Abstract

We consider the problem of dividing a perfectly divisible good among individuals who have other-regarding preferences. Assuming no legitimate claims and purely ordinal preferences, how should society measure social welfare so as to satisfy basic principles of efficiency and fairness? In a simple model of average externalities, we characterize the class of social preferences which give full priority to the individual with the lowest egalitarian equivalent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The small existing literature on fairness and externalities focuses on allocation rules (Villar 1988; Nieto 1991; Kolm 1995; Velez 2016). Only Decerf and Van der Linden (2016) follow the same approach as this paper. They investigate the problem of defining fair social orderings for the allocation of multiple goods on a domain of preferences that exclude altruistic preferences. However, their more general framework does not allow for characterization results.

Defining such a comprehensive measure of social welfare is essential when the subset of feasible allocations is limited or uncertain, which may happen in particular if the social planner has to respect different types of legal, political or informational constraints. The approach has been applied to many different issues, including the fair allocation of multiple divisible goods (Fleurbaey 2005, 2007; Fleurbaey and Maniquet 2008), public goods ( Maniquet and Sprumont 2004, 2005) or indivisible goods (Maniquet 2008). It has also been used for the evaluation of income tax schedules (Fleurbaey and Maniquet 2006) and the comparison of allocations for populations of different sizes and preferences (Fleurbaey and Tadenuma 2014).

Throughout the paper we use the term consumption to refer to the amount allocated to each individual.

A weaker requirement would be that for any allocation x in \(\mathbb {R}_{+}^N\), and any \(\delta \in ]0,x_i]\), there exists \(\lambda >\frac{\delta }{n-1}\) such that \(\displaystyle { x\;P_i\;\left( x_i-\delta ,(x_j + \lambda )_{j\ne i}\right) }\). When combined with all of our other requirements, this weaker axiom allows for indifference curves (see description of the consumption space below) with a slope in \(]0,\frac{n-2}{n}]\), which are forbidden under the original axiom. While we believe that a similar characterization result as Theorem 1 could be obtained with that weaker version of Bounded Altruism, we stick to the original version for simplicity.

Alternatively, we could assume individuals care about the average consumption in the rest of the economy \(\bar{x}_{-i}=\sum _{k \ne i} x_k \slash (n-1)\). While the two assumptions are formally equivalent (they define the same subdomain of preferences), the choice of focusing on the average consumption is not totally innocuous as the axioms and properties we impose (which refer to the average consumption) would have different implications if they were to refer instead to the average consumption in the rest of the economy \(\bar{x}_{-i}\).

We also abuse notation by sometimes comparing allocations \(x\in \mathbb {R}_+^N\) with bundles \((x_i,\bar{x})\in \mathbb {R}_{+}^2\).

See the appendix for a formal definition of these two monotonicity properties and a proof of the implications.

Note, however, that on \(\mathcal {R}_A\), if the egalitarian equivalent exists then it is necessarily unique.

Note that because of Preference for Positive Consumption and Continuity, the vertical axis must necessarily constitute an indifference curve.

Assume, by contradiction, that there exists two allocations x and y such that \(\bar{x}<\bar{y}\) and x Pareto dominates y. Let i be any individual in N. Then, because i must necessarily prefer x to y, Uniform Monotonicity means that \(y_i<x_i+(\bar{y}-\bar{x})\). However, this also implies that there exists at least one other individual j for which \(y_j>x_j+(\bar{y}-\bar{x})\). By Uniform Monotonicity again, j must prefer (strictly) y to x, a contradiction since x Pareto dominates y. For the same reason, two different allocations are never Pareto indifferent on \(\mathcal {R}_A\).

The standard Pigou-Dalton transfer principle used in the theory of inequality measurement (Pigou 1912) requires any transfer from some richer to some poorer individual (while preserving their relative order) to be considered a social improvement. It reflects a stronger form of resource egalitarianism than Transfer to Disadvantaged because it also applies to pairs of individuals who are either both advantaged or both disadvantaged. Note that in contrast with the classical setting, Transfer and Pareto are compatible on \(\mathcal {R}_A\). Consider for example R(.) such that \(xR(R_N)y\) iff \(\min _{i\in N}x_i+\bar{x}\ge \min _{i\in N}y_i+\bar{y}\).

In social choice, this requirement is generally referred to as Independence from Indifferent Individuals (Sen 1970).

Consider for example \(x\,{R}(R_N)\,y\) iff \(\bar{x}\ge \bar{y}\).

In the classical multi-dimensional setting, the closest axiom to Transfer to Disadvantaged would be Equal Split Transfer. Combining Strong Pareto, Unchange-Contour Independence and Equal-Split Transfer leads to Equal Split Priority (Fleurbaey and Maniquet 2011).

Whereby \(\min _N u_i(x,R_i)=\min _N u_i(y,R_i)\) implies \(x\;I(R_N)\;y\).

Other social ordering functions also satisfy all the requirements. One such example, as suggested in Fleurbaey and Maniquet (2011) (for a different context), consists in applying a different leximin social ordering to break possible ties in the original leximin social ordering function.

Where \(U_j(x,R_j)\) denotes the upper contour set of preference relation \(R_j\) at j’s consumption bundle \((x_j,\bar{x})\).

Otherwise, let \(B=\{i\in N \mid x_i\le \bar{x}\}\), \(a>\bar{x}\), and define allocation \(\tilde{x}\) such that:

$$\begin{aligned}&\tilde{x}_i=q_i(x,a,R_i) \;\;\forall i\in B\\&\tilde{x}_i=x_i+(a-\bar{x})+\frac{1}{n-\#B}\left( \sum _{j\in B}x_j+(a-\bar{x})-\tilde{x}_j\right) \;\;\forall i\not \in B \end{aligned}$$Note that \(\bar{\tilde{x}}=a\) and \(\tilde{x}_i\ne \bar{\tilde{x}}\) for all \(i\in N\). Since \(\tilde{x} I_i x\) for all \(i\in B\), Uniform Monotonicity implies \(x_i+(a-\bar{x})>\tilde{x}_i\) for all \(i\in B\). Therefore, \(\tilde{x}_i>x_i+(a-\bar{x})\) for all \(i\not \in B\), which by Uniform Monotonicity again, implies that \(\tilde{x} P_i x\) for all \(i\not \in B\). By Strong Pareto, we get that \(\tilde{x}P(R_N)x\). Since \(\min _{i\in N}u_i(\hat{x})=\min _{i\in N}u_i(x)<\min _{i\in N}u_i(y)\), and \(\tilde{x}_i\ne \bar{\tilde{x}}\) for all \(i\in N\), we can apply the proof of Theorem 1 (see below) to allocations \(\tilde{x}\) and y, which yields \(yP(R_N)\tilde{x}\). This finally implies \(yP(R_N)x\).

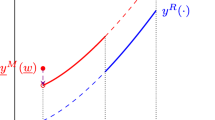

In all the figures below individual 3 refers to individual n in the proof.

References

Bolton GE, Ockenfels A (2000) ERC: a theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am Econ Rev 90(1):166–193

Charness G, Rabin M (2002) Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Q J Econ 117:817–869

Clark AE, Frijters P, Shields MA (2008) Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. J Econ Lit 46:95–144

Decerf B, Van der Linden M (2016) Fair social orderings with other-regarding preferences. Soc Choice Welf 46(3):655–694

Duesenberry J (1949) Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Easterlin R (1995) Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? J Econ Behav Organ 27:35–47

Fehr E, Schmidt KM (1999) A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Q J Econ 114:817–868

Fleurbaey M (2005) The Pazner-*Schmeidler social ordering: a defense. Rev Econ Design 9:145–166

Fleurbaey M (2007) Two criterias for social decisions. J Econ Theory 134:421–447

Fleurbaey M (2012) The importance of what people care about. Politics Philos Econ 11(4):415–447

Fleurbaey M, Maniquet F (2008) Fair social orderings. Econ Theor 34:25–45

Fleurbaey M, Maniquet F (2006) Fair Income Tax. Rev Econ Stud 73:55–83

Fleurbaey M, Maniquet F (2011) A theory of fairness and social welfare, econometric society monograph. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Fleurbaey M, Schokkaert E (2013) Behavioral Welfare Economics and Redistribution. Am Econ J Microecon 5(3):180–205

Fleurbaey M, Tadenuma K (2014) Universal social orderings: an integrated theory of policy evaluation, inter-society comparisons, and interpersonal comparisons. Rev Econ Stud 81:1071–1101

Fleurbaey M, Trannoy A (2003) The impossibility of a Paretian Egalitarian. Soc Choice Welf 21:243–263

Frank RH (1985) Positional externalities cause large and preventable welfare losses. Am Econ Rev 95(2):137–141

Frank RH (2005) Choosing the right pond. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gaertner W (2006) A primer in social choice theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Heath J (2006) Envy and Efficiency. Revue de philosophie économique 14:3–30

Kolm SC (1995) The economics of social sentiments: the case of envy. Jpn Econ Rev 46:63–87

Maniquet F (2008) Social orderings for the assignment of indivisible objects. J Econ Theory 143(1):199–215

Maniquet F, Sprumont Y (2004) Fair production and allocation of an excludable nonrival good. Econometrica 72(2):627–640

Maniquet F, Sprumont Y (2005) Welfare egalitarianism in non-rival environments. J Econ Theory 120:155–174

Moulin H (1992) Welfare bounds in the cooperative production problem. Games Econ Behav 4:373–401

Nieto J (1991) A note on Egalitarian and efficient allocations with externalities in consumption. J Public Econ 46:261–266

Pazner E, Schmeidler D (1978) Egalitarian equivalent allocations: a new concept of economic equity. Q J Econ 92:671–687

Pigou AC (1912) Wealth and welfare. Macmillan, London

Sen A (1970) Collective choice and social welfare. Holden Day, San Francisco

Sobel J (2005) Interdependent preferences and reciprocity. J Econ Lit 43(392):436

Sprumont Y (2012) Resource Egalitarianism with a dash of efficiency. J Econ Theory 147(1602):1613

Thomson W (2010) Fair allocation rules. In: Arrow K, Sen AK, Suzumura K (eds) Handbook of social choice and welfare volume II. North-Holland, Amsterdam, New York

Varian H (1974) Efficiency, equity and envy. J Econ Theory 9:63–91

Veblen T (1899) The theory of the leisure class. MacMillan, New York

Velez R (2016) Fairness with externalities. Theor Econ 11:381–410

Villar A (1988) On the existence of pareto optimal allocations when individual welfare depends on relative consumption. J Public Econ 36:387–397

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I am grateful to Marc Fleurbaey and Jean-François Laslier for their advice and suggestions, as well as two anonymous referees and the associate editor for very helpful remarks. I would also like to thank Benoit Decerf, Yukio Koriyama, Antonin Macé, François Maniquet, Stefan Napel, Lars Peter Østerdal, Eduardo Perez, Paolo Piacquadio, Yves Sprumont, Karol Szwagrzak, Giacomo Valletta and Martin Van der Linden.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Treibich, R. Welfare egalitarianism with other-regarding preferences. Soc Choice Welf 52, 1–28 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-018-1135-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-018-1135-3