Abstract

As a contribution to the discussion about the possible effects of ethnicity/ancestry on age estimation based on DNA methylation (DNAm) patterns, we directly compared age-associated DNAm in German and Japanese donors in one laboratory under identical conditions. DNAm was analyzed by pyrosequencing for 22 CpG sites (CpGs) in the genes PDE4C, RPA2, ELOVL2, DDO, and EDARADD in buccal mucosa samples from German and Japanese donors (N = 368 and N = 89, respectively).

Twenty of these CpGs revealed a very high correlation with age and were subsequently tested for differences between German and Japanese donors aged between 10 and 65 years (N = 287 and N = 83, respectively). ANCOVA was performed by testing the Japanese samples against age- and sex-matched German subsamples (N = 83 each; extracted 500 times from the German total sample). The median p values suggest a strong evidence for significant differences (p < 0.05) at least for two CpGs (EDARADD, CpG 2, and PDE4C, CpG 2) and no differences for 11 CpGs (p > 0.3).

Age prediction models based on DNAm data from all 20 CpGs from German training data did not reveal relevant differences between the Japanese test samples and German subsamples. Obviously, the high number of included “robust CpGs” prevented relevant effects of differences in DNAm at two CpGs.

Nevertheless, the presented data demonstrates the need for further research regarding the impact of confounding factors on DNAm in the context of ethnicity/ancestry to ensure a high quality of age estimation. One approach may be the search for “robust” CpG markers—which requires the targeted investigation of different populations, at best by collaborative research with coordinated research strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Epigenetic age estimation based on DNA methylation (DNAm) holds the perspective of various forensic applications, e.g., for age estimation in persons without valid identity documents, the identification of unknown deceased, or the identification of the donor of a trace. Many models for the estimation of chronological age based on DNA methylation have been proposed [1,2,3,4]; the best of them enabling age estimation with mean absolute errors (MAE) of approximately 3–5 years [5,6,7,8].

However, there is a growing perception that DNA methylation may be influenced by exogenous and endogenous factors (for review, see [9,10,11]) that may be of relevance for age estimation based on DNAm. Against this background, Spolnicka et al. [12] claimed that “studies aiming to identify all potential players influencing differences in DNA methylation at particular loci between individuals at the same chronological age are important […] for better accuracy of age prediction models.”

In this context, the question of population-related differences in DNAm patterns and their impact on forensic age estimation has already been addressed [13,14,15]. Such differences may be even present at birth [16]. An association between DNAm, histone modifications, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) located at specific CpG sites (CpGs) has been interpreted as evidence for the genetic control of DNA methylation [17, 18]. Since SNP allele frequencies may differ considerably among populations of different ancestries, population-related differences in DNAm have been attributed to differences in population-specific alleles or haplotypes [19,20,21]. Apart from such genetic factors, lifestyle and environmental factors may alter the DNAm pattern. There is strong evidence for such influences from many studies (for review, see [11, 22, 23]). Although the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood, there is evidence that genetic variations as well as living conditions (both addressed as “ethnicity/ancestry” in the following) may impact DNAm levels and induce population-related differences [11, 22,23,24].

Such differences in age-associated DNAm changes between different populations have been described [20, 24,25,26,27], and their impact on forensic age estimation based on DNAm has already been discussed [13,14,15]. Some of these studies were based on the comparison of available Illumina BeadChip datasets of different groups, which may have batch effects that hamper a reliable comparison [24]. In several studies, already developed models were applied by other laboratories to another population, meaning that the samples of the two populations were analyzed in different labs [13, 14]. However, this approach cannot distinguish between methodological and actual population-related differences.

To gain further insight into the relevance of different populations for targeted epigenetic age predictors, DNAm was analyzed by pyrosequencing for 22 CpGs of five genes (PDE4C, RPA2, ELOVL2, DDO, and EDARADD) in buccal mucosa samples from German and Japanese donors, applying an identical methodological protocol by only one laboratory.

Material and methods

Sample collection

Buccal mucosa samples were collected from 368 German donors (203 females, 165 males; ages between 1 month and 94 years) from Germany, mainly from North Rhine-Westphalia and from 89 Japanese donors (55 females, 34 males; ages between 8 and 87 years) after written consent. Twelve of the Japanese donors had been living in Düsseldorf/Germany for several years at the time of sampling. The majority of the remaining 77 Japanese samples were taken in Fukuoka Prefecture (N = 59), the rest of the samples came from donors living in Ehime (N = 9), Shizuoka (N = 5), and Miyazaki (N = 3) Prefectures, respectively. For one sample, the exact sampling location was unknown.

DNA extraction, quantification, and bisulfite conversion

Genomic DNA from buccal swab samples of both groups was extracted using the NucleoSpin® Tissue Kit from Macherey–Nagel (Düren/Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with overnight lysis at 56 °C. DNA was eluted in 100 µl BE buffer (as part of the extraction kit) and DNA extracts were stored at − 20 °C until further analysis. Quantitation was performed following manufacturer’s instructions using either the Applied Biosystems™ 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Waltham, Massachusetts/USA) and the Quantiplex® ProKit (Qiagen, Hilden/Germany) or the QuantiFluor dsDNA Sample Kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin/USA) and Quantus Fluorometer (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin/USA).

Bisulfite conversion was performed using either the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold™ Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, California/USA) or the EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen, Hilden/Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. If possible, the recommended amount of 200 ng to 500 ng input DNA was used but not less than 10 ng per reaction volume (as recommended in [28]).

DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing (CpGs located in the genes PDE4C, RPA2, ELOVL2, DDO, and EDARADD)

Prior pyrosequencing marker-specific PCRs were performed either using the HotStarTaq Kit (Qiagen, Hilden/Germany) or the PyroMark PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden/Germany) under manufacturer’s conditions. Primer sequences were taken from the original papers [29,30,31]. Hereafter, 10–20 µl of biotinylated PCR product was immobilized to 1 μl Streptavidin Sepharose™HP beads (GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois/USA). Sequencing primers were designed as described previously [29,30,31]. Pyrosequencing was performed using the PyroMark Q24 Advanced CpG Reagents Kit (Qiagen, Hilden/Germany) and the PyroMark Q24 Advanced System (Qiagen, Hilden/Germany).

Testing for differences between DNAm in German and Japanese samples

In both donor groups, the relationship between DNAm and chronological age was analyzed by linear regression. For all CpGs (located in the genes PDE4C, RPA2, ELOVL2, EDARADD, and DDO), Spearman correlation coefficients (R) were calculated.

Due to the low number of Japanese individuals younger than 10 years and older than 65 years, only German and Japanese individuals with ages between 10 and 65 years (N = 287, N = 83, respectively) were included in all further analyses.

ANCOVA was performed to detect differences between the DNAm levels in the two populations; at a p value < 0.05, the results were considered significant. To further address the effects of different samples sizes and compositions, ANCOVA was performed by testing the Japanese sample (N = 83) against age- and sex-matched (all p > 0.3) German subsamples (N = 83 each) that were extracted 500 times from the total German group. The medians of these 500 runs were calculated.

Age estimation based on German training data: modeling

Modeling was based only on the data of individuals with ages between 10 and 65 years and on all CpGs except for ELOVL2, CpG 7, and DDO, CpG 1 (exhibiting the weakest correlations between DNAm and age with R < 0.75).

Age prediction models were trained using a random forest algorithm with (chronological) age as the continuous target variable as well as the 20 CpG information and sex as features for prediction. The prediction forest consisted of 10.000 individual trees that were built from bootstrap samples of the entire dataset using the curvature test. This test selected the split predictor that minimizes the p value of chi-square tests of independence between each predictor, i.e., feature, and the response, i.e., age.

Modeling was based on training data consisting of the data of the German donors under the exclusion of extracted German test samples (see below), resulting in a strict separation between training and test data. The performance of the models was tested (a) in the Japanese sample (N = 83; Japanese test sample) and (b) in age- and sex-matched (all p > 0.3) German subsamples (N = 83 each).

Age estimation based on German training data: performance on the Japanese sample and on age- and sex-matched German test samples

As a measure of prediction accuracy, the mean absolute errors (MAE) were calculated. The performance of age estimation based on the German training data was tested in the Japanese sample (Japanese test sample) and in age- and sex-matched German test samples, respectively. To minimize sampling effects, we did not rely on randomizing the German data into one training and one test set but extracted 83 German test samples 500 times from the total German sample. The 83 German test samples and the 83 Japanese samples were age- and sex-matched, each. Means and medians of the resulting 500 MAEs were calculated for each group.

To detect biases with the consequence of systematic over- or underestimation, the mean deviation of the age gaps (the differences between estimated and chronological ages) was calculated for all 500 runs; the means and medians of the resulting 500 mean deviations were calculated in each group.

Results

Buccal swabs from German and Japanese donors: very similar correlation between DNAm levels and age but evidence for significant differences in DNAm at least at two CpG sites

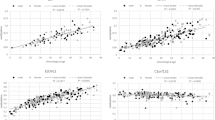

Analysis of the German and Japanese samples revealed age-associated DNAm levels and a mostly close correlation between DNAm and age in both donor groups, with similar correlation coefficients (Spearman R) between 0.95 (PDE4C, CpG1) and 0.67 (ELOVL2, CpG 7) in Germans and between 0.93 (PDE4C, CpG 1) and—0.62 (DDO, CpG 1) in Japanese, respectively (Table 1). In both donor groups, DNAm levels increase at the CpGs of ELOVL2, PDE4C, and RPA2 and decrease at EDARADD and DDO with increasing age (data for DDO and the CpGs of ELOVL2, PDE4C, EDARADD, and RPA2 with the highest correlations between DNAm and age in Fig. 1, for additional data see Supplementary file, Table 3).

DNA methylation levels (in PDE4C (CpG 1), ELOVL2 (CpG 1), RPA2 (CpG 2), EDARADD (CpG 2), DDO (CpG 1)) in buccal mucosa samples from German (gray, N = 368) and Japanese donors (N = 89, Japanese donors living in Japan = blue (N = 77), Japanese donors living in Germany = orange (N = 12). For genes with more than one analysed CpG site, the data for the CpGs with the highest correlation coefficients (R) are presented. Correlation coefficients (R) for German donors: R(PDE4C, CpG 1) = 0.95, R(ELOVL2, CpG 1) = 0.90, R(RPA2, CpG 2) = 0.89, R(EDARADD, CpG 2) = − 0.86, R(DDO CpG 1) =—0.73. Correlation coefficients (R) for Japanese donors: R(PDE4C, CpG 1) = 0.93, R(ELOVL2, CpG 1) = 0.89, R(RPA2, CpG 2) = 0.83, R(EDARADD, CpG 2) = − 0.81, R(DDO CpG 1) = − 0.62

CpG 7 in ELOVL2 and CpG 1 in DDO exhibited the weakest correlations between DNAm and age, with R < 0.75. These CpGs were excluded from further analysis.

The DNAm data for the 12 Japanese living in Germany (highlighted in Fig. 1) appear to be very similar to those of equally old Japanese living in Japan. Due to the low number of cases, no further statistical analysis was performed on this question.

Despite the very similar correlation between DNAm and age in Germans and Japanese, there was evidence for significant differences in DNAm at least at two sites. An ANCOVA using the Japanese data and the data of age- and sex-matched German subsamples revealed median p values of < 0.05 after 500 runs for PDE4C (CpG 2), RPA2 (CpG3), and EDARADD (CpG 2). A median p value close to 0.05 (0.0512) was calculated for ELOVL2 (CpG 8) (Table 2). The significance between the groups was most evident for EDARADD, CpG 2 (median p = 0.0061, p < 0.05 in 88.60% of 500 runs/subsamples) and PDE4C, CpG 2 (median p = 0.0132, p < 0.05 in 79.16% of 500 runs/subsamples). On the other hand side, median p values of > 0.3 were calculated for 11 of the analyzed CpGs (Table 2), indicating clearly no differences between Japanese and Germans.

Age prediction by models based on German training data did not reveal relevant differences between the Japanese sample and the age-and sex-matched German test samples

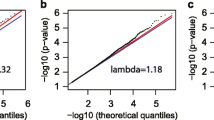

The means and medians of the MAEs calculated in 500 runs for the Japanese sample (Japanese test sample) and 500 different extracted age- and sex-matched German test samples were very similar (Germans: 4.14 years (mean), 4.14 years (median); Japanese: 4.38 years (mean), 4.38 years (median); Fig. 2).

Mean absolute errors (MAE, in years) of age estimation based on the German trainings data (“German” = German test subsamples (N = 83 each), “Japanese” = Japanese sample (N = 83)). Modeling was based on the German training data under exclusion of 500 extracted age- and sex-matched German test subsamples, respectively. The figure depicts the MAEs for 500 analyses for each group; the greater scattering of MAEs in the Germans is due to the extraction of 500 different German test groups, whereas the Japanese test group is the same group in all 500 analyses

There was no clear indication for biases resulting in a relevant systematic over- or underestimation of age, since the means as well as the medians of the mean deviation of the age gaps (from 500 runs) were very low in both test groups (Germans: 0.39 years (mean), 0.39 years (median); Japanese: − 0.40 years (mean), − 0.39 years (median); Fig. 3).

Mean deviation of the age gaps (difference between estimated and chronological ages, in years) after age estimation of the Japanese group (N = 83) and German test subsamples (N = 83 each) based on the German trainings data. Modeling was based on the German training data under exclusion of 500 extracted age- and sex-matched German subsamples, respectively. The figure depicts the mean deviations after 500 analyses for each group; the greater scattering of the German data is due to the extraction of 500 different German test groups, whereas the Japanese test group is the same group in all 500 analyses

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to contribute to the discussion about the possible effects of ethnicity/ancestry on age estimation based on DNAm by a direct comparison of DNAm patterns in German and Japanese samples that were analyzed in one lab under identical conditions. However, due to the interindividual variability of DNAm within a population [32,33,34], very large numbers of samples have to be analyzed to reliably prove differences between populations. Thus, the numbers of samples analyzed here (287 German samples, 83 Japanese samples in the age range 10–65 years) is a clear limitation of this study. Moreover, the size and the composition of the two groups were very different.

To overcome these limitations at least partly, we did not compare the Japanese group with only one age- and sex-matched German group, but with 500 age- and sex-matched German subgroups that were extracted from the total German group. The median p values of 500 ANCOVA analyses allow much more robust conclusions than the p values derived from just one analysis that includes only one randomly extracted German subgroup.

The strategy of subsampling was also applied in testing the performance of age prediction (based on the German training data set) in German test groups versus the Japanese test group. In each run, the model for age estimation was calculated only on the basis of the remaining training data, thus allowing a strict separation between training data and test data. That means that age estimation was performed in the Japanese test sample and in age- and sex-matched German test samples by 500 different models. The median MAEs give a robust impression of the performance of age estimation in the German and Japanese group. This strategy is an approach to reduce the impact of sampling effects, if the number of samples is limited.

The methodological approach of subsampling may be unusual and does not allow to present one model for age estimation (since, in fact 500 models were used). However, the aim of our work was not the presentation of a new model but to gain further insight into the question of the relevance of ethnicity/ancestry for age estimation based on DNAm.

In both German and Japanese samples, the DNA-methylation levels in buccal swabs were age-associated at all analyzed CpGs (in PDE4C, RPA2, ELOVL2, EDARADD, and DDO). This finding was to be expected, since similar data have already been published [5, 13, 29,30,31]. Differences in correlation coefficients (Table 1) were only small and may not be overinterpreted in light of the different (and in the Japanese group) limited number of samples in the donor groups.

Although the correlation between DNAm and age was very similar in Germans and Japanese, there was evidence of differences between the two groups in DNAm at some CpGs sites, most noticeable in EDARADD (CpG 2) and PDE4C (CpG 2). For these sites, the median p values of the 500 ANOVAs were p = 0.0061 (EDARADD (CpG 2)) and 0.0132 (PDE4C (CpG 2)); p values < 0.05 were calculated in 88.60% and 79.16% of the 500 runs, respectively (Table 2). These results can be interpreted as strong evidence for significant differences of DNAm at EDARADD (CpG 2) and PDE4C (CpG 2). The ANCOVA results for CpG 3 in RPA2 (median p value of 0.0391, p values < 0.05 in 56.88% of the 500 runs) at least suggest differences between the two groups.

One can only speculate about the biological background of such differences in the DNA methylation pattern between Germans and Japanese. Basically, genetic variations as well as living conditions may play a role [11, 22, 23]. The Japanese population may be genetically more homogeneous than other populations [35,36,37]. If so, also genetically determined DNA methylation patterns may be more homogeneous in the Japanese population, making differences to other populations more prominent. The finding that the DNAm data for the Japanese living in Germany appeared to be within the range of the other Japanese data may be another indication for the relevance of genetic factors; however, only 15 Japanese living in Germany were examined. It would be interesting to conduct further research on this topic under the inclusion of a higher number of cases.

If there is evidence for differences in the DNA methylation pattern at some CpGs, the question arises, if this may be relevant for age estimation models that include DNAm data of such CpGs. Our results demonstrated that means and medians of the MAEs were very similar in the German and Japanese cohort, and there was no clear indication for biases resulting in a relevant systematic over- or underestimation of age.

These findings do not contradict the evidence for significant differences in the DNAm levels at some CpGs in different genes. The age prediction models were based on data of 20 CpGs, for only two (to three) of them the ANCOVA analyses revealed evidence for differences between Japanese and Germans. Obviously, the high number of included “robust CpGs” (11 CpGs exhibited median p values > 0.3, see Table 2) prevented relevant effects of the differences in DNAm at two CpGs.

Nevertheless, our findings emphasize the impact of the ethnicity/ancestry on DNAm and are in line with the findings of other groups. Cho et al. [14] applied the age prediction model of Zbieć-Piekarska et al. [38] (derived from a Polish population, markers located in the genes ELOVL2, C1orf132, TRIM59, KLF14, and FHL2 genes) to blood samples from 100 Koreans. The authors reported that the age predictive performance of the model “is relatively consistent across different population groups,” although “the extent of the age association in Koreans was not identical to that of the Polish,” in particular at the loci FHL2 and C1orf132. Fleckhaus et al. [15] analyzed DNAm at five CpG sites in the genes ASPA, ITGA2B, PDE4C, and ELOVL2 in buccal mucosa samples of three independent population groups from the Middle East, West Africa, and Central Europe and reported “first evidence that the strength of correlation between methylation and chronological age and thus the accuracy of age prediction may vary between populations.” Thong et al. [13] analyzed blood samples from a local population comprising Chinese, Malays, and Indians (CpG sites in the genes ELOVL2, KLF14, TRIM59, and FHL2) and established age prediction models on the basis of the data from all three subpopulations. Using this model, they did not observe significant age prediction errors among the Chinese, Malays, and Indians. In contrast, notable differences in prediction accuracy were observed when the model was applied to a Polish and a French population (by using DNAm data reported by [5, 38]), the Polish samples were systematically underestimated. As possible reasons for these differences, the authors propose “methodology and instrumental variations during bisulfite conversion and/or pyrosequencing.”

Such methodological effects can be excluded for the here presented data of buccal mucosa samples of German and Japanese donors. These data suggest significant differences between the investigated populations in the methylation of at least two analyzed CpGs (EDARADD (CpG 2) and PDE4C (CpG 2)). Based on the presented data it cannot deduced, if the findings are just a matter of these two populations (Germans/Japanese), the very possibility of such a problem should lead to caution.

Forensic science should further address the influence of ethnicity/ancestry to optimize the potential of age estimation based on DNAm; a need for research has been already stated by others [9, 13, 15, 39, 40]. Thong et al. [13] suggested the retraining of age prediction models, if they are to be applied to individuals of other populations. This suggestion implies that retrained models are developed for all relevant populations and that the assignment of an unknown donor of a trace or a non-identified deceased to a specific population is known. Fleckhaus et al. [15] proposed “to include ancestry informative markers into the analysis as an additional factor for age prediction models.” Another approach would be to identify “robust” CpGs as basis for age prediction models that can be used regardless of the population of origin. Whatever approach is chosen, the targeted investigations of different populations are required at best by collaborative research with coordinated research strategies.

Change history

13 August 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note.

References

Maulani, C. and E.I. Auerkari, Age estimation using DNA methylation technique in forensics: a systematic review. Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 2020. 10(1).

Hanafi M, Soedarsono N, Auerkari E (2021) Biological age estimation using DNA methylation analysis: a systematic review. Sci Dent J 5(1):1–11

Weidner CI, Wagner W (2014) The epigenetic tracks of aging. Biol Chem 395(11):1307–1314

Böhme, P., A. Reckert, J. Becker, and S. Ritz-Timme, Molecular methods for age estimation. Rechtsmedizin, 2021.

Daunay A, Baudrin LG, Deleuze JF, How-Kit A (2019) Evaluation of six blood-based age prediction models using DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing. Sci Rep 9(1):8862

Jung SE, Lim SM, Hong SR, Lee EH, Shin KJ, Lee HY (2019) DNA methylation of the ELOVL2, FHL2, KLF14, C1orf132/MIR29B2C, and TRIM59 genes for age prediction from blood, saliva, and buccal swab samples. Forensic Sci Int Genet 38:1–8

Wozniak A, Heidegger A, Piniewska-Rog D, Pospiech E, Xavier C, Pisarek A, Kartasinska E, Boron M, Freire-Aradas A, Wojtas M, de la Puente M, Niederstatter H, Ploski R, Spolnicka M, Kayser M, Phillips C, Parson W, Branicki W, V. Consortium (2021) Development of the VISAGE enhanced tool and statistical models for epigenetic age estimation in blood, buccal cells and bones. Aging (Albany NY) 13(5):6459–6484

Han Y, Franzen J, Stiehl T, Gobs M, Kuo CC, Nikolić M, Hapala J, Koop BE, Strathmann K, Ritz-Timme S, Wagner W (2020) New targeted approaches for epigenetic age predictions. BMC Biol 18(1):71

Koop BE, Reckert A, Becker J, Han Y, Wagner W, Ritz-Timme S (2020) Epigenetic clocks may come out of rhythm-implications for the estimation of chronological age in forensic casework. Int J Legal Med 134(6):2215–2228

Dhingra R, Nwanaji-Enwerem JC, Samet M, Ward-Caviness CK (2018) DNA methylation age-environmental influences, health impacts, and its role in environmental epidemiology. Curr Environ Health Rep 5(3):317–327

Kader F, Ghai M (2017) DNA methylation-based variation between human populations. Mol Genet Genomics 292(1):5–35

Spolnicka, M., E. Pospiech, B. Peplonska, R. Zbiec-Piekarska, Z. Makowska, A. Pieta, J. Karlowska-Pik, B. Ziemkiewicz, M. Wezyk, P. Gasperowicz, T. Bednarczuk, M. Barcikowska, C. Zekanowski, R. Ploski, and W. Branicki, DNA methylation in ELOVL2 and C1orf132 correctly predicted chronological age of individuals from three disease groups. Int J Legal Med, 2017.

Thong Z, Tan JYY, Loo ES, Phua YW, Chan XLS, Syn CK (2021) Artificial neural network, predictor variables and sensitivity threshold for DNA methylation-based age prediction using blood samples. Sci Rep 11(1):1744

Cho S, Jung SE, Hong SR, Lee EH, Lee JH, Lee SD, Lee HY (2017) Independent validation of DNA-based approaches for age prediction in blood. Forensic Sci Int Genet 29:250–256

Fleckhaus J, Freire-Aradas A, Rothschild MA, Schneider PM (2017) Impact of genetic ancestry on chronological age prediction using DNA methylation analysis. Forensic Sci Int Genet Suppl Ser 6:e399–e400

Adkins RM, Krushkal J, Tylavsky FA, Thomas F (2011) Racial differences in gene-specific DNA methylation levels are present at birth. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 91(8):728–736

Bell JT, Pai AA, Pickrell JK, Gaffney DJ, Pique-Regi R, Degner JF, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK (2011) DNA methylation patterns associate with genetic and gene expression variation in HapMap cell lines. Genome Biol 12(1):R10

Banovich NE, Lan X, McVicker G, van de Geijn B, Degner JF, Blischak JD, Roux J, Pritchard JK, Gilad Y (2014) Methylation QTLs are associated with coordinated changes in transcription factor binding, histone modifications, and gene expression levels. PLoS Genet 10(9):e1004663

Moen EL, Zhang X, Mu W, Delaney SM, Wing C, McQuade J, Myers J, Godley LA, Dolan ME, Zhang W (2013) Genome-wide variation of cytosine modifications between European and African populations and the implications for complex traits. Genetics 194(4):987–996

Goncearenco A, LaBarre BA, Petrykowska HM, Jaratlerdsiri W, Bornman MSR, Turner SD, Hayes VM, Elnitski L (2021) DNA methylation profiles unique to Kalahari KhoeSan individuals. Epigenetics 16(5):537–553

Fagny M, Patin E, MacIsaac JL, Rotival M, Flutre T, Jones MJ, Siddle KJ, Quach H, Harmant C, McEwen LM, Froment A, Heyer E, Gessain A, Betsem E, Mouguiama-Daouda P, Hombert JM, Perry GH, Barreiro LB, Kobor MS, Quintana-Murci L (2015) The epigenomic landscape of African rainforest hunter-gatherers and farmers. Nat Commun 6:10047

Li Y, Xu Y, Liu T, Chang H, Yang X (2021) The regulation mechanisms and the Lamarckian inheritance property of DNA methylation in animals. Mamm Genome 32(3):135–152

Feil R, Fraga MF (2012) Epigenetics and the environment: emerging patterns and implications. Nat Rev Genet 13(2):97–109

Horvath S, Gurven M, Levine ME, Trumble BC, Kaplan H, Allayee H, Ritz BR, Chen B, Lu AT, Rickabaugh TM, Jamieson BD, Sun D, Li S, Chen W, Quintana-Murci L, Fagny M, Kobor MS, Tsao PS, Reiner AP, Edlefsen KL, Absher D, Assimes TL (2016) An epigenetic clock analysis of race/ethnicity, sex, and coronary heart disease. Genome Biol 17(1):171

Tajuddin SM, Hernandez DG, Chen BH (2019) N Noren Hooten, NA Mode, MA Nalls, AB Singleton, N Ejiogu, KN Chitrala, AB Zonderman, MK Evans, Novel age-associated DNA methylation changes and epigenetic age acceleration in middle-aged African Americans and whites. Clin Epigenetics 11(1):119

Daca-Roszak P, Jaksik R, Paczkowska J, Witt M, Zietkiewicz E (2020) Discrimination between human populations using a small number of differentially methylated CpG sites: a preliminary study using lymphoblastoid cell lines and peripheral blood samples of European and Chinese origin. BMC Genomics 21(1):706

Husquin LT, Rotival M, Fagny M, Quach H, Zidane N, McEwen LM, MacIsaac JL, Kobor MS, Aschard H, Patin E, Quintana-Murci L (2018) Exploring the genetic basis of human population differences in DNA methylation and their causal impact on immune gene regulation. Genome Biol 19(1):222

Naue J, Hoefsloot HCJ, Kloosterman AD, Verschure PJ (2018) Forensic DNA methylation profiling from minimal traces: How low can we go? Forensic Sci Int Genet 33:17–23

Naue J, Hoefsloot HCJ, Mook ORF, Rijlaarsdam-Hoekstra L, van der Zwalm MCH, Henneman P, Kloosterman AD, Verschure PJ (2017) Chronological age prediction based on DNA methylation: Massive parallel sequencing and random forest regression. Forensic Sci Int Genet 31:19–28

Bekaert B, Kamalandua A, Zapico SC, Van de Voorde W, Decorte R (2015) Improved age determination of blood and teeth samples using a selected set of DNA methylation markers. Epigenetics 10(10):922–930

Weidner CI, Lin Q, Koch CM, Eisele L, Beier F, Ziegler P, Bauerschlag DO, Jockel KH, Erbel R, Muhleisen TW, Zenke M, Brummendorf TH, Wagner W (2014) Aging of blood can be tracked by DNA methylation changes at just three CpG sites. Genome Biol 15(2):R24

Fraser HB, Lam LL, Neumann SM, Kobor MS (2012) Population-specificity of human DNA methylation. Genome Biol 13(2):R8

Giri AK, Bharadwaj S, Banerjee P, Chakraborty S, Parekatt V, Rajashekar D, Tomar A, Ravindran A, Basu A, Tandon N, Bharadwaj D (2017) DNA methylation profiling reveals the presence of population-specific signatures correlating with phenotypic characteristics. Mol Genet Genomics 292(3):655–662

Giuliani C, Sazzini M, Bacalini MG, Pirazzini C, Marasco E, Fontanesi E, Franceschi C, Luiselli D, Garagnani P (2016) Epigenetic variability across human populations: a focus on DNA methylation profiles of the KRTCAP3, MAD1L1 and BRSK2 Genes. Genome Biol Evol 8(9):2760–2773

Wang Y, Lu D, Chung YJ, Xu S (2018) Genetic structure, divergence and admixture of Han Chinese Japanese and Korean populations. Hereditas 155:19

Horai S, Murayama K, Hayasaka K, Matsubayashi S, Hattori Y, Fucharoen G, Harihara S, Park KS, Omoto K, Pan IH (1996) mtDNA polymorphism in East Asian populations, with special reference to the peopling of Japan. Am J Hum Genet 59(3):579–590

Yasumizu Y, Sakaue S, Konuma T, Suzuki K, Matsuda K, Murakami Y, Kubo M, Palamara PF, Kamatani Y, Okada Y (2020) Genome-wide natural selection signatures are linked to genetic risk of modern phenotypes in the japanese population. Mol Biol Evol 37(5):1306–1316

Zbiec-Piekarska R, Spolnicka M, Kupiec T, Parys-Proszek A, Makowska Z, Paleczka A, Kucharczyk K, Ploski R, Branicki W (2015) Development of a forensically useful age prediction method based on DNA methylation analysis. Forensic Sci Int Genet 17:173–179

Montesanto A, D’Aquila P, Lagani V, Paparazzo E, Geracitano S, Formentini L, Giacconi R, Cardelli M, Provinciali M, Bellizzi D, Passarino G (2020) A new robust epigenetic model for forensic age prediction. J Forensic Sci 65(5):1424–1431

Al-Ghanmy, H.S.G., N.A.M. Al-Rashedi, and A.Y. Ayied, Age estimation by DNA methylation levels in Iraqi subjects. Gene Reports, 2021. 23.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, RI 704/4–1 and WA 1706/8–1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JBe and SRT wrote the draft of this paper. SRT provided the idea and the concept of this work and gave support and guidance in all project phases. JBe analyzed samples and evaluated data. AR und PB gave technical advice and was responsible for troubleshooting. SBE carried out the statistical evaluation and developed the model for age prediction. BEK, JBl and TG, and MT collected and analyzed samples. WW supported the study design and gave technical advice. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and gave their consent for the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human tissue were in concordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/ or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (approved by the Ethics Committee at the Medical Faculty of Heinrich-Heine University: HEBE-project, study number 5049). This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and/ or from legal representatives.

Conflicts of interest

WW is cofounder of Cygenia GmbH (www.cygenia.com) that may provide a service for analysis of epigenetic age. Apart from this, the authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Becker, J., Böhme, P., Reckert, A. et al. Evidence for differences in DNA methylation between Germans and Japanese. Int J Legal Med 136, 405–413 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-021-02736-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-021-02736-3