Abstract

Objective

Since 2011, noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) has undergone rapid expansion, with both utilization and coverage. However, conclusive data regarding the clinical validity and utility of this testing tool are lacking. Thus, there is a continued need to educate clinicians and patients about the current benefits and limitations in order to inform pre- and post-test counseling, pre/perinatal decision making, and medical risk assessment/management.

Methods

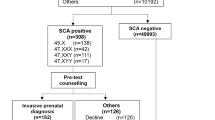

This retrospective study included women referred for invasive prenatal diagnosis to confirm positive NIPT results between January 2017 and December 2020. Prenatal diagnosis testing, including karyotyping, chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) were performed. Positive predictive values (PPVs) were calculated.

Results

In total, 468 women were recruited. The PPVs for trisomies 21, 18, and 13 were 86.1%, 57.8%, and 25.0%, respectively. The PPVs for rare chromosomal abnormalities (RCAs) and copy number variants (CNVs) were 17.0% and 40.4%, respectively. The detection of sex chromosomal aneuploidies (SCAs) had a PPV of 20% for monosomy X, 23.5% for 47,XXX, 68.8% for 47,XXY, and 62.5% for 47,XYY. The high-risk groups had a significant increase in the number of true positive cases compared to the low- and moderate-risk groups.

Conclusions

T13, monosomy X, and RCA were associated with lower PPVs. The improvement of cell-free fetal DNA screening technology and continued monitoring of its performance are important.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1997, cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) was first detected in the plasma of pregnant women. In 2008, massively parallel sequencing (MPS) was introduced as a new approach to non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for fetal chromosomal aneuploidies [1, 2]. Several studies have shown that the NIPT has superior sensitivity and specificity to maternal serum screening for detecting trisomy 21 (T21, Down’s syndrome), trisomy 18 (T18, Edward’s syndrome), and trisomy 13 (T13, Patau syndrome) [3,4,5]. Over the last few years, NIPT has become the most common and first-choice screening test for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Millions of pregnant women have undergone NIPT to identify the potential presence of T21, T18, and T13 in their fetuses, particularly in China [6,7,8,9,10]. NIPT has expanded to include sex chromosomal aneuploidies (SCAs), rare chromosomal aneuploidies (RCAs), and copy number variants (CNVs), although the specificity for detecting SCAs is low, and the accuracy rate for detecting RCAs/CNVs has not been well validated [9,10,11].

NIPT is not a diagnostic test because it measures a mixture of fetal and maternal DNA, and there is a chance of a false-positive or false-negative result, particularly for SCAs, RCAs, and CNVs. A positive result should always be confirmed with an invasive diagnostic test using amniotic fluid, chorionic villi, or umbilical cord blood. As NIPT becomes the first-tier screening test for fetal trisomies 21, 18, and 13 and other chromosomal aberrations, more studies of its validity are needed to guide clinicians regarding when to recommend testing and how to interpret the results. In the current study, we retrospectively examined 468 confirmatory diagnostic studies performed on patients who had received abnormal high-risk NIPT results and reviewed the related literatures.

Materials and methods

Participant recruitment

We retrospectively collected data from patients who underwent prenatal diagnosis at our laboratory owing to positive NIPT results. Data were collected between January 2017 and December 2020. Some initial NIPT was conducted at our laboratory, where as in other cases, it was performed by a variety of commercial laboratories, including BGI or Darui, or referred from other hospitals, according to their specific methodologies. For cases of NIPT performed in our laboratory, all DNA libraries were constructed from maternal plasma and subjected to MPS on the Nextseq500 (CN500) platform. Sequence reads were aligned to the human genomic sequence hg19 [12], and uniquely mapped reads were counted and normalized for GC content [6].The test sample data were finally compared to reference sample data, and Z-scores were calculated to determine chromosomal ploidy using the normal range, − 3.0 < Z < 3.0 [2]. Pregnant women with positive NIPT results were advised to undergo invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures (e.g., chorionic villus sampling [CVS]) at 10–15 weeks, amniocentesis at 16–24 weeks, or cordocentesis when the gestational age was beyond 24 weeks.

Prenatal diagnosis

All the enrolled participants underwent an invasive diagnosis at our laboratory. The accuracy of NIPT was confirmed by karyotype analysis and chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), which were performed in all cases with NIPT showing suspected CNV abnormalities. Karyotyping was carried out according to the conventional G-banding method. CMA was performed using a commercial SNP array chip, the Human omni-zhonghua-8 BeadChip (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Aneuploid cases categorized as true positives (TPs) included those with complete concordance as well as those with partial concordance (i.e., NIPT positive for T18, confirmatory testing demonstrating trisomy for a portion of chromosome 18), those having a micro-duplication on the same chromosome by CMA, and those having incomplete concordance (i.e., NIPT positive for both T13 and T18, confirmatory testing demonstrated byT13 only). False-positive (FP)cases were defined as those with complete discordance between NIPT and confirmatory testing (i.e., NIPT positive for chr8 but with a normal karyotype and CMA demonstrating 6q27 micro-deletion).The positive predictive value (PPV) was calculated as the number of cases for which NIPT and confirmatory diagnostic testing were concordant (TP cases) divided by the number of cases with positive NIPT results (TP + FP cases) multiplied by 100.

Data analysis and statistics

Advanced maternal age (AMA), abnormal fetal ultrasound, and adverse pregnancy history contribute to a high risk of chromosomal aneuploidies. In this study, we classified these NIPT-positive cases into three subgroups according to whether the risk of fetal abnormality was low, moderate, or high. High risk was defined as AMA, a high risk of serum screening, structural abnormality on fetal ultrasound, or a history of previous abnormal fetal pregnancy. Moderate risk was defined as the presence of ultrasound soft markers or critical risk based on serum screening. Low risk was defined as none of these known high-risk factors. The high-risk group was subdivided into two groups with one factor and two more factors. Maternal age plays an important role in fetal abnormalities, and we also classified women into AMA (≥ 35 years) and younger women. All data analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences in proportions were tested for statistical significance using the chi-square test, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

To conduct a literature review on PPVs of NIPT, a non-systematic targeted search was performed using PubMed/Medline. The keywords used were [NIPT], [non-invasive prenatal testing], [NIPS], and [non-invasive prenatal screening]. Relevant articles with more than 30,000 samples from China and 10,000 from other countries were reviewed. The search for articles progressed as the study was being completed, including additional studies identified by manually searching the references of the included articles.

Results

Characteristics of subjects

A total of 468 women with positive NIPT results received a prenatal diagnosis at the laboratory from January 2017 to December 2020, including 444 cases of amniocentesis (94.9%), 18 cases of cordocentesis (3.8%), and 6 cases of CVS (1.3%). These pregnant women were 17–47 years old, and the mean age was 31.7 ± 6.0 years (median 31). A total of 171 women (36.5%) were of advanced maternal age (AMA), 70 (15.0%) had maternal serum screening showing high-risk results, 146(31.2%) had ultrasound soft markers, and 59 (12.6%) had ultrasound structural abnormalities. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the patients. The serum screening cut-offs for high-risk for T21 and T18 were 1/270 and 1/350, respectively, and the critical risk values were 1/271-1/1000 and 1/351-1/1000, respectively.

Cases of suspected aneuploidy

Of the 468 cases, 217 (46.4%) were common autosomal trisomies 146 (31.2%), 53 (11.3%), and 52 (11.1%) cases of T21, T18, and T13, respectively. A total of 203 TP and 166 FP cases were confirmed through invasive diagnosis. The PPVs for T21, T18, and T13 were 86.1, 57.8, and 25.0%, respectively. For the SCAs, monosomy X had the most NIPT-positive cases, while the lowest PPV was 20.0%. The PPV of XXY was the highest (68.8%), followed by that of XYY (62.5%) (Table 2).

Our study also included 53 patients with positive NIPT results for less common aneuploidies (i.e., monosomies 13 and 18 and trisomies for chromosomes 3, 7, 8, and 16). NIPT-positive cases of RCAs involved all rare chromosomes except chromosome 15 and chromosome 17, whereas chromosome 7 (10 cases) and chromosome 8 (8 cases) were involved in most RCA cases, followed by chromosome 16 (7 cases) and chromosome 3 (6 cases). In total, for RCAs, which exhibited the lowest PPV (17.0%), 9 TPs in 53cases were confirmed. These TP cases included one case of trisomy 7 (mosaic), one case of trisomy 9 (mosaic), one case of trisomy 12 (mosaic), and other cases with CMA results showing duplication or deletion on related chromosomes.

Cases of suspected chromosomal deletion/duplication

Among the 52 NIPT-positive CNVs, 21 TP CNV cases were identified, and the PPV of CNVs was 40.4%.The most frequent micro-deletions in our data set were the Prader-Willi syndrome/Angelman syndrome region (PWS/AS, 15q11.2-q13.1), DiGeorge syndrome deletion (DGS, 22q11.2), Cri-du-chat syndrome region (CDC, 5pter), and del 1p36. Of the 11 cases with positive NIPT results for these recurrent regions, only one case (CDC) was confirmed. The 21 validated deletions/duplications are shown in Table 3. Among the 21 validated CNV cases, 6 CNVs were larger than 10 Mb, 4 CNVs were between 5 and 10 Mb, and 11 were smaller than 5 Mb in size. Here, we evaluated the PPV for detecting chromosomal deletions/duplications at a size of > 10 Mb, between 5 and 10 Mb, and < 5 Mb as 37.5%, 44.4%, and 44.0%, respectively.

NIPT accuracy with other risk factors and serum screening

P-values were calculated to compare TP and FP case distributions among the different risk groups (Table 4). The number of TP cases increased significantly in the two high-risk groups, comprising 54.0% and 87.5%, respectively, whereas these values were only 32.0% and 39.6% in the low- and moderate-risk groups, respectively. Significant differences between the low-and high-risk groups were found (P-values < 0.001), but no significant difference was observed between the low- and moderate-risk groups (P = 0.276). T21/T18/T13 showed similar TP and FP case distributions, and TP cases comprised 72.5% and 97.1% of the high-risk groups with one and two or more factors, respectively, compared to the low-risk group (36.4%) and moderate-risk groups (57.1%), both of which were significantly different (P < 0.001). No significant difference was observed between the low- and moderate-risk groups (P = 0.086) (Table 4).

Of the 171 AMA cases, there were 111 TP cases (PPV, 64.9%) and 60 FP cases, while in the group of women < 35 years, 136 TP (PPV, 45.8%) and 161 FP cases were confirmed (P < 0.001). Significant increases in TP% were also observed in the AMA group compared to the younger female group for T21/T18/T13 (P < 0.001).

Of the 468 cases, 179 cases (38.2%) had a serum screening result, including 71 cases of high risk, 52 cases of moderate risk, and 56 cases of low risk. The PPVs were 70.4% in high risk serum screening result group, 48.1% in moderate risk serum screening, and 48.2% in low risk serum screening result. Significant differences between the low-and high-serum screening risk groups were found (P-values = 0.011).

Discussion

In this study, we presented the PPVs for NIPT of different types of aneuploidies, including T21, T18, T13, SCAs, RCAs, and CNVs. Here, we summarized previously reported literature on PPVs for NIPT, using data collected from 2015 (Table 5). These data were mostly from China [8,9,10, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] and the United States [23, 27], the Netherlands [24], Japan [22], Iran [25], and Italy [21, 26]. The PPVs presented in this study were consistent with those in previous reports (Table 5) [9, 15,16,17, 19, 20]. PPVs for T21 were higher than 84% in most reports, while only two reports had PPVs lower than 80% [10, 14]. These two reports also showed lower PPVs for other aneuploidies. After reviewing the literature, we found that they both conducted sequencing using the JingXin Bioelectron Seq 4000 System (CFDA registration permit No. 20153400309). The lower PPVs may be caused by the sequence-read depths and algorithms provided by the system. Most reports from China show PPVs of T21 ranging from 80 to 92%, which is consistent with our study [8, 9, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Reports from outside China also showed higher PPVs for T21, ranging from 95.7 to 99.2% [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. These reports from China showed higher PPVs on T18, T13, and SCAs, which we believe was caused by the participant women having a higher risk for aneuploidies; the mean age was 35.3 years in a report from Italy [21], and the average maternal age was 34 years in a report from the USA [27], while the mean age was 31 years in this study. The PPVs of T18 ranged from 45 to 82% in most reports, except for reports of high-risk populations with higher PPVs [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. For T13, the PPVs were lower than 50% in studies based on the Chinese population and some similar reports [8,9,10, 14, 15, 18,19,20]. The PPVs for RCAs were lower than 28%, which may be due to the low prevalence of the disorder, except for in one study with a high-risk population [21]. For CNVs, the PPVs ranged from 29 to 50%, except in one study with a high-risk population [27]. Differences in PPVs between studies occur because study populations differ in size, demographics, and clinical characteristics, and different NIPT platforms with variable sequence read depths and algorithms are used by different providers. We also summarized the PPVs of SCAs in Tables 6 and 45X had the lowest PPVs, ranging from 14 to 29% in the general population [9, 13, 16, 28, 29]. The PPVs of XXX, XXY, and XYY varied greatly, which we believe was due to the small number of sex aneuploidies in each study. PPV is a population-based figure that reports the chance that a positive NIPT result is reflective of the karyotype of the fetus, and PPVs are involved with the prevalence of a disorder [31]. Thus, it is vital to educate ordering physicians regarding the differences between specificity and PPV. Sensitivity indicates the chance that a test result will be positive for a given disorder; specificity measures the chance that a fetus, which does not have a particular aneuploidy, will test negative for that aneuploidy. Neither sensitivity nor specificity reflected the prevalence of a disorder in the population; however, PPV did. For an average clinician, the claim that a test is > 99% specific leads him or her to expect a false-positive rate of < 1%. As we can see in the study and other previous reports, the ability of NIPT to correctly predict a positive result for T18 is less than 80% and less than 50% for T13, monosomy X, and RCAs. The study revealed that a significant increase in PPVs was found in high-risk groups with one factor and two or more factors, which also indicates that women with AMA, along with other high-risk factors, such as having a high-risk serum screening result, can undergo invasive diagnosis and not other screening. While in the study, before taking NIPT, there were 179 cases (38.2%) having a serum screening result, including 71 cases of high risk.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published the clinical management guidelines for screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities in 2020, stated that patients should have one prenatal screening approach and should not have multiple screening tests performed simultaneously [31]. Another study also reported that NIPT should not be recommended for pregnancies with ultrasound anomalies or high-risk pregnancies, even the expanded NIPT [32, 33]. Nonetheless, some pregnant women consider NIPT an acceptable alternative to invasive diagnostic testing. For post counseling, in regard to current NIPT guidelines, the ACMG strongly suggests invasive prenatal testing to confirm all positive findings [34, 35].

Conclusions

In conclusion, we evaluated and summarized the PPVs of all aneuploidies using NIPT in this study and in previous publications. The NIPT is fundamentally a screening test and cannot be used as a replacement for invasive prenatal diagnosis. Based on the study findings, we hope to raise concerns about the limitations of NIPT. Furthermore, we have to ensure that clinicians interpret the NIPT results correctly and provide more careful and precise counsel so that pregnant women can make a more informed decision based on scientific data and knowledge.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NIPT:

-

Noninvasive prenatal testing

- CMA:

-

Chromosomal microarray analysis

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- cffDNA:

-

Cell-free fetal DNA

- SCA:

-

Sex chromosomal aneuploidies

- RCA:

-

Rare chromosomal aneuploidies

- CNV:

-

Copy number variants

- CVS:

-

Chorionic villus sampling

References

Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, et al. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):485–7.

Chiu RW, Chan KC, Gao Y, et al. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of fetal chromosomal aneuploidy by massively parallel genomic sequencing of DNA in maternal plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(51):20458–63.

Bianchi DW, Parker RL, Wentworth J, CARE Study Group, et al. DNA sequencing versus standard prenatal aneuploidy screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):799–808.

Taylor-Phillips S, Freeman K, Geppert J, et al. Accuracy of non-invasive prenatal testing using cell-free DNA for detection of Down, Edwards and Patau syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010002.

Gil MM, Accurti V, Santacruz B, Plana MN, Nicolaides KH. Analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal blood in screening for aneuploidies: updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(3):302–14. Update in: Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53(6):734–42.

Liang D, Lv W, Wang H, et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing of fetal whole chromosome aneuploidy by massively parallel sequencing. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(5):409–15.

Song Y, Liu C, Qi H, et al. Noninvasive prenatal testing of fetal aneuploidies by massively parallel sequencing in a prospective Chinese population. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(7):700–6.

Zhang H, Gao Y, Jiang F, et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing for trisomies 21, 18 and 13: clinical experience from 146,958 pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45(5):530–8. Erratum in: Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(1):130.

Xue Y, Zhao G, Li H, et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing to detect chromosome aneuploidies in 57,204 pregnancies. Mol Cytogenet. 2019;12:29.

Chen Y, Yu Q, Mao X, et al. Noninvasive prenatal testing for chromosome aneuploidies and subchromosomal microdeletions/microduplications in a cohort of 42,910 single pregnancies with different clinical features. Hum Genomics. 2019;13(1):60.

Suo F, Wang C, Liu T, et al. Non-invasive prenatal testing in detecting sex chromosome aneuploidy: a large-scale study in Xuzhou area of China. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;481:139–41.

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(5):589–95.

Liang D, Cram DS, Tan H, et al. Clinical utility of noninvasive prenatal screening for expanded chromosome disease syndromes. Genet Med. 2019;21(9):1998–2006.

Liu Y, Liu H, He Y, et al. Clinical performance of non-invasive prenatal served as a first-tier screening test for trisomy 21, 18, 13 and sex chromosome aneuploidy in a pilot city in China. Hum Genomics. 2020;14(1):21.

Luo Y, Hu H, Jiang L, et al. A retrospective analysis the clinic data and follow-up of non-invasive prenatal test in detection of fetal chromosomal aneuploidy in more than 40,000 cases in a single prenatal diagnosis center. Eur J Med Genet. 2020;63(9):104001.

Xu L, Huang H, Lin N, et al. Non-invasive cell-free fetal DNA testing for aneuploidy: multicenter study of 31 515 singleton pregnancies in southeastern China. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(2):242–7.

Lu W, Huang T, Wang XR, et al. Next-generation sequencing: a follow-up of 36,913 singleton pregnancies with noninvasive prenatal testing in central China. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37(12):3143–50.

Xu H. Retrospective analysis of 44 578 pregnancies undergoing non-invasive prenatal testing in Weifang. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2020;37(10):1065–1068 (in Chinese).

Shi P, Wang Y, Liang H, et al. The potential of expanded noninvasive prenatal screening for detection of microdeletion and microduplication syndromes. Prenat Diagn. 2021;41(10):1332–42.

Wang C, Tang J, Tong K, et al. Expanding the application of non-invasive prenatal testing in the detection of foetal chromosomal copy number variations. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14(1):292.

Fiorentino F, Bono S, Pizzuti F, et al. The clinical utility of genome-wide non invasive prenatal screening. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(6):593–601.

Samura O, Sekizawa A, Suzumori N, et al. Current status of non-invasive prenatal testing in Japan. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(8):1245–55.

Guy C, Haji-Sheikhi F, Rowland CM, et al. Prenatal cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy in pregnant women at average or high risk: results from a large US clinical laboratory. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(3):e545.

van der Meij KRM, Sistermans EA, Macville MVE, et al. TRIDENT-2: national implementation of genome-wide non-invasive prenatal testing as a first-tier screening test in the Netherlands. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105(6):1091–101.

Garshasbi M, Wang Y, Hantoosh Zadeh S, et al. Clinical application of cell-free DNA sequencing-based noninvasive prenatal testing for trisomies 21, 18, 13 and sex chromosome aneuploidy in a mixed-risk population in Iran. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2020;47(3):220–7.

La Verde M, De Falco L, Torella A, et al. Performance of cell-free DNA sequencing-based non-invasive prenatal testing: experience on 36,456 singleton and multiple pregnancies. BMC Med Genomics. 2021;14(1):93.

Soster E, Boomer T, Hicks S, et al. Three years of clinical experience with a genome-wide cfDNA screening test for aneuploidies and copy-number variants. Genet Med. 2021;23(7):1349–55. Erratum in: Genet Med. 2021.

Xu Y, Chen L, Liu Y, et al. Screening, prenatal diagnosis, and prenatal decision for sex chromosome aneuploidy. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2019;19(6):537–42.

Deng C, Zhu Q, Liu S, et al. Clinical application of noninvasive prenatal screening for sex chromosome aneuploidies in 50,301 pregnancies: initial experience in a Chinese hospital. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7767.

Lüthgens K, Grati FR, Sinzel M, Häbig K, Kagan KO. Confirmation rate of cell free DNA screening for sex chromosomal abnormalities according to the method of confirmatory testing. Prenat Diagn. 2021;41(10):1258–63.

Screening for Fetal Chromosomal Abnormalities. ACOG practice bulletin summary, number 226. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(4):859–67.

Beulen L, Faas BHW, Feenstra I, van Vugt JMG, Bekker MN. Clinical utility of non-invasive prenatal testing in pregnancies with ultrasound anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(6):721–8.

Zhu X, Chen M, Wang H, et al. Clinical utility of expanded non-invasive prenatal screening and chromosomal microarray analysis in high-risk pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57(3):459–65.

Gregg AR, Skotko BG, Benkendorf JL, et al. Noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy, 2016 update: a position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2016;18(10):1056–65.

Cherry AM, Akkari YM, Barr KM, et al. Diagnostic cytogenetic testing following positive noninvasive prenatal screening results: a clinical laboratory practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2017;19(8):845–50.

Acknowledgements

No applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou, China (201604020104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL and FY conceived the analysis. FL drafted the manuscript. SL, YX, XF reviewed NIPT results. RW, WC, FH performed the validation experiments. FY, QC, BJ, LL and AY performed clinical diagnosis, communication with patients. FL followed the pregnancy outcome. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital (approval no. NFEC-2017-035) and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Yang, F., Chang, Q. et al. Positive predictive value estimates for noninvasive prenatal testing from data of a prenatal diagnosis laboratory and literature review. Mol Cytogenet 15, 29 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-022-00607-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-022-00607-z