Abstract

The genetic underpinnings of heart rate regulation are only poorly understood. In search for genetic regulators of cardiac pacemaker activity, we isolated in a large-scale mutagenesis screen the embryonic lethal, recessive zebrafish mutant schneckentempo (ste). Homozygous ste mutants exhibit a severely reduced resting heart rate with normal atrio-ventricular conduction and contractile function. External electrical pacing reveals that defective excitation generation in cardiac pacemaker cells underlies bradycardia in ste −/− mutants. By positional cloning and gene knock-down analysis we find that loss of dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase (DLST) function causes the ste phenotype. The mitochondrial enzyme DLST is an essential player in the citric acid cycle that warrants proper adenosine-tri-phosphate (ATP) production. Accordingly, ATP levels are significantly diminished in ste −/− mutant embryos, suggesting that limited energy supply accounts for reduced cardiac pacemaker activity in ste −/− mutants. We demonstrate here for the first time that the mitochondrial enzyme DLST plays an essential role in the modulation of the vertebrate heart rate by controlling ATP production in the heart.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diseases of cardiac pacemaker cells such as the sick sinus syndrome are the most common indications for cardiac pacemaker implantations [12, 27]. However, little is known about the genetic underpinnings of cardiac pacemaker function in vertebrates. Genetic studies in humans have demonstrated a significant contribution of genetic factors in heart rate regulation [11, 12, 38]. For instance, it was found that autosomal recessive mutations of the sodium-channel SCN5A lead to familial sick sinus syndrome [4]. Furthermore, a combined genome-wide association study that included data from 181,171 individuals recently led to the identification of 14 distinct genomic regions that significantly impact on heart rate regulation [12]. Interestingly, in these regions both, genes already known to be involved in heart rate regulation such as the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel 4 (HCN4), but also several novel modifier genes are located [12].

In recent years, large-scale forward genetic screens in zebrafish helped to dissect novel genetic underpinnings of cardiac rhythm control [10, 20, 31, 34, 42]. For instance, characterization of the zebrafish mutants island beat and tremblor revealed an essential role of the L-type calcium channel alpha 1 subunit and the sodium–calcium exchanger NCX1h in the pathogenesis of atrial and ventricular fibrillation, respectively [15, 24, 37]. Furthermore, characterization of a bradycardic zebrafish mutant and gene knock-down studies recently revealed an essential role of Shox2-Islet1 signaling in the control of cardiac pacemaker activity [21].

In search for novel regulators of basal heart rate we dissected here the genetic cause of the embryonic-lethal recessive ethylnitrosourea (ENU)-induced bradycardic zebrafish mutant schneckentempo (ste), and find that DLST, a mitochondrial enzyme that acts within the citric acid cycle to warrant ATP production, is essential for cardiac pacemaker cells.

Materials and methods

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were bred and maintained at 28.5 °C as described by Westerfield [47]. Pictures and movies were recorded at 48 h post-fertilization (hpf) and 72 hpf. To inhibit pigmentation 0.003 % 1-phenyl-2-thiourea was added to the regular embryo medium E3 (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2, 0.33 mM MgSO4 dissolved in water). Heart rate was counted at 48, 72, 96 and 120 hpf at room temperature.

We measured fractional shortening by videomicroscopy at room temperature and compared the diameters of the ventricle at the end of contraction (systole) and relaxation (diastole) as described before [31].

DNA from 48 ste −/− mutant and 48 wild-type embryos was pooled and bulked segregation analysis was performed as described before [33]. The critical genomic interval for ste was defined by genotyping 613 mutant embryos for polymorphic markers in the area. RNA from ste −/− mutant and wild-type embryos was isolated using TRIZOL Reagent (Life Technologies) and reverse transcribed. cDNA of a total of 30 mutant and wild-type embryos was sequenced. Genomic DNA from ten ste −/− mutant and ten wild-type embryos was sequenced around the point mutation.

Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out according to standard protocols with the SYBR-Green method (Bio-Rad) and an Eppendorf Realplex-2 cycler. cDNA was generated from RNA of 72 hpf homozygous ste mutant and sibling embryos using oligo(dT) primer and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen).

For all Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotide injection procedures, the TE wild-type strain was used. Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotides (MO; Gene Tools, LLC) were directed against the translational start site (5′-TCAGACAGCGGGAATGACACAACAT-3′) of zebrafish DLST (MO-DLST-start), the splice donor site of exon 5/intron 5 (5′-CATGTTGCCTTCTTACCTTTCTCCC-3′) of zebrafish DLST on chromosome 17 (MO-DLST-splice), the splice donor site exon 3/intron 3 (5′-ACTGGATGTCAGATCGGTACCTTAA-3′) of DLDH on chromosome 25 (MO-DLDH-splice), the splice donor site exon 5/intron 5 of zebrafish OGDH a (5′-AGACCTTCAAATCTTCTACCTGTGC-3′) on chromosome 8 (MO-OGDHa-splice) and the splice donor site exon 7/intron 7 of zebrafish OGDH b (5′-TTCTTGTTGTCCTGACTTACCTCTA-3′) on chromosome 10 (MO-OGDHb-splice). DLST, OGDH and DLDH Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotides or a standard control Morpholino (MO-control) were microinjected into zebrafish embryos up to the 4-cell stage.

For histology, embryos were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde and embedded in JB-4 (Polysciences, Inc). Then, 5-μm sections were cut, dried, and samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Transmission electron micrographs (TEM) were obtained essentially as described previously [37]. Whole-mount antisense RNA in situ hybridization was carried out as described previously [22, 23] using a digoxigenin-labeled antisense probe for zebrafish DLST.

Calcium imaging was performed as described before [28]. Wild-type and ste −/− mutant embryos were injected with 1 nl of a 250 μM stock solution of calcium green-1 dextran (Molecular Probes) at the one-cell stage. At 72 hpf videos were recorded with a Proxitronic (Proxivision) camera at 29.97 frames per second. Relative fluorescence of the atrium and ventricle were analyzed with custom-made software [31].

Electrical stimuli were applied by a pacemaker (PACE100H; Osypka Medical GmbH). Patch clamp pipettes filled with 3 M potassium chloride with a resistance of 2–10 MΩ were used as cathode. As described before [31, 37], this electrode was approached to either the atrium or ventricle with a micromanipulator under microscopic control. The heart chambers were stimulated at different frequencies (80–150/min), applying 1–12 V.

Sodiumfluoroacetate (SFA) (FCH2CO2Na) was added at a concentration of 0.067 or 0.2 mg/ml to the medium of dechorionated wild-type zebrafish at 24 hpf and exchanged every 24 h. SFA blocks aconitate hydratase thereby inhibiting the citric acid cycle [36].

2,4-Dinitrophenol (DNP) (Sigma Aldrich) was added at a concentration of 10 µM to the medium of dechorionated wild-type zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf. 2,4-Dinitrophenol uncouples the respiratory chain reaction from ATP production [8, 39, 46]. At high concentrations it is known to decrease ATP production [9, 46], whereas at lower concentrations predominantly reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is influenced [8, 39].

Idebenone (IDB, Sigma Aldrich) proved to act antioxidative against ROS and to promote mitochondrial function and ATP production after acute exposure by increasing the effectiveness of the respiratory chain reaction [6, 19]. Zebrafish embryos were incubated at 48 hpf at a concentration of 0.3 µM dissolved in ethanol.

ATP content was measured with a luciferase-based assay (ATP Determination Kit A22066, Invitrogen, Life Technologies Corporation) with recombinant firefly luciferase and d-luciferin. Zebrafish embryos were mechanically lysed and luminescence was immediately quantified by Berthold Luminometer Lumat LB 9501. The ATP content was calculated by creating an ATP-luminescence standard curve in Microsoft Excel.

Data of protein expression was obtained from the protein expression database MOPED (http://www.proteinspire.org/MOPED/mopedviews/proteinExpressionDatabase.jsf) and PaxDb (http://www.pax-db.org).

All results are depicted as arithmetic mean ± standard error of mean from at least two independent experiments. Figures were created with Microsoft Excel. Area measurements in TEM were conducted with ArchiCAD (Graphisoft).

Statistical analysis was performed in Graph Pad Prism. Comparisons between experimental groups were performed using t test. Differences are considered significant at a p < 0.05 significance level and marked with “*”, very significant with p < 0.01 are labeled “**” and extremely significant with p < 0.001 are labeled “***”.

Results

Zebrafish mutant schneckentempo exhibits bradycardia

In search for genetic modulators of the vertebrate heart rate, we isolated in a large-scale ENU-mutagenesis screen (Tübingen 2000) the embryonic-lethal zebrafish mutant line schneckentempo (ste), which displays a severely reduced resting heart rate, so-called bradycardia. Besides their reduced heart rate, ste −/− mutant zebrafish embryos exhibit decreased motility both spontaneously and in response to touch.

Up to 72 h post-fertilization (hpf), ste −/− mutant embryos are indistinguishable from their wild-type littermates in regard to cardiac structure and function. However, at 72 hpf ste −/− mutant embryos display severe bradycardia with a heart rate of 81 ± 4.7 beats per minute (bpm) compared to 143 ± 4.7 bpm in wild-type siblings (n = 16, p < 0.0001) measured at room temperature. During further development the heart rate of ste −/− mutant embryos even further decreases at 96 hpf to 73 ± 2.3 bpm compared to 167 ± 5.7 bpm (n = 16, p < 0.0001) and to 68 ± 6.5 bpm compared to 163 ± 3.9 bpm in wild-type siblings at 120 hpf (n = 16, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1c). Although the heart rate is significantly reduced in ste −/− mutants, similar to the situation in wild-types, ste −/− hearts contract regularly and sequentially, whereby each atrial contraction is followed by a ventricular contraction, indicating unaffected atrio-ventricular conduction in ste −/− hearts. Similarly, cardiac contractility is not reduced in homozygous ste mutants. As shown in Fig. 1d ventricular fractional shortening is 53 ± 2.2 % in ste −/− mutants and 55 ± 3.1 % in wild-type ste siblings at 72 hpf (n = 5, p = 0.7096), a time point where severe bradycardia is already manifest in ste −/− mutant embryos.

Effects of the ste mutation on cardiac function. a, b Lateral view of wild-type (wt) (a) and ste −/− mutant (b) embryos at 72 h post-fertilization (hpf). ste −/− mutants (b) develop blood congestion at the cardiac inflow tract and a pericardial edema. c Heart rate at different time points in ste −/− mutants (red) and wild-type littermates (blue). Bradycardia in ste −/− mutants starts at 48 hpf and becomes more severe during further embryonic development. d Ventricular fractional shortening is unaffected in ste −/− mutants compared to wild-type littermates at 72 hpf (53 ± 2.2 vs. 55 ± 3.1 %, n = 5, p = 0.7096), 96 hpf (58 ± 3.2 vs. 57 ± 1.9 %, n = 5, p = 0.7956) and 120 hpf (59 ± 1.9 vs. 61 ± 1.8 %, n = 5, p = 0.5586)

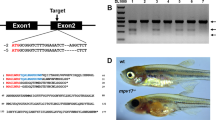

The ste locus encodes for zebrafish dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase

To identify the mutation causing the recessive ste −/− mutant phenotype, we performed a genome-wide study of microsatellite marker segregation and linked ste to zebrafish chromosome 17. Recombination analysis of 1,226 ste −/− mutant embryos restricted ste −/− to a genomic interval flanked by the microsatellite markers z13385 and z381. Genetic fine-mapping further narrowed down the ste locus to the two bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) BX005229 and AL935141, and finally to two open reading frames encoding proteins highly homologous to human prospero-related homeobox 2 (prox2) and dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase (DLST) (Fig. 2a). To identify the site of the ENU-induced mutation in ste, we sequenced the entire zebrafish coding sequence of the 2 genes zprox2 and zdlst from wild-type and ste −/− mutant genomic DNA and identified the ste mutation to be a guanine to adenine nucleotide transition in the splice donor site of intron 5 of the zdlst gene (ENSDARG00000014230). Zdlst cDNA analysis of ste −/− mutants reveals that upstream of the mutated splice donor site an alternative splice site is used, resulting in partial exon skipping with deletion of 11 nucleotides (Fig. 2b). The consecutive reading frame shift generates an early stop codon and is predicted to cause premature termination of translation of dlst in ste −/− mutants (Supplementary Fig. 1). Next, to evaluate if the ste mutation impairs RNA stability, we quantified RNA levels by whole-mount RNA antisense in situ staining and qRT-PCR and find reduced levels of dlst RNA down to 10.7 ± 5.3 % in ste −/− mutants (n = 4, p = 0.0414) in comparison to wild-type ste siblings (Fig. 2e).

ste encodes for dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase (dlst). a Integrated genetic and physical map of the ste locus. The ste mutation interval is flanked by the microsatellite markers z13385 and z381 and encodes two open reading frames, zebrafish dlst and prox2. b Within the coding sequence of zdlst a point mutation (G→A) was identified at the splice donor site of intron 5 leading to aberrant pre-mRNA splicing and the premature termination of DLST translation. An arrow marks the mutated base. c, d Spatial expression of dlst by whole-mount antisense RNA in situ hybridization of wt and ste −/− embryos at 72 hpf. c dlst is ubiquitously expressed with pronounced levels in the brain, skeletal muscle, fins and heart of wild-type embryos. d Strongly reduced dlst mRNA levels in ste −/− mutants compared to wild-type littermates. e Quantitative real-time PCR of ste −/− mutants and wild-type siblings. Nonsense mediated dlst-RNA decay in ste −/− mutants compared to wild-type siblings at 72 hpf

DLST is an essential component of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex of the citric acid cycle and is expressed ubiquitously in mammals with pronounced levels in the liver, the kidneys, the central nervous system and the heart (databases for protein expression MOPED and PaxDb). As shown in Fig. 2c, we find dlst RNA to be ubiquitously distributed in wild-type zebrafish embryos, with enhanced levels in the heart, skeletal muscle and pectoral fins. Zebrafish DLST is highly homologous to human DLST with a 74 % overall amino acid identity (Supplementary Fig. 1). The ste mutation resides within the NH2-terminal lipoyl domain of DLST and hence the COOH-terminal catalytic domain of DLST is predicted not to be translated in ste −/− mutants leading to loss of DLST function.

To validate that loss of DLST function indeed is responsible for the ste phenotype, we inactivated zdlst by Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotide mediated gene knock-down, targeting either the translation initiation site (MO-DLSTstart) or the splice donor site of the exon 5/intron 5 boundary (MO-DLSTsplice) of zdlst, where the ste mutation resides. Injection of 4.2 ng MO-DLSTsplice into wild-type zebrafish embryos leads to bradycardia (89 ± 4 bpm) in 72 hpf embryos, whereas MO-control injected embryos exhibit normal heart rates of 132 ± 1 bpm (n = 14, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3d). Similar results were obtained by injection of 21.2 ng of MO-DLSTstart (heart rate at 72 hpf in MO-DLSTstart morphants 92 ± 6 bpm; in controls 139 ± 2 bpm; n = 10, p < 0.0001), indicating that the ste mutation leads to complete loss of zDLST function.

Targeted knockdown of zdlst phenocopies the ste −/− mutant phenotype. a, b Knockdown of zdlst by injection of Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotides (MO-DLSTsplice) (a) phenocopies the ste mutant phenotype (b), whereas injection of the same amount of standard control Morpholino (MO-control) (c) does not impact on heart rate. d Similar to ste −/− mutants, heart rate of DLSTsplice morphants is significantly reduced compared to MO-control-injected embryos at 72 hpf. e, f Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of wild-type and ste −/− ventricular myocardium at 72 hpf. Scale bar represents 3 µM. e In wild-type myocardium, mitochondria display regular structure of inner and outer membrane and cristae. f In ste −/− myocardium, mitochondria display derangement of structure with severely reduced numbers of cristae. g, h TEM of wild-type and ste −/− skeletal muscle at 72 hpf. Scale bar represents 1 µM. g In wild-type skeletal muscle mitochondria exhibit regular morphology. h In ste −/− skeletal muscle mitochondria are characterized by large vacuoles and reduced numbers of cristae

Loss of DLST function induces mitochondrial degeneration in schneckentempo mutants

Dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase is known to localize to the mitochondrial matrix where it catalyzes within the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex the citric acid cycle. Loss of mitochondrial enzyme function is often accompanied by morphological alterations of mitochondria [1, 7, 25, 45]. To determine if this is also the case in DLST-deficient ste −/− mutant zebrafish, we analyzed the mitochondrial ultrastructure in ventricular and atrial cardiomyocytes of ste −/− mutants by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We find in ste −/− hearts large vacuoles either in the vicinity of mitochondria or within mitochondria. Their position is shifted from the interfibrillar to the sub-sarcolemmal and perinuclear regions as seen in other mitochondriopathies involving the heart [25]. Furthermore, similar to other mitochondriopathies [25] mitochondrial density is altered in ste −/− myocardium compared to wild-type embryos (2.20 ± 0.29 % in ste −/− versus 1.01 ± 0.20 % in wild-type, n = 100, p = 0.001) and the average size of mitochondria is significantly enlarged (0.67 ± 0.072 µm2 in ste −/− versus 0.35 ± 0.027 µm2 in wild types, n = 100, p < 0.0001). In addition, as shown in Fig. 3 mitochondria in ste −/− mutant hearts are pleomorphic, irregularly shaped and contain reduced numbers of cristae (4.8 ± 0.76 in ste −/− and 15.2 ± 1.7 in wild-type, n = 15, p = 0.0001). Similar changes on mitochondrial morphology could be observed in other ste −/− mutant tissues such as the skeletal muscle (Fig. 3g, h).

Resting heart rate depends on the citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle guarantees energy production by metabolizing amino acids, fatty acids and carbon hydrates [13]. Within the citric acid cycle, the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex is the rate-limiting component [30] and consists of three subunits: E1—oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH), E2—dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase (DLST) and E3—dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (DLDH) [5, 18, 26]. To evaluate if the effect of DLST on zebrafish heart rate is mainly mediated via the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, we inactivated the other subunits of this complex by Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotide mediated knock-down in zebrafish. To do so, we first identified the zebrafish subunit E1 and subunit E3 orthologous sequences and designed corresponding Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotides to inactivate their function. When co-injecting 10.4 ng Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotides targeting the splice site of exon 5 of subunit E1a (MO-E1a) and 5.4 ng of MO-E1b targeting the splice site of exon 7 of subunit E1b into zebrafish wild-type embryos, 93 % (n = 40) of the injected embryos displayed significantly reduced heart rates at 72 hpf (100 ± 6 bpm, in controls 133 ± 2 bpm, n = 10, p < 0.0001) similar to homozygous ste −/− mutant embryos (Fig. 4e). Similarly, after injection of 21.2 ng of Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotide directed to the splice site of exon 3 of subunit E3 (MO-E3), severe bradycardia with 90 ± 7 bpm could be observed in 89 % (n = 18) of the injected embryos at 72 hpf, indicating that indeed loss of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex activity of the citric acid cycle accounts for bradycardia in ste −/− mutants (Fig. 4e).

Blockade of the citric acid cycle phenocopies the ste −/− mutant phenotype. a–c, g Morpholino-modified antisense oligonucleotide mediated knockdown of OGDH subunit E1 (MO-E1) (a) or DLDH subunit E3 (MO-E3) (b) of the citric acid cycle phenocopies the ste −/− bradycardia (g), whereas injection of a control Morpholino has no effect (c, g). d–g Incubation of wild-type embryos with the citric acid cycle blocker sodiumfluoroacetate (SFA) and the respiratory chain uncoupler 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) phenocopies the heart rate defect of ste −/− mutant embryos in a dose-dependent manner

Finally, to evaluate whether basal heart rate is regulated via the citric acid cycle or merely the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, we blocked the citric acid cycle by a pharmacological approach independent of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. To do so, we inhibited aconitate hydratase and thereby efficiently citric acid cycle function by sodiumfluoroacetate (SFA) [36]. After incubation of 24 hpf zebrafish wild-type embryos for 48 h in 0.2 mg/ml SFA 83 % (n = 30) of the wild-type embryos exhibit similar to ste −/− mutants bradycardia with an average heart rate of 78 ± 3 bpm compared to 125 ± 3 bpm in controls (n = 11, p < 0.0001). Remarkably, incubation of wild-type embryos in much lower doses of SFA (0.067 mg/ml) also impacts on heart rate, but with a less pronounced effect (heart rate 97 ± 3 bpm and 125 ± 3 bpm in controls; n = 11, p < 0.0001, Fig. 4e), demonstrating a dose-dependent effect of citric acid cycle inhibition on zebrafish heart rate. In summary, these findings indicate an essential role of the citric acid cycle in zebrafish heart rate control.

Reduced ATP levels lead to cardiac dysfunction in ste −/− mutant zebrafish

The citric acid cycle is an essential metabolic process that ensures energy delivery under normoxic conditions. Within the citric acid cycle GTP (guanine-tri-phosphate), NADH (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) and FADH2 (reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide) are produced and ultimately converted to ATP by the respiratory chain reaction [13]. Hence, to evaluate the impact of loss of DLST function on mitochondrial ATP production, we next measured ATP content in ste −/− mutants with a luciferase-based assay. As depicted in Fig. 5a, we find severely reduced levels of ATP in ste −/− mutants (34 ± 0.5 %, 75 ± 12 pmol) in comparison to wild-type zebrafish embryos (218 ± 32 pmol, n = 10, p = 0.0006) or wild-type ste siblings (86 ± 17 %, 188 ± 37 pmol, n = 10, p = 0.0096).

Reduced ATP levels in ste −/− mutants lead to sinus bradycardia. a ATP content of ste −/− mutant embryos is significantly reduced compared to wild-type embryos (TE strain) and wild-type ste siblings (ste +/−;+/+ ), whereas ATP content between TE strain and wild-type ste siblings does not significantly differ. Dead zebrafish embryos serve as a control (72 hpf). The ATP content of embryos that were incubated with SFA and DNP is also significantly reduced and resembles the ATP content of ste −/− mutant embryos. b The coenzyme Q10 analogue Idebenone partially rescues heart rate in ste −/− mutant embryos that were incubated with this drug. c ste −/− mutants were incubated at increased temperature throughout embryonic development and ventricular fractional shortening was measured in wild-type and ste −/− mutant embryos at 72, 96 and 120 hpf. Fractional shortening of ste −/− mutant embryos under normal conditions (29 °C) does not significantly differ compared to wild-type embryos. Fractional shortening is reduced in ste −/− mutant embryos raised at 32 °C at (48 ± 2.1 vs. 54 ± 3.9 %, n = 10, p = 0.0358), 96 hpf (18 ± 4.0 vs. 56 ± 2.0 %, n = 10, p < 0.0001) and 120 hpf (10 ± 3.5 vs. 56 ± 2.1 %, n = 10, p < 0.0001)

To further evaluate if indeed reduction of ATP directly accounts for bradycardia in ste −/− mutants, we next pharmacologically inhibited ATP production by incubation with 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) [8, 9, 46]. As shown in Fig. 5a, we find an average reduction of ATP levels in 72 hpf wild-type zebrafish embryos incubated for 24 h in 10 µM DNP down to 26 % of the ATP content of wild-type embryos (n = 10, p < 0.0001) accompanied by severe reduction of resting heart rate of DNP incubated embryos down to 80 ± 4 bpm compared to 125 ± 3 bpm in controls (n = 10, p < 0.0001). To further prove that the effect of loss of DLST on resting heart rate is mainly mediated via ATP, we incubated ste −/− mutant zebrafish embryos with the coenzyme Q10 analogue Idebenone (IDB), a known enhancer of global mitochondrial function and ATP production [6, 19]. As shown in Fig. 5b, incubation with 0.3 µM IDB leads to an increase of the resting heart rate of ste −/− mutants from 81 ± 1.8 to 117 ± 2.1 bpm (n = 10, p < 0.0001), indicating partial rescue of bradycardia in ste −/− mutants via enhanced mitochondrial function. In summary, these findings implicate an essential role of DLST for zebrafish heart rate control via ATP production.

Interestingly, as shown above, reduced ATP levels mediated by loss of DLST function, seem not to directly impact on ventricular cardiomyocyte contractile function, since fractional shortening of ste −/− mutants is not reduced under unstressed conditions, in comparison to the wild-type siblings. Hence, to evaluate if enhancement of ATP consumption might unmask the expected effect of ATP reduction on cardiomyocyte contractile function, we next raised the offspring of ste heterozygous embryos at an increased temperature of 32 °C [29, 32]. As shown in Fig. 5c, under normal rearing conditions of 29 °C, ste −/− mutant embryos exhibit preserved cardiac systolic function throughout the first 5 days of embryonic development, whereas raising the offspring at 32 °C unmasks impaired systolic ventricular function in ste −/− mutants. After 72 hpf ventricular fractional shortening is reduced to 48 ± 2.1 % in offspring raised at 32 °C compared to 54 ± 1.7 % in ste −/− mutants raised at 29 °C (n = 10, p = 0.0358), at 96 hpf down to 18 ± 4.0 % compared to 58 ± 1.8 % (n = 10, p < 0.0001) and at 120 hpf down to 9.9 ± 3.5 % compared to 51 ± 2.8 % (n = 10, p < 0.0001) in embryos raised at 29 °C.

Loss of DLST leads to pacemaker cell dysfunction in ste −/− mutant zebrafish

The observed reduced resting heart rate in ste −/− mutants might be either caused by defective excitation generation in the pacemaker site of the heart, the so-called sinus node, by slowed-down myocardial excitation propagation in the atrium and the ventricle, or by uncoupling of excitation and contraction. To decipher the underlying pathophysiology of ste −/− bradycardia, we next assayed cardiac calcium transients [23] and performed external electrical pacing experiments. First, to evaluate if abnormal cardiac excitation propagation or excitation–contraction coupling account for the ste phenotype, we monitored free cytosolic myocardial calcium and cardiac contraction simultaneously in ste −/− mutant hearts at 72 hpf. As in wild-types, cardiac excitation in ste −/− mutant embryos starts in the atrium, and then moves from the atrium towards the ventricle. Each atrial calcium wave is followed by a calcium wave through the ventricle and each calcium wave is accompanied by cardiac chamber contraction (n = 15/15, exemplary Supplementary Movie), indicating that cardiac excitation in ste −/− mutants is correctly initiated in the atrium, but with a much lower frequency compared to wild-types (Fig. 6a).

a Selective atrial stimulation of ste −/− mutants at 72 hpf reconstitutes heart rate to normofrequency as depicted by simultaneous measurements of atrial (blue) and ventricular (green) cytoplasmic calcium transients. b Schematic description of the experimental setup for selective atrial stimulation using an electric stimulator

Next, to evaluate if either slowed excitation initiation in the cardiac pacemaker cells, or a prolonged electrical refractory period of cardiomyocytes underlies the ste bradycardic phenotype, we performed selective cardiac stimulation in ste −/− mutant embryos (Fig. 6b). As shown in Fig. 6a, similar to the situation in wild-type hearts, selective electrical atrial stimulation above the endogenous increases the heart rate in ste −/− mutants from around 80 up to 150 bpm (n = 15, exemplary Supplementary Movie), whereby each atrial stimulation is followed by coordinated sequential atrial and ventricular contractions. In summary, these findings indicate that bradycardia in ste −/− mutants is caused by defective excitation initiation in atrial pacemaker cells, so-called sinus bradycardia, and not by defective excitation propagation or excitation–contraction uncoupling.

Discussion

In search for genetic regulators of the vertebrate heart rate, we isolated in a large-scale mutagenesis screen the bradycardic zebrafish mutant schneckentempo (ste) and find here by positional cloning that loss of dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase (DLST) function leads to impaired cardiac pacemaker function in ste −/− mutant embryos. DLST is an essential component of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex of the citric acid cycle localized in mitochondria, and hence involved in ATP production. Accordingly, we find severely altered mitochondrial morphology and reduced ATP levels in ste −/− mutant zebrafish embryos, suggesting that limited energy supply is the molecular cause for the observed bradycardia in ste −/− mutants.

The essential role of regular ATP production and normal ATP levels for heart rate regulation of the embryonic zebrafish heart is further confirmed by the pharmacological inhibition of ATP production with the citric acid cycle blocker sodiumfluoroacetate SFA and the respiratory chain reaction uncoupler dinitrophenol DNP. Incubation of wild-type zebrafish embryos with either SFA or DNP significantly reduces global ATP levels in the zebrafish embryos as observed in the ste −/− zebrafish mutants and causes reduced resting heart rates.

In contrast to this, resting heart rate in ste −/− mutants can partially be rescued by incubation with the coenzyme Q10 analogue Idebenone, which is known to promote ATP production and improve mitochondrial function [6, 19], thereby further confirming that the effect of loss of DLST on resting heart rate is mainly mediated via ATP.

Cardiac calcium transient measurements and external electrical pacing experiments reveal that under normal conditions loss of DLST rather selectively impacts on cardiac pacemaker cell function, whereas contractile force is not significantly altered in ste −/− mutants, although ATP levels are globally reduced. However, enhancement of ATP consumption by rearing ste −/− mutants at higher temperatures unmasks an impact of DLST also on ventricular contractile function. DLST is known to catalyze energy generation in the citric acid cycle in the mitochondrial matrix, where GTP, NADH and FADH2 are produced. The energy equivalents NADH and FADH2 are then converted to ATP in the respiratory chain complex in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Normally, this oxidative phosphorylation accounts for more than 90 % of the energy production of cells under normoxic conditions [14, 17, 35, 43]. Patients suffering from reduced activity of DLST develop lactate acidosis and usually die early during childhood. Similar to ste −/− mutants, cardiac morphology appears to be unaltered in DLST-deficient patients [5, 18, 26]. However, all reported cases in humans feature a residual DLST activity of 5–25 % [5, 18, 26]. By contrast, we expect no residual activity of DLST in ste −/− mutant zebrafish since translation of DLST is predicted to be prematurely terminated and significant nonsense mediated RNA decay of the mutated dlst transcript is observed in ste −/− mutants.

Disorganization of the mitochondrial inner membrane and deranged architecture of cristae are common in human disorders featuring mitochondrial dysfunction [51]. Deficiency of the citric acid cycle is known to increase production of free radicals thereby inducing mitochondrial damage [35]. Similar to the situation in humans [25], we find severe alterations in mitochondrial morphology in the hearts and skeletal muscle of ste −/− mutants with disorganization and increased mitochondrial density as well as vacuoles within mitochondria and in their vicinity. The ste −/− mitochondria exhibit an irregularly shape with reduced cristae.

Interestingly, in a retrospective analysis of 90 patients with inherited mitochondriopathies, 22.2 % exhibited cardiac arrhythmias including sinus bradycardia [49]. ATP levels are significantly reduced in ste −/− mutants to one-third of the ATP content of wild-type zebrafish embryos. In the DLST-deficient ste −/− mutant embryos ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation is supposedly disrupted. However, ATP can usually also be produced by alternative pathways such as anaerobic glycolysis [14]. Furthermore, ATP can be provided by maternally inherited mitochondria. Similar to the situation in humans, maternal inheritance of the mitochondrial DNA and passing on of thousands of functionally active maternal mitochondria to the embryo warrants oxidative phosphorylation during zebrafish embryogenesis [3, 16, 41, 50]. Interestingly, bradycardia in the ste −/− mutant zebrafish is first present at 72 hpf. At earlier developmental stages, we find no significantly reduced heart rates in ste −/− mutant embryos, suggesting that at these stages the residual ATP production supposedly by maternal mitochondria is still sufficient to maintain a normal heart rate.

There are three different possibilities how these reduced ATP levels in ste −/− mutants might lead to bradycardia. Reduced ATP levels could either impact on: (1) myofilament activation, (2) excitability of the working myocardium or (3) the depolarization of cardiac pacemaker cells. However, we find here by external electrical stimulation experiments and calcium transient analyses that bradycardia in ste −/− mutants is not caused by prolonged refractoriness of cardiomyocytes to excitation, or by uncoupling of cardiomyocyte excitation–contraction, but rather by reduced firing rates of the cardiac pacemaker cells.

The pacemaker site of the zebrafish heart is localized in the right dorsal quadrant of the atrium, near the inflow tract of the atrium and the sinus venosus [2]. Tessadori et al. [44] demonstrated that the pacemaker cells in zebrafish resemble those in mammals in their gene expression pattern and electrochemical properties, in particular their ability to spontaneously depolarize. In mammals, a variety of regulatory mechanisms exist to influence the action potential frequency in sinus node cells [40, 48]. Pacemaker cells in mammals depend strongly upon ATP to function and to regulate their activity [48]. Yaniv et al. [48] recently demonstrated that in pacemaker cells the ATP supply is closely matched to the demand and is rapidly adjusted in phases of high ATP demand. ATP is necessary for the regulation of the action potential frequency in these cells via the Ca2+–calmodulin activated adenylyl cyclase/proteinkinase A, Ca2+–calmodulinkinase II, cAMP and Ca2+ pathways. The reduced ATP levels in ste −/− mutants are expected to impact on cAMP levels, since ATP is necessary to activate adenylyl cyclase to produce cAMP [48]. Interestingly, absence of cAMP in cardiac pacemaker cells is known to cause sinus bradycardia in mammals [40]. However, regular mitochondrial function not only warrants ATP production and enables consecutive pathways such as the cAMP/Ca2+ pathway, but is also crucial for various other essential mechanisms and metabolic pathways in mammals [1, 13]. Therefore, other ATP-independent mechanisms apart from reduced ATP levels might partially contribute to cardiac dysfunction in ste −/− mutant zebrafish embryos, since the ste −/− mutants’ mitochondrial function and structure is severely disrupted. Mitochondria are both an essential source of ROS as well as an important target of injury by ROS [25, 39]. Therefore, mitochondriopathies are often accompanied by enhanced ROS production causing further mitochondrial damage and leading to cell damage and inducing apoptosis [25, 39]. Similarly, increased ROS production and its consecutive injury to cells due to loss of mitochondrial DLST function possibly contribute to cardiac dysfunction in ste −/− mutants and thereby impact on heart rate regulation.

In search for novel genetic heart rate regulators den Hoed and co-workers recently conducted a GWAS meta-analysis and linked 14 chromosomal loci to heart rate regulation [12]. Interestingly, one of the associated loci contains DLST. Hence, thorough genetic analysis might reveal a modifying or even causal role of DLST gene variants in the pathogenesis of cardiac pacemaker diseases, such as the sick sinus syndrome.

References

Abel ED, Doenst T (2011) Mitochondrial adaptations to physiological vs. pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 90:234–242. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvr015

Arrenberg AB, Stainier DY, Baier H, Huisken J (2010) Optogenetic control of cardiac function. Science 330:971–974. doi:10.1126/science.1195929

Artuso L, Romano A, Verri T, Domenichini A, Argenton F, Santorelli FM, Petruzzella V (2012) Mitochondrial DNA metabolism in early development of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Biochim Biophys Acta 1817:1002–1011. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.03.019

Benson DW, Wang DW, Dyment M, Knilans TK, Fish FA, Strieper MJ, Rhodes TH, George AL Jr (2003) Congenital sick sinus syndrome caused by recessive mutations in the cardiac sodium channel gene (SCN5A). J Clin Invest 112:1019–1028. doi:10.1172/JCI18062

Bonnefont JP, Chretien D, Rustin P, Robinson B, Vassault A, Aupetit J, Charpentier C, Rabier D, Saudubray JM, Munnich A (1992) Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase deficiency presenting as congenital lactic acidosis. J Pediatr 121:255–258

Briere JJ, Schlemmer D, Chretien D, Rustin P (2004) Quinone analogues regulate mitochondrial substrate competitive oxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 316:1138–1142. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.002

Bugger H, Schwarzer M, Chen D, Schrepper A, Amorim PA, Schoepe M, Nguyen TD, Mohr FW, Khalimonchuk O, Weimer BC, Doenst T (2010) Proteomic remodelling of mitochondrial oxidative pathways in pressure overload-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 85:376–384. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvp344

Caldeira da Silva CC, Cerqueira FM, Barbosa LF, Medeiros MH, Kowaltowski AJ (2008) Mild mitochondrial uncoupling in mice affects energy metabolism, redox balance and longevity. Aging Cell 7:552–560. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00407.x

Crawford RB, Wilde CE Jr (1966) Cellular differentiation in the anamniota. II. Oxygen dependency and energetics requirements during early development of teleosts and urodeles. Exp Cell Res 44:453–470

Dahme T, Katus HA, Rottbauer W (2009) Fishing for the genetic basis of cardiovascular disease. Dis Model Mech 2:18–22. doi:10.1242/dmm.000687

Dalageorgou C, Ge D, Jamshidi Y, Nolte IM, Riese H, Savelieva I, Carter ND, Spector TD, Snieder H (2008) Heritability of QT interval: how much is explained by genes for resting heart rate? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 19:386–391. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01030.x

den Hoed M, Eijgelsheim M, Esko T, Brundel BJ, Peal DS, Evans DM, Nolte IM, Segre AV, Holm H, Handsaker RE, Westra HJ, Johnson T, Isaacs A, Yang J, Lundby A, Zhao JH, Kim YJ, Go MJ, Almgren P, Bochud M, Boucher G, Cornelis MC, Gudbjartsson D, Hadley D, van der Harst P, Hayward C, den Heijer M, Igl W, Jackson AU, Kutalik Z, Luan J, Kemp JP, Kristiansson K, Ladenvall C, Lorentzon M, Montasser ME, Njajou OT, O’Reilly PF, Padmanabhan S, St Pourcain B, Rankinen T, Salo P, Tanaka T, Timpson NJ, Vitart V, Waite L, Wheeler W, Zhang W, Draisma HH, Feitosa MF, Kerr KF, Lind PA, Mihailov E, Onland-Moret NC, Song C, Weedon MN, Xie W, Yengo L, Absher D, Albert CM, Alonso A, Arking DE, de Bakker PI, Balkau B, Barlassina C, Benaglio P, Bis JC, Bouatia-Naji N, Brage S, Chanock SJ, Chines PS, Chung M, Darbar D, Dina C, Dorr M, Elliott P, Felix SB, Fischer K, Fuchsberger C, de Geus EJ, Goyette P, Gudnason V, Harris TB, Hartikainen AL, Havulinna AS, Heckbert SR, Hicks AA, Hofman A, Holewijn S, Hoogstra-Berends F, Hottenga JJ, Jensen MK, Johansson A, Junttila J, Kaab S, Kanon B, Ketkar S, Khaw KT, Knowles JW, Kooner AS, Kors JA, Kumari M, Milani L, Laiho P, Lakatta EG, Langenberg C, Leusink M, Liu Y, Luben RN, Lunetta KL, Lynch SN, Markus MR, Marques-Vidal P, Mateo Leach I, McArdle WL, McCarroll SA, Medland SE, Miller KA, Montgomery GW, Morrison AC, Müller-Nurasyid M, Navarro P, Nelis M, O’Connell JR, O’Donnell CJ, Ong KK, Newman AB, Peters A, Polasek O, Pouta A, Pramstaller PP, Psaty BM, Rao DC, Ring SM, Rossin EJ, Rudan D, Sanna S, Scott RA, Sehmi JS, Sharp S, Shin JT, Singleton AB, Smith AV, Soranzo N, Spector TD, Stewart C, Stringham HM, Tarasov KV, Uitterlinden AG, Vandenput L, Hwang SJ, Whitfield JB, Wijmenga C, Wild SH, Willemsen G, Wilson JF, Witteman JC, Wong A, Wong Q, Jamshidi Y, Zitting P, Boer JM, Boomsma DI, Borecki IB, van Duijn CM, Ekelund U, Forouhi NG, Froguel P, Hingorani A, Ingelsson E, Kivimaki M, Kronmal RA, Kuh D, Lind L, Martin NG, Oostra BA, Pedersen NL, Quertermous T, Rotter JI, van der Schouw YT, Verschuren WM, Walker M, Albanes D, Arnar DO, Assimes TL, Bandinelli S, Boehnke M, de Boer RA, Bouchard C, Caulfield WL, Chambers JC, Curhan G, Cusi D, Eriksson J, Ferrucci L, van Gilst WH, Glorioso N, de Graaf J, Groop L, Gyllensten U, Hsueh WC, Hu FB, Huikuri HV, Hunter DJ, Iribarren C, Isomaa B, Jarvelin MR, Jula A, Kähönen M, Kiemeney LA, van der Klauw MM, Kooner JS, Kraft P, Iacoviello L, Lehtimäki T, Lokki ML, Mitchell BD, Navis G, Nieminen MS, Ohlsson C, Poulter NR, Qi L, Raitakari OT, Rimm EB, Rioux JD, Rizzi F, Rudan I, Salomaa V, Sever PS, Shields DC, Shuldiner AR, Sinisalo J, Stanton AV, Stolk RP, Strachan DP, Tardif JC, Thorsteinsdottir U, Tuomilehto J, van Veldhuisen DJ, Virtamo J, Viikari J, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Widen E, Cho YS, Olsen JV, Visscher PM, Willer C, Franke L; Global BPgen Consortium; CARDIoGRAM Consortium, Erdmann J, Thompson JR; PR GWAS Consortium, Pfeufer A; QRS GWAS Consortium, Sotoodehnia N; QT-IGC Consortium, Newton-Cheh C; CHARGE-AF Consortium, Ellinor PT, Stricker BH, Metspalu A, Perola M, Beckmann JS, Smith GD, Stefansson K, Wareham NJ, Munroe PB, Sibon OC, Milan DJ, Snieder H, Samani NJ, Loos RJ (2013) Identification of heart rate-associated loci and their effects on cardiac conduction and rhythm disorders. Nat Genet 45:621–631 doi:10.1038/ng.2610

Di Donato S (2009) Multisystem manifestations of mitochondrial disorders. J Neurol 256:693–710. doi:10.1007/s00415-009-5028-3

Doenst T, Nguyen TD, Abel ED (2013) Cardiac metabolism in heart failure: implications beyond ATP production. Circ Res 113:709–724. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300376

Ebert AM, Hume GL, Warren KS, Cook NP, Burns CG, Mohideen MA, Siegal G, Yelon D, Fishman MC, Garrity DM (2005) Calcium extrusion is critical for cardiac morphogenesis and rhythm in embryonic zebrafish hearts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:17705–17710. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502683102

Farrar GJ, Chadderton N, Kenna PF, Millington-Ward S (2013) Mitochondrial disorders: aetiologies, models systems, and candidate therapies. Trends Genet 29:488–497. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2013.05.005

Gibbs CL (1978) Cardiac energetics. Physiol Rev 58:174–254

Guffon N, Lopez-Mediavilla C, Dumoulin R, Mousson B, Godinot C, Carrier H, Collombet JM, Divry P, Mathieu M, Guibaud P (1993) 2-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase deficiency, a rare cause of primary hyperlactataemia: report of a new case. J Inherit Metab Dis 16:821–830

Haefeli RH, Erb M, Gemperli AC, Robay D, Courdier Fruh I, Anklin C, Dallmann R, Gueven N (2011) NQO1-dependent redox cycling of idebenone: effects on cellular redox potential and energy levels. PLoS ONE 6:e17963. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017963

Hassel D, Scholz EP, Trano N, Friedrich O, Just S, Meder B, Weiss DL, Zitron E, Marquart S, Vogel B, Karle CA, Seemann G, Fishman MC, Katus HA, Rottbauer W (2008) Deficient zebrafish ether-a-go-go-related gene channel gating causes short-QT syndrome in zebrafish reggae mutants. Circulation 117:866–875. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.752220

Hoffmann S, Berger IM, Glaser A, Bacon C, Li L, Gretz N, Steinbeisser H, Rottbauer W, Just S, Rappold G (2013) Islet1 is a direct transcriptional target of the homeodomain transcription factor Shox2 and rescues the Shox2-mediated bradycardia. Basic Res Cardiol 108:339. doi:10.1007/s00395-013-0339-z

Jowett T, Lettice L (1994) Whole-mount in situ hybridizations on zebrafish embryos using a mixture of digoxigenin- and fluorescein-labelled probes. Trends Genet 10:73–74

Just S, Meder B, Berger IM, Etard C, Trano N, Patzel E, Hassel D, Marquart S, Dahme T, Vogel B, Fishman MC, Katus HA, Strahle U, Rottbauer W (2011) The myosin-interacting protein SMYD1 is essential for sarcomere organization. J Cell Sci 124:3127–3136. doi:10.1242/jcs.084772

Kessler M, Just S, Rottbauer W (2012) Ion flux dependent and independent functions of ion channels in the vertebrate heart: lessons learned from zebrafish. Stem Cells Int 2012:462161. doi:10.1155/2012/462161

Knowlton AA, Chen L, Malik ZA (2013) Heart failure and mitochondrial dysfunction: the role of mitochondrial fission/fusion abnormalities and new therapeutic strategies. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. doi:10.1097/01.fjc.0000432861.55968.a6

Kohlschutter A, Behbehani A, Langenbeck U, Albani M, Heidemann P, Hoffmann G, Kleineke J, Lehnert W, Wendel U (1982) A familial progressive neurodegenerative disease with 2-oxoglutaric aciduria. Eur J Pediatr 138:32–37

Kusumoto FM, Goldschlager N (1996) Cardiac pacing. N Engl J Med 334:89–97. doi:10.1056/NEJM199601113340206

Langenbacher AD, Dong Y, Shu X, Choi J, Nicoll DA, Goldhaber JI, Philipson KD, Chen JN (2005) Mutation in sodium-calcium exchanger 1 (NCX1) causes cardiac fibrillation in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:17699–17704. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502679102

Makky K, Duvnjak P, Pramanik K, Ramchandran R, Mayer AN (2008) A whole-animal microplate assay for metabolic rate using zebrafish. J Biomol Screen 13:960–967. doi:10.1177/1087057108326080

Mastrogiacomo F, Bergeron C, Kish SJ (1993) Brain α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex activity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 61:2007–2014. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07436.x

Meder B, Scholz EP, Hassel D, Wolff C, Just S, Berger IM, Patzel E, Karle C, Katus HA, Rottbauer W (2011) Reconstitution of defective protein trafficking rescues Long-QT syndrome in zebrafish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 408:218–224. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.121

Mendelsohn BA, Kassebaum BL, Gitlin JD (2008) The zebrafish embryo as a dynamic model of anoxia tolerance. Dev Dyn 237:1780–1788. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21581

Michelmore RW, Paran I, Kesseli RV (1991) Identification of markers linked to disease-resistance genes by bulked segregant analysis: a rapid method to detect markers in specific genomic regions by using segregating populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:9828–9832

Pelster B, Burggren WW (1996) Disruption of hemoglobin oxygen transport does not impact oxygen-dependent physiological processes in developing embryos of zebra fish (Danio rerio). Circ Res 79:358–362

Pieczenik SR, Neustadt J (2007) Mitochondrial dysfunction and molecular pathways of disease. Exp Mol Pathol 83:84–92. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2006.09.008

Proudfoot AT, Bradberry SM, Vale JA (2006) Sodium fluoroacetate poisoning. Toxicol Rev 25:213–219

Rottbauer W, Baker K, Wo ZG, Mohideen MA, Cantiello HF, Fishman MC (2001) Growth and function of the embryonic heart depend upon the cardiac-specific L-type calcium channel alpha1 subunit. Dev Cell 1:265–275

Russell MW, Law I, Sholinsky P, Fabsitz RR (1998) Heritability of ECG measurements in adult male twins. J Electrocardiol 30(Suppl):64–68

Schwarzer M, Osterholt M, Lunkenbein A, Schrepper A, Amorim P, Doenst T (2014) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production and respiratory complex activity in rats with pressure overload-induced heart failure. J Physiol 592:3767–3782. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.274704

Schweizer PA, Duhme N, Thomas D, Becker R, Zehelein J, Draguhn A, Bruehl C, Katus HA, Koenen M (2010) cAMP sensitivity of HCN pacemaker channels determines basal heart rate but is not critical for autonomic rate control. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 3:542–552. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.110.949768

Shoubridge EA, Wai T (2007) Mitochondrial DNA and the mammalian oocyte. Curr Top Dev Biol 77:87–111. doi:10.1016/S0070-2153(06)77004-1

Stainier DY, Fishman MC (1994) The zebrafish as a model system to study cardiovascular development. Trends Cardiovasc Med 4:207–212. doi:10.1016/1050-1738(94)90036-1

Suga H (1990) Ventricular energetics. Physiol Rev 70:247–277

Tessadori F, van Weerd JH, Burkhard SB, Verkerk AO, de Pater E, Boukens BJ, Vink A, Christoffels VM, Bakkers J (2012) Identification and functional characterization of cardiac pacemaker cells in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 7:e47644. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047644

Tokoro T, Ito H, Maenishi O, Suzuki T (1995) Mitochondrial abnormalities in hypertrophied myocardium of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl 22:S268–269

Wellner-Kienitz MC, Bender K, Rinne A, Pott L (2004) Voltage dependence of ATP-dependent K+ current in rat cardiac myocytes is affected by IK1 and IK(ACh). J Physiol 561:459–469. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.073197

Westerfield M (1993) The zebrafish book; a guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio). University of Oregon Press, Eugene

Yaniv Y, Spurgeon HA, Ziman BD, Lyashkov AE, Lakatta EG (2013) Mechanisms that match ATP supply to demand in cardiac pacemaker cells during high ATP demand. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304:H1428–1438. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00969.2012

Zhang LH, Fang LG, Cheng ZW, Fang Q (2009) Cardiac manifestations of patients with mitochondrial disease. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 37:892–895

Zhang YZ, Ouyang YC, Hou Y, Schatten H, Chen DY, Sun QY (2008) Mitochondrial behavior during oogenesis in zebrafish: a confocal microscopy analysis. Dev Growth Differ 50:189–201. doi:10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.00988.x

Zick M, Rabl R, Reichert AS (2009) Cristae formation-linking ultrastructure and function of mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793:5–19. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.06.013

Acknowledgments

We thank Regine Baur, Karen Frese, Kristin Haugg, Sabine Marquart, and Jessica Rudloff for their excellent technical assistance. We acknowledge the Tübingen 2000 Screen Consortium (Max-Planck-Institut für Entwicklungsbiologie, Tübingen: Bebber van, F., Busch-Nentwich, E., Dahm, R., Frohnhöfer, H.-G., Geiger, H., Gilmour, D., Holley, S., Hooge, J., Jülich, D., Knaut, H., Maderspacher, F., Neumann, C., Nicolson, T., Nüsslein-Volhard, C., Roehl, H., Schönberger, U., Seiler, C., Söllner, C., Sonawane, M., Wehner, A., and Weiler, C.) and Exelixis Deutschland GmbH (Erker, P.; Habeck, H.; Hagner, U., Hennen, E., Kaps, C., Kirchner, A., Koblizek, T.I., Langheinrich, U., Loeschke, C; Metzger, C., Nordin, R., Loeschke, C.; Pezzuti, M., Schlombs, K., deSantana-Stamm, J., Trowe, T., Vacun, G., Walderich, B.; Walker, A., and Weiler, C.) for carrying out the ENU-mutagenesis-screen and providing the zebrafish mutant line. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) RO2173/4-1, RO2173/4-2, JU2859/1-2, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung 01GS1104 (NGFNplus), 01KU0901C (Insight-DCM), Hertha-Nathorff-Scholarship and the European Union (Inheritance).

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

S. Just and W. Rottbauer contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

395_2015_468_MOESM1_ESM.tiff

Supplementary Fig. 1 Human and zebrafish DLST are highly homologous. Amino acid sequence alignment of human (hdlst), zebrafish (zdlst) and ste −/− mutant DLST. Human and zebrafish DLST share 74 % amino acid identity. The highly conserved lipoyl and catalytic domains are indicated with red lines above the alignment (TIFF 485 kb)

Supplementary Movie Electrical stimulation of a ste −/− mutant heart at 72 hpf. ste −/− mutants were injected with fluorescent dye to monitor free cytosolic myocardial calcium and cardiac contraction simultaneously. Electrical stimulation drives up basal heart rate of ste −/− mutants to normofrequency and leads to sequential and coordinated contractions of atrium and ventricle (MPG 7736 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Keßler, M., Berger, I.M., Just, S. et al. Loss of dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase (DLST) leads to reduced resting heart rate in the zebrafish. Basic Res Cardiol 110, 14 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-015-0468-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-015-0468-7