board approval from the Ethics Committees for Clinical Research of both participating institutions. A consecutive series of pregnant women referred to the obstetrics departments of the Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid) and Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona), both public hospitals of the Spanish health system, between February 2009 and March 2010 for prenatal invasive fetal sampling were offered to participate in the study after a pre-test session of genetic counseling. In this session, we explained their risk for fetal anomalies and the methods of sampling and analyses. We discussed with couples the benefits, limitations and timing for result delivery in routine analysis (karyotype and QF-PCR), as well as the possibility to extend prenatal studies with additional analysis (MLPA and CMA) with the a priori benefits, limitations and timing of those studies. The possibility to detect a higher number of genomic alterations of unknown significance was also discussed. During the first 6 months of the study, 402 pregnant women were also invited to answer a short questionnaire on socio-demographic characteristics, subjective anxiety levels, and the reasons to accept or refuse prenatal diagnostic tests with novel technologies.

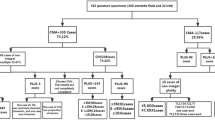

A total of 900 women who provided informed consent entered the study, and 906 fetal samples were obtained (6 twin gestations). Main indications for sampling were abnormal ultrasound findings, altered biochemical screening, familial history of chromosomopathy or other genetic condition, advanced maternal age (>37 years old) and other exceptional conditions (high-risk twin pregnancy, suspected viral infection, among others) (Table 1). Fetal samples referred for maternal anxiety were also included in the study, although this is not an indication of recognized high risk of chromosomopathy.

A post-test genetic counseling session was provided in all cases when a genetic alteration was detected by any method. The most important topic of this session was the clinical relevance and prognosis of the detected alteration, considering the possibility of incomplete penetrance and/or variable expressivity, along with the appropriateness of further genetic analysis in the parents to determine if the alteration was inherited or de novo.

The nature of the collected fetal sample mostly depended on the gestational age at the indication for sampling. Chorionic villus samples (CVS) were obtained from gestations in the range of eight to 14 weeks (n = 164, 18.0%), amniotic fluid (AF) through amniocentesis from weeks 15 to 21 (n = 728, 80.0%), and fetal blood (FB) by funiculocentesis at 20–22 weeks (n = 14, 2.0%). In order to warrant the optimal performance of the standard clinical testing, a minimum sample size was allocated for QF-PCR and karyotyping (0.5 mg of CVS, 12 mL of AF and 300 μL of FB), while the remaining was used for DNA isolation (at least 0.5 mg for CVS, 4 mL for AF, or 300 μL for FB, based on previous data). Therefore, only samples with more than 1 mg of CVS, 16 mL of AF and 600 μL of FB, were processed in the study.

Statistics

Exact binomial confidence limits were calculated to test sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value as previously described (Collet 1999). We also computed the diagnostic accuracy, defined as the proportion of all tests that give a correct result. Finally, Youden’s index was computed as the difference between the true positive rate and the false positive rate. Youden’s index ranges from −1 to +1 with values closer to one if both sensitivity and specificity are high (Altman et al. 2000).

Calculation of costs

We calculated the cost per test and the cost per diagnosis associated with each technology based exclusively on direct costs including consumables (reagents) and personnel costs in Spain (2010 prices). We estimated hands-on-time per laboratory technician for performing assays, and genetics specialist for data analysis and interpretation, and assumed an average of 20 samples analyzed per week. The cost per diagnosis was calculated on the basis of the costs and diagnostic outcomes (number of diagnoses) of the 906 samples analyzed in our study. We also attempted to estimate a rough incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The ICER is given by the ratio of the difference in costs between technologies (incremental costs) and the difference in effects or outcomes (incremental effects); this ratio represents the additional cost per extra unit of effect/outcome of one technology in comparison with another (Drummond et al. 2005). In this study we estimated a rough ICER of CMA in comparison with karyotype, considering the number of diagnoses as a measure of effects, although we are aware that this is an intermediate outcome.

Results

Acceptance of novel prenatal testing procedures

All women who answered the questionnaire after the pre-test counseling session (402/402) considered to have received enough information of the ongoing study in order to make a decision about participation. Among the 94% who decided to participate, the main motivations were to obtain more information (45%), to contribute to scientific progress (48%), to decrease anxiety (5%), and in gratitude for the professional kindness (1%). Fifty-six women (6%) declined to join the study but continued with standard prenatal testing; 60% of them argued more anxiety due to extra testing. The median level of perceived anxiety prior to testing was three on a scale between one (very low) and five (very high), mostly due to the reason for referral for prenatal testing. The fact of entering the study did not represent any additional source of stress in those who accepted participating.

Technical performance and turn-around-time

Good quality DNA for the different analyses was obtained from 95% of CVS, 100% from FB, and 56% from AF uncultured samples; thus it was necessary to obtain DNA from cultured chorionic villi and amniotic fluid in 5% and in 44% of the cases, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). One advantage of performing multiple techniques on the same sample was that failures could be attributed to either a single technology or the common manipulation in most cases. We considered a technical failure when it was not possible to provide a definitive result with that technology for any reason. Karyotype was the most robust technique with only eight failures (0.9%), all cases due to cell culture failure. CMA showed a failure rate of 1.1% (10/906), the same as QF-PCR, but seven out of the ten failing samples had been extracted the same day. MLPA was the less robust technique, with a failure rate of 10.1% (183/1812), 61 with the subtelomeric set of probes and 122 to the genomic disorders (RGD) set (see Supplementary Methods). In most cases, MLPA failure was attributable to uncertainty in the interpretation of noisy electropherograms with variable peak heights.

TAT was measured since the arrival of the biological sample to the laboratory and until the results of the main test were obtained. Time for downstream analysis of the findings (parental testing, validation by an alternative genetic test, etc.) was not computed to determine the TAT mainly because additional samples were not readily available (parental samples were not collected on a regular basis), and because the approaches required for validations were different for each case and technology. Overall, QF-PCR was the fastest technique generating results with an average TAT of two working days, while the average TAT for CMA and MLPA from uncultured specimens was 7 days. For cultured samples, including G-banding karyotype, average TAT ranged between 4 and 27 days (Supplementary Table 1).

Chromosomal aberrations detected

A total of 100 chromosomal aberrations were identified in 95 different samples and were classified into different categories according to their predicted clinical significance (Tables 2, 3, and Supplementary Table 2 for detailed description). In the Pathologic category we detected 26 trisomies, 3 triploidies, 3 derivative/marker chromosomes, 6 segmental aneuploidies and 2 fully penetrant microdeletion disorders. Seventeen fetuses were observed to carry a clinically relevant alteration, including 11 sex chromosome aneuploidies and six recurrent microduplication syndromes. Twenty-one aberrations corresponded to the Uncertain Relevance category, four cytogenetically balanced rearrangements and 16 copy number alterations, three of them in malformed fetuses. The Benign category was composed of 22 variants. Although cross-validation was provided by the simultaneous use of multiple technologies in most cases, we used additional molecular techniques in the follow-up of some of the alterations identified by CMA, including the analysis of parental samples to define whether the rearrangements were de novo or inherited (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). As an example, FISH was used for confirmation of the carrier status for a balanced rearrangement in the mother of a fetus with an unbalanced alteration (Supplementary Figure 1).

Sensitivity, specificity and detection rates

The nature and resolution of the assessed technologies necessarily impact on the final detection rate achieved by each of them, with intrinsic a priori limitations. In order to perform a comparative evaluation of the different methods by means of specificity and sensitivity, we used all chromosomal abnormalities identified with predictable clinical outcome, regardless of its size, as the one-for-all measure unit. Specificity was found to be very high in all cases, above 99% for QF-PCR, karyotype, and CMA, and 97% for MLPA. However, sensitivity was significantly higher for CMA (98.2%) than for other technologies (Table 4). Youden’s index also revealed that CMA combines the highest true to false positive ratio.

The overall detection rate of pathological and clinically relevant alterations was 6.3% (57/906 samples) with different detection capabilities depending on the technology (Table 1). CMA yielded a superior detection rate in fetuses with abnormal ultrasound (13.3%), but it was also significant in pregnancies with a priori low risk (1.7 and 4.0%, anxiety and advanced maternal age with normal screening, respectively) (Table 1), far above the risk of pregnancy loss by invasive sampling (Driscoll and Gross 2009). Overall, CMA detected 32% more alterations than QF-PCR and karyotype, including eight conditions with rather poor prognosis for postnatal development (Table 3). This percent increase in detection rates was equally high among low-risk pregnancies and on those with an ultrasound anomaly (Supplementary Table 3).

Another advantage of CMA was the ability to better characterize two supernumerary markers (sSMC) and a derivative chromosome identified by karyotyping (Table 3).

Interpretation and reporting criteria

Interpretation of results in studies using targeted CMA is conceptually more straightforward than in studies using whole-genome microarrays, although no increase of unclear results has been reported in previous comparative studies (Coppinger et al. 2009). Although a great effort was made to avoid using probes coinciding with polymorphic copy number variants (CNVs), this was not possible for two main reasons. First, when the array was designed, the knowledge of the genome distribution of CNVs was limited; and second, in order to interrogate some specific syndromes it was necessary to use probes located in variable regions.

Alterations coinciding with known polymorphic CNV regions were interpreted as benign and not included in the analysis report. Alterations identified in a region involved in a known microdeletion/microduplication syndrome were reported as pathogenic. Variants not falling into these two categories were classified as VOUS.

The identification of VOUS in prenatal testing is challenging and disturbing, since a clinical and prognostic interpretation is required. As a general rule, a genomic or cytogenetic variant is considered benign when it is inherited from a disease-free parent. However, there is always a risk in inherited variants due to incomplete penetrance or different parent-of-origin effects, while de novo events may also be benign. Two VOUS were detected by MLPA (0.2%), 3 by kayotyping (0.3%), none by QF-PCR, and 17 by CMA (1.9%), 3 of these in fetuses with ecographic malformations. All of those detected by karyotype or MLPA, and six out of seven detected by CMA and afterwards validated, were inherited from normal parents and thus considered presumably benign. The remaining 11 parents were informed and declined to undergo further genetic testing as this would have not had any impact on modifying the VOUS condition of the findings.

Costs

The cost per test ranged between €37 (QF-PCR) and €242 (CMA). QF-PCR was the less costly technology but it was also the technology that yielded less number of diagnoses. On the contrary, CMA yielded the highest number of diagnoses but being also the most expensive (Supplementary Table 4). As a result, the cost per diagnosis ranged between €991 (QF-PCR) and €3,916 (CMA). In our study, the only technology that became dominated was the combination of karyotype and QF-PCR (the current standard in several EU countries, including Spain), that is, the combination was more costly than and as effective as karyotype alone. A rough estimation showed an ICER of €6,442 per additional diagnosis with CMA in comparison with karyotype, and €4,034 if we compared CMA with karyotype plus QF-PCR.

Discussion

We have observed a very high acceptability of novel techniques for prenatal diagnosis after appropriate genetic counseling, with only 6% of women declining to enter the study due to increased anxiety. Technical performance was excellent for CMA, and similar to QF-PCR or karyotype under standard procedures. However, despite our extensive experience with the technology, MLPA showed a high rate of technical failure in uncultured AF samples, likely due to the low purity of the DNA obtained (salt and/or protein contamination). Finally, CMA revealed to be the most sensitive technique for diagnosing chromosomal alterations associated with medical conditions, being able to detect all but one clinically relevant alterations (56/57), followed by G-banding karyotype (42/57), MLPA (39/57) and QF-PCR (34/57, all detected by karyotype as well). In other words, CMA increased ~32% the detection rate of any other method. Conversely, the only clinically relevant alteration missed by CMA was a triploidy with karyotype 69, XXX, associated with a usually lethal condition in utero. This limitation could be overcome using microarrays that also interrogate nucleotide variation (SNPs), that can also detect uniparental disomies, but their clinical utility in prenatal setting remains to be proven. There was also a qualitative advantage of CMA, as the origin of small supernumerary marker chromosomes and derivatives was readily determined. Maybe the most relevant implication of our data is that 14 relevant fetal conditions (~1.6% of the entire study) would have remained undiagnosed using only the currently implemented detection methods in the clinic. The use of CMA resulted in an increased detection rate regardless of the indication for study. This becomes especially evident in the high-risk group (ultrasound findings), in which the percentage of detection was elevated to 13.3%; but also in groups with a priori low risk, which showed a detection rate far above 1/100 and a relative increase over 45% when compared to currently implemented methods (Supplementary Table 3).

Since a decision on the continuation of a pregnancy might follow the diagnostic findings of a prenatal test, it is not desirable to identify VOUS and there are some difficulties dealing with some clinically relevant conditions with variable expressivity or incomplete penetrance. We tried to minimize VOUS by designing a targeted microarray, that interrogates only regions of known clinical relevance and using large segments of DNA as probes, and MLPA panels were also selected with similar criteria. Overall, CMA detected 17 of the total 21 VOUS identified, although 3 of them might be causative as they were found in fetuses with malformations. Most VOUS could be classified as likely benign after proving they all were inherited from a parent with no-disease phenotype. For the management of such findings, it is of extraordinary help the development of public and trustable databases of variation on normal individuals, such as the database of genome variants (DGV) and the initiatives to catalogue normal and pathological variation from the ISCA and DECIPHER consortia. The minimization of VOUS is just a matter of time and of better describing structural variation in larger cohorts of cases and controls by means of different -omic approaches, which would allow establishing a solid statistical framework for assigning (or not) pathogenicity to each specific copy number variant. In such a future scenario, the use of higher genome coverage approaches might be preferred.

Interestingly, we detected six cases of recurrent microduplication syndromes (0.7% of our series), three inherited from a phenotypically normal parent and three de novo. We faced the difficult counseling of these genomic imbalances associated with variable phenotypes and incomplete penetrance with still scarce literature, although preliminary guidelines for clinical evaluation and anticipatory guidance have been published (Berg et al. 2010). Following a 20-week normal ultrasound evaluation, the parental decision in all cases was continuation of the pregnancy. The situation, however, is comparable to the counseling of sex chromosome aneuploidies, where the phenotype can be very mild with incompletely penetrant features.

In order to provide further objective assessment tools, we also estimated the costs of the different technologies. Although CMA is still the most expensive technology, it is also the one that yields a higher number of diagnoses. Our cost analysis study had some limitations related to the non-inclusion of some relevant costs like equipment depreciation and maintenance, as well as costs of downstream analyses required for confirming findings. Our rough estimation indicates that expenses not included in our cost analysis (mainly capital expenses to set up a clinical laboratory and direct maintenance costs) are similar for the different platforms. Thus, the most important direct costs were included and the figures reported herein can show the relative differences between technologies. The other limitation was the use of number of diagnoses as outcome measure instead of a health-related outcome (Grosse et al. 2008). Therefore, the estimated ICER is a tentative figure reported here with the aim of promoting the debate about the willingness to pay for new technologies and to show the need of economic evaluations in the field of genetic screening and diagnosis (Carlson et al. 2005). A full economic evaluation will be addressed in the future.

In summary, our data indicate that from the perspective of diagnostic capacity, sensitivity, and specificity, CMA is the most reliable technology. According to women’s acceptance, the diagnostic yield increase that CMA brings into prenatal genetic testing of risk pregnancies, the extraordinary medical and social cost of birth defects associated to chromosomal disorders, and until non-invasive methods are able to provide a similar sensitivity, we consider that CMA should already be a first-tier option for invasive prenatal diagnosis of at-risk pregnancies instead of the current combination of RAD (QF-PCR or FISH) and karyotype.

Although non-invasive assays for fetal diagnosis are an intense field of research, at present these are only experimental approaches available for specific chromosomal or single gene disorders (Chiu et al. 2011). Thus, nowadays, invasive fetal sampling is still the common practice, indicated in those cases where the risk of a detectable abnormality in the fetus is above the risk of a procedure-related pregnancy loss, ~1/200 (Driscoll and Gross 2009). While the evaluation of larger series is granted, the much higher detection rate of CMA, even in a priori low-risk groups (>1/100), should open the door to consider even deeper changes in currently established screening policies in prenatal care.

References

Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, Gardner MJ (eds) (2000) Statistics with confidence, 2nd edn. British Medical Journal Books, London, pp 28–29

Benacerraf BR, Gelman R, Frigoletto FD Jr (1987) Sonographic identification of second-trimester fetuses with Down’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 317(22):1371–1376

Berg JS, Potocki L, Bacino CA (2010) Common recurrent microduplication syndromes: diagnosis and management in clinical practice. Am J Med Genet A 152A(5):1066–1078

Blennow E, Bui TH, Kristoffersson U, Vujic M, Anneren G, Holmberg E, Nordenskjold M (1994) Swedish survey on extra structurally abnormal chromosomes in 39 105 consecutive prenatal diagnoses: prevalence and characterization by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Prenat Diagn 14(11):1019–1028

Carlson JJ, Henrikson NB, Veenstra DL, Ramsey SD (2005) Economic analyses of human genetics services: a systematic review. Genet Med 7(8):519–523 00125817-200510000-00001[pii]

Caspersson T, Zech L, Johansson C, Modest EJ (1970) Identification of human chromosomes by DNA-binding fluorescent agents. Chromosoma 30(2):215–227

Chiu RW, Akolekar R, Zheng YW, Leung TY, Sun H, Chan KC, Lun FM, Go AT, Lau ET, To WW, Leung WC, Tang RY, Au-Yeung SK, Lam H, Kung YY, Zhang X, van Vugt JM, Minekawa R, Tang MH, Wang J, Oudejans CB, Lau TK, Nicolaides KH, Lo YM (2011) Non-invasive prenatal assessment of trisomy 21 by multiplexed maternal plasma DNA sequencing: large scale validity study. BMJ (Clin Res ed) 342:c7401. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7401

Collet D (1999) Modelling binary data. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Ratón

Coppinger J, Alliman S, Lamb AN, Torchia BS, Bejjani BA, Shaffer LG (2009) Whole-genome microarray analysis in prenatal specimens identifies clinically significant chromosome alterations without increase in results of unclear significance compared to targeted microarray. Prenat Diagn 29(12):1156–1166. doi:10.1002/pd.2371

Cuckle HS, Wald NJ, Thompson SG (1987) Estimating a woman’s risk of having a pregnancy associated with Down’s syndrome using her age and serum alpha-fetoprotein level. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 94(5):387–402

Driscoll DA, Gross S (2009) Clinical practice. Prenatal screening for aneuploidy. N Engl J Med 360(24):2556–2562

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW (2005) Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Flint J, Wilkie AO, Buckle VJ, Winter RM, Holland AJ, McDermid HE (1995) The detection of subtelomeric chromosomal rearrangements in idiopathic mental retardation. Nat Genet 9(2):132–140

Grosse SD, Wordsworth S, Payne K (2008) Economic methods for valuing the outcomes of genetic testing: beyond cost-effectiveness analysis. Genet Med 10(9):648–654. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181837217

Lu XY, Phung MT, Shaw CA, Pham K, Neil SE, Patel A, Sahoo T, Bacino CA, Stankiewicz P, Kang SH, Lalani S, Chinault AC, Lupski JR, Cheung SW, Beaudet AL (2008) Genomic imbalances in neonates with birth defects: high detection rates by using chromosomal microarray analysis. Pediatrics 122(6):1310–1318

Macri JN, Kasturi RV, Krantz DA, Cook EJ (1991) Sensitivity and specificity of screening for Down syndrome with alpha-fetoprotein, hCG, unconjugated estriol, and maternal age. Obstet Gynecol 77(6):963–965

Mansfield ES (1993) Diagnosis of Down syndrome and other aneuploidies using quantitative polymerase chain reaction and small tandem repeat polymorphisms. Hum Mol Genet 2(1):43–50

Maya I, Davidov B, Gershovitz L, Zalzstein Y, Taub E, Coppinger J, Shaffer LG, Shohat M (2010) Diagnostic utility of array-based comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) in a prenatal setting. Prenat Diagn 30(12–13):1131–1137. doi:10.1002/pd.2626

Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, Biesecker LG, Brothman AR, Carter NP, Church DM, Crolla JA, Eichler EE, Epstein CJ, Faucett WA, Feuk L, Friedman JM, Hamosh A, Jackson L, Kaminsky EB, Kok K, Krantz ID, Kuhn RM, Lee C, Ostell JM, Rosenberg C, Scherer SW, Spinner NB, Stavropoulos DJ, Tepperberg JH, Thorland EC, Vermeesch JR, Waggoner DJ, Watson MS, Martin CL, Ledbetter DH (2010) Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet 86(5):749–764

MRC working party on the evaluation of chorion villus sampling (1991) Medical Research Council European trial of chorion villus sampling. Lancet 337 (8756):1491–1499

Pertl B, Yau SC, Sherlock J, Davies AF, Mathew CG, Adinolfi M (1994) Rapid molecular method for prenatal detection of Down’s syndrome. Lancet 343(8907):1197–1198

Regier DA, Friedman JM, Marra CA (2010) Value for money? Array genomic hybridization for diagnostic testing for genetic causes of intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet 86(5):765–772. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.009

Sahoo T, Cheung SW, Ward P, Darilek S, Patel A, del Gaudio D, Kang SH, Lalani SR, Li J, McAdoo S, Burke A, Shaw CA, Stankiewicz P, Chinault AC, Van den Veyver IB, Roa BB, Beaudet AL, Eng CM (2006) Prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities using array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Genet Med 8(11):719–727

Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G (2002) Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res 30(12):e57

Shaffer LG, Bui TH (2007) Molecular cytogenetic and rapid aneuploidy detection methods in prenatal diagnosis. Am J Med Genet 145C(1):87–98

Steele MW, Breg WR Jr (1966) Chromosome analysis of human amniotic-fluid cells. Lancet 1(7434):383–385

Tabor A, Philip J, Madsen M, Bang J, Obel EB, Norgaard-Pedersen B (1986) Randomised controlled trial of genetic amniocentesis in 4606 low-risk women. Lancet 1(8493):1287–1293

Van den Veyver IB, Patel A, Shaw CA, Pursley AN, Kang SH, Simovich MJ, Ward PA, Darilek S, Johnson A, Neill SE, Bi W, White LD, Eng CM, Lupski JR, Cheung SW, Beaudet AL (2009) Clinical use of array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) for prenatal diagnosis in 300 cases. Prenat Diagn 29(1):29–39

Wald NJ, Cuckle HS, Densem JW, Nanchahal K, Royston P, Chard T, Haddow JE, Knight GJ, Palomaki GE, Canick JA (1988) Maternal serum screening for Down’s syndrome in early pregnancy. BMJ (Clin Res ed) 297 (6653):883–887

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the support of the medical geneticists and obstetricians in both hospitals, Drs. M. del Campo, T. Vendrell, A. Cueto, S. García-Miñaúr, M.A. Sánchez, J. Sagalá, M.T. Higueras, E. Carreras, R. Rodríguez, A. González, F. Herrero, as well as all participants. Thanks to Dr. J.R. González for statistical support and critical review and A. Fernández, M. Arranz and R. Sansegundo for technical assistance. We thank P. Serrano-Aguilar for assistance with economical aspects. This work was supported by a grant from the Spanish Agency for Evaluation of Novel Sanitary Technologies (AETS-PI08/90056).

Conflict of interest

Lluís Armengol and Luis Pérez-Jurado are executive director and scientific advisor, respectively, of qGenomics, a privately held company that provide genomics services to the scientific and medical community.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Armengol, L., Nevado, J., Serra-Juhé, C. et al. Clinical utility of chromosomal microarray analysis in invasive prenatal diagnosis. Hum Genet 131, 513–523 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-011-1095-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-011-1095-5