Abstract

Anti-Melanoma Differentiation-Associated gene 5 (MDA-5) Dermatomyositis (MDA5, DM) is a recently identified subtype of myositis characteristically associated with Rapidly Progressive Interstitial Lung Disease (RP-ILD) and unique cutaneous features. We reviewed PubMed, SCOPUS and Web of Science databases and selected 87 relevant articles after screening 1485 search results, aiming to gain a better understanding of the pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment approaches of anti-MDA-5 DM described in the literature. The etiopathogenesis is speculatively linked to an unidentified viral trigger on the background of genetic predisposition culminating in an acquired type I interferonopathy. The clinical phenotype is highly varied in different ethnicities, with new clinical features having been recently described, expanding the spectrum of cases that should raise the suspicion of anti-MDA-5 DM. Unfortunately, the diagnosis is frequently missed despite excessive mortality, calling for wider awareness of suspect symptoms. RP ILD is the major determinant of survival, treatment being largely based on observational studies with recent insights into aggressive combined immunosuppression at the outset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Our understanding of Dermatomyositis (DM) as a disease entity with classic skin rashes and skeletal muscle involvement [1, 2] has transformed into a heterogeneous disease with a wide array of systemic manifestations. There are many faces of DM within both juvenile and adult subtypes, ranging from classic DM, clinically hypo- and amyopathic DM (CADM), and cancer associated DM, to the more recently described forms such as anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) DM with rapidly progressive (RP) Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD).

The clinical spectrum of the Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Myopathies (IMIM) is broad and is largely defined by the presence of characteristic myositis-specific and associated antibodies (MSA, MAA)[3]. Anti-MDA5 DM is of variable frequency ranging from 7 to 10% in European cohorts to 25% in the Japanese amongst adult DM [4, 5]. Similarly, in children, the prevalence is around 10–40% of juvenile DM cases [6, 7]. Anti-MDA5 DM is typically associated with unique and varied cutaneous features (e.g. cutaneous and oral ulcerations, painful palmar papules and macules) and RP ILD, often on a background of modest muscle involvement with an aggressive course and high early mortality. Initial reports of anti-MDA5 DM arose from Japan with the description of CADM with a novel autoantibody that immunoprecipitated a polypeptide of ∼ 140 kd labelled as the CADM-140 autoantigen [8]. The target antigen was later recognized as the Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) helicase encoded by the melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, a protein involved in the innate immune response. These patients typically had RP ILD with a poor response to treatment. After initial suggestions of a milder disease in Caucasians, a biphenotypic spectrum was identified in cases reported from the United States.

Notably, the acute presentation of the disease with predominant lung involvement may result in a delay in diagnosis due to overlap of the clinical picture with other causes of acute pneumonitis such as infections, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, drug and toxin induced, among other causes. Emerging insights suggest a benefit in survival with early and aggressive treatment with a combination of immunosuppressants [9,10,11]. Most recently, a comparison with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led to some fascinating insights into this enigmatic disease. Due to the rapidly changing paradigm due to new discoveries relevant to this rare condition, we reviewed the literature to discuss the salient features and summarize the current understanding of anti-MDA5 DM by collating evidence from around the globe.

Methodology

An electronic search strategy across three databases was performed as per Gasparyan et al. [12]. Articles available on MEDLINE, SCOPUS and Web of Science, published anytime till 26th November, 2020, were reviewed using the following search words: (“dermatomyositis” OR “DM”) AND (“MDA5” OR “anti-CADM-140” OR “Melanoma Differentiation Antigen” OR “RP ILD”), “Rapidly progressive Interstitial lung disease AND dermatomyositis”, “MDA5 AND malignancy”, “MDA5 AND treatment”. Of the 408, 467 and 589 articles obtained, respectively, in each database, articles in language other than English were excluded (Fig. 1). No restrictions were applied based on the age or method of detection of the anti-MDA5 antibody [13]. After an initial screening of titles and abstracts, relevant articles were retained. The qualifying full‐text publications and their citations were carefully reviewed to determine whether information on the topic of interest was included.

All these articles were subsequently filtered by two co-authors (PM and LG) to select only those that met the objectives of this review, resulting in 87 articles. Additional information pertaining to specific sections was obtained through an individualized search strategy: initial history and reporting of cases of CADM with high mortality, analogy between anti-MDA5 DM and COVID-19, and pathogenesis and genetics of DM.

History and pathogenesis

The initial reports of a subset of amyopathic DM with RP ILD from Japan in the early 1990s reported poor outcomes despite aggressive immunosuppression (Fig. 2) [14, 15]. In a seminal paper, Sato et al. reported a new antibody against a 140 kD polypeptide by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting (against CADM 140 antigen) in 50–70% of CADM [13]. This opened the Pandora’s box for subsequent work on this new entity. The CADM 140 antigen was subsequently demonstrated to be identical to MDA5 described previously [16, 17]. MDA-5 is a Retinoic Acid Inducible Gene-1 (RIG-1)-like receptor coded by IFIH1 (interferon-induced helicase C domain-containing protein 1) gene that recognizes double stranded (ds) RNA of viruses and induces a type I interferon response through various intermediaries. The exact pathogenesis is not known and a role of infections and environmental factors superimposed on a genetic susceptibility has been proposed [18] (Fig. 3).

Proposed pathogenesis of anti-MDA5 DM. In individuals with a particular genetic factors (HLA or non-HLA), an unknown viral trigger can lead to sensing of the viral double stranded Ribonucleic Acid (dsRNA) by cytoplasmic Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRR) like Melanoma Differentiation-Associated gene 5 (MDA5)/Retinoic Acid Inducible Gene-1 (RIG-1). This in turn results in activation of mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) which in conjugation with TNF Receptor associated factors (TRAF) recruits Tank binding kinase-1 (TBK-1) and IBK kinase (IKK). These then result in phosphorylation and activation of transcription factors-Interferon Regulatory factors (IRF) 3 and 7. These translocate into the nucleus and trigger type-1 interferon production. Virus induced cell injury and lysis, may result in release of viral-MDA5 complexes/MDA5. These complexes can be recognized by antigen presenting cells (APCs) and with a subsequent activation of helper T cells and B cells, production of autoantibody against MDA5. Activated cells and autoantibodies enter the systemic circulation and encounter autoantigens resulting in a systemic autoimmune response

Infections

Viral infections are believed to induce autoimmunity and may be the eliciting event in the pathogenesis of myositis. RNA viruses such as the coxsackie and parvovirus B19 have been implicated in causation of DM in the past [19, 20]. MDA5 is a cytosolic viral RNA sensor that normally triggers an innate response and subsequent production of cytokines [interferon (IFN), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF), interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-18], activation of macrophages and helper T cells. Although, direct evidence of a specific viral trigger is lacking, it is hypothesized that RNA viruses may upregulate MDA5 expression in tissues, and the subsequent viral replication and cell lysis would release MDA5 or a viral-MDA5 complex with resultant autoantibody production against it (Figs. 2, 3). The autoimmune response may further perpetuate cell injury, exposure of self-antigens and subsequently maladaptive immune response resulting in disease [16, 21, 22]. Thus, anti-MDA5 antibodies can be a byproduct of the above process or may have a pathogenic role. The latter is supported by recent studies in which anti-MDA5 antibody concentrations correlate with the presence of RP ILD as well as relapses [23]. Furthermore, markers of macrophage activation like ferritin, IL-18 and sCD206 (marker of M2 polarization) correlate with severity of disease and poor prognosis entailing that macrophages and thus innate immunity plays an important role in the pathogenesis of disease.

A striking similarity in increasingly being recognized between severe COVID-19 and anti-MDA5 DM with a similar involvement of the lung, skin rashes, fever, fatigue and myalgia. Notably, similar blood cytokine profiles with elevated ferritin and C-reactive protein (CRP) supports the idea that severe COVID-19 may resemble a human model of anti-MDA DM [24,25,26]. The hyperinflammatory response triggered by COVID-19 in susceptible individuals culminates in widespread endothelial dysfunction, vasculopathy and thrombotic manifestations with a pathophysiologic overlap with anti-MDA5 DM [27]. The radiological picture of COVID-19 pneumonia is comparable to ILD in anti-MDA5 DM, with frequent presence of diffuse ground glass opacities (GGO) suggestive of peribronchovascular consolidations. Both these diseases might be treated with high-dose steroids, immunosuppressants and anti-cytokine therapy. A recent report identified antibodies against immunogenic epitopes with high sequence identity to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in patients of DM, suggesting a role of latent viral infection and molecular mimicry in the pathogenesis of DM [28]. Recent reports of a high flare and admission rate among patients with myositis during the pandemic create the case to explore this speculative hypothesis [29,30,31].

Genetics

Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)-DRB1*0101/*0405 and DRB1*0401/*12:02 are associated with susceptibility to anti-MDA-5 DM in the Japanese and Han Chinese [32, 33]. Both these alleles contain a shared amino acid sequence QRRAAA at positions 70–74 of the beta1 subunit of the HLA DR molecule, suggesting that these may be important in antigenic peptide presentation and the production of anti-MDA5 antibodies. However, when a focused HLA analysis was conducted across 2582 Caucasian cases of IMIM across Europe through the Myositis Genetics Consortium (MYOGEN), no significant association was found between classic HLA alleles and anti-MDA5 DM [34].

A recent multicentric GWAS study conducted involving 592 patients of IMIM identified an association between a variant of WDFY4 and CADM. The splicing mutation resulted in increased expression of truncated variant of WDFY4 that showed increased interaction with pattern recognition receptors including MDA5 and resultant NF-kB overactivation and apoptosis. Since 70% of CADM in this study were anti-MDA5 positive with co-immunoprecipitation of sera from these individuals with truncated WDYF4 protein, this variant may play a role in the susceptibility to anti-MDA5 DM. This association was not significant when examined in the 21 European patients of CADM, although this could have possibly been due to lack of statistical power owing to smaller sample size [35].

Environmental

A detailed epidemiologic study from Japan revealed that cases of anti-MDA5 DM were clustered in the rural areas around the Kiso river with a link to detection of Coxsackie virus in the water with a seasonality from October to March [36, 37]. Similar case clustering has been reported around the Yangtze river in the Jiangsu province in China. These observations may explain a higher prevalence of this subtype of DM in South East Asia. A suggested role of environmental antigenic triggers to autoimmunity in the genetically predisposed is further consolidated by these studies, paving the way for larger epidemiological exploration. Following the eliciting trigger, a cascade of events leads on to a cytokine storm with predominant type 1 interferon signature as supported by the Interferon stimulated gene (ISG15) metric and MxA protein in muscle biopsies of patients [38].

The cytokine profile in patients with anti-MDA5 DM further supports an upregulated interferon axis (IFN-γ, IFN-α, and IFN-induced protein, IP-10) alongside other proinflammatory cytokines [39, 40]. A hierarchical cluster analysis of the cytokine profiles in DM revealed two distinct clusters, with predominance of IFN-related cytokines in cluster one, 75% of which was constituted by anti-MDA5 DM and strong correlation with cutaneous vasculitis [39]. It seems plausible that cytokine mediated microvascular injury may contribute to the unique cutaneous lesions in DM and, possibly, lung involvement.

Mutations in IFIH1 that code for MDA5 are also associated with Aicardi Goutier syndrome and other mendelian autoinflammatory interferonopathies such as STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI) and Chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperatures (CANDLE). Interestingly, the latter also exhibit the interferon gene signature, and benefit from Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, suggesting another important overlap with anti-MDA5 DM [41]. Thus, it seems plausible that anti-MDA5 DM may represent an acquired form of the same type of condition [42, 43]. However, in a recent French study, no obvious pathogenic mutations were observed in genes associated with recognized monogenic interferonopathies in 21 anti-MDA5 JDM patients [40].

Clinical features

Clinical phenotype in adults with anti-MDA5 DM

The original descriptions of anti-MDA5 DM from Asia were clinically amyopathic with cutaneous vasculopathy and RP ILD [44, 45]. Soon after that, data from different ethnic backgrounds emerged, and a clinically heterogeneous entity appears to be more likely to occur in the presence of anti-MDA5 antibodies (Tables 1, 2). Initial studies from Europe and North America described it as a mild Rheumatoid Arthritis/Anti-Synthetase Syndrome (ASSD) like disease with a prevalence of 7% amongst adult DM [46,47,48]. Subsequent studies from Spain and Pittsburgh cohorts depicted a prevalence of 15–20% among all DM, similar to Asian cohorts, with over 40–60% exhibiting RP ILD and poor survival [49]50 (Fig. 4). An unsupervised cluster analysis of 83 anti-MDA5 IMIM in a recently conducted multicentric French study yielded a revelation of a new phenotype—myopathy and cutaneous vasculopathy (27%, males, Raynaud’s phenomenon, skin ulcers, digital necrosis and calcinosis, early mortality of 4.5%, intermediate prognosis) apart from the aforementioned RP ILD (18%, RP ILD in over 90%, Mechanic’s hands, early mortality of 80%, poorest prognosis), and a dermo-rheumatologic syndrome (55%, typical skin rash, arthritis and ILD, early mortality of 0%, best prognosis) [51]. This suggests that a varied presentation and prognosis of anti-MDA5-positive IMIM may be encountered, subject to ethnicity and the clinical setting, calling for proportionate attention and monitoring on follow-up.

Cutaneous

In addition to classic rashes of DM that occur in 60–70%, patients with anti-MDA5 DM may manifest cutaneous features suggestive of an underlying vasculopathy, such as cutaneous ulcers and palmar papules. The cutaneous ulcers associated with anti-MDA5 positive IMIM occur in 40–80% individuals, are deep and punched out, and commonly overly the digital pulp, knuckles, lateral nail folds, elbows and the knees, though they can also occur on the chest, back or arms [51,52,53,54].

Palmar papules are another unique feature of this subset of IMIM, reported over the palms, the palmar aspect of fingers, especially over the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints in up to 60% of patients. They are painful, with lesional biopsies suggestive of occlusive small and medium vessel vasculopathy with a type-I Interferon signature [52, 54, 55]. Tender gums and oral erosions are also characteristically described in this subset [52]. The other reported features include, eyelid edema, non-scarring alopecia (70–80%), mechanic’s hands (60%), oral ulcers (50%), psoriasiform rashes and panniculitis (20%) [52, 56] (Fig. 5).

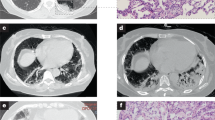

Periorbital edema in a patient with anti-MDA5 DM (top left). Chest radiograph (bottom left) showing patchy heterogeneous opacities involving both lung fields. Computed tomography (right) showing patchy consolidations with ground glass opacities involving both lung fields suggestive of an organizing pneumonia pattern

Joint involvement

Arthralgia and Arthritis are seen in 50–80% patients with anti-MDA5 DM. Notably the phenotype is similar to Rheumatoid Arthritis with a bilateral, symmetric distribution and small joint involvement. However, erosions are infrequent on conventional radiographs [46].

Lung

ILD is the most important clinical feature seen in 60–100% of patients, with a rapidly progressive phenotype reported in over 40% (20–75%) cases [44, 49, 51]. Anti-MDA5 DM has a 20 fold higher odds for development of RP ILD as compared to MDA5 negative DM and it is the most important factor predicting survival [9, 44, 49]. RP ILD presents with worsening dyspnea and cough, with radiographic deterioration causing hypoxia within 3 months from respiratory symptom onset [7, 51].

Muscle

Anti-MDA5 antibodies were originally described in a series of patients with CADM [8] with CADM occurring in over 80% of Japanese anti-MDA5 DM patients. However, in cohorts from the USA, most occurred in patients with classic DM, although the association with CADM was retained [8, 49, 57, 58].

Malignancy

Although most studies describe a protective effect of ILD and anti-MDA5 antibodies against cancer [4, 59, 60], malignancy has been described in 4–6% of patients with anti-MDA5 DM in Japanese and French studies. Contrary to previous reports, one Spanish anti-MDA5 DM study described a higher rate of cancer (4/14 cases, 28%) with risk of breast, ovarian and lung cancer.

Other systemic features

Fever, fatigue and constitutional symptoms are also common, occurring in 30–40% of these patients [44, 46, 50, 51].

Clinical phenotype in children with anti-MDA5 DM

The prevalence of anti-MDA5 DM in a large British cohort of JDM was 7% with a predominance of ulcerative skin disease, oral ulcers and arthritis, with ILD affecting 20% of individuals, none of them exhibiting the RP phenotype. CADM was seen in 12% of anti-MDA5 children, which was significantly greater than the anti-MDA5 antibody-negative group. Interestingly, the response to treatment was better than in the anti-MDA5-negative DM group, thus it may represent a milder subgroup in children. An increased association of ILD was seen with coexistent anti-Ro52 antibodies (70% vs 10% had ILD among patients with anti-MDA5 JDM) in an American cohort of JDM but RP ILD was uncommon [61]. Whereas, in East Asian cohorts over 1/3rd of JDM are constituted by anti-MDA5 DM with RP ILD seen in over half of them [7, 62, 63]. There were few anti-MDA5-positive JDM subjects in the Indian cohorts described, though the phenotype was akin to that described in the western literature [64]. A recent French multicenter study identified 13 patients with Juvenile myositis and positive anti-MDA5 antibodies, and this group was constituted equally by Juvenile Dermatomyositis (JDM) and Juvenile Overlap Myositis. They confirmed the presence of ulcerative skin disease and arthritis in frequencies similar to those previously reported; in addition, they identified that a lupus-like rash was present in half of the subjects, and aseptic abscesses in 20% [40].

Complications

Pneumomediastinum is a life-threatening complication reported in up to 15% of patients with anti-MDA5 DM and ILD, as compared to 2% in DM/PM. It is associated with a worse survival (mortality of 60% vs 37% in those without pneumomediastinum) especially in those ventilated using noninvasive pressure ventilation. Thus, in those requiring mechanical ventilation, invasive ventilation is suggested as soon pneumomediastinum is diagnosed. High-flow nasal oxygen merits further exploration in the setting of pneumomediastinum [65, 66]. The presence of cutaneous ulcers was associated with an increased odds (1.1–3.1) of pneumomediastinum in a multivariable analysis of a Chinese study that described predictors of pneumomediastinum in the setting of anti-MDA5 DM [67].

Another complication that is being reported more frequently with this type of DM is Macrophage Activation Syndrome (MAS) as described in case reports from Japan. The recent depictions of transaminitis in anti-MDA5 DM due to involvement of the liver may be a surrogate for extramedullary hemophagocytosis which merits further exploration [68, 69].

Diagnosis

A high index of suspicion for anti-MDA5DM should be considered in patients presenting with the following constellation of symptoms:

-

1.

Middle-aged female, CADM, skin rash with acute onset of respiratory symptoms;

-

2.

Middle-aged female with skin rash, arthritis and chronic respiratory symptoms;

-

3.

Middle-aged male, classic DM rash, muscle weakness, Raynaud’s phenomenon with cutaneous ulceration;

-

4.

Children with classic DM rash, ulcerative skin disease, ILD with or without muscle weakness.

The most important scenario in which a rapid diagnosis of anti-MDA5 DM has critical implications is the case of patients presenting with RP ILD. Acute interstitial pneumonitis can have a broad differential diagnosis even in the absence of obvious muscle involvement. Subtle rashes should be actively looked for as important clues to the otherwise elusive diagnosis. Although Rheumatologists may be better aware of this entity, it poses a significant diagnostic challenge for pulmonologists and intensivists who may be the primary contact physicians for such cases who rapidly deteriorate with high requirements of oxygen and intensive care support [70]. While ruling out other differentials such as viral pneumonitis, atypical bacterial pneumonia, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis, an asymptomatic elevation of muscle enzymes, cytoplasmic ANA pattern, and anti-MDA5 antibodies may be specifically looked for. In a recent multicenter French study, 36% of 47 IMIM admitted in the Intensive Care Unit with acute respiratory failure had no extrapulmonary feature (40% being anti-MDA5 DM). Timely identification is crucial for the reduction of mortality rates [71].

Anti-MDA5 antibody can be detected using IP (gold standard), line immunoassay or ELISA with a good agreement amongst the assays [5, 13, 72]. Associated Ro-52 antibodies are described in up to 60% of patients, and may pose a greater risk for RP ILD and cutaneous vasculopathy [48,49,50, 73, 74].

Screening for ILD should be done using HRCT of the chest, common findings being ground glass opacities (GGO), non-septal linear or plate-like opacities and interlobular septal thickening with absence of intralobular reticular opacities, bronchiectasis and honeycombing. The predominant patterns have been described as lower GGO and random GGO seen in over 80% of cases which corresponds to an organizing pneumonia type of ILD. The classic Atoll sign in patients with organizing pneumonia is nonspecific and may be seen in tuberculosis and fungal infections. Thus, a radiological picture suggestive of organizing pneumonia should a prompt consideration of a diagnosis of IMIM when work up for infections is negative. Elevated ferritin levels above 1000 ng/ml are predictive of lower lung predominant GGOs with an odds of 12 which in turn are predictive of a RP course [75, 76] (Fig. 5).

A European study described distinct histopathological features of anti-MDA5 DM as compared to classical DM. Absence of perifascicular fiber atrophy, characteristic vasculopathy, or important perivascular inflammation with lower IFN score was observed with overall minimal inflammatory changes on histopathology. Nitric oxide synthase 2-positive muscle fibers were seen only in this subset, which colocalized with markers of sarcolemmal regeneration and thus might have a protective effect [6, 77].

A recent study described the use of nail fold capillaroscopy to study the capillary architecture. Compared to ASSD, patients with anti-MDA5 DM showed greater scores for microhemorrhages and capillary disorganization representative of severe cutaneous vasculopathy and the scores further correlated with total lung fibrosis and ILD-related death [78].

Biomarkers

Numerous biomarkers have been evaluated to predict mortality and assess response to treatment (Table 3). Ferritin is widely available and elevated levels (> 1000 ng/ml) are predictive of extensive lung involvement and a poor prognosis. It can be used as a marker to initiate intensive immunosuppression and to judge the response to therapy similar to its role in MAS [79].

Declining titers of anti-MDA5 antibody was associated with survival and re-increase in the levels (by > 50 index from its level during remission) correlated with relapse of disease [23]. However, it is pertinent to note that although a mere absence or presence of antibody correlates with disease, titers of anti-MDA5 antibody at baseline did not show any correlation with severity of manifestations or death [49].

A recent Japanese study identified hepatic dysfunction disproportionate to muscle involvement (defined as disproportionate rise in alanine transaminase as compared to creatine phosphokinase levels) in anti-MDA5 DM. In 50 patients of DM, all 10 with anti-MDA5 DM had liver dysfunction and a subsequent liver biopsy done in four of them showed steatosis and ballooning of hepatocytes. The liver dysfunction correlated with KL-6 levels, but not with presence of ILD. Thus, hepatic dysfunction might represent an extramuscular involvement in this subset [80].

Four-gene interferon signature, serum interferon levels and interferon expression in cutaneous biopsies are elevated in both adults and children with anti-MDA5 IMIM and correlate with response to treatment [40].

Elevated ferritin (> 828 ng/ml), C-reactive protein (CRP, > 1 mg/dL), KL-6 (> 1000 ng/dL), decreased T helper subsets and serum CD 206 identify patients with a poor prognosis and at high risk for mortality. These markers return to normalcy 3–6 months following effective treatment and thus may be useful to guide treatment and monitor for relapses [81, 82].

Treatment

MDA5 DM presenting with RP ILD represents the most severe and difficult to treat form of the disease and mandates intensive immunosuppression. Pulse corticosteroids (15–20 mg/kg/dose) for 3–5 days followed by oral corticosteroids (1 mg/kg) along with immunosuppressants are preferred for induction (Table 4). There is a dearth of clinical studies evaluating the best line of treatment. The current evidence base largely stems from observational studies and case reports. Steroid monotherapy and standard immunosuppressants like methotrexate and azathioprine have shown poor results in RP ILD [14].

Recent retrospective series suggest benefit from upfront combination therapy [83,84,85]. Subsequently, in a prospective study of 29 anti-MDA5 DM Japanese patients with RP ILD, a combination of steroids, tacrolimus and cyclophosphamide (iv CYC) was administered upfront. The 6-month survival rates were significantly better for the combination group (89% vs 33%) as compared with a historical cohort which received step-up immunosuppression. A similar rate of serious infections was recorded in both groups, except for higher Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation in the former (85% vs 35%) [86]. All the three deaths in the combination group were due to worsening ILD. Prophylaxis for pneumocystis carinii pneumonia was given to all, however, CMV prophylaxis was not. Although, there is lack of data for use of CMV prophylaxis in IMIM, there might be a rationale to adopt this measure in the setting of upfront combined immunosuppression. Patients with ILD and anti-MDA5 antibodies are at a higher risk of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and prophylaxis should considered for these patients [61]. When the use of calcineurin inhibitors is not feasible, Mycophenolate Mofetil and Rituximab have been used, albeit unsuccessfully in some case reports [87, 88].

In refractory cases, plasma exchange, polymyxin B hemoperfusion and IVIG exhibit a variable response [89,90,91]. Of these, the best results have been seen with plasma exchange with improved 1-year survival up to 100% in some series. Plasma exchange has been used after unsuccessful combination therapy of immunosuppressants, ranging from 3 to 14 sessions per patient [92].

Another class of drugs that has been recently explored are the JAK inhibitors which may have specific benefits in this condition. JAK inhibitors directly interfere with interferon production, which may result in abrogation of the cytokine storm, in a quick and predictable manner unlike most other immunosuppressants which typically take 2–4 weeks to take effect. Lost time may result in a declining foothold on success of survival in a disorder of such severity. Tofacitinib use has led to an improved survival, reduction in ferritin levels and CT scores in case reports [43, 93]. Anakinra has been used successfully as well [94].

The antifibrotic pirfenidone yielded an insignificant effect on the survival in RP ILD in a prospective study albeit with suggested benefit in the subset with a subacute onset of ILD [95].

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxidation as a bridge therapy awaiting response to immunosuppressants or to a lung transplant may be used in equipped centers. There are 8 reported cases of lung transplant with an overall survival rate of 75% over 7 months to 12 years [96, 97].

Cutaneous vasculopathy also represents a severe form of the disease with requirement of immunosuppressants, IVIG along with vasodilators (Phosphodiesterase inhibitors and calcium channel blockers) and agents that improve peripheral circulation (Pentoxiphylline, at times hyperbaric oxygen) for which there is evidence in the form of anecdotal reports [98].

Prognosis

Older age (> 60 years), male gender, fever, elevated CRP more than 1 mg/dL and oxygen saturation less than 95% are associated with poor prognosis and mortality [99, 100] Sato et al. derived a prediction model in a large cohort of Japanese patients of myositis-ILD using a composite of age, CRP, oxygen saturation and anti-MDA5 antibodies for prediction of mortality. Another risk model, ‘FLAIR’, using Ferritin, LDH, anti-MDA5 Antibody, CT Imaging score, and RP ILD has been developed to predict survival in patients with CADM/ILD [101].

Conclusion

Anti-MDA5 DM is recently identified subtype of myositis characteristically associated with RP-ILD and unique cutaneous features. The etiopathogenesis is hypothetically linked to an unidentified viral trigger on the background of genetic predisposition culminating in an acquired type I interferonopathy. The clinical phenotype is highly varied in different ethnicities. The recent description of new cohorts of patients with a wider range of presenting clinical features has expanded the anti-MDA5 DM disease spectrum. Awareness of the condition and its potential manifestations is key to early detection and improved survival. RP ILD is the major determinant of survival, treatment being largely empiric and based on observational studies, with early and aggressive combined immunosuppression showing potential in recent reports.

References

Bohan A, Peter JB (1975) Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med 292:344–347. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197502132920706

Bohan A, Peter JB (1975) Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med 292:403–407. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197502202920807

McHugh NJ, Tansley SL (2018) Autoantibodies in myositis. Nature reviews. Rheumatology 14:290–302. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2018.56

Betteridge Z, Tansley S, Shaddick G et al (2019) Frequency, mutual exclusivity and clinical associations of myositis autoantibodies in a combined European cohort of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy patients. J Autoimmun 101:48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2019.04.001

Sato S, Murakami A, Kuwajima A et al (2016) Clinical utility of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 autoantibodies. PLoS ONE 11:e0154285. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154285

Yasin SA, Schutz PW, Deakin CT et al (2019) Histological heterogeneity in a large clinical cohort of juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: analysis by myositis autoantibody and pathological features. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 45:495–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12528

Kobayashi N, Takezaki S, Kobayashi I et al (2015) Clinical and laboratory features of fatal rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease associated with juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 54:784–791. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keu385

Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M et al (2005) Autoantibodies to a 140-kd polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 52:1571–1576. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21023

Chen Z, Cao M, Plana MN et al (2013) Utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody measurement in identifying patients with dermatomyositis and a high risk for developing rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease: a review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 65:1316–1324. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21985

Kurtzman DJB, Vleugels RA (2018) Anti-melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5 (MDA5) dermatomyositis: a concise review with an emphasis on distinctive clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol 78:776–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.010

Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Aggarwal R (2018) Anti-MDA5 antibody spectrum in western world. Curr Rheumatol Rep 20:78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-018-0798-1

Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, Kitas GD (2011) Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int 31:1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-1999-3

Mahler M, Betteridge Z, Bentow C et al (2019) Comparison of three immunoassays for the detection of myositis specific antibodies. Front Immunol 10:848. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00848

Tokiyama K, Tagawa H, Yokota E et al (1990) Two cases of amyopathic dermatomyositis with fatal rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonitis. Ryumachi [Rheumatism] 30:204–209 (discussion 209–211)

Nanke Y, Tateisi M, Yamagata H et al (2000) A case of amyopathic dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonia. Ryumachi [Rheumatism] 40:705–710

Sato S, Hoshino K, Satoh T et al (2009) RNA helicase encoded by melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 is a major autoantigen in patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: association with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 60:2193–2200. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24621

Kang D, Gopalkrishnan RV, Wu Q et al (2002) mda-5: an interferon-inducible putative RNA helicase with double-stranded RNA-dependent ATPase activity and melanoma growth-suppressive properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:637–642. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.022637199

Chen Z, Cao M, Plana MN et al (2013) Utility of anti-melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5 antibody measurement in identifying patients with dermatomyositis and a high risk for developing rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease: a review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 65:1316–1324. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21985

Christensen ML, Pachman LM, Schneiderman R et al (1986) Prevalence of coxsackie b virus antibodies in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 29:1365–1370. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780291109

Chevrel G, Calvet A, Belin V, Miossec P (2000) Dermatomyositis associated with the presence of parvovirus B19 DNA in muscle. Rheumatology 39:1037–1039. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/39.9.1037

Nakashima R, Imura Y, Kobayashi S et al (2010) The RIG-I-like receptor IFIH1/MDA5 is a dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen identified by the anti-CADM-140 antibody. Rheumatology 49:433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep375

Dias Junior AG, Sampaio NG, Rehwinkel J (2019) A balancing act: MDA5 in antiviral immunity and autoinflammation. Trends Microbiol 27:75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2018.08.007

Matsushita T, Mizumaki K, Kano M et al (2017) Antimelanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 antibody level is a novel tool for monitoring disease activity in rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease with dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol 176:395–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14882

Wang Y, Du G, Zhang G et al (2020) Similarities and differences between severe COVID-19 pneumonia and anti-MDA-5-positive dermatomyositis-associated rapidly progressive interstitial lung diseases: a challenge for the future. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218594

Giannini M, Ohana M, Nespola B et al (2020) Similarities between COVID-19 and anti-MDA5 syndrome: what can we learn for better care? Eur Respir J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01618-2020

De Lorenzis E, Natalello G, Gigante L et al (2020) What can we learn from rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease related to anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis in the management of COVID-19? Autoimmun Rev 19:102666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102666

Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: an autopsy series from New Orleans—The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanres/article/PIIS2213-2600(20)30243-5/fulltext. Accessed 12 Nov 2020

Gupta L, Chinoy H (2020) Monitoring disease activity and damage in adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Curr Opin Rheumatol 32:553–561. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000749

Gupta L, Misra DP, Agarwal V et al (2020) Response to: ‘telerheumatology in COVID-19 era: a study from a psoriatic arthritis cohort’ by Costa et al. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217953

Naveen R, Sundaram TG, Agarwal V, Gupta L (2020) Teleconsultation experience with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: a prospective observational cohort study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04737-8

Gupta L, Lilleker JB, Agarwal V et al (2020) COVID-19 and myositis—unique challenges for patients. Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa610

Gono T, Kawaguchi Y, Kuwana M et al (2012) Brief report: association of HLA-DRB1*0101/*0405 with susceptibility to anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis in the Japanese population. Arthritis Rheum 64:3736–3740. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34657

Chen Z, Wang Y, Kuwana M et al (2017) HLA-DRB1 alleles as genetic risk factors for the development of anti-MDA5 antibodies in patients with dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 44:1389–1393. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.170165

Rothwell S, Chinoy H, Lamb JA et al (2019) Focused HLA analysis in Caucasians with myositis identifies significant associations with autoantibody subgroups. Ann Rheum Dis 78:996–1002. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215046

Kochi Y, Kamatani Y, Kondo Y et al (2018) Splicing variant of WDFY4 augments MDA5 signalling and the risk of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis 77:602–611. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212149

Muro Y, Sugiura K, Hoshino K et al (2011) Epidemiologic study of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis and anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibodies in central Japan. Arthritis Res Ther 13:R214. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3547

Nishina N, Sato S, Masui K et al (2020) Seasonal and residential clustering at disease onset of anti-MDA5-associated interstitial lung disease. RMD Open 6:e001202. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001202

Sun WC, Sun YC, Lin H et al (2012) Dysregulation of the type I interferon system in adult-onset clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis has a potential contribution to the development of interstitial lung disease. Br J Dermatol 167:1236–1244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11145.x

Bai J, Wu C, Zhong D et al (2020) Hierarchical cluster analysis of cytokine profiles reveals a cutaneous vasculitis-associated subgroup in dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05339-2

Melki I, Devilliers H, Gitiaux C et al (2020) Anti-MDA5 juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: a specific subgroup defined by differentially enhanced interferon-α signalling. Rheumatology 59:1927–1937. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez525

Kim H, Gunter-Rahman F, McGrath JA et al (2020) Expression of interferon-regulated genes in juvenile dermatomyositis versus Mendelian autoinflammatory interferonopathies. Arthritis Res Ther 22:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-020-02160-9

de Jesus AA, Hou Y, Brooks S et al (2020) Distinct interferon signatures and cytokine patterns define additional systemic autoinflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest 130:1669–1682. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129301

Chen Z, Wang X, Ye S (2019) Tofacitinib in amyopathic dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med 381:291–293. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1900045

Koga T, Fujikawa K, Horai Y et al (2012) The diagnostic utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody testing for predicting the prognosis of Japanese patients with DM. Rheumatology 51:1278–1284. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ker518

Gono T, Kawaguchi Y, Satoh T et al (2010) Clinical manifestation and prognostic factor in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-associated interstitial lung disease as a complication of dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 49:1713–1719. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keq149

Hall JC, Casciola-Rosen L, Samedy L-A et al (2013) Anti-melanoma differentiation–associated protein 5–associated dermatomyositis: expanding the clinical spectrum. Arthritis Care Res 65:1307–1315. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21992

Ceribelli A, Fredi M, Taraborelli M et al (2014) Prevalence and clinical significance of anti-MDA5 antibodies in European patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 32(6):891–897

Platteel ACM, Wevers BA, Lim J et al (2019) Frequencies and clinical associations of myositis-related antibodies in The Netherlands: a one-year survey of all Dutch patients. J Transl Autoimmun 2:100013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtauto.2019.100013

Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Sato S et al (2017) Antimelanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody: expanding the clinical spectrum in north American patients with dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 44:319–325. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160682

Labrador-Horrillo M, Martinez MA, Selva-O’Callaghan A et al (2014) Anti-MDA5 antibodies in a large Mediterranean population of adults with dermatomyositis. J Immunol Res 2014:290797. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/290797

Allenbach Y, Uzunhan Y, Toquet S et al (2020) Different phenotypes in dermatomyositis associated with anti-MDA5 antibody. Neurology 95:e70–e78. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009727

Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J et al (2011) The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 65:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2010.09.016

Narang NS, Casciola-Rosen L, Li S et al (2015) Cutaneous ulceration in dermatomyositis: association with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibodies and interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Care Res 67:667–672. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22498

Cao H, Pan M, Kang Y et al (2012) Clinical manifestations of dermatomyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis patients with positive expression of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody. Arthritis Care Res 64:1602–1610. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21728

Ono N, Kai K, Maruyama A et al (2020) The relationship between type 1 IFN and vasculopathy in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis patients. Rheumatology 59:918. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa033

Rathore U, Haldule S, Gupta L (2020) Psoriasiform rashes as the first manifestation of anti-MDA5 associated myositis. Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa821

Fujikawa K, Kawakami A, Kaji K et al (2009) Association of distinct clinical subsets with myositis-specific autoantibodies towards anti-155/140-kDa polypeptides, anti-140-kDa polypeptides, and anti-aminoacyl tRNA synthetases in Japanese patients with dermatomyositis: a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Scand J Rheumatol 38:263–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009740802687455

Kang EH, Nakashima R, Mimori T et al (2010) Myositis autoantibodies in Korean patients with inflammatory myositis: Anti-140-kDa polypeptide antibody is primarily associated with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease independent of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11:223. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-11-223

Liu Y, Xu L, Wu H et al (2018) Characteristics and predictors of malignancy in dermatomyositis: analysis of 239 patients from northern China. Oncol Lett 16:5960–5968. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.9409

Hoshino K, Muro Y, Sugiura K et al (2010) Anti-MDA5 and anti-TIF1-gamma antibodies have clinical significance for patients with dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 49:1726–1733. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keq153

Sabbagh S, Pinal-Fernandez I, Kishi T et al (2019) Anti-Ro52 autoantibodies are associated with interstitial lung disease and more severe disease in patients with juvenile myositis. Ann Rheum Dis 78:988–995. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-215004

Kobayashi I, Okura Y, Yamada M et al (2011) Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody is a diagnostic and predictive marker for interstitial lung diseases associated with juvenile dermatomyositis. J Pediatri 158:675–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.11.033

Iwata N, Nakaseko H, Kohagura T et al (2019) Clinical subsets of juvenile dermatomyositis classified by myositis-specific autoantibodies: experience at a single center in Japan. Mod Rheumatol 29:802–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2018.1511025

Hussain A, Rawat A, Jindal AK et al (2017) Autoantibodies in children with juvenile dermatomyositis: a single centre experience from north-west India. Rheumatol Int 37:807–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-017-3707-4

Zhou M, Ye Y, Yan N et al (2020) Noninvasive positive pressure ventilator deteriorates the outcome of pneumomediastinum in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol 39:1919–1927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04918-2

Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi A, Itai M et al (2019) Clinical features of patients with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene-5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis complicated by spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Clin Rheumatol 38:3443–3450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04729-5

Ma X, Chen Z, Hu W et al (2016) Clinical and serological features of patients with dermatomyositis complicated by spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Clin Rheumatol 35:489–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-3001-3

Kishida D, Sakaguchi N, Ueno K et al (2020) Macrophage activation syndrome in adult dermatomyositis: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int 40:1151–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04590-9

Honda M, Moriyama M, Kondo M et al (2020) Three cases of autoimmune-associated haemophagocytic syndrome in dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 autoantibody. Scand J Rheumatol 49:244–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009742.2019.1653493

Gupta L, Muhammed H, Naveen R et al (2020) Insights into the knowledge, attitude and practices for the treatment of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy from a cross-sectional cohort survey of physicians. Rheumatol Int 40:2047–2055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04695-1

Vuillard C, Pineton de Chambrun M, de Prost N et al (2018) Clinical features and outcome of patients with acute respiratory failure revealing anti-synthetase or anti-MDA-5 dermato-pulmonary syndrome: a French multicenter retrospective study. Ann Intensive Care. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-018-0433-3

Gono T, Okazaki Y, Murakami A, Kuwana M (2019) Improved quantification of a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit for measuring anti-MDA5 antibody. Mod Rheumatol 29:140–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2018.1452179

Xing X, Li A, Li C (2020) Anti-Ro52 antibody is an independent risk factor for interstitial lung disease in dermatomyositis. Respir Med 172:106134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106134

Temmoku J, Sato S, Fujita Y et al (2019) Clinical significance of myositis-specific autoantibody profiles in Japanese patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015578

Tanizawa K, Handa T, Nakashima R et al (2011) HRCT features of interstitial lung disease in dermatomyositis with anti-CADM-140 antibody. Respir Med 105:1380–1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2011.05.006

Zuo Y, Ye L, Liu M et al (2020) Clinical significance of radiological patterns of HRCT and their association with macrophage activation in dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 59:2829–2837. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa034

Allenbach Y, Leroux G, Suárez-Calvet X et al (2016) Dermatomyositis with or without anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibodies: common interferon signature but distinct NOS2 expression. Am J Pathol 186:691–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.11.010

Wakura R, Matsuda S, Kotani T et al (2020) The comparison of nailfold videocapillaroscopy findings between anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody and anti-aminoacyl tRNA synthetase antibody in patients with dermatomyositis complicated by interstitial lung disease. Sci Rep 10:15692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72752-7

Gono T, Kawaguchi Y, Ozeki E et al (2011) Serum ferritin correlates with activity of anti-MDA5 antibody-associated acute interstitial lung disease as a complication of dermatomyositis. Mod Rheumatol 21:223–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10165-010-0371-x

Nagashima T, Kamata Y, Iwamoto M et al (2019) Liver dysfunction in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-positive patients with dermatomyositis. Rheumatol Int 39:901–909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04255-2

Nishioka A, Tsunoda S, Abe T et al (2019) Serum neopterin as well as ferritin, soluble interleukin-2 receptor, KL-6 and anti-MDA5 antibody titer provide markers of the response to therapy in patients with interstitial lung disease complicating anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Mod Rheumatol 29:814–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2018.1548918

Chen F, Wang D, Shu X et al (2012) Anti-MDA5 antibody is associated with A/SIP and decreased T cells in peripheral blood and predicts poor prognosis of ILD in Chinese patients with dermatomyositis. Rheumatol Int 32:3909–3915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-2323-y

Nara M, Komatsuda A, Omokawa A et al (2014) Serum interleukin 6 levels as a useful prognostic predictor of clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Mod Rheumatol 24:633–636. https://doi.org/10.3109/14397595.2013.844390

Nakashima R, Hosono Y, Mimori T (2016) Clinical significance and new detection system of autoantibodies in myositis with interstitial lung disease. Lupus 25:925–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203316651748

Matsuda KM, Yoshizaki A, Kuzumi A et al (2020) Combined immunosuppressive therapy provides favorable prognosis and increased risk of cytomegalovirus reactivation in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis. J Dermatol 47:483–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.15274

Tsuji H, Nakashima R, Hosono Y et al (2020) Multicenter prospective study of the efficacy and safety of combined immunosuppressive therapy with high-dose glucocorticoid, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide in interstitial lung diseases accompanied by anti-melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol 72:488–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41105

Hayashi M, Aoki A, Asakawa K et al (2017) Cytokine profiles of amyopathic dermatomyositis with interstitial lung diseases treated with mycophenolate. Respirol Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcr2.235

Mao M-M, Xia S, Guo B-P et al (2020) Ultra-low dose rituximab as add-on therapy in anti-MDA5-positive patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis associated ILD. Respir Med 172:105983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105983

Mrosak J, Banasiak K, Edelheit B et al (2019) Polymyxin-B hemoperfusion as a novel treatment for rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease in a pediatric patient diagnosed with anti-MDA5 juvenile dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001191

Abe Y, Kusaoi M, Tada K et al (2020) Successful treatment of anti-MDA5 antibody-positive refractory interstitial lung disease with plasma exchange therapy. Rheumatology 59:767–771. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez357

Shirakashi M, Nakashima R, Tsuji H et al (2020) Efficacy of plasma exchange in anti-MDA5-positive dermatomyositis with interstitial lung disease under combined immunosuppressive treatment. Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa123

T S, M M, Y M, et al (2020) Anti-MDA-5 antibody-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease treated with therapeutic plasma exchange: a case series. J Clinical Apher. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32823371/. Accessed 26 Oct 2020

Ishikawa Y, Kasuya T, Fujiwara M, Kita Y (2020) Tofacitinib for recurrence of antimelanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis after remission: a case report. Medicine 99:e21943. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000021943

Groh M, Rogowska K, Monsarrat O et al (2015) Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist for refractory anti-MDA5 clinically amyopathic dermatomyopathy. Clin Exp Rheumatol 33:904–905

Li T, Guo L, Chen Z et al (2016) Pirfenidone in patients with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease associated with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Sci Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33226

Huang K, Vinik O, Shojania K et al (2019) Clinical spectrum and therapeutics in Canadian patients with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5)-positive dermatomyositis: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int 39:1971–1981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04398-2

Romero-Bueno F, Diaz Del Campo P, Trallero-Araguás E et al (2020) Recommendations for the treatment of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis-associated rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 50:776–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.03.007

Jeter J, Wolf EG, Richards M, Hill E (2020) Successful treatment of anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis associated cutaneous digital pulp ulcerations with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Clin Rheumatol 26:e266–e267. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001114

Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi A, Onuki Y et al (2020) Clinical features of dermatomyositis associated with anti-MDA5 antibodies by age. Mod Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2020.1740400

Sato S, Masui K, Nishina N et al (2018) Initial predictors of poor survival in myositis-associated interstitial lung disease: a multicentre cohort of 497 patients. Rheumatology 57:1212–1221. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key060

Lian X, Zou J, Guo Q et al (2020) Mortality risk prediction in amyopathic dermatomyositis associated with interstitial lung disease: the FLAIR model. Chest 158:1535–1545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.057

Gono T, Sato S, Kawaguchi Y et al (2012) Anti-MDA5 antibody, ferritin and IL-18 are useful for the evaluation of response to treatment in interstitial lung disease with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 51:1563–1570. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kes102

Moghadam-Kia S, Oddis CV, Sato S et al (2016) Anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 is associated with rapidly progressive lung disease and poor survival in us patients with amyopathic and myopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Care Res 68:689–694. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22728

Mehta P, Agarwal V, Gupta L (2021) High early mortality in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: results from the inception cohort at a tertiary care center in northern India. Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab001

Tansley SL, Betteridge ZE, Gunawardena H et al (2014) Anti-MDA5 autoantibodies in juvenile dermatomyositis identify a distinct clinical phenotype: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 16:R138. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4600

Mamyrova G, Kishi T, Shi M et al (2020) Anti-MDA5 autoantibodies associated with juvenile dermatomyositis constitute a distinct phenotype in north America. Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa429

Ye Y, Fu Q, Wang R et al (2019) Serum KL-6 level is a prognostic marker in patients with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis associated with interstitial lung disease. J Clin Lab Anal 33:e22978. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.22978

Kaieda S, Gono T, Masui K et al (2020) Evaluation of usefulness in surfactant protein D as a predictor of mortality in myositis-associated interstitial lung disease. PLoS ONE 15:e0234523. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234523

Peng Q-L, Zhang Y-M, Liang L et al (2020) A high level of serum neopterin is associated with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease and reduced survival in dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Immunol 199:314–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/cei.13404

Horiike Y, Suzuki Y, Fujisawa T et al (2019) Successful classification of macrophage-mannose receptor CD206 in severity of anti-MDA5 antibody positive dermatomyositis associated ILD. Rheumatology 58:2143–2152. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez185

Matsushita T, Kobayashi T, Kano M et al (2019) Elevated serum B-cell activating factor levels in patients with dermatomyositis: association with interstitial lung disease. J Dermatol 46:1190–1196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.15117

Zhang SH, Zhao Y, Xie QB et al (2019) Aberrant activation of the type I interferon system may contribute to the pathogenesis of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol 180:1090–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16917

Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M (2013) Limitations of a single-point evaluation of anti-MDA5 antibody, ferritin, and IL-18 in predicting the prognosis of interstitial lung disease with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol 32:395–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2142-x

Kameda H, Nagasawa H, Ogawa H et al (2005) Combination therapy with corticosteroids, cyclosporin A, and intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide for acute/subacute interstitial pneumonia in patients with dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 32:1719–1726

So H, Wong VTL, Lao VWN et al (2018) Rituximab for refractory rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease related to anti-MDA5 antibody-positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol 37:1983–1989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4122-2

Tokunaga K, Hagino N (2017) Dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease treated with rituximab: a report of 3 cases in Japan. Intern Med 56:1399–1403. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7956

Zou J, Li T, Huang X et al (2014) Basiliximab may improve the survival rate of rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonia in patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibody. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1591–1593. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205278

Saito T, Mizobuchi M, Miwa Y et al (2020) Anti-MDA-5 antibody-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease treated with therapeutic plasma exchange: a case series. J Clin Apher. https://doi.org/10.1002/jca.21833

Okabayashi H, Ichiyasu H, Hirooka S et al (2017) Clinical effects of direct hemoperfusion using a polymyxin B-immobilized fiber column in clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis-associated rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonias. BMC Pulm Med 17:134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0479-2

Takada T, Aoki A, Asakawa K et al (2015) Serum cytokine profiles of patients with interstitial lung disease associated with anti-CADM-140/MDA5 antibody positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Respir Med 109:1174–1180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2015.07.004

Ichiyasu H, Sakamoto Y, Yoshida C et al (2017) Rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease due to anti-MDA-5 antibody-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis complicated with cervical cancer: successful treatment with direct hemoperfusion using polymyxin B-immobilized fiber column therapy. Respir Med Case Rep 20:51–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2016.11.015

Teruya A, Kawamura K, Ichikado K et al (2013) Successful polymyxin B hemoperfusion treatment associated with serial reduction of serum anti-CADM-140/MDA5 antibody levels in rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease with amyopathic dermatomyositis. Chest 144:1934–1936. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-0186

Kurasawa K, Arai S, Namiki Y et al (2018) Tofacitinib for refractory interstitial lung diseases in anti-melanoma differentiation-associated 5 gene antibody-positive dermatomyositis. Rheumatology 57:2114–2119. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key188

Vuillard C, Pineton de Chambrun M, de Prost N et al (2018) Clinical features and outcome of patients with acute respiratory failure revealing anti-synthetase or anti-MDA-5 dermato-pulmonary syndrome: a French multicenter retrospective study. Ann Intensive Care 8:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-018-0433-3

Funding

PMM is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) University College London Hospitals (UCLH) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PM and LG were involved in the conceptualization and methodology. PM was involved in writing of the original draft and LG and PMM were involved in manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

PM and LG report no conflicts of interest/competing interests. PMM has received consulting/speaker’s fees from Abbvie, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Orphazyme, Pfizer, Roche and UCB, all unrelated to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mehta, P., Machado, P.M. & Gupta, L. Understanding and managing anti-MDA 5 dermatomyositis, including potential COVID-19 mimicry. Rheumatol Int 41, 1021–1036 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04819-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04819-1