Abstract

Background

Preoperative anxiety is associated with increased use of anesthetics and poorer postoperative outcomes. However, the prevalence of preoperative anxiety has not been characterized in Chinese patients. In this study, we aimed to estimate the overall prevalence of preoperative anxiety in Chinese adult patients and to explore the sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with preoperative anxiety in China.

Methods

This study was a multicenter cross-sectional study conducted at 32 tertiary referral centers in China from September 1 to October 31, 2020. Adult patients scheduled for elective surgery were evaluated by the 7-item Perioperative Anxiety Scale (PAS-7) for preoperative anxiety after entrance to the operating zone.

Results

A total of 5191 patients were recruited, and 5018 of them were analyzed. The prevalence of preoperative anxiety measured by PAS-7 was 15.8% (95% CI 14.8 to 16.9%). Multivariable analyses showed female sex, younger age, non-retired, first in a lifetime surgery, surgery of higher risk, and poorer preoperative sleep were associated with higher prevalence of preoperative anxiety.

Conclusions

Preoperative anxiety was relatively common (prevalence of 15.8%) among adult Chinese patients undergoing elective surgeries. Further studies are needed using suitable assessment tools to better characterize preoperative anxiety, and additional focus should be placed on perioperative education and intervention, especially in primary hospitals.

Trial registration

This study was registered prospectively at www.chictr.org.cn (ChiCTR1900027639) on November 22, 2019.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anxiety is common among perioperative patients [1,2,3,4]. Anxiety involves both in negative psychological expectations and physical changes toward future events [5]. In addition to contributing to an unpleasant perioperative experience, preoperative anxiety has been associated with increased use of anesthetics [6], severer postoperative pain [7], cognitive impairment [8], higher risk of postoperative complications and deaths [9], and poorer long-term quality of life and survival [10].

Approximately 40 million patients undergo surgical procedures annually in China [11], but the prevalence of preoperative anxiety has not been fully investigated. A few small-scale studies involving several hundred patients reported prevalence of preoperative anxiety ranging from 11 to 89% [8, 12,13,14]. However, these studies were mainly single-center studies involving only specific types of surgeries using various anxiety assessment tools. The large degree of heterogeneity among studies has precluded generalization of the results to other patient population. Therefore, a nationwide cross-sectional investigation is needed to draw a clearer picture of the existing circumstances of perioperative anxiety in China.

Multiple anxiety assessment tools have been used in clinical and research settings. However, there is no consensus assessment tool for surgical patients, and assessments are difficult to perform perioperatively. Cultural and language differences also limit the use of certain assessment tools in different countries [3, 15]. Chinese patients often do not express negative feelings directly, but rather convey their disturbed mood in the form of somatic symptoms. Therefore, somatic anxiety is an important aspect in anxiety assessments in the Chinese population.

In this study, we aimed to estimate the prevalence of preoperative anxiety in China and determine sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with preoperative anxiety.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by Research Ethics Committees at Peking Union Medical College Hospital and registered prospectively at www.chictr.org.cn (ChiCTR1900027639). Written informed consent was obtained before data collection.

Patients

This national multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted at 32 tertiary referral centers in China from September 1 to October 31, 2020. Recruitment of patients was completed using a cluster sampling strategy. Eligible centers were selected from membership institutes of Chinese Society of Anesthesiology (CSA) by the research expert committee based on geographic location, annual surgical volume, and representativeness of the general surgical population during several expert panel discussions. Patients who met all the following inclusion criteria were considered for recruitment: (1) patients undergoing elective surgery; (2) ASA classification I-III; (3) age ≥18 years; (4) capable of understanding and completing the questionnaire with assistance from medical staff; (5) informed consent obtained. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) current mental illness, disturbance of consciousness, or unable to communicate; 2) substance use disorders; (3) long-term (more than 3 months) usage of antidepressants, antianxiety medications, or other psychotropic medications; (4) could not understand, or refused to finish the questionnaire; and (5) unable to give consent, or refused to participate. Eligible patients were consecutively recruited in each center during the 2-month study period.

Questionnaire

The 7-item Perioperative Anxiety Scale (PAS-7) was used as the major assessment tool for preoperative anxiety status. The PAS-7 was specifically designed for adult Chinese surgical patients and showed good reliability and validity compared to Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale (GAD-7) [16]. The PAS-7 contains seven questions of a 5-point Likert scale (Appendix 1), with Questions No.1-4 regarding mental anxiety and Questions No.5-7 regarding somatic anxiety [16]. Patients with a PAS-7 score ≥8 were considered to have preoperative anxiety.

Data collection

At least two resident anesthesiologists in each participating center were trained to evaluate and collect patient information in a standardized manner. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were visited one day before surgery, during which informed consent was obtained and general patient information was collected. Sociodemographic information and medical conditions were collected via hospital information system and face-to-face inquiry. Surgical risk was assessed by the attending anesthesiologist according to the China Hospital Association (CHA) surgical risk evaluation form (Appendix 1) adapted from national nosocomial infections surveillance system (NNIS) risk index [17, 18]. On the day of surgery, the anxiety status of each patient was evaluated after separation from their companion. The patients were encouraged to complete the PAS-7 questionnaire in a private setting. Patients could seek help with any issues associated with the questionnaire, and standardized instructions and responses were used for assistance. An electronic data capture system was used for data collection and questionnaire distribution. After completion of survey, the database was locked and specific information was exported by an exclusive information extractor. Specially trained data inspectors oversaw the data collection process.

Statistical analysis

The raw preoperative anxiety prevalence was calculated using the number of patients diagnosed with anxiety divided by the overall number of patients. A confidence interval (CI) for prevalence of anxiety was calculated using the Agresti–Coull method [19]. Raw prevalence was also calculated in subgroups according to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. The association between preoperative anxiety and patient characteristics was analyzed using multivariable logistic regression analysis with stepwise variable selection using Akaike information criterion (AIC). Mixed-effect model analysis considering potential cluster effect from each participating center was also performed (Appendix 1). Strength of association was expressed using odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. All data were analyzed using R (version 4.0.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2020, https://www.R-project.org), and two-sided P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Sample size was determined using methods for estimating the CI of a binomial proportion. Previous reported preoperative anxiety prevalence varied across a wide range (11 to 89%) [8, 9, 12, 13, 20, 21]. We used 50% as the estimated prevalence because the sample size was largest under this estimated value. A simple random sampling method required 402 patients with 10% absolute width of lower to upper bounds of the 95%CI. Considering the cluster sampling design, we assumed a within-cluster rate of homogeneity of 0.05. The design effect was 8.45 when the number of eligible patients was 150 in each center. Thirty-two centers would have contributed a total of 4,800 patients, which was larger than 3396 (sample size determined for simple random sampling × design effect), and satisfied the requirement for the confidence accuracy. Considering possible data missing, this study planned to include 5100 patients.

Results

A total of 32 tertiary hospitals in 26 provinces participated in this national cross-sectional study, including hospitals in Anhui, Beijing, Chongqing, Fujian, Guangdong, Guizhou, Hainan, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Inner Mongolia, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Jilin, Liaoning, Ningxia, Shanxi, Shandong, Shanghai, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Tianjin, Yunnan, and Zhejiang Province (Fig. 1 and Appendix 2).

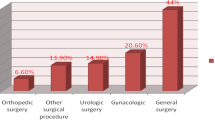

In total, 5,191 patients were recruited and 5,018 were included after data cleaning. Fifty-three patients were excluded due to missing information on anxiety assessment, 73 were excluded due to inappropriate timing of preoperative assessment, 24 were excluded due to missing PAS-7 score, and 23 patients were excluded for inappropriate surgical department. The recruitment rate was 96.7%. The mean age was 47.6 ± 14.4 years, and 59.0% were female. The majority of patients underwent surgery in the departments of general surgery (35.8%), gynecology (17.9%), and orthopedics (14.5%). Most surgeries were low risk (72.8%) and medium risk (22.4%), with only 4.8% considered high or very high risk. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

A total of 794 patients suffered from preoperative anxiety, as determined using the PAS-7 (PAS-7 score ≥ 8), revealing a prevalence of 15.8% (95% CI 14.8% to 16.9%) in adult Chinese surgical patients. The mean PAS-7 score was 4.03 ± 4.19 (median [IQR] 3.0 [1.0, 6.0]), with 3.20 ± 3.04 (median [IQR] 2.5 [1.0, 5.0]) for mental anxiety score and 0.83 ± 1.68 (median [IQR] 0.0 [0.0, 1.0]) for somatic anxiety score.

Subgroup analysis was performed based on baseline and sociodemographic characteristics (Fig. 2). This analysis showed that the prevalence of preoperative anxiety was lower in senior patients. The preoperative anxiety prevalence in the youngest group was 24.5% (95% CI 22.1% to 26.8%), and the prevalence was 10.2% (95% CI 8.5% to 11.9%) in the oldest. On average, 19.7% of female patients had preoperative anxiety while only 10.4% of male patients had preoperative anxiety. Patients with lower ASA classification were more likely to suffer from preoperative anxiety. Patients who slept well before surgery had a lower prevalence of anxiety (10.9%; 95% CI 9.6% to 12.3%) than those who slept poorly (27.9%; 95% CI 24.7% to 31.2%). Unmarried and divorced patients had a higher prevalence of preoperative anxiety. Patients with higher education experience tended to be more anxious. Retired patients were less likely to present with preoperative anxiety.

Subgroup analysis according to surgical factors was also performed (Fig. 3). The prevalence of preoperative anxiety was highest (approximately 25%) among patients undergoing cardiac surgery or obstetrics and gynecology surgery. The prevalence was lowest (10.3%; 95% CI 7.3% to 13.3%) in patients undergoing ENT surgeries. Higher risk surgical procedures were associated with higher prevalence of preoperative anxiety. In terms of anesthesia plan, 15.4% (95% CI 14.4% to 16.5%) of patients undergoing general anesthesia had preoperative anxiety. Patients undergoing neuraxial anesthesia or nerve block were more likely to experience preoperative anxiety, with an average prevalence greater than 20%. Patients undergoing local anesthesia had the lowest rate of preoperative anxiety (11.3%; 95% CI 0.0% to 23.5%). Patients without history of surgery had a slightly higher prevalence of preoperative anxiety (16.8%; 95% CI 15.4% to 18.3%) than those who had previously had surgery (14.9%; 95% CI 13.6% to 16.3%). Estimated operation time, operation sequence, and nature of disease did not significantly influence preoperative anxiety.

Multivariable logistic regression showed that younger age, female sex, non-retired people, poor sleep quality, no previous history of surgery, and high-risk surgery (CHA ≥ 2) were associated with increased risk for preoperative anxiety (Table 2).

Discussion

This study was the largest nationwide cross-sectional investigation of preoperative anxiety in China including more than 5,000 surgical patients. The results showed that the overall prevalence of preoperative anxiety in Chinese adult patients undergoing elective surgery was 15.8%. Compared with previously reported rates of 11 to 89% [3, 14, 21, 22], the prevalence of preoperative anxiety in this study was lower than those from previous domestic [21] and overseas studies.

Several factors may have contributed to the differences between this study and others. Our study aimed to determine the overall prevalence of preoperative anxiety in all surgical patients in China. Therefore, patients undergoing diverse surgical procedures were recruited. Previous studies reported a preoperative anxiety prevalence of approximately 30% in gynecology, orthopedic, or cardiac patients [8, 10, 23,24,25], approximately 20% in gastrointestinal patients [13], and approximately 10% in esthetic plastic surgery patients [14]. Although nearly one-fifth of our patients were from obstetrics and gynecology departments, where prevalence of preoperative anxiety was anticipated to be high, many patients were from other departments including general surgery, orthopedics, ENT, and urology, where patients were less likely to experience preoperative anxiety. Second, this study was a cross-sectional study conducted in a 2-month period without selection of specific surgical type or patient characteristics, and reflected the actual profile of surgeries conducted in China. Therefore, the majority were low-risk surgeries, which might have contributed to the lower prevalence of preoperative anxiety. Third, this study was conducted in tertiary referral centers and teaching hospitals. Highly regarded reputations of these hospitals might have mitigated preoperative anxiety in many patients. Moreover, preoperative education by surgical team, and increased access to surgical and anesthetic knowledge on the internet may have allowed patients in this study to better understand what they might experience during the perioperative phase.

The lower prevalence of preoperative anxiety in this study indicated that previous studies focusing on certain surgical types at single centers might have overestimated preoperative anxiety. Despite the relatively low prevalence of preoperative anxiety in this cross-sectional survey, the large number of surgical patients in China suggests that millions of patients might experience preoperative anxiety annually.

Compatibility of the anxiety assessment tools used in this study with the Chinese cultural context was crucial for preoperative anxiety evaluation. The PAS-7 is a self-report scale specifically designed for Chinese surgical patients. As Chinese patients are often reserved with regard to negative psychological feelings, but more likely to express anxiety-related physical discomfort, the PAS-7 innovatively introduced three questions about physical symptoms, allowing for inclusion of somatic anxiety in the assessment.

Potential characteristics associated with preoperative anxiety included female sex, non-retired, no previous surgery experience, and high-risk surgery, which were consistent with previous studies [26]. Male patients might feel more difficult to express their anxiety due to social and cultural pressure, which could influence the results. A previous study reported preoperative anxiety prevalence up to 60% in patients with thyroid nodules waiting for pathological diagnosis [12], but no significant differences were observed in this study among patients undergoing surgery for benign lesions, malignancies, or lesions with unknown properties. In this study, we found that younger patients were more anxious preoperatively. Many studies have shown that levels of anxiety differ with age [27]. A previous systematic review suggested that patients above 55 years old were less likely to suffer from generalized anxiety disorder [28]. Younger patients, particularly those at working age, were more vulnerable to higher levels of anxiety [29]. While younger adults are often afraid of intraoperative awareness, unsuccessful anesthesia, postoperative pain, and postoperative complications which might impact their long-term quality of life, or even shorten their lifespan [2, 27], elderly patients are less likely to express their fears regarding anesthesia and surgery.

Poor quality of sleep was associated with preoperative anxiety and may be a target to reduce preoperative anxiety. Benzodiazepines and melatonin as premedication for surgical patients have been shown in the clinical setting to reduce preoperative and postoperative anxiety, resulting in improved perioperative experience and postoperative recovery [30]. However, whether poor sleep caused preoperative anxiety requires further investigation.

This study was subject to several limitations. First, although this was largest nationwide cross-sectional study of preoperative anxiety, the participating medical centers were mainly tertiary referral hospitals that provide high-quality medical care and may not reflect the conditions in secondary or primary care facilities. We also did not include hospitals in several provinces, especially in western China, where medical resources might be scarce. Future studies should focus more on primary care facilities. Second, the cluster sampling used in this study may lead to selection bias compared to multistage probability sampling. To minimize potential bias, eligible research centers were selected during several expert panel discussions, and factors such as geographic distribution, surgical volume, and surgical specialties were considered. The relatively large sample size of this study might have mitigated representative sampling concerns. Third, since the preoperative anxiety evaluation was primarily completed in waiting areas just before anesthesia, more detailed information about potential reasons for anxiety was not evaluated. Postoperative prognosis was not collected for this study, which prevented evaluation of the association between preoperative anxiety and prognosis. Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of this study precluded determination of causality. For example, we could not ascertain whether poor quality of sleep caused anxiety or anxiety caused poor sleep. Finally, patients with mental illnesses, long-term usage of psychotropic medications, or substance use disorders were excluded to minimize outliers, as the majority of surgical patients in China have no history of mental illness and condition of substance dependence is very rare. However, individuals with mental illness or substance dependence may require special psychological assessment and intervention preoperatively. Further cohort studies should address these limitations.

In conclusion, preoperative anxiety is relatively common among adult Chinese patients undergoing elective surgeries. More attention should be paid to screening and prevention of preoperative anxiety using scenario-suitable assessment tools, and perioperative education and intervention. Further clinical studies are needed to determine appropriate approaches to preoperative anxiety assessment in China, particularly in primary hospitals.

References

Gorsky K, Black ND, Niazi A, Saripella A, Englesakis M, Leroux T et al (2021) Psychological interventions to reduce postoperative pain and opioid consumption: a narrative review of literature. Reg Anesth Pain Med 46:893–903

Mavridou P, Dimitriou V, Manataki A, Arnaoutoglou E, Papadopoulos G (2013) Patient’s anxiety and fear of anesthesia: effect of gender, age, education, and previous experience of anesthesia. A survey of 400 patients. J Anesth. 27:104–8

Eberhart L, Aust H, Schuster M, Sturm T, Gehling M, Euteneuer F et al (2020) Preoperative anxiety in adults - a cross-sectional study on specific fears and risk factors. BMC Psychiatry 20:140

Woldegerima YB, Fitwi GL, Yimer HT, Hailekiros AG (2018) Prevalence and factors associated with preoperative anxiety among elective surgical patients at University of Gondar Hospital. Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia, 2017. A cross-sectional study. Int J Surg Open 10:21–9

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (2013) DSM-5™, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Arlington, VA, US

Uysal AI, Altiparmak B, Korkmaz Toker M, Dede G, Sezgin C, Gumus DS (2020) The effect of preoperative anxiety level on mean platelet volume and propofol consumption. BMC Anesthesiol 20:34

Yilmaz Inal F, Yilmaz Camgoz Y, Daskaya H, Kocoglu H (2021) The effect of preoperative anxiety and pain sensitivity on preoperative hemodynamics, propofol consumption, and postoperative recovery and pain in endoscopic ultrasonography. Pain Ther 10:1283–1293

Ma J, Li C, Zhang W, Zhou L, Shu S, Wang S et al (2021) Preoperative anxiety predicted the incidence of postoperative delirium in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol 21:48

Oteri V, Martinelli A, Crivellaro E, Gigli F (2021) The impact of preoperative anxiety on patients undergoing brain surgery: a systematic review. Neurosurg Rev 44:3047–3057

Milisen K, Van Grootven B, Hermans W, Mouton K, Al Tmimi L, Rex S et al (2020) Is preoperative anxiety associated with postoperative delirium in older persons undergoing cardiac surgery? Secondary data analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 20:478

Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Molina G, Lipsitz SR, Esquivel MM, Uribe-Leitz T et al (2016) Size and distribution of the global volume of surgery in 2012. Bull World Health Organ 94:201–209

Yang Y, Ma H, Wang M, Wang A (2017) Assessment of anxiety levels of patients awaiting surgery for suspected thyroid cancer: a case-control study in a Chinese-Han population. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 9:e12245

Liu QR, Ji MH, Dai YC, Sun XB, Zhou CM, Qiu XD et al (2021) Predictors of acute postsurgical pain following gastrointestinal surgery: a prospective cohort study. Pain Res Manag 2021:6668152

Wei L, Ge C, Xiao W, Zhang X, Xu J (2018) Cross-sectional investigation and analysis of anxiety and depression in preoperative patients in the outpatient department of aesthetic plastic surgery in a general hospital in China. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 71:1539–1546

Wu H, Zhao X, Chu S, Xu F, Song J, Ma Z et al (2020) Validation of the Chinese version of the amsterdam preoperative anxiety and information scale (APAIS). Health Qual Life Outcomes 18:66

Zhang C, Liu X, Hu T, Zhang F, Pan L, Luo Y et al (2021) Development and psychometric validity of the perioperative anxiety scale-7 (PAS-7). BMC Psychiatry 21:358

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR (1999) Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Am J Infect Control 27:97–134

Wan RFX. (2020) [Brief analysis of the implementation of Surgical Risk Evaluation Form]. China Health Human Resources. 36–8.

Agresti A, Coull BA (1998) Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Ame Statist 52:119–126

Tulloch I, Rubin JS (2019) Assessment and Management of Preoperative Anxiety. J Voice 33:691–696

Li XR, Zhang WH, Williams JP, Li T, Yuan JH, Du Y et al (2021) A multicenter survey of perioperative anxiety in China: Pre- and postoperative associations. J Psychosom Res 147:110528

Lim S, Oh Y, Cho K, Kim MH, Moon S, Ki S (2020) The question of preoperative anxiety and depression in older patients and family protectors. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 15:217–225

Wong M, Vogell A, Wright K, Isaacson K, Loring M, Morris S (2019) Opioid use after laparoscopic hysterectomy: prescriptions, patient use, and a predictive calculator. Am J Obstet Gynecol 220(259):e1–e11

Bian T, Shao H, Zhou Y, Huang Y, Song Y (2021) Does psychological distress influence postoperative satisfaction and outcomes in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty? A prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22:647

Erkilic E, Kesimci E, Soykut C, Doger C, Gumus T, Kanbak O (2017) Factors associated with preoperative anxiety levels of Turkish surgical patients: from a single center in Ankara. Patient Prefer Adherence 11:291–296

Aust H, Eberhart L, Sturm T, Schuster M, Nestoriuc Y, Brehm F et al (2018) A cross-sectional study on preoperative anxiety in adults. J Psychosom Res 111:133–139

Balsamo M, Cataldi F, Carlucci L, Fairfield B (2018) Assessment of anxiety in older adults: a review of self-report measures. Clin Interv Aging 13:573–593

Craske MG, Stein MB (2016) Anxiety. Lancet 388:3048–3059

Inhestern L, Beierlein V, Bultmann JC, Moller B, Romer G, Koch U et al (2017) Anxiety and depression in working-age cancer survivors: a register-based study. BMC Cancer 17:347

Madsen BK, Zetner D, Moller AM, Rosenberg J (2020) Melatonin for preoperative and postoperative anxiety in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD009861

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Bin Liu, Changhong Miao, Duozhi Wu, Fuhai Ji, Hailong Dong, Hong Ma, Hui Qiao, Jianjun Yang, Jianshe Yu, Junfang Rong, Junmei Xu, Kaizhi Lu, Liangcheng Zhang, Min Yan, Shibiao Chen, Tianlong Wang, Wei Han, Weifeng Yu, Wenqi Huang, Wenzhi Li, Xiangdong Chen, Xiaoming Deng, Xiaoqing Chai, Xinli Ni, Yan Luo, Yonghao Yu, Yongyu Si, Yuelan Wang, and Zheng Guo (in alphabetical order) from each participating medical center for their substantial support conducting this study.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC2001900) and Beijing Medical Award Foundation (YXJL-2019–1309).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiawen Yu and Yuelun Zhang contributed equally to this article. YZ, TY, WM, SY, ZW, LX, and YH contributed to study conception and design. LX and YH supervised the study. JY and YZ contributed to acquisition of data. JY, YZ, and LX contributed to statistical analyses and interpretation. JY and YZ drafted the manuscript. LX and YH critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committees at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (reference number S-K 947) on November 8, 2019.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Tables

3,

4,

Appendix 2

List of participating hospitals

-

1.

Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical College (Inner Mongolia)

-

2.

Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical College (Guizhou)

-

3.

Anhui Provincial Hospital (Anhui)

-

4.

Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University (Beijing)

-

5.

Changhai Hospital affiliated to Naval Military Medical University (Shanghai)

-

6.

Chongqing Southwest Hospital (Chongqing)

-

7.

First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Jiangxi)

-

8.

First Hospital of Jilin University (Jilin)

-

9.

Fudan University Cancer Hospital (Shanghai)

-

10.

Hainan Provincial People's Hospital (Hainan)

-

11.

Hebei Provincial People's Hospital (Hebei)

-

12.

Ningxia Medical University General Hospital (Ningxia)

-

13.

Peking Union Medical College Hospital (Beijing)

-

14.

Chinese PLA General Hospital (Beijing)

-

15.

Qianfoshan Hospital of Shandong Province (Shandong)

-

16.

Renji Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Shanghai)

-

17.

Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Shanghai)

-

18.

Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (Heilongjiang)

-

19.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Military Medical University (Shaanxi)

-

20.

The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University (Liaoning)

-

21.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (Jiangsu)

-

22.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangdong)

-

23.

The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Henan)

-

24.

The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical College (Yunnan)

-

25.

The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Zhejiang)

-

26.

The Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (Shanxi)

-

27.

The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Hunan)

-

28.

Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (Tianjin)

-

29.

Union Hospital affiliated to Fujian Medical University (Fujian)

-

30.

Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Hubei)

-

31.

West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Sichuan)

-

32.

Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (Beijing)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, J., Zhang, Y., Yu, T. et al. Preoperative Anxiety in Chinese Adult Patients Undergoing Elective Surgeries: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. World J Surg 46, 2927–2938 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-022-06720-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-022-06720-9