Abstract

The aim of this work was to analyse the characteristics of Questions and Answers (Q&As) at a drug information centre (DIC) regarding drug related problems and off-label drug treatment in children. All questions concerning children 15 years or younger at a DIC in Stockholm, Sweden during the years 1995–2004 were analysed with respect to the main drug related problem, drug/s and drug group/s, whether the drugs were licensed or not, pediatric labelling of the drug/s and age and sex of the patient. Q&As were classified as whether or not they included evaluated literature information, adding to the labelling of the drugs. We identified 249 Q&As concerning pediatric drug treatment. Each question addressed an average of 1.5 drugs. More than two-thirds of the Q&As concerned adverse drug reactions and pediatric drug choice or dosing. Every second question was classified as off-label, psychotropic drugs being the most common. In half of all off-label Q&As, pediatric documentation on drug efficacy and safety outside the Swedish catalogue of medical products was found. Most Q&As concerned newborns and infants. However, the off-label proportion among questions was highest in adolescence as well as the evaluated literature information, adding to the labelling of the drugs. It was thus found that off-label drug treatment is common among pediatric questions at a DIC. This service can provide additional literature based information contributing to a safer use of drugs in children. There is still, however, a substantial need for clinical documentation of drug use in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children, and especially small children, receive considerable amounts of drugs [16, 21, 24, 27] and several studies indicate that drug related problems in children are of great clinical relevance and that many of them are preventable [7, 12, 25].

Drug prescribing in children has been reported to frequently be carried out in an off-label and/or unlicensed manner, both in hospitals and in primary health care [20, 26, 27]. The term off-label in these studies is defined as the use of a drug outside the terms of the product license for children and unlicensed drugs are drugs that do not have a product license.

The licensing procedure is mainly based on clinical trials in adults and aims at ensuring the safety, efficacy and quality of drugs. However, children differ from adults regarding pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [30]. The lack of clinical trials in children results in non-existing pediatric labelling of many drugs and off-label pediatric drug use. Attempts have been made by the medical regulatory agencies to stimulate the drug industry to perform pediatric clinical trials [6]. However, an investigation of the license status of drugs approved after these initiatives were implemented shows that the majority of the drugs still lack pediatric labelling [11]. Off-label drug treatment has been associated with an increased frequency of ADRs compared with licensed pediatric drug treatment [13, 28].

Since readily available information concerning pediatric drug treatment from clinical trials and drug producers are scarce, other sources of information, such as what might be found at drug information centres (DICs), are needed.

The first DIC in Sweden was established in 1974, through a co-operation of clinical pharmacologists and information pharmacists [2]. Today, there is a regional network of DICs in Swedish university hospitals [18]. The DICs in Sweden offer evidence based drug information, comparable to clinical consultations, to drug prescribing health professionals [2, 18]. There are several DICs established in other European countries with similar working methods [18, 22].

We have found no published study on pediatric drug treatment based on data from a DIC. However, three studies concerning drug use in pregnancy or breast-feeding based on data from DICs concluded that the DIC is an important source of evidence based information [1, 9, 14].

The aim of this study was to analyse the characteristics of Questions and Answers (Q&As) at a drug information centre regarding drug related problems and off-label drug treatment in children and also to analyse how often the DIC could provide evaluated information concerning pediatric drug use, in addition to the information available in the Swedish catalogue of medical products.

Methods

Settings and subjects

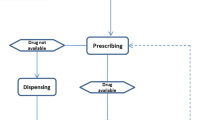

A register of all Q&As handled by the DIC at the Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, was used as the information source for this study [2, 18]. When a question is asked, a literature search is performed at the DIC, the available information is evaluated and initially a preliminary answer is given. The most frequent literature sources used are medical databases, e.g. Medline, handbooks, e.g. Martindale, and contacts with relevant authorities, e.g. medical products agency or the manufacturer. After internal review and approval at a weekly staff meeting a written answer with references is sent to the requester [18]. All Q&As are continuously registered in a local database, Dataease, which contains information concerning question date, questioner, demographic data, drug and medical history of the patient, and the drug related problem in question (adverse reaction, interaction, kinetics, drug choice and/or dosing, or drug formulation and/or administration) and the answer delivered with literature references [2, 18]. The Q&As of general interest are put into an international database, Drugline, that is continually updated by the DICs in Sweden, Odense Denmark and Åbo, Finland [19].

All Q&As concerning children during a ten-year period, from 1995 to 2004, were retrieved and systematically analysed. Out of a total of 6,842 Q&As that were handled at the DIC during this period, 300 (4.4%) concerned children. The further analysis was restricted to Q&As concerning children 15 years or younger. Fifty-one Q&As (17%) were excluded from further analysis since they concerned breast-feeding and/or pregnancy, patients 16 years or older, food, chemicals or doping or accidental ingestion of drugs.

Classification

The questions were analysed and classified with respect to the main drug related problem, drug/s and drug group/s, pediatric labelling of the drug at the time the question was raised, and age and sex of the patient (if known). Answers relating to off-label treatment with drugs licensed in Sweden were analysed with respect to their content of evaluated literature information, adding to the information given in the labelling of the drugs.

The off-label assessment was performed by using the Swedish catalogue of medical products (FASS) from the same year as the question [10]. A question was regarded as off-label if any of the drugs was explicitly not recommended, or was given for an unproven indication, dose and/or age-group in children. Questions concerning drugs for which no information about the mode of pediatric use in the patient was available, or for which safety and efficacy studies had not been performed in a pediatric population, were also regarded as off-label. All drugs that were not listed in FASS were classified as unlicensed, e.g. drugs prescribed on license bases or herbal remedies. The licensed drugs were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system (ATC) up to the 5th level [29]. The register contains no references to patient identity and therefore no ethical approval was needed for the study.

Results

A total of 249 Q&As concerning children 15 years or younger were identified, most of which originated from hospital care (82%) and related to systemic drug exposure (98%). Each question concerned an average of 1.5 drugs or herbal remedies. More than half of the questions concerned use of drugs in an off-label (31%) or unlicensed (24%) manner. The most common reason for off-label classification of drugs was lack of pediatric labelling (53%), followed by lack of safety and efficacy studies performed in children (23%). As for the answers to questions regarding off-label treatment, more than half (53%) were classified as containing evaluated literature information adding to the labelling of the drugs.

Table 1 gives the proportion of drug related problems addressed for all the questions, and also for the groups of questions concerning unlicensed or off-label drug use. The last column gives the proportion of answers (to off-label questions) containing information not included in the labelling of the drugs, in relation to the type of drug related problem.

Adverse drug reactions was the most common type of drug related problem referred to in the questions (Table 1). The most common types of adverse reactions were signs and symptoms from the central nervous system (19%, e.g. neuropathy or prolonged anesthesia), hematological reactions (15%, e.g. thrombocytopenia or leucopenia) and skin reactions (11%).

The majority of drugs (298 out of 372) included in the questions were licensed in Sweden. The most common therapeutic groups were antibacterial drugs for systemic use, antiepileptics, antidepressants, vaccines, and neuroleptics and sedatives (Table 2).

Psychotropic drugs, immunosuppressive agents and anti-inflammatory/antirheumatic agents were the drug groups most frequently associated with off-label questions (Table 2). Warfarin, risperidone, omeprazole, and different selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (all 3%) were the most common drugs associated with off-label questions.

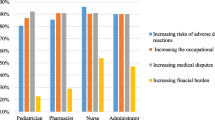

Questions concerning infants 0–1 years were most common (n = 41), with a proportion of off-label or unlicensed treatment of 12%. However, this proportion was highest for questions regarding adolescents (10–15 years) (33% of 68 questions). Literature information, adding to the information given in the labelling of drugs, was mainly found for adolescents (Fig. 1). (Unfortunately, in one third of the questions the age of the child was not specified or was not applicable in questions of a more general character).

Discussion

This study, analysing pediatric Q&As at a DIC, confirms that a large proportion of children, at least within hospital care, are treated with drugs in a way that is not supported by product labelling. In our data, we found that every second question concerned off-label or unlicensed drug treatment. Other hospital based studies have reported frequencies of off-label drug treatment between 36 and 92% in pediatric patients [20]. This large variation in the off-label frequency is partly explained by varying definitions of the term off-label between countries and studies.

The most common reason for a licensed drug in our questions to be classified as off-label was a lack of pediatric labelling. Again, this is in accordance with earlier findings [27]. However, the most important, and not previously reported, finding in the present study is the amount of information available through literature searching, that is apparently relevant to pediatric drug treatment, but that is not included in the product labelling of the drugs. For half of all the questions regarded as off-label, additional pediatric documentation was available from scientific publications found mainly in Medline, but also from other drug therapy literature sources, or through contact with the manufacturer. One reason for the large proportion of off-label drug treatment can thus be a lack of harmonisation between existing documentation in the literature and drug licenses. How can we make the best use of this information in pediatric health care, to improve the efficacy and safety of pediatric drug treatment? This finding does of course support the importance of a health care facility like the DIC, in providing condensed and evaluated literature information, supporting the treatment of individual patients. It has previously been shown that the DIC has a cost-saving potential in preventing ADRs [15]. The present finding also indicates the need, for example, of local or regional pediatric therapeutic expert groups to regularly survey the literature and distribute relevant new data and findings to all pediatric prescribers. The Internet can be of good use for this purpose, as exemplified by the Swedish webpage Janus (http://www.janusinfo.se), which is a non-commercial website, supported by the Stockholm county council, providing drug information to support health care professionals in their every day work.

In this context, it should be noted that a high proportion of off-label drug treatment is not necessarily synonymous with unsafe or incorrect pediatric treatment. It has been shown that physicians are well aware of the lack of pediatric labelling [8]. One reason for off-label drug use is that pediatricians have clinical experience that supports off-label drug use. Therefore, it is of great importance that such experience be documented and published as much as possible.

The present study, in finding that adverse drug reactions was the most common drug related problem, does also emphasize that pediatric adverse drug reactions are of great clinical relevance, in accordance with earlier studies [12, 25]. Adverse drug reactions were also often associated with off-label drug treatment, as previously shown [13, 28].

Psychotropic drugs was the most common therapeutic group of drugs in questions classified as off-label. This can partly be explained by an increased use of these drugs, e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), particularly in adolescents [3–5, 17, 23]. Recently, the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA) approved the use of fluoxetine in the treatment of depression in children eight years of age or older, who do not respond to psychotherapy. However, only one question in our material concerned fluoxetine.

We found some therapeutic drug groups that almost totally lacked pediatric labelling, i.e. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antithrombotic drugs. Especially for NSAIDs, more studies in the pediatric age group is warranted, as these drugs are prescribed to a large number of adult patients and can also be expected to have an impact on pediatric drug treatment. As for antithrombotic agents, these drugs have little use in the pediatric population. Nevertheless, antithrombotic drugs can be of great importance for a concerned group of pediatric patients.

Considering the lack of pediatric labelling for many drugs, we regard the DIC as an important complement to existing sources of drug information. The DICs also have the potential to prevent drug related problems through their pharmacological consultations. A future challenge is to continually spread existing evidence based knowledge regarding pediatric drug treatment to all physicians responsible for treating pediatric patients. Foremost, there is still a large need for increased research concerning pediatric drug treatment.

References

Addis A, Impicciatore P, Miglio D, Colombo F, Bonati M (1995) Drug use in pregnancy and lactation: the work of a regional drug information centre. Ann Pharmacother 29:632–633

Alván G, Öhman B, Sjöqvist F (1983) Problem oriented drug information: a clinical pharmacological service. Lancet 2:1410–1412

Bramness GJ, Hausken AM, Sakshaug S, Skurtveit S, Rønning M (2005) Prescription of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors 1990–2004. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 125:2470–2473 [in Norwegian]

Clavenna A, Bonati M, Rossi E, De Rosa M (2004) Increase in non-evidence based use of antidepressants in children is cause for concern. BMJ 328:711–712

Committee on Safety of Medicines (2006) Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), UK. Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk. Cited 01 March 2006

Conroy S (2002) Unlicensed and off-label drug use. Pediatr Drugs 4:353–359

Easton LK, Colin BC, Brien JE (2004) Frequency and characteristics of hospital admissions associated with drug-related problems in paediatrics. Br J Clin Pharmacol 57:611–615

Ekins-Daukes S, Helms PJ, Taylor MW, McLay JS (2005) Off-label prescribing to children: attitude and experience of general practitioners. Br J Clin Pharmacol 60:145–149

Elwin CE (1981) Trimethoprim- sulphamethoxazole during pregnancy. Experience of a follow-up of a register at a drug information centre. In: Nordbring F, Burman LG (eds) Urinary tract infections: current aspects of pathogenesis, prognosis and trimethoprim-sulphametoxazole therapy: proceeding of a Wellcome foundation symposium held in Stockholm, March 29–30,1979. Almqvist & Wiksell International, Stockholm, pp 109–115

FASS (2004) The Swedish catalogue of medical products, 1995–2004. LIF, Stockholm, Sweden

Impicciatore P, Choonara I (1999) Status of new medicines approved by the European medicines evaluation agency regarding paediatric use. Br J Clin Pharmacol 48:15–18

Impicciatore P, Choonara I, Clarkson A, Provasi A, Pandolfini C, Bonati M (2001) Incidence of adverse drug reactions in paediatric in/out-patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 52:77–83

Jonville-Béra AP, Béra F, Autret-Leca E (2005) Are incorrectly used drugs more frequently involved in adverse drug reactions? A prospective study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 61:231–236

Kasilo O, Romero M, Bonati M, Tognoni G (1988) Information on drug use in pregnancy from the viewpoint regional drug information centre. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 35:447–453

Lyrvall H, Nordin C, Jonsson E, Alvan G, Ohman B (1993) Potential savings of consulting a drug information centre. Ann Pharmacother 27:1540

Madsen H, Andersen M, Hallas J (2001) Drug prescribing among Danish children: a population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 57:159–165

Martin RM, Wilton LV, Mann RD, Steventon P, Hilton SR (1998) General practitioners prescribe SSRIs to children off-label. BMJ 317:204

Öhman B, Lyrvall H, Törnqvist E, Alván G, Sjöqvist F (1992) Clinical pharmacology and the provision of drug information. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 42:563–568

Öhman B, Lyrvall H, Alván G (1993) Use of Drugline—a question and answer database. Ann Pharmacother 27:278–284

Pandolfini C, Bonati M (2005) A literature review on off-label drug use in children. Eur J Pediatrics 164:552–558

Sanz EJ, Bergman U, Dahlstrom M (1989) Paediatric drug prescribing. A comparison of Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain) and Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 37:65–68

Schwartz S, Stoelben S, Ebert U, Siepmann M, Krappweis J, Kirch W (1999) Regional drug information service. Int J Clin Pharmacol Therap 37:263–268

Serreau R, Le Heuzey MF, Gilbert A, Mouren MC, Jacqz-Aigain E (2004) Unlicensed and off-label use of psychotropics medications in French children: a prospective study. Paediatr Perinatal Drug Ther 6:14–19

Straand J, Rokstad K, Heggedal U (1998) Drug prescribing for children in general practice. A report from the More and Romsadal prescription study. Acta Paediatr 87:218–224

Temple ME, Robinson RF, Miller JC, Hayes JR, Nahata MC (2004) Frequency and preventability of adverse drug reactions in paediatric patients. Drug Saf 27:819–829

‘tJong G, van der Linden P, Bakker E, van der Lely N, Eland I, Stricker B, van den Anker J (2002) Unlicensed and off-label drug use in a paediatric ward of a general hospital in the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 58:293–297

Ufer M, Rane A, Karlsson Å, Kimland E, Bergman U (2003) Widespread off-label prescribing of topical but not systemic drugs for 350,000 paediatric outpatients in Stockholm. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 58:779–783

Ufer M, Kimland E, Bergman U (2004) Adverse drug reactions and off-label prescribing for paediatric outpatients a one-year survey of spontaneous reports in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 13:147–152

WHO (2005) Collaborating centre for drug statistics methodology. About the ATC/DDD system [online]. Available at: http://www.whocc.no/atcddd/. Accessed 28 December 2005

Yaffe SJ, Aranda JV (eds) (2005) Neonatal and pediatric pharmacology: therapeutic principles in practice, 3rd edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia

Acknowledgement

To our colleagues at the DIC, Karolic, at the Karolinska University Hospital-Huddinge, who have contributed to the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kimland, E., Bergman, U., Lindemalm, S. et al. Drug related problems and off-label drug treatment in children as seen at a drug information centre. Eur J Pediatr 166, 527–532 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-006-0385-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-006-0385-8