Abstract

Objectives

While magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered a helpful diagnostic tool in breast imaging, discussions are ongoing about appropriate protocols and indications. The European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI) launched a survey to evaluate the utilisation of breast MRI in clinical practice.

Methods

An online survey reviewed by the EUSOBI board and committees was distributed amongst members. The questions encompassed: training and experience; annual breast MRI and MRI-guided-intervention workload; examination protocols; indications; reporting habits and preferences. Data were summarised and subgroups compared using χ2 test.

Results

Of 647 EUSOBI members, 177 (27.4%) answered the survey. The majority were radiologists (90.5%), half of them based in academic centres (51.9%). Common indications for MRI included cancer staging, treatment monitoring, high-risk screening and problem-solving, and differed significantly between countries (p≤0.03). Structured reporting and BI-RADS were mostly used. Breast radiologists with ≤10 years of experience preferred inclusion of additional techniques, such as T2/STIR (p=0.03) and DWI (p=0.08) in the scan protocol. MRI-guided interventions were performed by a minority of participants (35.4%).

Conclusions

The utilisation of breast MRI in clinical practice is generally in line with international recommendations. There are substantial differences between countries. MRI-guided interventions and functional MRI parameters are not widely available.

Key points

• MRI is commonly used for the detection and characterisation of breast lesions.

• Clinical practice standards are generally in line with current recommendations.

• Standardised criteria and diagnostic categories (mainly BI-RADS) are widely adopted.

• Younger radiologists value additional techniques, such as T2/STIR and DWI.

• MRI-guided breast biopsy is not widely available.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is widely used for the detection and characterisation of breast lesions [1]. Due to many reasons, including the relatively high cost and its limited availability, MRI is utilised mainly for selected indications such as screening modality in high-risk women, preoperative evaluation of disease extent of specific breast cancer subtypes, assessment of response to neoadjuvant therapy [2,3,4,5,6]. However, indications vary due to clinical preferences, official recommendations [2, 7, 8], as well as local health care system reimbursement policies, which do change over time as the body of evidence evolves [9,10,11,12].

Another issue contributing to inter-institutional and international variations in the use of breast MRI are uncertainties regarding image acquisition and interpretation. While there is consensus about the fact that contrast-enhanced sequences are mandatory in breast MRI, the usage and value of additional techniques or specific reading protocols and criteria remain a matter of debate. Furthermore, the on-going debate about the impact of preoperative MRI regarding surgical outcomes stresses the importance of MRI-guided interventions for diagnosis and treatment planning.

In this context, the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI) decided to launch a survey among its members to gather representative data on how breast MRI is currently used in clinical practice. The results of this survey are reported in this paper.

Materials and methods

Survey design and distribution

Two board certified radiologists, one with more than 10 years of experience in breast imaging and breast MRI and one with a background in survey methodology, developed the survey. The questions encompassed: training and experience; annual breast MRI and MRI-guided intervention workload; indications and technical details of the MRI examination; and reporting habits and preferences. The full questionnaire is available online (https://de.surveymonkey.com/r/RRPQHNJ?sm=xQclpzxR8w3M4Q%2btaA9q2A%3d%3d). Once the survey was reviewed and approved by members of the EUSOBI executive board and committees the survey was published online, using a dedicated software platform (SurveyMonkey, Palo Alto, CA). EUSOBI members were invited to participate by an email that contained a link to the survey, which was sent out from the central EUSOBI office. The survey was available online for six weeks, and two reminders were sent out during this period, by email and on the EUSOBI Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/eusobieuropeansociety/?ref=aymt_homepage_panel).

Data analysis

After the survey was closed, spreadsheet data were exported for statistical analysis. Responses to the questions were extracted and summarised. Based on this first data evaluation, data were separated into groups, considering different types of institutions (academic, community, private), and different geographical areas (e.g. southern Europe vs. northern Europe as defined in Figure 1). The separation in different geographical areas was obtained by evaluating clustered data. Thus, the countries of participants that returned similar answers were considered together. The responses between the subgroups were compared using the χ2 test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.20 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Countries where the participants were working at the time of the survey (3/189 did not answer, 1.6%). Four different geographical areas were distinguished: southern; northern and eastern European countries; and non-European countries. Southern and northern countries were considered together as western European countries. Other: countries of various geographical areas in which only one person answered the survey. Footnotes: The number of responders is indicated in the horizontal -axis

Data were reported as frequencies and percentages. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normal distribution. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were used in the case of normal or near-normal distribution, median and interquartile range (IQR) in the case of non-normal distribution.

Results

A total of 189 survey participants were noted. Of these, 177 confirmed that they were EUSOBI members, yielding a response rate among members of 27.4% (Figure 1).

More than half the participants were based at an academic centre (51.9%) (Figure 2a). Board-certified radiologists, primarily, responded to the survey (90.5%) (Figure 2b). Further details are given in Table 1.

Indications for breast MRI

The most common indication was preoperative MRI in women with breast cancer (Table 2, Figure 3), followed by evaluation of breast implants (Table 2, Figure 4).

Indications for pre-operative breast MRI in different clinical settings (a) and geographical areas (b). Footnotes: Pre-OP: pre-operative MRI; ILC: invasive lobular carcinoma; APBI: accelerated partial breast irradiation; DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; B3: high-risk lesions/lesions with uncertain malignant potential

Evaluation of implants was mainly performed in patients with symptoms and inconclusive findings on conventional imaging (114/165, 69.1%). Screening in the absence of a clinical complaint was rarely performed (9.7%).

Monitoring of neoadjuvant therapy with breast MRI was more frequently performed in academic centres (92.1% compared to 78.3% in community hospitals and 70% in private hospitals, p=0.006). The difference between academic and non-academic centres was particularly evident when the evaluation of early response was considered, which was significantly more common in academic centres (84.3%, 67.4%, and 48.4% respectively, p=0.001).

Breast MRI, in patients with nipple discharge was performed mainly in cases with inconclusive findings on conventional imaging (101 of 166 answers, 60.8%), while only 6.6% always performed MRI in women with nipple discharge.

Geographical areas and their influence on indications for MRI

Indications varied between geographical regions. In southern countries (as defined in Figure 1), preoperative breast MRI was more often performed in all cancer patients rather than only for invasive lobular carcinoma (32.1%, compared to 6% in northern countries, p<0.001), and in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (50.9%, compared to 22.2% in northern countries, p=0.003), or lesions with uncertain malignant potential (32.1% compared to 11.1%, p=0.007) (Figure 3).

In northern countries, several other indications were less frequently encountered: carcinoma of unknown primary (80.9% of the cases compared to ≥ 88.5% in the other areas, p=0.030); positive margins after breast-conserving surgery (25.8% compared to ≥ 50% in the other areas, p=0.010); personalised screening (25.0% compared to ≥ 46.1%, p=0.007); inflammatory conditions (22.2% compared to ≥ 46.1%, p=0.008); and nipple discharge (45.3% compared to ≥ 80.8%, p<0.001) (Figure 4).

Screening in high-risk women and evaluation of response during neoadjuvant therapy were less frequently used in eastern countries (Figure 1) compared to western (northern and southern countries in Figure 1) and non-EU countries (65.4% compared to ≥ 83.3%, p=0.036, and 61.5% compared to 87.3%, p=0.010, respectively).

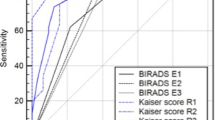

Reporting habits, diagnostic features, and MRI protocol preferences

Morphology was considered to provide the most relevant diagnostic information (Table 3). Opinions differed significantly when considering readers’ experience. Readers with more than 10 years of experience in breast imaging found the information of enhancement curves more important than did less-experienced readers (p=0.042). However, readers with less than 10 years of experience in breast imaging and breast MRI tended to prefer multiparametric assessment and gave higher usefulness scores for STIR/T2-weighted imaging (p=0.030), DWI (p=0.080), and MRS (p=0.117) as compared with radiologists with more years of experience. The value of morphology was considered high according to both groups (p>0.566).

Most participants utilised the general Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) viewer and/or a dedicated MRI workstation as well as a standardised setup for reporting (Table 4). No differences were found between the different settings (p>0.238), nor when considering the experience in breast imaging and breast MRI (≤ 10 years versus > 10 years, p>0.122).

The American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) [13] was used for description and rating of the examination in the majority of the cases, alone or in combination with further criteria or rating systems (Table 4). Structured reporting was widely used, usually combined with free-text (Table 4).

Reporting preferences did not show significant differences related to the clinical setting (p>0.137) or to experience (p>0.168).

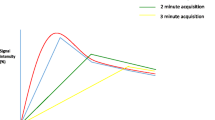

Answers regarding the technical protocols for breast MRI are provided In Table 5. A dedicated breast coil with at least four channels, and an automated injector for contrast medium application were used by almost all responders. While the majority of responders preferred three-dimensional (3D) gradient-echo sequences for dynamic, contrast-enhanced MRI, two-dimensional (2D) gradient-echo sequences were used by almost one-fourth of the survey participants. Fat saturation was favoured over non-fat-saturated sequences for both T1- and T2-weighting (77% used fat-saturated T1-weighted sequences alone and 71.4% used fat-saturated T2-weighted sequences alone, or along with non-fat-saturated sequences). A large fraction (60%) of the survey participants did acquire DWI regularly. Only a small number of participants (2%) made regular use of MRS.

Breast interventions

Only a minority of the participants (35.4%) used MR-guided interventions, either wire-localisations or needle biopsies. Of these 67 radiologists, 29 performed both biopsies and wire localisations (43.3%), three used wire localisation exclusively (4.5%), and 35 used biopsies exclusively (52.2%). The use of planning software was more common than manual planning (27 vs 17, 40.3% vs 25.4%), and sometimes both were used together (14.9%).

MRI interventions, both wire localisation and biopsy, were more often performed in an academic environment (p<0.004).

Discussion

The utilisation of breast MRI in clinical practice is generally in line with international recommendations. There are substantial differences between countries, regarding setting and reader experience. MRI-guided interventions and functional MRI parameters are not widely available.

Indications for breast MRI

The survey responders actual use of breast MRI in different clinical situations agrees with the current guidelines and statements from various societies [2, 3, 7]. However, substantial differences between different settings and countries were observed: in southern countries, preoperative breast MRI is less limited to specific breast cancer patient groups. This seems to reflect the indications of current American practice parameters [3], which suggest the use of MRI to define lesion extent and muscle involvement, regardless of the histology, or to screen for undetected contralateral cancers, although this subject is still under debate [6]. Differences in clinical practice are also likely related to the acceptance of preoperative MRI by other specialists on the multidisciplinary team, particularly surgeons.

The assessment of response during or after neoadjuvant therapy was more commonly performed in academic centres: one may assume that a greater number of women are treated with neoadjuvant therapy in institutions involved in clinical trials.

The evaluation of the response to treatment and screening of high-risk women are less frequent indications in eastern countries. This latter might reflect the current lack of organised high-risk screening programs but both may also be connected to cost-issues in situations where potential clinical effects are not immediately perceived [14, 15].

While problem-solving as an indication for breast MRI is still controversial according to the literature [2, 3], our results show that breast MRI is commonly performed in patients with inconclusive findings. This was true regardless of the setting and/or the geographical area. The term ‘problem-solving’ is used for largely different clinical situations, thus creating a wide heterogeneity in the available data and evidence. This might, at least partially, explain the divergence between guidelines and clinical practice [10, 16].

Further differences between southern and northern countries regarded indications such as evaluation of lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3), nipple discharge, inflammation, personalised screening, and evaluation after breast-conserving surgery. Northern countries seem to guide their practice more strictly in line with the available evidence that is still limited regarding specific indications [17,18,19,20,21,22].

Breast MRI was only performed by a minority of survey participants to check for implant rupture in asymptomatic women. In the United States, MRI has been suggested as a screening modality for implant rupture in asymptomatic women [23], but there is currently no evidence of its positive impact on patient treatment and outcomes.

Reporting habits, diagnostic criteria and examination protocols

The interpretation of breast MRI is a challenging task due to the abundance of diagnostic criteria. Most participants of this survey considered morphology the most important feature when evaluating a lesion, along with the signal intensity time curve type and the lesion appearance on T2-weighted sequences. We found that younger generations of breast radiologists gave more importance to multiparametric breast MRI, including T2-weighted as well as DWI. This indicates a personal choice of young generations, who prefer to report breast MRI looking at all available multiparametric data and do not focus solely on dynamic post-contrast images. Several studies already proved the usefulness of these approach [24, 25]. In the last years, many centres – in particular academic centres - introduced in their protocols both fat-suppressed and non fat-suppressed T2 as well as DWI. Thus, younger generations are more used to working with this kind of images. Whether our results are related to a paradigm shift towards multiparametric imaging or simply reflect personal preferences with the more familiar technique was not investigated. In line with published recommendations, most survey responders preferred a standardised setting for image evaluation and reporting. For the latter, the use of BI-RADS [13] was as widespread as expected. This must be considered a big advantage in the community of breast specialists: the use of well-defined descriptors and diagnostic categories provides a common language, especially important for a diagnostic tool like breast MRI that is technically complex, with interpretation based on a variety of diagnostic criteria.

Additional techniques

Additional MRI techniques such as DWI and MRS have been investigated for more than a decade. While there is common acceptance that MRS is still impractical in the clinical setting [26, 27], several studies demonstrate that evaluation with DWI can improve breast MRI accuracy, particularly specificity [24, 25, 28]. Despite that, only slightly more than half of the survey participants regularly applied DWI, and the technique was considered not very important for image interpretation by one-quarter of the survey participants. This may change in the future, as reflected by the body of evidence given above, and the fact that radiologists with less than 10 years of experience in breast MRI considered DWI (and, to some degree, MRS as well) more helpful for lesion diagnosis, compared to their more experienced colleagues.

Of note, MRI protocols may in the future be tailored to specific clinical indications: while a comprehensive diagnostic scan e.g. in the preoperative setting may profit from a sophisticated multiparametric protocol [29, 30], a screening examination may rather be as short as possible to enable high patient throughput [31,32,33].

Regarding examination protocols, the vast majority of the centres follow current state-of-the-art recommendations [2, 3, 34]. Despite the traditional belief that non-fat-saturated images are more commonly used in European countries compared to the USA, we found that fat-saturated, T1-weighted sequences are most commonly used to acquire dynamic contrast-enhanced images. Fat suppression can simplify the evaluation if significant movement artefacts are present [34].

Breast interventions

The necessity to perform MRI-guided interventions for lesions visible only on MR images is stressed by a cancer rate around 20% in these lesions [35,36,37,38,39,40]. Although centres with a sufficient caseload are recommended to provide MRI-guided biopsies, our survey shows a different reality. Most survey participants did not offer MRI-guided breast interventions.

Considering these results, the importance of targeted (or “second-look”) ultrasound must be emphasised. Targeted ultrasound is a widely available approach to avoid further MRI interventions and follow-ups in a substantial percentage of patients [38]. However, for lesions not identifiable by ultrasound, MR-guided interventions are a necessity. Without these, MRI findings cannot be translated into clinical strategies [41].

Limitations

This survey specifically targeted EUSOBI members and is, therefore, potentially biased towards radiologists with a special interest in breast imaging. As is typical for surveys, the response rate was below 50% [14, 15]. Participants were not evenly distributed among European countries, a fact that is also attributable to the distribution of members within the society, with the best-represented countries being Italy, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom, while other countries such as Germany and France are less represented within the EUSOBI. Furthermore, national differences in the amount of screening and assessment examinations performed in outpatient settings and private hospitals as compared to academic centres may further contribute to these heterogeneities and thus explain the imbalance of responders per country. The grouping into different regions is due to clustered survey data. While the association of some countries with specific regions does not reflect the UN definition of European regions (http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm#europe), they reflect a similarity of clinical practice in breast MR application. Our survey required already more than 10-15 minutes. To achieve an acceptable compliance, it was not possible to add further questions regarding several other issues (breast MRI acceptance between clinicians, reasons for differences between countries and institutions, use of alternative methods for MR-guided interventions). A further survey could be of interest to analyse the points that were only raised within the current study.

Conclusions

Our survey is the first to reveal data about the actual use of MRI of the breast by the members of the EUSOBI. While substantial differences regarding several subtopics between countries of residence were noted, the following can be concluded:

-

1.

Despite on-going controversial discussions, MRI is used for breast cancer staging and problem-solving by most responders, regardless of the setting.

-

2.

Standardised diagnostic criteria and documentation (mainly BI-RADS) are generally adopted.

-

3.

Breast radiologists with ≤10 years of experience preferred additional techniques, such as DWI, hinting at a generation- rather than an evidence-based influence on the use of these techniques.

-

4.

There is no “European” breast MRI technique, as protocols vary among users. The majority of responders apply fat-saturated protocols both in T1w and T2w imaging.

-

5.

MRI-guided breast interventions are not widely available, which must be considered as a serious weakness for a more intense distribution of this technique.

The data presented allow for a better perception of the current use of breast MRI within the EUSOBI and in Europe, and highlight the need to improve the availability of MRI-guided interventions in European countries

References

Mann RM, Balleyguier C, Baltzer PA et al (2015) Breast MRI: EUSOBI recommendations for women’s information. Eur Radiol 25:3669–3678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3807-z

Sardanelli F, Boetes C, Borisch B et al (1990) (2010) Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast: recommendations from the EUSOMA working group. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 46:1296–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.015

(2013) ACR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Breast.

Hylton NM, Blume JD, Bernreuter WK et al (2012) Locally advanced breast cancer: MR imaging for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy--results from ACRIN 6657/I-SPY TRIAL. Radiology 263:663–672. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.12110748

Riedl CC, Luft N, Bernhart C et al (2015) Triple-modality screening trial for familial breast cancer underlines the importance of magnetic resonance imaging and questions the role of mammography and ultrasound regardless of patient mutation status, age, and breast density. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 33:1128–1135. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.8626

Debald M, Abramian A, Nemes L et al (2015) Who may benefit from preoperative breast MRI? A single-center analysis of 1102 consecutive patients with primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 153:531–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3556-3

Mann RM, Kuhl CK, Kinkel K, Boetes C (2008) Breast MRI: guidelines from the European Society of Breast Imaging. Eur Radiol 18:1307–1318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-008-0863-7

Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W et al (2007) American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin 57:75–89

Houssami N, Ciatto S, Macaskill P et al (2008) Accuracy and Surgical Impact of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Breast Cancer Staging: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in Detection of Multifocal and Multicentric Cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:3248–3258. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2108

Bennani-Baiti B, Bennani-Baiti N, Baltzer PA (2016) Diagnostic Performance of Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Non-Calcified Equivocal Breast Findings: Results from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS One 11:e0160346. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160346

Sardanelli F (2010) Overview of the role of pre-operative breast MRI in the absence of evidence on patient outcomes. Breast Edinb Scotl 19:3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2009.11.003

Houssami N, Turner R, Morrow M (2013) Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in breast cancer: meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. Ann Surg 257:249–255. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827a8d17

D’Orsi Carl J, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA (2013) ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System, 5th edn. American College of Radiology, Reston

Saini KS, Taylor C, Ramirez A-J et al (2012) Role of the multidisciplinary team in breast cancer management: results from a large international survey involving 39 countries. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol ESMO 23:853–859. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr352

McCutcheon S, Cardoso F (2015) Challenges in optimizing care in advanced breast cancer patients: Results of an international survey linked to the ABC1 consensus conference. Breast Edinb Scotl 24:623–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2015.06.008

Giess CS, Chikarmane SA, Sippo DA, Birdwell RL (2016) Breast MR Imaging for Equivocal Mammographic Findings: Help or Hindrance? RadioGraphics 36:943–956. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2016150205

Lorenzon M, Zuiani C, Linda A et al (2011) Magnetic resonance imaging in patients with nipple discharge: should we recommend it? Eur Radiol 21:899–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-010-2009-y

Belli P, Costantini M, Romani M et al (2002) Magnetic resonance imaging in breast cancer recurrence. Breast Cancer Res Treat 73:223–235

Morakkabati N, Leutner CC, Schmiedel A et al (2003) Breast MR imaging during or soon after radiation therapy. Radiology 229:893–901. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2293020167

Renz DM, Baltzer PAT, Böttcher J et al (2008) Magnetic resonance imaging of inflammatory breast carcinoma and acute mastitis. A comparative study. Eur Radiol 18:2370–2380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-008-1029-3

Londero V, Zuiani C, Linda A et al (2012) High-Risk Breast Lesions at Imaging-Guided Needle Biopsy: Usefulness of MRI for Treatment Decision. Am J Roentgenol 199:W240–W250. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.11.7869

Berger N, Luparia A, Di Leo G, et al (2017) Diagnostic Performance of MRI Versus Galactography in Women With Pathologic Nipple Discharge: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.16.16682

Center for Devices and Radiological Health, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2011) FDA Update on the Safety of Silicone Gel-Filled Breast Implants. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/BreastImplants/UCM260090.pdf. Accessed 23 Aug 2016

Pinker K, Bickel H, Helbich TH et al (2013) Combined contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance and diffusion-weighted imaging reading adapted to the “Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System” for multiparametric 3-T imaging of breast lesions. Eur Radiol 23:1791–1802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-013-2771-8

Baltzer A, Dietzel M, Kaiser CG, Baltzer PA (2015) Combined reading of Contrast Enhanced and Diffusion Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging by using a simple sum score. Eur Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3886-x

Begley JKP, Redpath TW, Bolan PJ, Gilbert FJ (2012) In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res BCR 14:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr3132

Baltzer PAT, Dietzel M (2013) Breast lesions: diagnosis by using proton MR spectroscopy at 1.5 and 3.0 T--systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology 267:735–746. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13121856

Woodhams R, Matsunaga K, Iwabuchi K et al (2005) Diffusion-weighted imaging of malignant breast tumors: the usefulness of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value and ADC map for the detection of malignant breast tumors and evaluation of cancer extension. J Comput Assist Tomogr 29:644–649

Pinker K, Bogner W, Baltzer P et al (2014) Improved Diagnostic Accuracy With Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Breast Using Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Diffusion-Weighted Imaging, and 3-dimensional Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging. Invest Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0000000000000029

Pinker K, Bogner W, Baltzer P et al (2014) Improved differentiation of benign and malignant breast tumors with multiparametric 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography magnetic resonance imaging: a feasibility study. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 20:3540–3549. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2810

Mann RM, Mus RD, van Zelst J et al (2014) A novel approach to contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging for screening: high-resolution ultrafast dynamic imaging. Invest Radiol 49:579–585. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLI.0000000000000057

Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Strobel K et al (2014) Abbreviated breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): first postcontrast subtracted images and maximum-intensity projection-a novel approach to breast cancer screening with MRI. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 32:2304–2310. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.52.5386

Spick C, Szolar DHM, Preidler KW et al (2015) Breast MRI used as a problem-solving tool reliably excludes malignancy. Eur J Radiol 84:61–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.10.005

Kuhl C (2007) The current status of breast MR imaging. Part I. Choice of technique, image interpretation, diagnostic accuracy, and transfer to clinical practice. Radiology 244:356–378. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2442051620

Wallis M, Tardivon A, Tarvidon A et al (2007) Guidelines from the European Society of Breast Imaging for diagnostic interventional breast procedures. Eur Radiol 17:581–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-006-0408-x

Perlet C, Heywang-Kobrunner SH, Heinig A et al (2006) Magnetic resonance-guided, vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: results from a European multicenter study of 538 lesions. Cancer 106:982–990. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21720

Abe H, Schmidt RA, Shah RN et al (2010) MR-directed (“Second-Look”) ultrasound examination for breast lesions detected initially on MRI: MR and sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 194:370–377. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.09.2707

Spick C, Baltzer PAT (2014) Diagnostic Utility of Second-Look US for Breast Lesions Identified at MR Imaging: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiology 140474. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14140474

Spick C, Schernthaner M, Pinker K et al (2016) MR-guided vacuum-assisted breast biopsy of MRI-only lesions: a single center experience. Eur Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4267-9

Ferré R, Ianculescu V, Ciolovan L et al (2016) Diagnostic Performance of MR-guided Vacuum-Assisted Breast Biopsy: 8 Years of Experience. Breast J 22:83–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.12519

Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H et al (2017) Impact of Preoperative Breast MR Imaging and MR-guided Surgery on Diagnosis and Surgical Outcome of Women with Invasive Breast Cancer with and without DCIS Component. Radiology 284:645–655. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017161449

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna. The authors would like to thank all the EUSOBI members who took the time to answer the survey.

Funding

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Pascal A.T. Baltzer.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

One of the authors has significant statistical expertise (Pascal A.T. Baltzer).

Methodology

• retrospective

• observational

• multicentre study

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Clauser, P., Mann, R., Athanasiou, A. et al. A survey by the European Society of Breast Imaging on the utilisation of breast MRI in clinical practice. Eur Radiol 28, 1909–1918 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-017-5121-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-017-5121-4