Abstract

Equisetaceae has been of research interest for decades, as it is one of the oldest living plant families, and also due to its high accumulation of silica up to 25% dry wt. Aspects of silica deposition, its association with other biomolecules, as well as the chemical composition of the outer strengthening tissue still remain unclear. These questions were addressed by using high resolution (<1 μm) Confocal Raman microscopy. Two-dimensional spectral maps were acquired on cross sections of Equisetum hyemale and Raman images calculated by integrating over the intensity of characteristic spectral regions. This enabled direct visualization of differences in chemical composition and extraction of average spectra from defined regions for detailed analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and basis analysis (partial least square fit based on model spectra). Accumulation of silica was imaged in the knobs and in a thin layer below the cuticula. In the spectrum extracted from the knob region as main contributions, a broad band below 500 cm−1 attributed to amorphous silica, and a band at 976 cm−1 assigned to silanol groups, were found. From this, we concluded that these protrusions were almost pure amorphous, hydrated silica. No silanol group vibration was detected in the silicified epidermal layer below and association with pectin and hemicelluloses indicated. Pectin and hemicelluloses (glucomannan) were found in high levels in the epidermal layer and in a clearly distinguished outer part of the hypodermal sterome fibers. The inner part of the two-layered cells revealed as almost pure cellulose, oriented parallel along the fiber.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Equisetum hyemale is a hollow stemmed circumpolar distributed sphenopsid with highly reduced leaves. The pronounced jointed experience is characteristic for the Sphenopsida, in which Equisetum is the only surviving genus and thus of phylogenetic significance. Equisetum has a history stretching back to the Cretaceous and possibly as far back as the Triassic and may perhaps be the oldest living genus of vascular plants (Hauke 1978). The very specialized genus has been of research interest for decades (e.g. Tschudy 1939; Bierhorst 1958; Niklas 1989, 1997; Spatz et al. 1998), the “scouring rushes” (Equisetaceae) also because of their abnormal high accumulation of silica of up to 25% of dry weight (Timell 1964). In spite of the prominence of silicon as a mineral constituent of all terrestrial plants from 1% to several percent of the dry fraction, it is not counted among the elements defined as “essential”, except for members of the Equisetaceae (Epstein 1994). It was already shown in the seventies that in Equisetum, silica plays a role in the negative geotropic response (Srinivasan et al. 1979), and is essential for the growth (Chen and Lewin 1969) and completion of the life cycle (Hoffman and Hillson 1979). But although not essential for other monocots and dicots, beneficial effects like increased pest and pathogen resistance, drought and heavy metal tolerance and the quality and yield of agricultural crops have been recognized and thus the still unclear pathways and molecular mechanisms of silicon uptake and deposition have become of research interest (Adatia and Besford 1986; Raven 2003; Richmond and Sussman 2003; Ma 2004; Romero-Aranda et al. 2006). Silica is transported as monosilicic acid from the roots to the terminal regions via the transpiration stream and deposited as amorphous silica gel (SiO2·nH2O) in cell lumens, cell walls, and intercellular spaces or external layers (Hartley and Jones 1972; Raven 1983; Epstein 1994). The surface micromorphology and ultrastructural motifs of silica are observed to be complex (Perry and Fraser 1991) and new attempts to gain insights into the ultrastructure of the biogenic silica and to understand the function and process of biosilification have been undertaken, also in order to learn for the generation of new materials (Perry and Fraser 1991; Harrison 1996; Perry and Keeling-Tucker 2000; Dietrich et al. 2002; Holzhüter et al. 2003; Perry and Keeling-Tucker 2003; Valtchev et al. 2003). Besides the beneficial effects of silica on growth and against abiotic and biotic stresses, the idea of mechanical strengthening is also reported (Lewin and Reimann 1969; Kaufman et al. 1971, 1973; Raven 1983; Epstein 1999). For E. hyemale, minor importance of silica for the mechanical stability of the internodes was proposed and stiffness and strength was found to rely mainly on an outer ring of the strengthening tissue (Speck et al. 1998). The cells of the strengthening tissue in the outer cortex (hypodermal sterome) are uniformly thick-walled, vital and nonlignified and provide stiffness and strength in the longitudinal direction (Speck 1998). A knowledge gap exists on the molecular composition and structure of the mechanically important hypodermal sterome as well as on the silica deposition in context with other molecules in the different anatomical regions. These questions will be addressed in this paper using confocal Raman microscopy.

The combination of Raman and infrared spectroscopy with microscopy has evolved an important set of tools for plant research as information concerning the molecular structure and composition of plant tissue can be investigated in a close to native state and in context with structure (e.g. McCann et al. 1992, 2001; Séné et al. 1994; Morris et al. 2003; Gierlinger and Schwanninger 2007; Schulz and Baranska 2007). Both the methods are based on discrete vibrational transitions that take place in the ground electronic state of molecules. While Raman scattering involves excitation of a molecule by inelastic scattering with a photon (from a laser light source), infrared absorption spectroscopy typically involves photon absorption, with the molecule excited to a higher vibrational energy level (Schrader 1995). Raman scattering depends on changes in the polarizability of functional groups due to molecular vibration, while infrared absorption depends on changes in the intrinsic dipole moments induced by molecular vibrations. Therefore, Raman and infrared spectroscopy can provide “complementary” information about the molecular vibrations. Technical advances in laser and camera technique have put forward the chemical imaging and chemical mapping techniques in both the areas (Salzer et al. 2000; Chenery and Bowring 2003). Raman microspectroscopy has the advantage that spectra can be acquired on aqueous, thicker not opaque samples with a higher spatial resolution, but sample fluorescence may limit the quality of the spectra. The introduction of the NIR-FT-Raman technique led to many applications on green plant material by eliminating the problem of sample fluorescence. For mapping and imaging of whole plant organs (seeds, fruits, leaves) the lateral resolution (∼10 μm) of the NIR-FT technique is adequate and was already applied successfully on plant tissues e.g. (Himmelsbach et al. 1999; Baranska et al. 2004, 2006; Baranska and Schulz 2005). For investigations on the lower hierarchical level of cells and cell walls, the high resolution (<1 μm) gained with a visible laser based system is needed (Agarwal 2006; Gierlinger and Schwanninger 2006).

In this paper we demonstrate high resolution Raman imaging on a cross-section of E. hyemale with the aim to get new insights into silica deposition and association with other biopolymers as well as the composition and structure of the mechanically strengthening tissue.

Materials and methods

Shoots of scouring rush (E. hyemale) were derived from the Botanical Garden Drachenberg at the University of Potsdam, Germany. Stalks were harvested after 3 months of budding period. About 1 cm long samples from the second internode of the stalk were watered and embedded in polyethylenglycol (PEG1500). From the embedded blocks, 15-μm-thick cross sections were cut using a rotary microtome (Leica RM2255, Wetzlar, Germany), immediately placed on a glass slide and the water-soluble PEG removed by repeated washing. To avoid evaporation of water during the measurement, the sample was sealed after adding a drop of fresh water below a coverslip using nail polish.

Spectra were acquired with a confocal Raman microscope (CRM200, Witec, Ulm, Germany) equipped with a piezo-scanner (P-500, Physik Instrumente, Karlsruhe, Germany) and an objective from Nikon (60 NA = 0.8). A linear-polarized laser (diode pumped green laser, λ = 532 nm, CrystaLaser, Reno, NV, USA) was focused with a diffraction limited spot size (0.61λ/NA) and the Raman light was detected by an air-cooled, back illuminated spectroscopic CCD (Andor, Belfast, North Ireland) behind a grating (600 g mm−1) spectrograph (Acton, Princeton Instruments Inc., Trenton, NJ, USA) with a resolution of 6 cm−1. The laser power on the sample was approximately 5 mW. For the mapping, an integration time of 2 s and 0.66 μm steps were chosen and every pixel corresponds to one scan.

The ScanCtrlSpectroscopyPlus software (Witec) was used for measurement setup and image processing. Chemical images were achieved using a sum filter, integrating over defined wavenumber regions in the spectrum. The filter calculates the intensities within the chosen borders and the background is subtracted by taking the baseline from the first to the second border. The overview chemical images enabled us to separate regions differing in chemical composition and to mark by hand defined areas in order to calculate average spectra from these regions of interest for a detailed analysis. Spectra were extracted separately from the epidermal layer, from the cell corner and from the inner and outer part of the fiber. This was done on every image by marking four different cell corners (CC), the cell wall or separated cell wall layers of four single cells to get four representative average spectra per region and image. To exclude differences in intensity due to changed focus and sample height between the different separate scannings, the 36 spectra were normalized within the carbohydrate region (min/max from 1,197 to 1,023 cm−1) before being subjected to a principal component analysis (PCA) using the Unscrambler software package (version 9.1). The PCA (data mean centered, full cross validation) resolves sets of data into orthogonal components whose linear combinations approximate the original data to any desired degree of accuracy. So called principal components (PCs) are computed iteratively, in a way that the first PC carries the most explained variance and the second holds the maximum share of the residual information, and so on. Main results of PCA are variances (how much error is taken into account by the successive PCs), component loadings (how much a variable contributes to a PC) and scores (the sample location along a PC axis).

As plant cell walls consist of N different compounds, every acquired Raman spectrum is a linear superposition (S) of the spectra of the single compounds. If spectra of the specific compounds (basis spectra, B k) are known it is possible to estimate the weighting factor a k by the least squares fit (S = ∑a k B k). The weighting factor (a k) is proportional to the quantity of the component k in the material. The analysis was done using a “silica-spectrum” derived from the knob region, a “pectin spectrum” from the cell corner and a “cellulose/hemicellulose” spectrum from the fiber in the inner tissue part as basis spectra and thus model compounds. Each spectrum of the two-dimensional graph data object is fitted by a linear combination of the basis spectra using the least-squares method. The weighting factors are stored in an image and different coloring and combination of the images visualize the distribution of the different model compounds within one image.

To verify band assignment and our conclusions on the chemistry of E. hyemale, additional spectra were acquired from several model substances. The spectra and band assignment of model substances used for the data interpretation were (1) silica gel to verify the amorphous nature of silica, (2) a Ramie fiber of almost pure cellulose and microfibrils aligned parallel along the fiber (Edwards et al. 1997) measured perpendicular to the laser polarization to be compared with parallel alignment in cross sections, (3) konjac glucomannan (Megazyme) composed of d-glucose and d-mannose in the ratio of 2:3 and a relatively low degree of branching (Kato et al. 1973), and (4) the esterified pectin from citrus fruit (Sigma, P-9311) with the greatest similarity to the pectin bands found in horsetail tissue.

Results

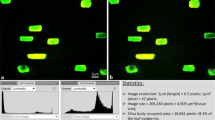

Figure 1 shows a picture of a 3-month-old stem of E. hyemale (a) and a light microscope overview of a cross section (b) with a zoom into the outer investigated part (c). The areas chosen for Raman scanning are marked by squares and include an epidermal region with a knob, the adjacent tissue in the hypodermal sterome as well as a map further inward towards the vascular bundle and an additional area beside the knob. After mapping the described areas, an average spectrum of the mapped region was calculated (Fig. 2a) and by integrating over the most intense Raman bands, first chemical images were calculated (Fig. 3a–c). The most prominent bands are found in the region between 2,796 and 3,068 cm−1, assigned to C–CH3, O–CH3 and CH2 stretching modes (Parry and Smithson 1957), between 1,002 and 1,199 cm−1, corresponding mainly to C–C ring breathing and C–O–C stretching vibrations of carbohydrates (Edwards et al. 1997; Kacuráková et al. 1999) (Table 1) and between 225 and 580 cm−1, known for contributions of amorphous silica (González et al. 2003). Integrating over these regions, gives three different chemical images (Fig. 3a–c). As CH-groups are present in various biomolecules, in the first image almost all structures are highlighted, but the knob less (Fig. 3a). Intensity increases from the knob border inwards and on the outer surface beside the knob, a cuticular wax layer can be distinguished. The C–O and C–O–C stretching regions (Fig. 3b) represent mainly cellulose and other carbohydrates. As the intensity vanishes completely in the knob region, we conclude that no carbohydrates or very small amounts are present in these appendences. The integration over the amorphous silica gives a contrary picture: high intensity and thus high silica content is observed in the knob and the concentration is diminishing inwards. For a detailed analysis, average spectra are derived from the regions marked in Fig. 3c along the detected silica gradient. The spectrum from the knob (Fig. 2b, spectrum 1) shows a remarkable broad band feature in the low wavenumber region, typical for amorphous silica (Dietrich et al. 2002). Besides a rather strong band is found at 973 cm−1, which is assigned to surface and internal silanol stretching, and a broader one at 802 cm−1 [Si–O–Si, Si–C stretching, (Gailliez-Degremont et al. 1997; Table 1)]. The similarity of the knob spectra with the below plotted silica gel spectrum is obvious and mainly differs in the additional organic contributions at 2,939 cm−1 and 1,460 cm−1. These two bands give hint to CH-groups, while the broad band at 1,658 cm−1 might indicate proteins (Séné et al. 1994). No cellulose and hemicelluloses are supposed to be associated with the silica as contributions in the C–O and CC region are weak and contributed by Si–O stretching, but a weak band at 858 cm−1 might indicate a very small amount of pectin. So the chemistry of the outer knob region can be described as almost pure amorphous silica gel probably associated with methoxy groups and small amounts of protein and pectin. A weak band at 1,297 cm−1 may also point to this association, as assigned to symmetric deformation of Si(CH3) (Gailliez-Degremont et al. 1997). Integrating over the silanol band at 976 cm−1 results in high intensity in the outer knob region with a border to the inner part (Fig. 3d), suggesting that the silica in the knob region is different from the silica in the adjacent epidermal layer. The average spectra from the inner parts (2,3) confirm the absence of the silanol groups at 976 cm−1, but show a weak band at 956 cm−1. The broad band below 500 cm−1 is decreasing and shows some bands e.g. at 440 and 349 cm−1, probably from carbohydrates. Although the carbohydrates contribute in this lower wavenumber region, the observed overall intensity is remarkable high and we suppose that silica is still present in these regions, but in much lower amount and in another form than in the knobs. Characteristic carbohydrate bands assigned to CH- stretching (around 2,900 cm−1) and bending (1,380, 1,324 cm−1) and C–O–C stretching (1,117, 1,090 cm−1) are observed (Wiley and Atalla 1987; Edwards et al. 1997). The bands between 860 and 520 cm−1 show a contribution of carbohydrates other than cellulose. The characteristic sharp band at 856 cm−1 can be seen as a marker band for α-glycosidic bonds in pectin (Synytsya et al. 2003; Fig. 2c) and is more pronounced in the inner part, together with another pectin deriving band at 685 cm−1. Integrating over the 859 cm−1 band confirms higher concentration of pectin inwards and a round cell wall structure comes out for the first time by this integration (Fig. 3e). Notable is also that the only cell visualized in the other images (Fig. 3a, marked with*) is now surrounded by a pectin-rich layer. On contrary, integrating over the closely neighbored bands at 892, 902 and 918 cm−1 (Fig. 3f), results in a similar picture like integration over the C–O and C–C region (Fig. 3b). The 902 cm−1 band can be attributed to cellulose (Wiley and Atalla 1987; Fig. 2c) or also to xylan-type polysaccharides (Kacuráková et al. 1999), whereas the 892 and the 918 cm−1 bands are not reported for cellulose, xylan-type hemicelluloses and glucomannan of wood (Agarwal and Ralph 1997). Measuring glucomannan from konjac (d-glucose and d-mannose in the ratio of 2:3) revealed a relatively strong contribution at 897 cm−1 with shoulders on both the sides (Fig. 2c). Therefore we suggest that this band feature derived from a galactoglucomannan (with a sugar ratio of 1:1:23 and thus almost a true mannan), which is reported to be found in high amounts (15%) in Equisetum (Timell 1964).

Overall average spectrum of the mapped knob region (a) and average spectra extracted from defined, selected regions: the knob area (1), below (2) and further inwards (3) (regions marked in the Raman image Fig. 3c) together with a spectrum acquired from silica gel (b). For comparison and verification of band positions, additionally the fingerprint region of three selected carbohydrate model spectra [Ramie fiber (cellulose), konjac glucomannan and esterified pectin from citrus fruit] are plotted (c)

Raman images (100 × 100 μm) of the knob region calculated by integrating from 2,796 to 3,068 cm−1 (a, all organics), 1,002–1,199 cm−1 (b, carbohydrates), 2,25–5,80 cm−1 (c, amorphous silica), 931–1,013 cm−1 (d, silanol groups of silica), 844–875 cm−1 (e, pectin) and 874–934 cm−1 (f, mainly hemicelluloses)

Raman images (60 × 60 μm) of the hypodermal sterome region calculated by integrating from 1,002 to 1,199 cm−1 (a, carbohydrates), very restricted wavenumber ranges from 2,931 to 2,819 cm−1 (b, accentuating cellulose oriented in fiber directon), 844–875 cm−1 (c, pectin) and 874–934 cm−1 (d, mainly hemicelluloses). Spectra were extracted from the cell corners (CC) the inner part of the hypodermal sterome fibers (FIB IN) and the outer part (FIB OUT)

Raman images (60 × 60 μm) of the inner tissue region connecting towards the vascular bundles calculated by integrating from 1,002 to 1,199 cm−1 (a, carbohydrates), very restricted wavenumber ranges from 2,931 to 2,819 cm−1 (b, accentuating cellulose oriented in fiber directon), 844–875 cm−1 (c, pectin) and 874–934 cm−1 (d, mainly hemicelluloses). Spectra were extracted from the cell corners (CC) and the fibers (FIB)

Raman images (100 × 100 μm) of the epidermis and hypodermal sterome at the groove region calculated by integrating from 225 to 580 cm−1 (a, amorphous silica), very restricted wavenumber range from 2,931 to 2,819 cm−1 (b, accentuation of cellulose oriented parallel to the fiber and cuticula), from 844 to 875 cm−1 (c, pectin) and from 874 to 934 cm−1 (d, mainly hemicelluloses). Spectra were extracted from the epidermal layer (EPI), the cell corners (CC) and the inner (FIB IN) and outer part (FIB OUT) part of the hypodermal sterome fibers

Two additional spectral mappings were done, moving further inwards into the hypodermal sterome and towards the vascular bundles (marked in Fig. 1 as Figs. 4 and 5). Silica mapping is not shown, since no significant contributions appeared in the silanol and below the 500 cm−1 region. In the first image (Fig. 4a, 1,002 cm−1 to 1,199 cm−1, carbohydrates), cell corners and middle lamella are not distinguished, but the circular fibers with channels of lower intensity between them become visible. If the integration is restricted to a small area, comprising the orientation sensitive CH2 stretching of cellulose at 2,902 cm−1 (Gierlinger and Schwanninger 2006), a two-layered structure of the hypodermal sterome cells comes out. By this integration, an inner layer with high intensity is separated from an outer layer; the cell corner (CC) and middle lamella are visualized by low intensity (Fig. 4b). Integration over the characteristic pectin band at 859 cm−1 shows the inverse picture: high intensity in the cell corners and diminishing from the outer part of the cell wall to almost not found in the inner part (Fig. 4c). Integration over the neighboring bands from 874 to 934 cm−1 shows similar high intensity in the cell corners and the outer part of the cell wall, but low intensity in a kind of connecting channels and the inner part of the hypodermal sterome cells (Fig. 4d). In the mapping, further inwards, intensity of all bands is diminished (Fig. 5a, b, d), except for the pectin band at the cell corner position (Fig. 5c). The two-layered structure is not found anymore: cellulose seems to be oriented parallel in respect to the fiber orientation (high intensity in Fig. 5b) and connected by a pectin-rich middle lamella and cell corners (Fig. 5c). The intensity of the hemicelluloses is very low in middle lamella as well as in the fibers (Fig. 5d).

Finally mapping was done for the epidermal layer and the hypodermal sterome in an outer region, where no knob is present, and there is no connection towards the vascular bundle (Fig. 6a–d). The Si-signal is rather weak compared to the knob region, but an increase in intensity is found in an outer layer below the cuticula (Fig. 6a). Restricting the cellulose wavenumber areas to the band at 2,902 cm−1 enhances again an inner layer, which becomes gradually thicker towards the inner part of the hypodermal sterome (Fig. 6b). Integration over the pectin band at 859 cm−1 shows high intensity in the epidermal layer and in the cell corners of the hypodermal sterome (Fig. 6c). Integration over the neighbored bands from 874 to 934 cm−1 shows again enhancement of the epidermal layer, but also the outer part of the cell walls in contrary to the inner cell wall (Fig. 6d).

Spectra for a detailed analysis, including principal component analysis (PCA), were extracted separately from the epidermal layer (Fig. 6c), from the cell corners (CC, Figs. 4c, 5c, 6c), the imaged inner and outer part of the round hypodermal sterome cells (Figs. 4b, 6b) and from the uniform fibers in the inner tissue part (Fig. 5b). The scores plot (Fig. 7a) of the PCA shows that the first two principal components (PC1, PC2), which explain 86 and 11% of the variance, separate into three groups (Fig. 7a). Within the groups, the four spectra derived per variant from single cells and cell corners fall close together, pointing to low variability from cell to cell and uniformity within the regions defined by the chemical imaging technique. The cell corner (CC) spectra of the inner tissue part (Fig. 5) are separated on the positive side from all others. This indicates a different chemical composition of the CC in the outer hypodermal sterome compared to the tissue towards the vascular bundle. The CC spectra of the outer hypodermal sterome (Figs. 4, 6) are chemically more similar to the epidermal layer as well as to the outer part of the fibers, and group along the PC1 axes in the middle (Fig. 7a, group 2). Spectra of the outer fiber parts of the two different mappings (Figs. 4, 6) fall close together (group 2) as well as the ones derived from the inner part (group 3), confirming again differences in chemistry and structure within the layered hypodermal sterome fibers. The spectra of the inner fiber part of the two different mappings are grouped together with the spectra of the uniform fibers of the inner tissue part on the negative side of PC1 (Fig. 7a, group 3). The corresponding loading of PC1 (Fig. 7b, black line) shows that the main explained variance arises from differences in pectin assigned bands at 856, 685, 448, 1,078, 1,413 and 1,323 cm−1 (Table 1, Fig. 2c). This means that the CCs derived from Fig. 5 are richer in pectin than all other variants. Within group 2, the pectin content decreases from the CC of the outer tissue parts to the epidermal layer to the outer parts of the fibers and is diminished in group 3, which is separated on the negative side (Fig. 7a) The second principal component (PC2) separates the group in the middle (2) from the other two groups (Fig. 7a). The loading of PC2 (Fig. 7b, grey line) shows that this variance arises from negative bands at 1,082, 918, 888, 1,256 cm−1and on the positive side at 497 and 379 cm−1. A comparison with the model spectra (Fig. 2c) supports the idea that these negative bands reflect mainly a change in hemicellulose (glucomannan) content, whereas the two positive ones at 497 and 379 cm−1 correspond to cellulose (Fig. 2c). A grouping of the spectra according to the results of the PCA gives a detailed view on the chemical differences along the tissues and cell wall layers (Fig. 7c). The bands at 916, 890 and 1,257 cm−1 are typically found within the second group (Fig. 7c, spectra 2) and confirm the results of the second loading and conclusion on similar high hemicellulose content within this group. In contrast, pectin bands (e.g. 856, 1,325 and 1,413 cm−1 marked with arrows) show small changes of the pectin content within this group (more in the CC than in the outer fiber parts). The band intensities and positions of the CC spectrum of the inner part (1) fit well with that ones found for esterified pectin of citrus fruit (Fig. 2c) and we propose that this spectrum represents almost pure pectin. The band position of the 856 cm−1 band is sensitive to modification of the C-6 carboxyl (Synytsya et al. 2003), but is not changed significantly between the different spectra (group 2 and 1). In the normalized carbohydrate region, the band shape and positions change between the three groups from a broad more typical pectin band with maxima at 1,103 and 1,081 cm−1 (1) to a more sharp band feature with typical maxima of cellulose at 1,120 and 1,096 cm−1 in the fiber spectra (3). In the group 3 spectra, mainly cellulose bands are assigned and the similarity to the perpendicular oriented ramie fiber spectrum (Fig. 2c) suggests that the cellulose is oriented parallel along the fiber with a very low microfibril angle. The glucomannan bands are very low and and the pectin bands not found (Fig. 7c). Although carboxyl and acetyl groups give a weak Raman signal, a small, broad band is found around 1,732 cm−1 in all spectra, pointing to minor amounts of hemicelluloses with ester groups at all positions. In the spectrum with high pectin content (1) the band is shifted to 1,742 cm−1 by acetyl contributions from pectin.

Score plot (a) and loadings (b) of the principal component analysis (PCA) of spectra extracted from the cell corners (CC; Figs. 4c, 5c, 6c), epidermis (epi; Fig. 6c), the inner and outer fiber part (fib in, fib out; Figs. 4b, 6b) and the uniform fiber (Fig. 5b). Spectra were derived always from four individual cell corners and cells per image. The first principal component (PC1) explains 86% of the variance and corresponds according the loading (b, black line) mainly to pectin, whereas PC2 explains another 11% and reflects changes in hemicellulose composition and content (b, grey line). For details the fingerprint region of the normalised average spectra is shown (c), grouped (1–3) according the results in the score plot (a)

Since comparison with the model spectra (Fig. 2c) confirms that spectrum 1 and 3 (Fig. 7c) represent almost pure cellulose and pectin, respectively, these two were used together with the silica spectrum of the knob (Fig. 2b, spectrum 1) to fit the spectra of all mappings. By this, the distribution of cellulose, pectin and silica, respectively, are imaged and combined into one picture to summarize the results (8a-d). Silica accumulation is colored blue and confirmed in the knob region (Fig. 8a) as well as in a small layer below the cuticula in the region beside the knob (Fig. 8d). It becomes evident that silica is still present in the epidermal layer below the knob, in combination with cellulose/hemicellulose, whereas the pectin amount seems to be minor (Fig. 8a, pink color). Contrary, in the epidermal layer beside the knob, pectin content is high (Fig. 8d, green). While in the epidermis only a small cellulose/hemicellulose-rich inner ring (red) is found, it becomes continuously thicker inwards and the pectin becomes more and more restricted to the cell corners (Fig. 8d). Within the hypodermal sterome, the two-layered structure, with a pectinized outer ring and an inner ring with highly oriented cellulose is visualized once again (Fig. 8b). Further inwards, uniform pure cellulose/hemicellulose fibers are found and the pectin is restricted as usual to the CC and middle lamella (Fig. 8c).

Combined colour images (a–d) of all mapped regions (overview in Fig. 1, Raman images Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6) derived from a basis analysis (partial least square fit) with extracted, baseline corrected average spectra (e) representing mainly amorphous silica (extracted from Fig. 3c, area 1), pectin (Fig. 5c, cell corner) and cellulose (Fig. 5c, fiber). Blue represents high weighting factor and consequently content for silica, green for pectin and red for cellulose. The white color shows the cuticular layer and deposits within some lumens of the cells not further investigated

Discussion

Raman imaging and single spectra

The absence of lignin in the outer tissue parts of E. hyemale enabled to acquire Raman spectra at 532 nm excitation without fluorescence and consequently very good signal-to-noise ratio. The approach of Raman mapping and chemical imaging by integrating over the selected wavenumber region showed the potential of detecting differences in chemical composition in context with structure and with high spatial resolution. Without mapping it would be difficult or even impossible to localize the laser spot exactly on positions of interest, which are often not even visible from the light microscopic image or are not recognized as important before. Due to the sharp band at 858 cm−1, change in pectin content was successfully imaged, whereas cellulose and hemicelluloses were difficult to be separated due to strongly overlapping bands. Nevertheless, the integration from 874 to 934 cm−1 is supposed to represent the distribution of a special mannan, because a model spectrum of konjac glucomannan showed increased contribution within this region (Fig. 2c). The ester band (1,736 cm−1) allows in principle separating xyloglucan from cellulose, however for reliable imaging the band is too weak and contributions from pectin can interfere. The silica mapping revealed successfully the large difference between the knob and the regions below. However, low silica concentrations cannot easily be seen with the imaging technique as the main band of amorphous silica below 500 cm−1 is very broad and overlaps with several carbohydrate bands. The imaging technique is already a powerful tool as a first step in the analysis, but careful examination of the spectra and the extraction of average spectra from defined regions enhance the power of this technique. The final detailed overall analysis of the spectra gave additional insights into silica chemistry and deposition as well as the composition of the hypodermal sterome.

Silica distribution and chemistry

Chemical analysis revealed that silica is accumulated in horsetail in amounts of up to 25% (Timell 1964; Lewin and Reimann 1969). Studies using electron microprobe and transmission and scanning electron microscopy gave information on the distribution of silica in individual cells of the epidermis (Kaufman et al. 1971, 1973; Page 1972). Contrary to many other plants, silica in E. hyemale is mainly deposited in the outer epidermal cell walls, primarily in discrete knobs and rosettes and sometimes in a uniform pattern on and in the outer epidermal cell walls (Kaufman et al. 1971; Holzhüter et al. 2003). Our Raman studies confirm a small more silicified layer (<5 μm) below a cuticular wax layer (Figs. 6a, 8d). Nevertheless the highest silica accumulation was found at the ridges (Figs. 3b, 8a) in two isoforms: (1) in the knobs as almost pure amorphous, hydrated silica associated with methoxyl groups and small contributions of protein and pectin (Fig. 2b, spectrum 1) and (2) in the underlying radially enlarged epidermal cells accompanied by cellulose and hemicellulose and minor pectin (Fig. 2b, spectrum 2). On contrary, in the epidermal cells beside the knobs, very high pectin content is found (Fig. 6c). The low pectin and high silica content in the epidermal cells below the knob and their radial enlargement towards the knob suggest a kind of “dilution” of the pectin by the silica deposition. The occurrence of methoxy groups and spurious pectin within the highly silicified knobs also support the idea of a role of pectin in silica transport and/or deposition. Silicon is uptaken as silicic acid from the soil and transported in the transpiration stream via the water conducting xylem (Epstein 1994). However, the xylem pathway is not connected directly to the places of deposition and thus the further liquid-phase pathway has to be apoplastic. It is likely that the silicic acid can move to the final destinations easier in and with pectic acid or pectin rather than in cellulose–hemicellulose network. A bound form of silica to pectin was reported (Schwarz 1973), although not in Equisetum. Perry and Fraser (1991) found no silica in the middle lamella and thus concluded that silica in the cell walls of Euisetum arvense is not complexed or associated with the pectic cell wall polysaccharides that are prominent in the middle lamella. Nevertheless in E. hyemale the Raman study shows that pectin is not restricted to the middle lamella and quite high in the epidermal layer as well as the outer layer of the hypodermal fibers. Model silica precipitation studies using low and high molecular weight polymers of glucose and hemicellulosic extracts have shown that they have no discernible effect on the initial stages of silicic acid polycondensation, but they do influence particle growth and aggregations. It was suggested that carbohydrates might act in conjunction with other chemical species, such as intra-silica proteinaceous material, to control biosilification in higher plants. (Perry and Yun 1992; Harrison 1996; Perry and Keeling-Tucker 2000, 2003).

The spectral proof of bonding between silica and carbohydrates is difficult to find as organosilicon compounds give similar bands to those of the corresponding organic compounds (Sokrates 2001), which arise from the carbohydrates and may overlay the signals. Nevertheless, the fact that almost no silanol vibration is observed within the cell wall regions and a band arises nearby at 956 cm−1 (also seen as a shoulder in the knob spectrum) indicates a covalent bonding to carbohydrates (SiOC). But due to the uncertainty of the chemistry and spectra of the pectic and hemicelluloses in this plant their spectral contribution cannot yet be completely excluded. The increasing amounts of pectin and hemicelluloses in the outer parts, suggest more probably a close association of silica to pectin and hemicelluloses than to cellulose, which was found to be more restricted to the inner fiber parts. Investigations at different developmental stages might give further insights into the silica deposition.

Structure and chemistry of the hypodermal sterome

In Equisetum differentiation of the tissues proceeds in each articulation from above to downwards (Browne 1939). Therefore the cells just below the nodes used for this investigation are in a more mature condition. At this level, the tip of the projecting tooth of fibers under a rib can be connected with the bundle on the same radius by a single chainlike row of somewhat radially elongated cells with slightly thickened walls (Browne 1939), which were also investigated (Fig. 5a–d). These fibers showed uniform cell wall composition of highly oriented cellulose connected by pectin, which was found almost in pure form in the cell corners and middle lamella (Figs. 8d, 7c). Moving towards the hypodermal sterome, a similar composition and structure were only observed for the inner part of the fibers and a separate layer rich in pectin and hemicellulose was found to encompass the fiber, which continuously increased towards the epidermis (Fig. 8b, d). In an early chemical study on the whole tissue, large amounts of pectin were reported in Equisetum besides high amounts of a special galactoglucomannan (1:1:23), so far not found in the vascular tissue of any other plant (Timell 1964). From the Raman study, we conclude that this hemicellulose is restricted mainly to the outer part of the tissue and builds up together with pectin, a special layer around an inner cellulose/xyloglucan part. The cell wall structure of the inner fiber part (highly oriented cellulose associated with xyloglucan and almost no pectin) seems to reflect more secondary cell wall character and can provide the tensile stiffness in the longitudinal direction. E. hyemale shows a pronounced biphasic stress–strain relation in tension and viscoelasticity, particularly for large strains (Speck et al. 1998). This behavior could not be interpreted on the ultrastructural or molecular level (Speck et al. 1998), but might now be explained by contribution of the outer hemicelluloses–pectin-rich layer. Besides the high pectin/hemicelluloses content in the outer layer and epidermis might have essential function in the water relation and as discussed above in context with silica distribution and deposition.

Conclusion

Within the hypodermal sterome of E. hyemale, a two layered structure was visualized: higher amount of pectin and hemicelluloses (galactoglucomannan) were found in an outer ring confining an almost pure cellulose part with the cellulose microfibrils aligned parallel along the fiber. The outer layer gradually decreases towards the inner tissue part and the remarkable higher amount of pectin and hemicelluloses in the outer parts is proposed to play a role in silica deposition. Besides, in the epidermal layer and hypodermal sterome no silanol groups were detected, pointing to other bondings with pectin and hemicelluloses. In the knob region, spectra revealed almost pure, hydrated amorphous silica. Future studies in context with growth and development will give further insights into silicon biochemistry in plants.

Our results show the potential of scanning Raman microscopy for non-destructive in situ investigation of plant cell walls. The high spatial resolution allows detection of changes in the chemical composition of the cell and cell wall. Conclusions about all components can be derived at once and in context with structure. This major advantage and potential also comprises a drawback as highly overlapping bands are sometimes difficult to interpret and conclusions on components with minor amount may be ambiguous. Nevertheless, experiments on other cell wall variants and selective chemical treatment will improve our understanding of the spectra as well as the combination with other methods (e.g. antibody probes).

Abbreviations

- CC:

-

Cell corner

- EPI:

-

Epidermal layer

- FIB:

-

Fiber

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- PC:

-

Principal component

References

Adatia MH, Besford RT (1986) The effects of silicon on cucumber plants grown in recirculating nutrient solution. Ann Bot 58:343–351

Agarwal UP (2006) Raman imaging to investigate ultrastructure and composition of plant cell walls: distribution of lignin and cellulose in black spruce wood (Picea mariana). Planta 224:1141–1153

Agarwal UP, Ralph SA (1997) FT-Raman spectroscopy of wood: Identifying contributions of lignin and carbohydrate polymers in the spectrum of black spruce (Picea mariana). Appl Spectrosc 51:1648–1655

Baranska M, Schulz H (2005) Spatial tissue distribution of polyacetylenes in carrot root. Analyst 130:855–859

Baranska M, Schulz H, Rosch P, Strehle MA, Popp J (2004) Identification of secondary metabolites in medicinal and spice plants by NIR-FT-Raman microspectroscopic mapping. Analyst 129:926–930

Baranska M, Baranski R, Schulz H, Nothnagel T (2006) Tissue-specific accumulation of carotenoids in carrot roots. Planta 224:1028–1037

Bierhorst DW (1958) Vessels in Equisetum. Am J Bot 45:534–537

Browne IMP (1939) Anatomy of the aerial axes of Equisetum kansanum. Bot Gaz 101:35–50

Chen CH, Lewin J (1969) Silicon as a nutrient element for Equisetum arvense. Can J Bot 47:125–131

Chenery D, Bowring H (2003) Infrared and Raman spectroscopic imaging in bioscience. Spectrosc Eur 15:8–14

Dietrich D, Hemeltjen S, Meyer N, Baucker E, Ruhle G, Wienhaus O, Marx G (2002) A new attempt to study biomineralised silica bodies in Dactylis glomerata L. Anal Bioanal Chem 374:749–752

Edwards HGM, Farwell DW, Webster D (1997) FT Raman microscopy of untreated natural plant fibres. Spectrochim Acta A 53:2383–2392

Epstein E (1994) The anomaly of silicon in plant biology. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 91:11–17

Epstein E (1999) Silicon. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50:641–664

Gailliez-Degremont E, Bacquet M, Laureyns J, Morcellet M (1997) Polyamines adsorbed onto silica gel: a Raman microprobe analysis. J Appl Polym Sci 65:871–882

Gierlinger N, Schwanninger M (2006) Chemical imaging of poplar wood cell walls by confocal Raman microscopy. Plant Physiol 140:1246–1254

Gierlinger N, Schwanninger M (2007) The potential of Raman microscopy and Raman imaging in plant research—review. Spectroscopy 21:69–89

González P, Serra J, Liste S, Chiussi S, León B, Pérez-Amor M (2003) Raman spectroscopic study of bioactive silica based glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids 320:92–99

Harrison CC (1996) Evidence for intramineral macromolecules containing protein from plant silicas. Phytochemistry 41:37–42

Hartley RD, Jones LHP (1972) Silicon compounds in xylem exudates of plants. J Exp Bot 23:637–640

Hauke RL (1978) Taxonomic monograph of Equisetum subgenus Equisetum. Nova Hedwigia 30:385–455

Himmelsbach DS, Khahili S, Akin DE (1999) Near-infrared–Fourier-transform–Raman microspectroscopic imaging of flax stems. Vib Spectrosc 19:361–367

Hoffman FM, Hillson CJ (1979) Effects of silicon on the life-cycle of Equisetum hyemale L. Bot Gaz 140:127–132

Holzhüter G, Narayanan K, Gerber T (2003) Structure of silica in Equisetum arvense. Anal Bioanal Chem 376:512–517

Kacuráková M, Wellner N, Ebringerova A, Hromádková Z, Wilson RH, Belton PS (1999) Characterisation of xylan-type polysaccharides and associated cell wall components by FT-IR and FT-Raman spectroscopies. Food Hydrocolloid 13:35–41

Kato K, Kawaguchi Y, Mizuno T (1973) Structural analysis of suisen glucomannan. Carbohydr Res 29:469–476

Kaufman PB, Bigelow WC, Schmid R, Ghosheh NS (1971) Electron microprobe analysis of silica in epidermal cells of Equisetum. Am J Bot 58:309–316

Kaufman PB, Lacroix JD, Dayanand.P, Allard LF, Rosen JJ, Bigelow WC (1973) Silicification of developing internodes in perennial scouring rush (Equisetum hyemale Var Affine). Dev Biol 31:124–135

Lewin J, Reimann BEF (1969) Silicon and plant growth. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 20:289–304

Ma JF (2004) Role of silicon in enhancing the resistance of plants to biotic and abiotic stresses. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 50:11–18

McCann MC, Hammouri M, Wilson RH, Belton P, Roberts K (1992) Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy is a new way to look at plant cell walls. Plant Physiol 100:1940–1947

McCann MC, Bush M, Milionia D, Sadoa P, Stacey NJ, Catchpole G, Defernez M, Carpita NC, Hoft H, Ulvskov P, Wilson RH, Roberts K (2001) Approaches to understanding the functional architecture of the plant cell wall. Phytochemistry 57:811–821

Morris VJ, Ring SG, MacDougall AJ, Wilson RH (2003) Biophysical characterisation of plant cell walls. In: Rose J (ed) The plant cell wall—Annual plant reviews. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 55–91

Niklas KJ (1989) Safety factors in vertical stems—evidence from Equisetum hyemale. Evolution 43:1625–1636

Niklas KJ (1997) Relative resistance of hollow, septate internodes to twisting and bending. Ann Bot 80:275–287

Page CN (1972) Assessment of interspecific relationships in Equisetum Subgenus Equisetum. New Phytol 71:355–369

Parry DW, Smithson F (1957) Detection of opaline silica in grass leaves. Nature 179:975–976

Perry CC, Fraser MA (1991) Silica deposition and ultrastructure in the cell wall of Equisetum arvense—the importance of cell wall structures and flow control in biosilicification? PhilTrans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 334:149–157

Perry CC, Keeling-Tucker T (2000) Biosilicification: the role of the organic matrix in structure control. J Biol Inorg Chem 5:537–550

Perry CC, Keeling-Tucker T (2003) Model studies of colloidal silica precipitation using biosilica extracts from Equisetum telmateia. Colloid Polym Sci 281:652–664

Perry CC, Yun L (1992) Preparation of silicas from silicon complexes–role of cellulose in polymerization and aggregation control. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans 88:2915–2921

Raven JA (1983) The transport and function of silicon in plants. Biol Rev 58:179–207

Raven JA (2003) Cycling silicon—the role of accumulation in plants— Commentary. New Phytol 158:419–421

Richmond KE, Sussman M (2003) Got silicon? The non-essential beneficial plant nutrient. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6:268–272

Romero-Aranda MR, Jurado O, Cuartero J (2006) Silicon alleviates the deleterious salt effect on tomato plant growth by improving plant water status. J Plant Physiol 163:847–855

Salzer R, Steiner G, Mantsch HH, Mansfield J, Lewis EN (2000) Infrared and Raman imaging of biological and biomimetic samples. Fresenius J Anal Chem 366:712–726

Schrader B (1995) Infrared and Raman spectroscopy. VCH, Weinheim, 786 pp

Schulz H, Baranska M (2007) Identification and quantification of valuable plant substances by IR and Raman spectroscopy. Vib Spectrosc 43:13–25

Schwarz K (1973) Bound form of silicon in glycosaminoglycans and polyuronides - (polysaccharide matrix connective tissue). Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 70:1608–1612

Séné CFB, McCann MC, Wilson RH, Crinter R (1994) Fourier-transform raman and fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. An investigation of five higher plant cell walls and their components. Plant Physiol 106:1623–1631

Sokrates G (2001) Infrared and Raman characteristic group frequencies. Wiley, Chichester

Spatz H-C, Köhler L, Speck T (1998) Biomechanics and functional anatomy of hollow-stemmd sphenopsids. I. Equisetum giganteum (Equisetaceae). Am J Bot 85:305–314

Speck T, Speck O, Emanns A, Spatz HC (1998) Biomechanics and functional anatomy of hollow stemmed sphenopsids: III. Equisetum hyemale. Bot Acta 111:366–376

Srinivasan J, Dayanandan P, Kaufman PB (1979) Silica distribution in Equisetum hyemale var affine L (Engelm) in relation to the negative geotropic response. New Phytol 83:623–626

Synytsya A, Copikova J, Matejka P, Machovic V (2003) Fourier transform Raman and infrared spectroscopy of pectins. Carbohydr Polym 54:97–106

Timell TE (1964) Studies on some ancient plants. Sven Papperstidn 67:356–363

Tschudy RH (1939) The significance of certain abnormalities in Equisetum. Am J Bot 26:744–749

Valtchev V, Smaihi M, Faust AC, Vidal L (2003) Biomineral-silica-induced zeolitization of Equisetum arvense. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 42:2782–2785

Wiley JH, Atalla RH (1987) Band assignment in the Raman spectra of celluloses. Carbohydr Res 160:113–129

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Nöske (Potsdam University, Department of Chemistry) for providing the horsetail sample and I. Burgert and P. Fratzl (Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces, Department Biomaterials, Potsdam) for enabling the work and fruitful discussion. We acknowledge financial support from the Max Planck Society and the first author (N.G.) acknowledges the APART programme of the Austrian Academy of Sciences for financial support. We thank M. Schwanninger (BOKU, Vienna) for enabling the analysis with “The UNSCRAMBLER” software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gierlinger, N., Sapei, L. & Paris, O. Insights into the chemical composition of Equisetum hyemale by high resolution Raman imaging. Planta 227, 969–980 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-007-0671-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-007-0671-3