Abstract

The investigation of flows at high Reynolds number is of great interest for the theory of turbulence, in that the large and the small scales of turbulence show a clear separation. But, as the Reynolds number of the flow increases, the size of the Kolmogorov length scale (\(\eta\)) drops almost proportionally. Aiming at achieving the adequate spatial resolution in the central region of a self-similar round jet at high Reynolds numbers (\(Re_\lambda \approx 350\)), a long-range μPIV system was applied. A vector spacing of \(1.5 \eta\) was achieved, where the Kolmogorov length scale was estimated to be \(55\,\upmu {\rm m}\). The resulting velocity fields were used to characterize the small-scale flow structures in this jet. The autocorrelation maps of vorticity and \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) (the imaginary part of the eigenvalue of the reduced velocity gradient tensor) reveal that the structures of intense vorticity have a characteristic diameter of approximately \(10 \eta\). From the autocorrelation map of the reduced (2D) rate of dissipation, it is inferred that the regions of intense dissipation tend to organize in the form of sheets with a characteristic thickness of approximately \(10 \eta\). The regions of intense dissipation have the tendency to appear in the vicinity of intense vortices. Furthermore, the joint pdf of the two invariants of the reduced velocity gradient tensor exhibits the characteristic teapot-shape. These results, based on a statistical analysis of the data, are in agreement with previous numerical and experimental studies at lower Reynolds number, which validates the suitability of long-range μPIV for characterizing turbulent flow structures at high Reynolds number.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The nature of the small-scale motions has received a renewed interest in the recent past, which is supported by datasets from DNS (Li et al. 2008; Ishihara et al. 2009), PIV (Ganapathisubramani et al. 2008), or even both simulations and experiments (Elsinga and Marusic 2010). The scaling of the small-scale motions and their topological content were in particular the two aspects which captured the interest mostly. In isotropic turbulence, the regions of intense vorticity were found to organize themselves in structures, shaped as elongated tubes (“worms”) (see Siggia 1981; Ashurst et al. 1987 among others). These “worm-like” structures were originally identified from DNS datasets. Their diameter was suggested to scale with the Kolmogorov length scale, whereas their length with the integral length scale of the flow, as proposed by Jimenez et al. (1993). Lately, Ganapathisubramani et al. (2008) observed experimentally that the fully-developed region of a jet was populated by similar “worm-like” structures, whose diameter was approximately ten Kolmogorov length scales (\(10 \eta\)), and whose length ranged from \(60\) to \(100\eta\). In the same work, it was also found that the clustering of the vortex tubes induces the formation of regions of intense dissipation, which are responsible for around 50 % of the total dissipation. These regions of intense dissipations tend to be located in the neighborhood of vortex tubes, and exhibit a sheet-like shape. Intense dissipation was observed adjacent to the intense vortices also in wall-bounded turbulence (Chacin and Cantwell 2000). In the turbulent boundary layers, the fine scales of turbulence were analogously found to form intense vortices. According to Herpin et al. (2013), the radius of these vortices does not depend on the Reynolds number and the wall distance when scaled with the local Kolmogorov length scale. The most probable size of the radius of the vortices was measured to be \(7 \eta\). Visual inspection of isosurfaces of vorticity amplitude led Ishihara et al. (2013) to estimate the thickness of the vortices to be approximately \(10 \eta\). Their simulations are of particular interest in that the Reynolds number of the flow based on the Taylor microscale was more than 1,131, a value never achieved in any earlier DNS study.

Furthermore, the local flow topology could be extracted through the analysis of the invariants of the velocity gradient tensor (Chong et al. 1990). Two aspects were found in the small-scale motions, independent of the turbulent flow under investigation. Firstly, the vorticity vector exhibits a preferential alignment with the eigenvector corresponding to the intermediate eigenvalue of the strain rate tensor (Lüthi et al. 2005; Ashurst et al. 1987). Secondly, the joint probability density function (p.d.f.) of the second and third invariant of the velocity gradient tensor, Q and R, presents a teardrop shape (Chong et al. 1998; Ooi et al. 1999; Soria et al. 1994). Recently, both these apparent universal aspects of small-scale topology were associated with the existence of dominant shear layer structures containing the vortices (Elsinga and Marusic 2010). From the experimental point of view, the described achievements were possible largely in consequence of the development of tomographic PIV (Elsinga et al. 2006) and cinematographic stereoscopic PIV (Ganapathisubramani et al. 2007). These experimental diagnostics allowed to reconstruct the full instantaneous local velocity gradient tensor and to observe the evolution of the coherent structures in turbulent flows.

Although the currently available PIV systems have proved to be adequate in characterizing the activity of the small scales, all the aforementioned experimental works have the limitation of investigating flows at relatively low Reynolds numbers (\(Re_\lambda \leqslant 150\), where \(Re_\lambda\) is the Reynolds number based on the Taylor microscale). As a matter of fact, flows at higher Reynolds numbers are of great interest for the understanding of turbulence, in that the separation between the large and the small scales of turbulence is large, which allows, for instance, to assess the proposed Reynolds number scaling of the small-scale structures. Moreover, the theoretical description of turbulence implies a clear separation of the large and small scales, which is only reached at high Reynolds numbers. High Reynolds number flows are also encountered extensively in practical and industrial applications. Nevertheless, the low spatial resolution of the PIV systems used so far represented a limitation in the highest achievable Reynolds numbers of the flow (Westerweel et al. 2013). In turbulence, an increase in the Reynolds number of the flow results in an almost proportional decrease in the size of the Kolmogorov length scale (\(\eta\)). For an accurate description of the small-scale motions, a spatial resolution of \(3 \eta\) (three times the Kolmogorov length scale) is required, as pointed out by Buxton et al. (2011), and Worth et al. (2010), even if this condition can be somewhat relaxed in case of high overlap of the interrogation windows (see Tokgoz et al. 2012). In this context, long-range μPIV emerges as a promising technique. The use of a long-distance microscope in front of the camera allows to increase the spatial resolution, and, consequently, permits to investigate flows at higher Reynolds number, however, at the cost of losing information on the large-scale flow structures.

Following to some sporadic and pioneering applications (i.e., Urushihara et al. 1993, among the others), the use of long-range μPIV has recently experienced a certain expansion. One of the first studies with the technique was aimed at resolving the small-scale turbulence in a pipe flow. The investigation was performed by Lindken et al. (2002), who used a Questar QM-1 long-distance microscope at a magnification of \(2.6\), and at a working distance of 550 mm. They validated the μPIV set of data by comparison of the main turbulence statistics with standard PIV and with DNS. Of particular originality is the work of Zeff et al. (2003), who relied on long-range microscopy to estimate the three components of the velocity vector. Invoking the hypothesis of local linearity of the flow within the measurement volume, and using a system of three high-speed cameras, each of those focusing on a different laser sheet, allowed them to estimate the dissipation and the enstrophy of the turbulent flow, from all the nine velocity gradients, although in a single point and at moderate \(Re_\lambda\). Later on, long-range μPIV was applied to investigate the laminar separation bubble above a helicopter rotor tip, induced by an adverse pressure gradient (Raffel et al. 2006). In the same year, Kähler et al. (2006) could successfully measure the turbulence in the near-wall region of a boundary layer. The authors compared the performance of the two leading manufacturers in long-range microscopes. In the experiment, a local seeding of the air flow was adopted to achieve an adequate particle concentration within the measurement domain. A data processing with ensemble correlation methods led to a single-pixel resolution in the measurements, even if the instantaneous turbulent fluctuations were averaged out by this procedure.

Recently, Alharbi and Sick (2010) used a long-range μPIV system to study the flow over the internal combustion cylinder head, in the region between the intake and the exhaust valves. The technique proved adequate to resolve and follow the small-scale rotational structures in the combustion chamber. To simultaneously investigate the near-wall region and the large-scale properties of a turbulent boundary layer, Cierpka et al. (2013) developed a system with multiple fields of view. Using single-pixel correlation (Westerweel et al. 2004), they explored the outer layer with a large field of view using standard optics, whereas the Infinity K2 long-range microscope was focused on the near-wall region. In the inner layer, the processing with a PTV algorithm helped to minimize random and systematic errors that occur due to the spatial averaging. An analogous experiment was performed later on by de Silva et al. (2014). The authors set up a PIV system composed of eight cameras for the study of the outer region, and a synchronized high-speed camera for the inner layer. The turbulent statistics obtained were then compared with the literature for the sake of validation. The aim of the work was the investigation of the scale interactions in a turbulent boundary layer, at high Reynolds numbers. The rich variety of works that validated μPIV by comparison of the velocity statistics proves the reliability of the technique. Furthermore, the literature review reveals that a spatial resolution on the order of \(100\,\upmu {\rm m}\) can be achieved at the current technical standards.

The goal of the present work is to assess and validate the performance of long-range μPIV in the study of the small-scale motions in turbulence. We consider a jet flow at a Reynolds number based on the Taylor length scale of 350 (\(Re_\lambda \approx 350\)). The high spatial resolution of the long-range μPIV systems allows us to examine the instantaneous small-scale coherent structures at these high Reynolds numbers, which is an element of novelty. Long-range μPIV has been employed scarcely so far to investigate the behavior of the small scales. And when it was the case, the technique has been used to obtain the velocity statistics. Here, the scaling of the vortex cores and the predominant 2D flow topologies are explored.

The outline of the paper is as follows. Section 2 is devoted to the design, the description, and the validation of the long-range μPIV experiment. Hot-wire anemometry is used to validate the long-range μPIV measurements by comparison of the turbulence statistics. Then, the velocity fields obtained from the long-range μPIV experiment allow to characterize the small-scale flow structures in the turbulent flow under investigation (Sect. 3). The shape and the size of the coherent structures of vorticity and dissipation as well as their spatial organization are discussed. Furthermore, the 2D topological content of the turbulent flow is investigated, based on the statistical analysis of the invariants of the reduced velocity gradient tensor (VGT). The main findings are then summarized in Sect. 4.

2 Experimental setup

2.1 The design of the experiment

The air jet is issued from a nozzle with a diameter of \(D\) = 8 mm, at a mean velocity of \(U_{\rm J}\) = 125 m/s, as measured with a Pitot tube. The governing non-dimensional numbers at the nozzle can thus be estimated as \(Re_{\rm D} = 6.6 \times 10^4\) and \(Ma\) = 0.37. While the jet is weakly compressible near the nozzle, downstream at the measurement location the Mach number has reduced to <0.1 so that incompressibility can be assumed again. Further details on the settling chamber and the shape of the nozzle are given by Slot et al. (2009). The PIV experiment was designed on the basis of a preliminary characterization of the jet flow, which was performed using constant temperature hot-wire anemometry (CTA). The hot-wire measurements were taken with a Dantec 55P11 sensor, with an overheat adjustment of \(0.7\), in order to keep the temperature of the sensor at a constant temperature of \(220\,^\circ \hbox {C}\). The feedback control of the wire temperature was established through a Dantec Dynamics 56C17 CTA Bridge. The main aim was to estimate the turbulent length scales at different downstream distances from the nozzle. Further details on these hot-wire anemometry measurements can be found in Fiscaletti et al. (2013).

The CTA measurements also serve as a benchmark for the validation of the PIV results. The mean dissipation rate in the jets is estimated with (Panchapakesan and Lumley 1993):

where \(U_{{\rm c}}\) is the centerline velocity, and \(r_{1/2}\) is the jet half-width. Based on the local dissipation rate, the Kolmogorov scales can be computed with (Pope 2000):

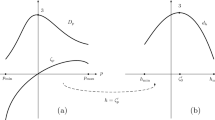

where \(\nu\) is the kinematic viscosity. Furthermore, hot-wire anemometry allowed to determine the turbulence statistics of the jet flow. In particular, the radial profiles of the mean and the rms velocities were scaled with the mean centerline velocity \(U_{\rm c}\) of the flow. At each downstream position \(x\), the velocity profiles collapsed on a single curve after scaling the radial distance \(r\) on \(r_{1/2}\), thus showing the self-similar behavior typical of the jet flows for \(x/D > 20\) (Figs. 1, 2). From this characterization, further information on the jet flow could be inferred, such as the spreading rate and the decay rate of the centerline velocity. These exhibited a good agreement with other studies available in the literature (i.e. Panchapakesan and Lumley 1993; Hussein et al. 1994). The maximum deviation for both the spreading rate and the decay rate is within 5 %, when compared with the study by Hussein et al. (1994). Based on the acquired velocity statistics and under the hypothesis of isotropic turbulence, the Taylor micro-scale was estimated using (Taylor 1935):

where \(u_{\rm rms}\) is the rms of the axial velocity component.

The μPIV measurements were taken along the centerline at a downstream distance of \(x/D = 70\) from the nozzle. At this location, the most relevant turbulent quantities were determined as \(\eta = 57\,\upmu {\rm m},\,\lambda _{\rm T} = 2.19\,{\rm mm}\), and \(Re_\lambda = u_{\rm rms} \lambda _{\rm T} / \nu = 367\). A detailed summary of the estimated flow characteristics can be found in Table 1.

2.2 Long-range μPIV

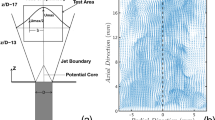

The μPIV system consisted of a Nd:YAG laser (Quanta-Ray, Spectra-Physics), a CCD-camera with 1,040 \(\times\) 1,376 pixels format sensor (pixel size, \(d_{\rm r} = 6.45 \,\upmu {\rm m})\), and a long-distance microscope. A sketch of the experimental setup is provided in Fig. 3. The main design parameters are summarized in Table 2. For the present set of measurements, we used the Questar QM-1, whose working distance ranges from 550 to 1,560 mm. If no shadowing is introduced in the measurements, the Questar QM-1 and the Infinity K2 can provide particle images of similar quality, as shown by Kähler et al. (2006). The magnification factor adopted was 2.5, with a working distance of 560 mm, and \(f^{\#} = 8.7\). The working distance is more than an order of magnitude higher than the jet half-width at the measurement location (52.2 mm), which is deemed sufficient to avoid any perturbative effect on the flow. As PIV seeding, we used DEHS droplets (Di(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate, sebacic acid), generated from a Laskin nozzle. One of the most challenging aspects in the design of long-range μPIV experiments is to achieve a sufficient concentration of particle images within the field of view. In jets, this is intimately linked to the way the flow is seeded. From the analytical formulation of the mean velocity profile in round jets (Pope 2000), the mass flow at 70 diameters downstream the jet nozzle is more than twenty times higher than at the nozzle exit. This difference is due to entrainment of ambient fluid, which would suggest to seed the entraining ambient flow. On the other hand, the seeding of the whole ambient would create an optical barrier between the measurement domain and the microscope. Therefore, this option was deemed impractical. Instead, we decided to directly insert particles within the air jet. The injection of particles was done in the air supply line more than two meters upstream of the jet nozzle, so to achieve a uniform concentration of tracer particles within the flow, and to avoid any perturbation that would result from introducing a seeding device into the flow. Two seeding generators were used, pressurized at 2.2 bar by a compressor. Thus, the air jet under investigation was supplied by both the seeded flow, and the unseeded air flow from a second compressor, as sketched in Fig. 3. A nozzle velocity of 125 m/s was again measured using a Pitot tube, which confirmed that the jet exit conditions were the same as for the hot-wire measurements. From the manual of the particle generators (manufactured by PIVTEC GmbH), the droplet size distribution of the tracers has its peak for a size of \(1\,\upmu {\rm m}\). Based on a particle diameter of \(1\,\upmu {\rm m}\), the response time of the seeding droplets is computed to be \(3\) \(\upmu {\rm s}\). On the other hand, the Kolmogorov time scale at the measurement location is \(\tau _{\eta } = \sqrt{\nu / \varepsilon } = 200\,\upmu {\rm s}\), therefore two orders of magnitude larger than the time response of the particles. This indicates that the velocity fluctuations in the flow can be followed accurately by these particles. An estimate of the average number of particles per image was obtained by counting the number of local maxima in the light intensity of a PIV image. As many of them are the result of background noise in the image, we constructed a plot which relates the number of local maxima to the light intensity that is considered as a background noise threshold. The trend between the number of maxima and the threshold is showed in Fig. 4 for a typical pair of PIV images. A reliable estimate of the particles per image pair can be retrieved as the number of local maxima obtained in the region of the graph where the slope suddenly reduces (Fig. 4). In this way, the number of particles per cross-correlation window of \(64 \times 64\) pixels was estimated to range between 9.5 and 15. Considering an average number of particles per window of 12, the volume fraction of particles at the nozzle can be estimated as \(5.2 \times 10^{-5}\), which corresponds to a mass fraction of \(4.8 \times 10^{-2}\). The range of volume load fractions for two-phase flows is from \(10^{-2}\) to \(10^{-5}\), where the interaction between the two phases is of the type “two-way coupling”, namely that the continuous phase and the dispersed phase affect each other mutually (see Poelma 2004; Elghobashi and Truesdell 1993; Elghobashi 1994). This implies that the volume load of particles in the present jet flow at the nozzle is not negligible, and the droplets interact with the flow. On the other hand, the “two-way coupling” between the two phases is confined to the region in the proximity to the nozzle, since the air entrainment rapidly reduces the volume fraction. At the measurement location, the volume fraction of particles is estimated to be \(2.6 \times 10^{-6}\), and the effect of the particles on the flow is considered to be negligible. Therefore, at the measurement location, the small-scale motions of turbulence are not affected by the volume load of particles. Furthermore, we estimate the average particle image diameter from the autocorrelation function of the image intensity. The diameter is around \(3\) pixels based on the width of the autocorrelation function at \(50\,\%\) of the peak value. Some variation in the particle image diameter exists because of the short depth of focus (Adrian and Westerweel 2011, p 9).

Number of local maxima in the light intensity in a random PIV image pair, above a given light intensity threshold. The range marked with red circles yields a number of particle images per PIV image pair ranging between \(10^{4}\) and \(6 \times 10^{3}\). This results in a number of particle image per correlation window ranging between 9.5 and 15

Typically, the short depth of focus represents a critical point in μPIV measurements. In PIV, the depth of focus is commonly larger than the thickness of the light sheet, so that all particle images appear in focus. But in μPIV, the depth of focus might be less than the thickness of the light sheet. To overcome this limitation, the thickness of the light sheet was reduced using a cylindrical lens, so to match the size of the depth of focus set by the long-range microscope. Furthermore, both the depth of focus and the light sheet were aligned carefully. The resulting thickness of the laser sheet was estimated from a recording of the light reflected on a plexiglass plate, positioned at an angle of around \(45^{\circ }\) with respect to the camera (1st reflection, in Fig. 5, right top). The recorded image (Fig. 5, left top) was averaged along the vertical direction, in order to gain the horizontal distribution of the light intensity (Fig. 5, left bottom). We define the thickness of the light sheet based on the location where the intensity dropped to 50 % of the peak intensity. This assumption appears reasonable when considering that the contribution of particle images to the correlation coefficient goes with their intensity squared. Particle images characterized by an intensity lower than 50 % of the maximum value produce a correlation that is only 25 % of the correlation value obtained for particle images of maximum intensity. Using this convention, the thickness of the light sheet was estimated to be around \(180\,\upmu {\rm m}\), corresponding to \(3.3 \eta\). Following the book by Adrian and Westerweel (2011, p 173), the Rayleigh length of the light sheet was estimated to be \(34.6\,{\mathrm{mm}}\), thus more than an order of magnitude larger than the field of view.

Right sketch of the procedure for the estimate of the thickness of the laser sheet. Left, top recorded image of the laser sheet, as reflected by the external surface of a plexiglass plate (1st reflection) positioned at an angle of \(45^{\circ }\) with respect to the camera. Note that the gray values have been inverted. Left, bottom average light intensity distribution used to estimate the thickness of the light sheet

Data were acquired at a frequency of \(5\,Hz\). A total of \(11 \times 10^{3}\) image pairs were collected, divided over 4 runs (3,500, 3,500, 2,000, 2,000). Each dataset of image pairs was processed through a cross-correlation algorithm (DaViS7.2 by LaVision). A two-pass grid refinement was adopted, with a final interrogation window of \(64 \times 64\) pixels, and a 50 % window overlap. The linear size of the interrogation window was \(160\,\upmu {\rm m}\), which corresponds to \(2.9 \eta\) at the measurement location. The field of view was \(3.43 \times 2.60\) mm, equivalent to \(62.4\eta \times 47.3\eta\), or \(1.68\lambda _{\rm T} \times 1.27\lambda _{\rm T}\), where \(\eta\) and \(\lambda _{\rm T}\) are the Kolmogorov length scale and the Taylor length scale, respectively, as derived from the μPIV data (see Table 4). A time delay of \(3\,\upmu {\rm s}\) was chosen between the first and the second laser pulse, yielding an average particle image displacement of 11.8 pixels.

The median test for the detection of the spurious vectors was applied to the present set of data (Adrian and Westerweel 2011, among others). The percentage of good vectors was higher than \(94\,\%\) throughout the whole dataset. This high percentage of good vectors allowed the application of the algorithm for the replacement of the outliers based on linear interpolation of the neighbors. Furthermore, the level of peak-locking in the μPIV data was checked. Peak-locking is a bias error that affects a PIV measurements in its subpixel accuracy (Adrian and Westerweel 2011, among others). This bias depends on a lack of information in the three-point centroid fitting that is used for a subpixel estimation of the displacement. Figure 6 shows the level of peak-locking bias error in the PIV measurements. Clearly, the measurements are affected by a mild peak-locking. When an iterative multi-step window deformation approach, as the one implemented in DaViS7.2, is used to process the image pairs, the peak-locking bias error produces a biasing toward \(1/2\)-integer subpixel displacements (Scarano 2002) as observed in Fig. 6.

The autocorrelation of the measured velocity provides also information on the level of uncorrelated noise in the PIV measurements. As explained by Poelma (2004) and Benedict and Gould (1998), the autocorrelation function of a noisy velocity signal is the sum of the autocorrelation function of the velocity fluctuations and the correlation of the noise. The contribution of the uncorrelated noise to the autocorrelation function is confined to a small region around the peak extending one window size in each direction. Therefore, an estimate of the contribution of the true velocity fluctuations to the correlation peak was obtained by fitting a parabola to autocorrelation function of the streamwise velocity \(R_{11}\), using the 2nd to the 5th point away from the peak. These points are not affected by the noise. At \(\Delta x_{1} = 0\), the gap between the fitted parabola and \(R_{11}\) peak represents the square of the estimated noise level. As it can be appreciated from Fig. 7, the measurements are affected by a noise level less than 0.16 m/s (<6 % of the \(u_{\rm rms}\)). Anyway, the noise in the PIV data was attenuated a-posteriori by applying a regression filter. The filter replaces the value measured experimentally in a certain point of the domain, with the value obtained in the same point by least-square fitting a parabola to the velocity in a \(5 \times 5\) neighborhood around the point. Details on this linear filter is given by Elsinga et al. (2010). In the next Subsection, and in the Sect. 3, we exclusively deal with filtered data.

2.3 Validation by comparison of the turbulence statistics

The PIV measurements were validated by comparison of the mean, rms, skewness, and kurtosis of the streamwise velocity component, with the results of the hot-wire anemometry measurements. The result of this comparison is given in Table 3. The measurement uncertainty was estimated with the bootstrapping method. The discrepancy in the mean between hot-wire anemometry and PIV can be most likely attributed to a slightly different radial location of the measurements. The other velocity statistics show a good agreement.

Furthermore, we derived from μPIV some of the main properties of the turbulent flow that had been previously computed based on the flow statistics measured with hot-wire anemometry. In homogeneous isotropic turbulence, the following Equation can be used (Pope 2000) to calculate the average rate of dissipation:

where \(u_{1}\) is the streamwise component of the velocity vector, \(\langle \cdot \rangle\) denotes a temporal averaging, and \(\nu\) is the kinematic viscosity. The velocity gradient in streamwise direction was computed using a central difference scheme. From Eq. 3, it was possible to derive the Taylor micro-scale (\(\lambda _{\rm T}\)), and, from that, the Reynolds number based on the Taylor length scale (\(Re_{\lambda }\)). Equation 2 was used to determine the Kolmogorov length scale based on μPIV data. The flow characteristics as determined from the μPIV data are collected in Table 4. They compare very well with those determined from the hot-wire anemometry, as presented in Table 1, which is a further validation of the present μPIV measurements.

3 Results

From the PIV data, the reduced VGT could be computed. A central difference method allowed the velocity gradients to be extracted from the discrete set of filtered experimental data. The reduced VGT is a \(2\times 2\) matrix \({\mathbf {A}}\) such that:

where the subscripts 1 and 2 represent the streamwise and spanwise directions, respectively. Based on \(\mathbf {A}\), the vortical structures are then examined, which typically populate the fully-developed region of the jet. These structures tend to appear in the shape of elongated vortices, called “worms” after the works by Siggia (1981) and Ashurst et al. (1987), among others. In particular, we focus on the vortices in the 2D domain, which are regarded as the footprints of the worm-like structures on the intersecting plane of measurement. We characterize them in terms of circulation, rate of occurrence, and size of the core. Possible connections between vortices and regions of intense dissipation are also examined in the following, since a link between them has already been ascertained in the literature at lower Reynolds number (Ganapathisubramani et al. 2008; Chacin and Cantwell 2000). The way to detect and define a vortex inside a velocity vector field is still somewhat controversial. In the literature on turbulence, many schemes and criteria for vortex identification are reported. Recently, a detailed review of vortex identification criteria in turbulence data was given by Chakraborty et al. (2005). The swirling strength criterion proposed by Zhou et al. (1999), also known as the \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\)-criterion, exhibits some advantages that made it particularly suited for the present study. The most relevant advantage is the capacity of detecting vortices independently of their convection velocity. Another advantage is that the swirling strength is sensitive only to the in-plane rotation, and is not affected by shear as is the vorticity component. The \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\)-criterion takes into consideration the imaginary part of the eigenvalues of the VGT (\(\lambda _{\rm ci}\)) in each point of the velocity field. A vortex is detected if either one point or spots of multiple points was/were characterized by \(\lambda _{\rm ci} > 3.6 \lambda _{\rm ci,rms}\), where \(\lambda _{\rm ci,rms}\) was computed considering only the nonzero \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) values. The application of this threshold allowed to detect 10,423 intense vortices, distributed over the 11,000 velocity fields. With the aim of identifying the subgrid position of the centers of the vortices, we computed the centroid of the \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) distribution belonging to the same vortex core. The spatial extent of the vortex was estimated as the largest box that could surround the center, where all the included points were characterized by a decreasing vorticity magnitude when moving from the center to the periphery of the box. The circulation was calculated as follows:

where \({\rm d}x_{1}\) and \({\rm d}x_{2}\) is the vector spacing in the streamwise and the spanwise direction, respectively, \(N\) is the number of points inside the box, and \(\omega _{3}(j)\) is the out-of-plane vorticity component in the jth point of the box, computed locally as follows:

The mean circulation obtained for vortices with \(\varGamma > 0\) was 1.932 × 10−3 m2/s, whereas the mean circulation obtained for vortices with \(\varGamma < 0\) was −1.926 × 10−3 m2/s. In Fig. 8, the pdfs of the circulation for both positive and negative values of \(\Gamma\) is given.

The autocorrelation functions of the vorticity (\(\omega _{3}\)) and \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) allowed for a statistical evaluation of the size of the vortical structures (Fig. 9). As expected, the two autocorrelation maps look very similar, in particular in the shape of the central peak. This allows to obtain a confident estimate of the size of the diameter for the structures of intense vorticity. In Figs. 10 and 11, two longitudinal sections of the autocorrelation maps of both \(\omega _{\rm 3}\) and \(\lambda _{{\rm ci}}\) are shown. Due to the axial symmetry with respect to the origin of these specific autocorrelation maps, we introduce here the radial shift \(r = \sqrt{\Delta x_{1}^2 + \Delta x_{2}^2}\), and we present the profiles of the autocorrelation coefficient versus the radial shift \(r\). The two profiles permit to estimate the diameter of the core at around \(10 \eta\), after taking a value of \(R = 0.5\) as a threshold for the edge of the vortical structure. A confirmation for this vortex diameter is obtained by evaluating the local profile of the \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\), in the instantaneous contour map of \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\). In Fig. 12, a contour map reveals at least four intense vortical structures. The cores of these vortices are intersected along the lines indicated (black), and the corresponding instantaneous profiles are given in Fig. 13. The diameter of the four vortex cores ranges between \(9 \eta\) and \(12 \eta\). This is in agreement with the measurements of Ganapathisubramani et al. (2008), and with the simulations by Jimenez et al. (1993), even though at higher \(Re_{\lambda }\). In DNS simulations at unprecedented high Reynolds numbers (\(Re_{\lambda } >\)1,000), Ishihara et al. (2013) reported a thickness for the intense vortices of \(10 \eta\), based on a visual inspection of instantaneous snapshots of vorticity isosurfaces. Hence, the present experimental results further support a scaling for the vortex diameter with the Kolmogorov length scale \(\eta\). The tendency of the fine scales to organize themselves in elongated vortices whose diameter scales with the Kolmogorov length scale was also found in turbulent boundary layers (Herpin et al. 2013). This observation suggests that the presence of these fine-scale coherent structures in fully-developed turbulence is independent of the flow under analysis, and can be considered a universal property.

Section of the autocorrelation coefficient map of vorticity (as in Fig. 9)

\(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) profiles across selected vortex cores (as indicated in Fig. 12)

The estimate of the local instantaneous dissipation rate can be obtained with:

where \(\mathbf {A}\) is the reduced VGT in a point. Similarly to what has been done for \(\omega _{3}\) and \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\), the autocorrelation map of \(\varepsilon\) was computed revealing an axial symmetry. This allowed to statistically evaluate the shape of the regions of intense dissipation. In Fig. 14, again a sharp peak can be observed in the cross-correlation map, but in this case, the tail still corresponds to significant levels of correlation up to the edge of the observation domain. These considerations over the correlation map represent a clear indication for a dual scale (sheet-like shape) in the highly dissipative regions, which is consistent with the pancake-shape observed at a lower Reynolds number with cinematographic stereo-PIV (Ganapathisubramani et al. 2008). In particular, the width of the central peak (\(10 \eta\)) would then correspond to the thickness of such sheet, while width of the tails (of the order of the observation domain) would be associated to the length of the sheet. A confirmation of this observation can be found in the instantaneous contour maps of \(\varepsilon\), a typical example of which is given in Fig. 15.

Contours of the instantaneous rate of dissipation \(\varepsilon\). The white dots indicate the centers of the vortical structures in Fig. 12

As observed by Ganapathisubramani et al. (2008), the cluster of vortex tubes increases the probability for regions of intense dissipation to occur. If this tendency is independent of the Reynolds number of the flow, the present investigation should show the same characteristic. For this reason, a correlation between the presence of vortices within the field of view, and of regions of intense dissipation was computed. A threshold of \(\lambda _{\rm ci} = 3.6 \lambda _{\rm ci,rms}\) and \(\varepsilon = 3 \varepsilon _{\rm rms}\) was imposed, the latter in order to discriminate between normal and intense turbulent dissipation, with \(\varepsilon _{\rm rms} = 338.5\,{\rm m}^2/{\rm s}^3\). From the literature, it is expected that when at least one vortex is detected within the field of view, one or more regions of intense dissipation are found, whereas when no vortices are detected, the turbulent dissipation is also lower than the imposed threshold. In 79.2 % of the cases, the presence/absence of vortices within the field of view was accompanied by at least one/no region of intense dissipation. The described thresholding led to an absence of vortices in the field of view in 58 % of the cases, and to an absence of regions of intense dissipation in 54 % of the cases. In Table 5, the statistics on the presence and absence of regions of intense dissipation and intense vortices are given. An estimate of the distance between vortices and regions of intense dissipation can be obtained by a cross-correlation of \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) and \(\varepsilon\). A radial profile of the correlation map is given in Fig. 16. The cross-correlation map presents a peak at approximately \(9 \eta\), and it decreases when moving toward the periphery of the correlation map, therefore for a higher mutual distance between \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) and \(\varepsilon\). The mutual distance is around one order of magnitude higher than the Kolmogorov length scale, which is comparable to the typical diameter of intense vortices. Figures 12 and 15 present visualizations of \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) and \(\varepsilon\) at the same instant in time. In Fig. 15, the centers of the intense vortices, as detected from the map of \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) (Fig. 12), have also been marked as white dots. From this instantaneous map, the regions of intense dissipation appear elongated, and their shape can be regarded as the footprints of structures having two characteristic dimensions. This finding is consistent with the profile of the autocorrelation coefficient map of intense dissipation (Fig. 14), and with the description of the high dissipation regions as “sheets” (Ganapathisubramani et al. 2008) or “pancakes” (Vincent and Meneguzzi 1994). By comparing these plots, it can be seen that peaks of \(\lambda _{ci}\) are found adjacent to the peaks in dissipation. This is again consistent with the suggested organization of dissipation and vortices (Ganapathisubramani et al. 2008; Chacin and Cantwell 2000). On the other hand, it seems that the vortex tubes are all oriented perpendicularly to measurement plane, as their footprints (except for the structure A) are nearly round. If the vortex tubes are not perpendicular, we expect an elliptical footprint. Therefore, even though in a situation of isotropic turbulence on average, the structures of intense dissipation could have locally a preferential orientation at a particular instant in time. Also, in terms of the spatial organization of the two entities, it seems that the vortices are mainly located near to the short side of the sheets, rather than “surrounding“ the sheets, as suggested by Ganapathisubramani et al. (2008) in the “cartoon” of their Fig. 19. This would suggest a scenario that is more consistent with the very recent observations by Ishihara et al. (2013), from DNS at very high \(Re_{\lambda }\). The authors identified layer-like structures consisting of clusters of strong vortex tubes. According to Ishihara et al. (2013), these layers are mainly found in proximity of jumps in the large-scale velocity, and are therefore characterized by intense shear, consistently with average topology of Elsinga and Marusic (2010). Nevertheless, the small field of view of the present set of data, and the lack of the third component in the velocity vector fields does not allow to check the consistency of these observations any further.

Moreover, it is of interest to consider the spatial organization and the form of the regions of maximum dissipation in the Burgers vortex, for sake of comparison with the present experimental findings. In a Burgers vortex, the dissipation is maximum at a distance of 8–12\(\eta\) from the vortex center, similarly to the present experimental results (Fig. 16). On the other hand, the maximum dissipation is organized in a circular region around the Burgers vortex core forming a ring. This a relevant difference between the theoretical model and the experiments. In fact, the present experiment and the experiment by Ganapathisubramani et al. (2008) show that the regions of intense dissipation have a sheet-like appearance (Fig. 15), which is in contrast with the vortex model by Burgers.

Furthermore, the 2D topological content of the turbulent flow was investigated, following the approach outlined by Cardesa et al. (2013) based on the invariants of the reduced VGT. The characteristic polynomial of \(\mathbf {A}\) was firstly computed:

where p and q are given by:

where p and q are the invariants of the reduced VGT. As shown by Cardesa et al. (2013), p and q represent a powerful tool in the study of the small scale topology in a 2D plane. Under the assumption of isotropy, further considerations on the statistical properties of p and q can be made, since the 2D measurement plane randomly intersects the 3D flow patterns. However, the local flow topology cannot be retrieved from the reduced VGT. The following statistical analysis of the invariants of the reduced VGT relies on \(10^{6}\) values of p and q.

If the flow can be assumed isotropic and incompressible (\(Ma < 0.1\) at the measurement location), it can be shown that (Cardesa et al. 2013):

Furthermore, homogeneity implies that \(\langle p \rangle = 0\), and \(\langle q \rangle = 0\). In Table 6, a summary of the statistics of the invariants p and q is collected. The quantity \(\langle pq \rangle / \langle p^{3} \rangle\) slightly deviates from the theoretically predicted value of \(7/6\). Analogous deviations were similarly found in other experimental and numerical studies, on different turbulent flows, such as jet, impeller-generated turbulence, and channel flow (see Cardesa et al. 2013). These were explained in terms of experimental noise and the low order of the approximation schemes for the derivatives. For the simulations, a reason for this scattering was attributed to aliasing (Cardesa et al. 2013). Despite these deviations, the analysis of the invariants gives a result that is consistent with homogeneity and isotropy of the small-scale turbulence, and with the incompressibility of the flow.

Moreover, we computed the joint pdf (jpdf) of the invariants of the reduced VGT, p and q (Fig. 17). The invariants p and q are normalized by \(\langle \omega _{3}^2 \rangle ^{1/2}\) and \(\langle \omega _{3}^2 \rangle\), respectively. The contour levels in Fig. 17 are given on a logarithmic scale. The parabola \(q = p^{2}/4\), corresponding to the boundary between real and imaginary roots of the characteristic polynomial of \(\mathbf {A}\), is also included in the graph. The jpdf exhibits the characteristic teapot-shape that was also found for other turbulent flows (Cardesa et al. 2013). This shape illustrates the higher statistical probability of some topological features to occur in turbulence. In particular, the asymmetric distribution in the jpdf implies that \(\langle pq \rangle < 0\). The quantity \(\langle pq \rangle\) can be directly related to the average enstrophy amplification \(\langle \omega _{\rm i} S_{\rm ij} \omega _{\rm j} \rangle\) within the flow, for isotropic turbulence (Cardesa et al. 2013):

The quantity \(\langle pq \rangle\) for our data is indeed negative (Table 6). This implies that the amplification of enstrophy is positive on average, and that vortex stretching is predominant. Following Townsend (1951), the vortex stretching term can be related to the longitudinal velocity-derivative skewness factor, \(S_{\rm o}\):

where \(S_{\rm o}\) is defined as:

Again, a negative value of \(S_{\rm o}\) is a further indication for a positive amplification of enstrophy (Table 6). This is consistent with the recent finding by Buxton and Ganapathisubramani (2010), who examined the experimental dataset on an air jet described by Ganapathisubramani et al. (2007).

4 Conclusions

Long-range μPIV was applied to resolve the small-scale motions in the fully-developed region of an axisymmetric air jet at high Reynolds number. The measurement was taken along the jet centerline, at a downstream distance of 70 nozzle diameters from the nozzle exit, in a plane parallel to the axis of the jet. The vector spacing of the PIV data was 1.5\(\eta\), obtained at \(Re_\lambda \approx 350\), where \(\eta\) is the Kolmogorov length scale, which was estimated to be 55 \(\upmu\)m. A Questar QM-1 long-distance microscope was used, by which we obtained a magnification factor of 2.5 at a working distance of 560 mm. The main difficulties related to this kind of diagnostic are achieving a sufficiently high seeding concentration within the field of view, and the precise overlap between the light sheet and the object focal plane within the depth-of-field of the optics, to avoid the illumination of the out-of-focus particles. The first four statistical moments of the turbulence fluctuations, namely mean, rms, skewness, and kurtosis, were computed from the PIV data and compared with data from hot-wire anemometry. The comparison revealed a good agreement for rms, skewness, and kurtosis, since these statistics are less sensitive to the radial location of the measurement domain, within the jet flow. Furthermore, we investigated the vortical structures, which populate the far-field of jets, as described in the literature. The 2D PIV system allowed to examine only the signature on the intersecting measuring plane of these elongated 3D vortical structures (in the shape of “worms”). After identifying these with the \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\)-criterion proposed by Zhou et al. (1999), they were investigated with a particular focus on their circulation, rate of occurrence, and size of the core. The present work reconfirmed that the core of the vortical structures scales with the Kolmogorov length scale \(\eta\), with a diameter of around \(10 \eta\), consistent with the findings by Jimenez et al. (1993), Ganapathisubramani et al. (2008), Ishihara et al. (2013) and Herpin et al. (2013) in a turbulent boundary layer. Moreover, the regions of intense dissipation tend to assume a sheet-like shape. It was also found that the occurrence of the vortical structures is intimately linked with the presence of regions of intense dissipation, as already reported by Ganapathisubramani et al. (2008). An estimate of the nominal distance between vortical structures and highly dissipative regions was obtained by cross-correlating \(\lambda _{\rm ci}\) and the rate of dissipation \(\varepsilon\). A clear peak in the correlation map was found for a separation distance of \(9 \eta\), thus comparable to the typical diameter of intense vortices.

Furthermore, we applied the approach suggested by Cardesa et al. (2013) in the analysis of the flow topology from the reduced VGT. The joint pdf of the two invariants of the reduced VGT allowed to determine the statistical preponderance of the different flow topologies. The jpdf exhibited the characteristic teapot-shape that was also found in other turbulent flows (Cardesa et al. 2013). The asymmetric distribution of the jpdf implies \(\langle pq \rangle < 0\) (where p and q are the invariants of the VGT), which is an evidence for the amplification of enstrophy and for the predominance of vortex stretching. Additionally, statistics of p and q were consistent with the hypothesis of homogeneity and isotropy of the small scales. A mild peak-locking bias error in the PIV data could explain the small deviations from the analytical predictions.

In conclusion, the small scales of turbulence could be confidently resolved in an air jet at high Reynolds number. This was possible by performing long-range μPIV. The experimental study of the structures of vorticity and of intense dissipation, and the analysis of the flow topology revealed a behavior of the small-scale motions consistent with previous works, at lower Reynolds number.

References

Adrian RJ, Westerweel J (2011) Particle image velocimetry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Alharbi AY, Sick V (2010) Investigation of boundary layers in internal combustion engines using a hybrid algorithm of high speed micro-PIV and PTV. Exp Fluid 49:949–959

Ashurst WT et al (1987) Alignment of vorticity and scalar gradient with strain rate in simulated Navier–Stokes turbulence. Phys Fluid 30:2343–2353

Benedict L, Gould R (1998) Concerning time and length scale estimates made from burst-mode LDA autocorrelation measurements. Exp Fluid 24:246–253

Buxton ORH, Ganapathisubramani B (2010) Amplification of enstrophy in the far field of an axisymmetric turbulent jet. J Fluid Mech 651:483–502

Buxton ORH, Laizet S, Ganapathisubramani B (2011) The effects of resolution and noise on kinematic features of fine-scale turbulence. Exp Fluids 51:1417–1437

Cardesa JI et al (2013) Invariants of the reduced velocity gradient tensor in turbulent flows. J Fluid Mech 716:597–615

Chacin JM, Cantwell BJ (2000) Dynamics of a low Reynolds number turbulent boundary layer. J Fluid Mech 404:87–115

Chakraborty P, Balachandar S, Adrian RJ (2005) On the relationships between local vortex identification schemes. J Fluid Mech 535:189–214

Chong MS, Perry AE, Cantwell BJ (1990) A general classification of threedimensional flow fields. Phys Fluid A 2:765–777

Chong MS et al (1998) A study of the turbulence structures of wall-bounded shear flows using DNS data. J Fluid Mech 357:225–248

Cierpka C, Scharnowski S, Kähler CJ (2013) Parallax correction for precise nearwall flow investigations using particle imaging. Appl Opt 52:2923–2931

de Silva CM et al (2014) High spatial range velocity measurements in a high Reynolds number turbulent boundary layer. Phys Fluid 26:025117

Elghobashi S (1994) On predicting particle-laden turbulent flows. Appl Sci Reas 52:309–329

Elghobashi S, Truesdell G (1993) On the two-way interaction between homogeneous turbulence and dispersed solid particles. I: turbulence modification. Phys Fluid 5:1790–1801

Elsinga GE, Marusic I (2010) Universal aspects of small-scale motions in turbulence. J Fluid Mech 662:514–539

Elsinga GE et al (2010) Three-dimensional vortex organization in a high-Reynoldsnumber supersonic turbulent boundary layer. J Fluid Mech 644:35–60

Elsinga GE et al (2006) Tomographic particle image velocimetry. Exp Fluid 41:514–539

Fiscaletti D et al (2013) Amplitude and frequency modulation of the small scales in a turbulent jet. In: 8th international symposium on turbulence and shear flow phenomena. Poitiers, France

Ganapathisubramani B, Lakshminarasimhan K, Clemens NT (2007) Determination of complete velocity gradient tensor by using cinematographic stereoscopic PIV in a turbulent jet. Exp Fluid 42:923–939

Ganapathisubramani B, Lakshminarasimhan K, Clemens NT (2008) Investigation of three-dimensional structure of fine scales in a turbulent jet by using cinematographic stereoscopic particle image velocimetry. J Fluid Mech 598:141–175

Herpin S et al (2013) Influence of the Reynolds number on the vortical structures in the logarithmic region of turbulent boundary layers. J Fluid Mech 716:5–50

Hussein HJ, Capp SP, George WK (1994) Velocity measurements in a high-Reynolds-number, momentum-conserving, axisymmetric, turbulent jet. J Fluid Mech 258:31–75

Ishihara T, Toshiyuki G, Kaneda Y (2009) Study of high-Reynolds number isotropic turbulence by direct numerical simulation. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 41:165–180

Ishihara T, Kaneda Y, Hunt JCR (2013) Thin shear layers in high Reynolds number turbulence—DNS results. Flow Turbul Comb 91:895–929

Jimenez J et al (1993) The structure of intense vorticity in isotropic turbulence. J Fluid Mech 225:65–90

Kähler CJ, Scholz U, Ortmanns J (2006) Wall-shear-stress and near-wall turbulence measurements up to single-pixel resolution by means of long-distance micro-PIV. Exp Fluid 41:327–341

Li Y et al (2008) A public turbulence database cluster and applications to study Lagrangian evolution of velocity increments in turbulence. J Turbul 9:1–29

Lindken R, et al. (2002) Turbulence measurements with μ-PIV in large-scale pipe flows. In: 11th international symposium on application of laser technology to fluid mechanics. Lisbon, Portugal, July 8–11

Lüthi B, Tsinober A, Kinzelbach W (2005) Lagrangian measurement of vorticity dynamics in turbulent flow. J Fluid Mech 528:87–118

Ooi A et al (1999) A study of the evolution and characteristics of the invariants of the velocity-gradient tensor in isotropic turbulence. J Fluid Mech 381:141–174

Panchapakesan NR, Lumley JL (1993) Turbulence measurements in axisymmetric jets of air and helium. Part 1. Air Jet. J Fluid Mech 246:197–223

Poelma C (2004) Experiments in particle-laden turbulence. In: PhD thesis, Delft University of Technology

Pope SB (2000) Turbulent flows. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Raffel M et al (2006) Micro-PIV and ELDV wind tunnel investigations of the laminar separation bubble above a helicopter blade tip. Meas Sci Technol 17:1652–1658

Scarano F (2002) Iterative image deformation methods in PIV. Meas Sci Technol 13:R1–R9

Siggia ED (1981) Numerical study of small-scale intermittency in three dimensional turbulence. J Fluid Mech 107:375–406

Slot HJ et al (2009) Experiments on the flow field and acoustic properties of a Mach number 0.75 turbulent air jet at a low Reynolds number. Flow Turbul Combust 83:587–611

Soria J et al (1994) A study of the fine-scale motions of incompressible time-developing mixing layers. Phys Fluid 6:871–884

Taylor GI (1935) Statistical theory of turbulence: parts I–III. Proc R Soc Lond Ser A 151:421–464

Tokgoz S et al (2012) Spatial resolution and dissipation rate estimation in Taylor-Couette flow for tomographic PIV. Exp Fluid 53:561–583

Townsend AA (1951) On the fine-scale structure of turbulence. Proc R Soc Lond Ser A 208:534–542

Urushihara T, Meinhart CD, Adrian RJ (1993) Investigation of the logarithmic layer in pipe flow using particle image velocimetry. In: So RMC, Speziale CG, Launder BE (eds) Near-wall turbulent flows. pp 433–446

Vincent A, Meneguzzi M (1994) The dynamics of vorticity tubes in homogeneous turbulence. J Fluid Mech 258:245–254

Westerweel J, Elsinga GE, Adrian RJ (2013) Particle image velocimetry for complex and turbulent flows. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 43:409–436

Westerweel J, Geelhoed PF, Lindken R (2004) Single-pixel resolution ensemble correlation for micro-PIV applications. Exp Fluid 37:375–384

Worth NA, Nickels TB, Swaminathan N (2010) A tomographic PIV resolution study based on homogeneous isotropic turbulence DNS data. Exp Fluid 49:637–656

Zeff BW et al (2003) Measuring intense rotation and dissipation in turbulent flows. Nature 421:146–149

Zhou J et al (1999) Mechanisms for generating coherent packets of hairpin vortices in channel flow. J Fluid Mech 387:353–396

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the European Union, under the project AFDAR (Advanced Flow Diagnostics for Aeronautical Research) no. 265695. The authors would like to thank Prof. Fulvio Scarano for lending one particle generator. We would also like to thank Edwin Overmars, Simon Toet and Jasper Ruijgrok for their precious work, assistance and help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fiscaletti, D., Westerweel, J. & Elsinga, G.E. Long-range μPIV to resolve the small scales in a jet at high Reynolds number. Exp Fluids 55, 1812 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-014-1812-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00348-014-1812-7