Abstract

Pycnogonida (sea spiders) are bizarre marine arthropods that are nowadays most frequently considered as being the sister group to all other chelicerates. The majority of pycnogonid species develops via a protonymphon larva with only three pairs of limbs affiliated with the future head region. Deviating from this, the hatching stage of some representatives shows already an advanced degree of trunk differentiation. Using scanning electron microscopy, fluorescent nucleic staining, and bright-field stereomicroscopy, postembryonic development of Pseudopallene sp. (Callipallenidae), a pycnogonid with an advanced hatching stage, is described. Based on external morphology, six postembryonic stages plus a sub-adult stage are distinguished. The hatching larva is lecithotrophic and bears the chelifores as only functional appendage pair and unarticulated limb buds of walking leg pairs 1 and 2. Palpal and ovigeral larval limbs are absent. Differentiation of walking leg pairs 3 and 4 is sequential. Apart from the first pair, each walking leg goes through a characteristic sequence of three externally distinct stages with two intermittent molts (limb bud—seven podomeres—nine podomeres). First external signs of oviger development are detectable in postembryonic stage 3 bearing three articulated walking leg pairs. Following three more molts, the oviger has attained adult podomere composition. The advanced hatching stages of different callipallenids are compared and the inclusive term “walking leg-bearing larva” is suggested, as opposed to the behavior-based name “attaching larva”. Data on temporal and structural patterns of walking leg differentiation in other pycnogonids are reviewed and discussed. To facilitate comparisons of walking leg differentiation patterns across many species, we propose a concise notation in matrix fashion. Due to deviating structural patterns of oviger differentiation in another callipallenid species as well as within other pycnogonid taxa, evolutionary conservation of characteristic stages of oviger development is not apparent even in closely related species.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arabi J, Cruaud C, Couloux A, Hassanin A (2010) Studying sources of incongruence in arthropod molecular phylogenies: sea spiders (Pycnogonida) as a case study. C R Biol 333:438–453

Arango CP (2002) Morphological phylogenetics of the sea spiders (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida). Org Divers Evol 2:107–125

Arango CP, Wheeler WC (2007) Phylogeny of the sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) based on direct optimization of six loci and morphology. Cladistics 23:1–39

Arnaud F, Bamber RN (1987) The biology of Pycnogonida. Adv Mar Biol 24:1–96

Bain BA (2003a) Postembryonic development in the pycnogonid Austropallene cornigera (Family Callipallenidae). Invertebr Reprod Dev 43:181–192

Bain BA (2003b) Larval types and a summary of postembryonic development within the pycnogonids. Invertebr Reprod Dev 43:193–222

Bamber RN (2007) A holistic re-interpretation of the phylogeny of the Pycnogonida Latreille, 1810 (Arthropoda). Zootaxa 1668:295–312

Bamber RN, El Nagar A (2011) Pycnobase: World Pycnogonida Database. http://www.marinespecies.org/pycnobase

Behrens W (1984) Larvenentwicklung und Metamorphose von Pycnogonum litorale (Chelicerata, Pantopoda). Zoomorphology 104:266–279

Bogomolova EV (2007) Larvae of three sea spider species of the genus Nymphon (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida) from the White Sea. Russian J Mar Biol 33:145–160

Bogomolova EV (2010) Nymphon macronyx (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida), another pycnogonid species with “lecytotrophic protonymphon” development. Zool Zhurnal 89:528–544

Bogomolova EV, Malakhov VV (2003) Larvae of sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) from the White Sea. Entomol Rev 83:222–236

Bogomolova EV, Malakhov VV (2004) Fine morphology of larvae of sea spiders (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida) from the White Sea. Zool Bespozvon 1:3–28

Bogomolova EV, Malakhov VV (2006) Lecithotrophic protonymphon is a special type of postembryonic development of sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida). Dokl Biol Sci 409:328–331

Bourlat SJ, Nielsen C, Economou AD, Telford MJ (2008) Testing the new animal phylogeny: a phylum level molecular analysis of the animal kingdom. Mol Phylogenet Evol 49:23–31

Brenneis G, Ungerer P, Scholtz G (2008) The chelifores of sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) are the appendages of the deutocerebral segment. Evol Dev 10:717–724

Brenneis G, Arango CP, Scholtz G (2011) Morphogenesis of Pseudopallene sp. (Pycnogonida, Callipallenidae). I: embryonic development. Dev Genes Evol. doi:10.1007/s00427-011-0382-4

Burris ZP (2011) Larval morphologies and potential developmental modes of eight sea spider species (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida) from the southern Oregon coast. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 91:845–855

Cano Sánchez E, López-González PJ (2010) Postembryonic development of Nymphon unguiculatum Hodgson 1915 (Pycnogonida, Nymphonidae) from the South Shetland Islands (Antarctica). Polar Biol 33:1205–1214

Cano E, López-González PJ (2009) Novel mode of postembryonic development in Ammothea genus (Pycnogonida: Ammotheidae) from Antarctic waters. Sci Mar 73:541–550

Child CA (1979) Shallow water Pycnogonida of the Isthmus of Panama and the coasts of Middle America. Smithson Contrib Zool 23:1–86

Child CA (1998) The marine fauna of New Zealand: Pycnogonida (sea spiders). NIWA Biodivers Mem 109:1–71

Dearborn GK (2003) Post-embryonic development of the sea spider Achelia gracilipes (Chelicerata: Pycnogonida). Dep Biol Sci. Univ Alberta. Master Thesis. pp 1–86

Dogiel V (1913) Embryologische Studien an Pantopoden. Z Wiss Zool 107:575–741

Dohrn A (1881) Die Pantopoden des Golfes von Neapel und der angrenzenden Meeres-Abschnitte. Fauna und Flora des Golfes von Neapel. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig

Dunlop JA, Arango CP (2005) Pycnogonid affinities: a review. J Zool Syst Evol Res 43:8–21

Edgecombe GD, Wilson GDF, Colgan DJ, Gray MR, Cassis G (2000) Arthropod cladistics: combined analysis of histone H3 and U2 snRNA sequences and morphology. Cladistics 16:155–203

Gillespie JM, Bain BA (2006) Postembryonic development of Tanystylum bealensis (Pycnogonida, Ammotheidae) from Barkley Sound, British Columbia, Canada. J Morphol 267:308–317

Giribet G, Edgecombe GD, Wheeler WC (2001) Arthropod phylogeny based on eight molecular loci and morphology. Nature 413:157–161

Hedgpeth JW (1947) On the evolutionary significance of the Pycnogonida. Smithson Misc Coll 106:1–53

Hoek PPC (1881) Report on the Pycnogonida, dredged by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76. Zool Chall Exp 10:1–167

Hooper J (1980) Some aspects of the reproductive biology of Parapallene avida Stock (Pycnogonida: Callipallenidae) from Northern New South Wales. Aust Zool 30:473–483

Koenemann S, Jenner RA, Hoenemann M, Stemme T, von Reumont BM (2010) Arthropod phylogeny revisited, with a focus on crustacean relationships. Arthropod Struct Dev 39:88–110

Lebour MV (1916) Notes on the life history of Anaphia petiolata (Kröyer). J Mar Biol Assoc UK 11:51–56

Lebour MV (1945) Notes on the Pycnogonida of Plymouth. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 26:139–165

Lovely EC (2005) The life history of Phoxichilidium tubulariae (Pycnogonida: Phoxichilidiidae). Northeast Nat 12:77–92

Machner J, Scholtz G (2010) A scanning electron microscopy study of the embryonic development of Pycnogonum litorale (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida). J Morphol 271:1306–1318

Maxmen A (2006) Pycnogonid development and the evolution of the arthropod body plan. Harvard Univ, Cambridge, Massachusetts. PhD Thesis. pp 1–177

Meinert F (1899) Pycnogonida. The Danish Ingolf-Expedition. Bianco Luno (F. Dreyer), Copenhagen

Meisenheimer J (1902) Beiträge zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Pantopoden. I. Die Entwicklung von Ammothea echinata Hodge bis zur Ausbildung der Larvenform. Z Wiss Zool 72:191–248

Meusemann K, von Reumont BM, Simon S, Roeding F, Strauss S, Kück P, Ebersberger I, Walzl M, Pass G, Breuers S, Achter V, von Haeseler A, Burmester T, Hadrys H, Wägele JW, Misof B (2010) A phylogenomic approach to resolve the arthropod tree of life. Mol Biol Evol 27:2451–2464

Morgan TH (1891) A contribution to the embryology and phylogeny of the pycnogonids. Stud Biol Lab Johns Hopkins Univ 5:1–76

Munilla T (1999) Evolución y filogenia de los picnogónidos. In: Melic A, de Haro JJ, Mendez M, Ribera I (eds) Evolución y filogenia de Arthropoda. Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa, Zaragoza, pp 273–279

Nakamura K (1981) Post-embryonic development of a pycnogonid, Propallene longiceps. J Nat Hist 15:49–62

Nakamura K, Kano Y, Suzuki N, Namatame T, Kosaku A (2007) 18S rRNA phylogeny of sea spiders with emphasis on the position of Rhynchothoracidae. Mar Biol 153:213–223

Ohshima H (1933) Young pycnogonids found parasitic on nudibranchs. Annot Zool Jpn 14:61–66

Ohshima H (1937) The life-history of “Nymphonella tapetis” Ohshima (“Pantopoda, Eurycydidae”). Extr C R XII Congr Int Zool Lisb 1935:1616–1627

Okuda S (1940) Metamorphosis of a pycnogonid parasitic in a hydromedusa. J Fac Sci, Hokkaido Imperial Univ 7:73–86, Ser 6

Prpic NM, Damen WGM (2009) Notch-mediated segmentation of the appendages is a molecular phylotypic trait of the arthropods. Dev Biol 326:262–271

Regier JC, Shultz JW, Zwick A, Hussey A, Ball B, Wetzer R, Martin JW, Cunningham CW (2010) Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences. Nature 463:1079–1083

Rota-Stabelli O, Campbell L, Brinkmann H, Edgecombe GD, Longhorn SJ, Peterson KJ, Pisani D, Philippe H, Telford MJ (2011) A congruent solution to arthropod phylogeny: phylogenomics, microRNAs and morphology support monophyletic Mandibulata. Proc R Soc B 278:298–306

Salazar-Vallejo S, Stock JH (1987) Apparent parasitism of Sabella melanostigma (Polychaeta) by Ammothella spinifera (Pycnogonida) from the Gulf of California. Rev Biol Trop 35:269–275

Sanchez S (1959) Le développement des Pycnogonides et leurs affinités avec les Arachnides. Arch Zool Exp Gén 98:1–102

Scholtz G, Edgecombe GD (2006) The evolution of arthropod heads: reconciling morphological, developmental and palaeontological evidence. Dev Genes Evol 216:395–415

Sekiguchi K, Nakamura K, Onuma S (1971) Egg-carrying habit and embryonic development in a pycnogonid, Propallene longiceps. Zool Mag 80:137–139

Stock JH (1994) Indo-west pacific Pycnogonida collected by some major oceanographic expeditions. Beaufortia 44:17–77

Ungerer P, Scholtz G (2009) Cleavage and gastrulation in Pycnogonum litorale (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida): Morphological support for the Ecdysozoa? Zoomorphology 128:263–274

Vilpoux K, Waloszek D (2003) Larval development and morphogenesis of the sea spider Pycnogonum litorale (Ström, 1762) and the tagmosis of the body of Pantopoda. Arthropod Struct Dev 32:349–383

von Reumont BM, Meusemann K, Szucsich NU, Dell’Ampio E, Gowri-Shankar V, Bartel D, Simon S, Letsch HO, Stocsits RR, Luan Y, Wägele JW, Pass G, Hadrys H, Misof B (2009) Can comprehensive background knowledge be incorporated into substitution models to improve phylogenetic analyses? A case study on major arthropod relationships. BMC Evol Biol 9:119

Winter G (1980) Beiträge zur Morphologie und Embryologie des vorderen Körperabschnitts (Cephalosoma) der Pantopoda Gerstaecker, 1863. I. Entstehung und Struktur des Zentralnervensystems. Z Zool Syst Evol-Forsch 18:27–61

Zrzavý J, Hypsa V, Vlásková M (1997) Arthropod phylogeny: taxonomic congruence, total evidence and conditional combination approaches to morphological and molecular data sets. In: Fortey RA, Thomas RH (eds) Arthropod relationships. Chapman and Hall, London, pp 97–107

Acknowledgments

Karen Gowlett-Holmes and Mick Baron are thanked for sharing their knowledge of Tasmanian dive sites and their invaluable help in collecting Pseudopallene sp. The help of Paul Whitington, Roy Swain, Glenn Johnstone, and Jonny Stark with the logistics of organizing the essential chemicals for processing the developmental stages is greatly appreciated. David Staples kindly provided hatching larvae of Stylopallene cheilorhynchus and S. longicauda. We are grateful to Wilfried Bleiss and Gabriele Drescher for assistance with the scanning electron microscope. Ekaterina Ponomarenko is thanked for the translation of Russian literature.

Collection of animals and their offspring was made possible by permits of the Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (permit nos. 6039 and 9255). Export of collected material was permitted by the Australian Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (permit nos. WT2008-4394 and WT2009-4260). GB was in part supported by the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes and CPA was supported by Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS, grant 204-61). The project was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Scho 442/13-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Communicated by S. Roth

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

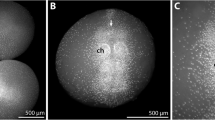

Supplementary Fig. 1

Walking leg articulation in PS 2 of Pseudopallene sp. Imaris volume, autofluorescent signal. a Walking leg 1, anterior view. The leg possesses the adult number of podomeres, the podomere borders being discernible as regions with higher signal intensity. b Walking leg 2, anterior view. The leg possesses only seven podomeres (including terminal claw), regions of future subdivisions in precursor podomeres are not yet assessable. Note high signal intensity in the cuticular fold relating to the anal opening (arrowhead). cx Coxa, fe femur, pro propodus, ta tarsus, tb tibia, tc terminal claw, wl walking leg (JPEG 57 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 2

Walking leg-bearing larvae of Stylopallene cheilorhynchus and Callipallene sp. SEM micrographs and nucleic stainings. a–c S. cheilorhynchus. a Freshly hatched PS 1, anterolateral view. Proboscis and chelifores of the specimen are still inserted in the ripped egg membrane (arrow) and probably an embryonic cuticle. The egg membrane is covered by a hardened sticky matrix via whose stalk-like projection (directed to the left) the egg remains attached to the father’s oviger. The unarticulated limb buds of walking leg 1 and 2 protrude freely from the egg membrane. b PS 1, ventral view. Note the folds of the walking leg tissue beneath the cuticle. c PS 1, posterior view. A tiny interior primordium of walking leg 3 is detectable in the hind body region. The proctodeum/anus is forming beneath the cuticle. The distalmost portion of walking leg 2 will most likely give rise to tarsus and propodus as well as the terminal claw. Proximal to this region, the differentiating tibia 2 may be discernible. d–f Callipallene sp. d Hatched and still attaching PS1, anterolateral view. Note the elongate anlagen of walking leg pairs 1–3. The arrow indicates a piece of ripped egg membrane (plus part of embryonic cuticle?) that still covers the proboscis and is still attached to the spinning gland of the chelifore. Presumptive podomere regions are labeled along walking leg 1. e PS 1, lateral view, Imaris volume (blend). The spinning gland process is distinctly visible due to its autofluorescent signal. A shallow elevation of the developing ocular tubercle lies slightly anterior to walking leg 1. Note the primordium of walking leg 4 as well as the interior tissue folds of walking legs 1–3 that may partially directly relate to the borders of future leg podomeres. f PS 1, ventral view. Walking leg pair 3 is bent in an anterior direction, being wedged between walking leg pairs 1 and 2. The primordium of walking leg pair 4 is already externally detectable, flanking the hind body region that still lacks an anus. ch chelifore, cx coxa, fe femur, ot ocular tubercle, pr proboscis, pro propodus, sgp spinning gland process, ta tarsus, tb tibia, tc terminal claw, wl walking leg (JPEG 124 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brenneis, G., Arango, C.P. & Scholtz, G. Morphogenesis of Pseudopallene sp. (Pycnogonida, Callipallenidae) II: postembryonic development. Dev Genes Evol 221, 329–350 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00427-011-0381-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00427-011-0381-5