Abstract

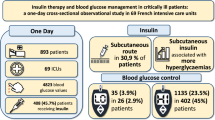

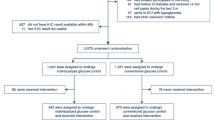

The VISEP study was conducted in a randomized manner from April 2003 to June 2005 in 18 interdisciplinary intensive care units. Two questions were to be clarified: (1) Is the benefit of intensive insulin therapy reproducible in septic patients and (2) should crystalloids or colloids be used for initial fluid resuscitation in severe sepsis? A total of 2212 patients were screened, but only 600 patients were randomized into the four study groups. Intensive insulin therapy The blood glucose level was adjusted to be between 80 and 110 mg/dl in the intensive insulin therapy (IIT) group and between 180 and 200 mg/dl in the “conservative” insulin group (CIT). There were no significant differences in mortality at day 28 and day 90 (24.7 vs 26.0%; p = 0.74 and 39.7 vs 35.4%; p = 0.31, respectively). Indeed, the study had to be stopped because of safety reasons due to significantly more serious hypoglycemic states (17.0 vs 4.1%; p < 0.001) in the IIT group. Although the study does not refute the benefit of intensive insulin therapy, the results will contribute to the end of IIT in intensive care units. Colloids vs crystalloids A total of 600 patients were randomized, but only 262 patients were treated by 10% HES 200/0.5 and 303 by Ringer’s lactate (Sterofundin®). At day 28, the mortality was insignificantly increased in the HES group compared with the Ringer’s lactate group (26.7 vs 24.1%; p = 0.48). At day 90, a significantly increased mortality was observed in the HES group (26.7 vs 24.1%; p = 0.48). In addition, a significantly increased incidence of acute renal failure (34.9 vs 22.8%; p = 0.02) was seen and renal replacement therapy became necessary more frequently (18.3 vs 9.2%). For these reasons, the authors warn about the use of hydroxyethyl starch in severe sepsis and septic shock. The submitted data do not justify this warning. The daily maximal dose of 20 ml/ kg/d for 10% HES 200/0.5 was exceeded and the recommended upper serum creatinine level was elevated from 177 to 320 µmol/l. For patients treated with recommended daily dosage of 20 ml/kg/ d (22 mg/kg/d in the study), the mortality is comparable with Ringer’s lactate at days 28 and 90 (22.8 vs 24.1%; p = 0.747 and 30.9 vs 33.9%; p = 0.562, respectively). The study has shown that 10% HES 200/0.5 is a drug, for which the indication, contraindications and daily maximal dose have to be met.

Zusammenfassung

Die VISEPStudie wurde zwischen April 2003 und Juni 2005 in 18 interdisziplinären Intensivstationen deutscher Krankenhäuser randomisiert durchgeführt, um 2 Fragen zu klären: (1) Lässt sich der Nutzen der intensiven Insulintherapie am septischen Patienten reproduzieren und (2) sollen Kristalloide oder Kolloide zur initialen Kreislaufstabilisierung bei schwerer Sepsis verwendet werden? Es wurden 2212 Patienten mit Sepsis ge screent, aber letztendlich nur 600 in die 4 Studienarme randomisiert. Intensive Insulintherapie In der Gruppe mit intensiver Insulintherapie (IIT) sollte der Blutzucker zwischen 80 und 110 mg/ dl und in der „konservativen“ Insulingruppe zwischen 180 und 200 mg/dl eingestellt werden. Es gab keine signifikanten Letalitätsunterschiede nach 28 bzw. 90 Tagen (24,7 vs. 26,0%; p = 0,74 bzw. 39,7 vs. 35,4%; p = 0,31). Die Studie wurde jedoch wegen signifikant häufigerer schwerer Hypoglykämien (17,0 vs. 4,1%; p < 0,001) in der IIT-Gruppe aus Sicherheitsgründen gestoppt. Damit steht die intensive Insulintherapie auf den Intensivstationen vor dem „Aus“, ihr Nutzen ist allerdings nicht schlüssig widerlegt worden. Kolloide vs. Kristalloide Es wurden 600 Patienten randomisiert und letztlich 262 mit 10% HES 200/0,5 und 303 mit Ringer- Laktat (Sterofundin®) behandelt. Die HES- Gruppe wies gegenüber der Ringer-Laktat-Gruppe eine nichtsignifikant erhöhte 28-Tage- Letalität (26,7 vs. 24,1%; p = 0,48), aber eine signifikant erhöhte 90- Tage-Letalität auf (41,0 vs. 33,9%; p = 0,09). In der HES-Gruppe fand sich eine signifikant höhere Rate von akutem Nierenversagen (34,9 vs. 22,8%; p = 0,002) und mehr Nierenersatztherapie (18,3 vs. 9,2%). Daraus leiten die Autoren die Schlussfolgerung ab, vor der Therapie mit Hydroxyäthylstärke bei schwerer Sepsis und septischem Schock warnen zu müssen. Nach den vorliegenden Daten ist das nicht gerechtfertigt. Die Tagesmaximaldosis von 20 ml/kg/d für 10% HES 200/0,5 wurde überschritten und der empfohlene obere Serumkreatininwert von 177 _mol/l in der Studie auf maximale 320 µmol/l angehoben. Bei Einhalten der empfohlenen maximalen HES-Dosis pro Tag von 20 ml/kg Körpermasse (in der Studie wurden 22 ml/kg/d zugrunde gelegt) ergibt sich eine dem Ringer-Laktat vergleichbare 28- und 90 Tage-Letalität (22,8 vs. 24,1%; p = 0,747 bzw. 30,9 vs. 33,9%; p = 0,562). Die Studie hat lediglich belegt, dass die 10% HES 200/0,5 ein Medikament ist, für das Indikationen, Kontraindikationen und Tagesmaximaldosierungen einzuhalten sind.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literatur

Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F et al (2001) Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 345:1359–1367

Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G et al (2006) Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med 354:449–461

Van den Berghe G, Wouters PJ, Bouillon R et al (2003) Outcome benefit of intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill: insulin dose versus glycemic control. Crit Care Med 31:359–366

Ellger B, Westphal M, Stubbe H et al (2008) Blutzuckerkontrolle bei Patienten mit Sepsis und septischem Schock – Freund oder Feind? Anästhesist 57:43–48

Krinsley JS (2004) Effect of an intensive glucose management protocol on the mortality of critically ill adult patients. Mayo Clin Proc 79:992–1000

Christiansen C, Toft P, Jorgensen HS et al (2004) Hyperglycaemia and mortality in critically ill patients. A prospective study. Intensive Care Med 30:1685–1688

Kanji S, Singh A, Tierney M et al (2004) Standardization of intravenous insulin therapy improves the efficiency and safety of blood glucose control in critically ill adults. Intensive Care Med 30:804–810

Meijering S, Corstjens AM, Tulleken JE et al (2006) Towards a feasible algorithm for tight glycaemic control in critically ill patients: a systematic review of the literature. Critical Care 10:R19

Barclay L, Vega C, Martin BN (2008) Intensive insulin therapy may protect renal function in critically ill patients. J Am Soc Nephrol, published online January 30

Asakawa H, Miyagawa JI, Hanafusa T et al (1997) High glucose and hyperosmolarity increase secretion of interleukin- 1β in cultured human aortic endothelial cells. J Diab Comp 11:176–179

Nemeth ZH, Deitch EA, Szabo C, Hasko G (2002) Hyperosmotic stress induces nuclear factor-κB activation and interleukin-8 production in human intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Pathol 161:877–996

Perner A, Nielsen SE, Rask-Madsen J (2003) High glucose impairs superoxide production from isolated blood neutrophils. Intensive Care Med 29:642–645

McGinn S, Poronnik P, King M et al (2003) High glucose and endothelial cell growth: novel effects independent of autocrine TGF-β1 and hyperosmolarity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284:C1374–C1386

Marik PE, Raghavan M (2004) Stresshyperglycemia, insulin and immunomodulation in sepsis. Intensive Care Med 30:748–756

Van den Berghe G (2004) How does blood glucose control with insulin save lives in intensive care? J Clin Invest 114:1187–1195

Jeschke MG, Klein D, Herndon DN (2004) Insulin treatment improves the systemic inflammatory reaction to severe trauma. Ann Surg 239:553–560

Dandona P, Mohanty P, Chaudhuri A et al (2005) Insulin infusion in acute illness. J Clin Invest 115:2069–2072

Langouche L, Vanhorebeek I, Vlasserelaers D, Perre SV et al (2005) Intensive insulin therapy protects the endothelium of critically ill patients. J Clin Invest 115:2277–2286

Dandona P, Aljada A, Mohanty P et al (2001) Insulin inhibits intranuclear nuclear factor _B and stimulates IκB in mononuclear cells in obese subjects: evidence for an anti-inflammatory effect? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:3257–3265

Zander R, Boldt J, Engelmann L et al (2007) Studienprotokoll der VISEPStudie. Eine kritische Stellungnahme. Anästhesist 56:71–77

Brunkhorst FM, Werdan K (2006) Intensivmedizin – Nach den positiven Studien kommen die Fragen. Dtsch med Wochenschr 131:1441–1444

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S et al (2001) Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 345:1368–1377

Köhler H, Zschiedrich H, Clasen R et al (1982) Blutvolumen, kolloidosmotischer Druck und Nierenfunktion von Probanden nach Infusion mittelmolekularer 10% Hydroxyäthylstärke 200/0,5 und 10% Dextran 40. Anästhesist 31:61–67

Reinhart K (2006) Fluid therapy in sepsis – VISEP study results (SepNet). Symposium Intensivmedizin, Bremen

Lehmann GB, Asskali F, Boll M et al (2007) HES 130/0,42 shows less alteration of pharmacokinetics than HES 200/0.5 when dosed repeatedly. Br J Anaesth 98:635–644

Schortgen F, Lacherade JC, Bruneel F et al (2001) Effects of hydroxyethylstarch and gelatin on renal function in severe sepsis: a multicentre randomized study. Lancet 357:911–916

Wiedermann CJ (2004) Hydroxyethyl starch – can the safety problem be ignored? Wien Klin Wochenschr 116/ 17/18:583–594

Boldt J, Brosch C, Ducke M et al (2007) Influence of volume therapy with modern hydroxyethylstarch preparation on kidney function in cardiac surgery patients with compromised renal function: a comparison with human albumin. Crit Care Med 35:2740–2746

Sakr Y, Payen D, Reinhart K et al (2007) Effects of hydroxyethyl starch administration on renal function in critically ill patients. Br J Anaesth 98:216–224

Brunkhorst FM, Schortgen F, Sakr Y, Vincent JL (2007) Effects of hydroxyethyl starch in critically ill patients. Br J Anaesth 98:842–844

Lang W (2007) Treffpunkt Stewart. Pufferbasen, „base excess“ und starke Ionen. Anästhesist 56:388–397

Adams HA (2007) Hämodilution und Infusionstherapie bei hypovolämischen Schock. Anästhesist 56:371–379

Kellum JA, Song M, Almasri E (2006) Hyperchloremic acidosis increases circulating inflammatory molecules in experimental sepsis. CHEST 130:962–967

Hoffmann JN, Vollmar B, Laschke MW et al (2002) Hydroxyethyl starch (130 kD), but not crystalloid volume support, improves microcirculation during normotensive endotoxemia. Anaesthesiology 97:460–470

Collis RE, Collins PW, Gutteridge CN et al (1994) The effect of hydroxyethyl starch and other plasma volume substitutes on endothelial cell activation; an in vitro study. Intensive Care Med 20:37–41

Boldt J (2006) Do plasma substitutes have additional properties beyond correcting volume deficits? SHOCK 25:103–116

Dieterich HJ, Weissmüller T, Rosenberger P, Eltzschig HK (2006) Effect of hydroxyethyl starch on vascular leak syndrome and neutrophil accumulation during hypoxia. Crit Care Med 34:1775–1782

Dieterich HJ, Nohe B, Drescher N et al (1998) Modulation von Phagozytose und Endothelfunktion. Anästhesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 33:270–274

Boldt J, Müller M, Menges T et al (1996) Influence of different volume therapy regimens on regulators of the circulation in the critically ill. Br J Anaesth 77:480–487

Hofbauer R, Moser D, Hornykiewicz S et al (1999) Hydroxyethyl starch reduces the chemotaxis of white cells through endothelial cell monolayers. Transfusion 39:289–294

Schmand JF, Ayala A, Morrison MH, Chaudry IH (1995) Effects of hydroxyethyl starch after trauma-hemorrhagic shock: restoration of macrophage integrity and prevention of increased circulating interleukin-6 levels. Crit Care Med 23:806–814

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Engelmann, L. Die VISEP-Studie: ein Schritt vorwärts, zwei Schritte zurück. Intensivmed 45, 255–262 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00390-008-0887-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00390-008-0887-x

Key words

- severe sepsis

- septic shock

- intensive insulin therapy

- hypoglycemia

- volume resuscitation

- hydroxyethyl starch

- Ringer’s lactate

- mortality

- renal failure