Abstract

Summary

Linear regression was applied to data from 275 persons with osteoporosis-related fracture to estimate EQ-5D-US and SF-6D health state values from the Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire. The models explained 56% and 58% of the variance in scores, respectively, and root mean square error values (0.096 and 0.085) indicated adequate prediction for use when actual values are unavailable.

Introduction

This study was conducted to provide models that predict EQ-5D-US and SF-6D societal health state values from the Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire (OPAQ).

Methods

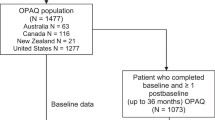

OPAQ, EQ-5D, and SF-6D data from individuals at two centers with prior osteoporosis-related fracture were used. Fractures were classified by type as hip/hip-like, spine/spine-like, or wrist/wrist-like. Spearman rank correlations between preference-based system (EQ-5D and SF-6D) dimensions and OPAQ subscales were estimated. Linear regression was used to estimate preference-based system health state values based on OPAQ subscales. We assessed models including age, sex, and fracture type and chose the model with the best performance based on the root mean square error (RMSE) estimate.

Results

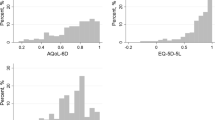

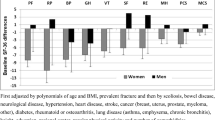

Among the 275 participants (198 women), with mean age of 68 years (range 50–94), the distribution of fracture types included 10% hip/5% hip-like, 18% spine/11% spine-like, and 24% wrist/18% wrist-like. The final regression model for EQ-5D-US included three OPAQ attributes (physical function, emotional status, and symptoms), predicted 56% of the variance in EQ-5D-US scores, and had a RMSE of 0.096. The final model for SF-6D, which included all four OPAQ dimensions, predicted 58% of the variance in SF-6D scores and had a RMSE of 0.085.

Conclusions

Two models were developed to estimate EQ-5D-US and SF-6D health state values from OPAQ and demonstrated adequate prediction for use when actual values are not available.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bloom BS (2004) Use of formal benefit/cost evaluations in health system decision making. Am J Manage Care 10(5):329–335, see comment

Gold M, Franks P, Erickson P (1996) Assessing the health of the nation. The predictive validity of a preference-based measure and self-rated health. Med Care 34(2):163–177

Randell AG, Bhalerao N, Nguyen TV, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA, Silverman SL (1998) Quality of life in osteoporosis: reliability, consistency, and validity of the Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire. J Rheumatol 25(6):1171–1179

Torrance GW (1986) Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal: a review. J Health Econ 5(4):1–30

Torrance GW, Thomas WH, Sackett DL (1972) Utility maximization model for evaluation of health care programs. Health Serv Res 7(2):118–133

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC (1996) Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford University Press, New York

Kaplan RM, Anderson JP (1988) A general health policy model: update and applications. Health Serv Res 23(2):203–235

Brooks R (1996) EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 37(1):53–72

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M (2002) The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 21(2):271–292

Torrance GW, Furlong W, Feeny D, Boyle M (1995) Multi-attribute preference functions. Health Utilities Index. Pharmacoeconomics 7(6):503–520

Fryback DG, Dasbach EJ, Klein R, Klein BEK, Dorn N, Peterson K et al (1993) The Beaver Dam Health Outcomes Study: initial catalogue of health-state quality factors. Med Decis Mak 13(2):89–102

Hollingworth W, Deyo RA, Sullivan SD, Emerson SS, Gray DT, Jarvik JG (2002) The practicality and validity of directly elicited and SF-36 derived health state preferences in patients with low back pain. Health Econ 11(1):71–85

Lee TA, Hollingworth W, Sullivan SD (2003) Comparison of directly elicited preferences to preferences derived from the SF-36 in adults with asthma. Med Decis Mak 23:323–334

Fryback DG, Lawrence WF, Martin PA, Klein R, Klein BE (1997) Predicting quality of well-being scores from the SF-36: results from the Beaver Dam Health Outcomes Study. Med Decis Mak 17(1):1–9

Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Isacson DG, Borgquist L (1999) The relationship between health-state utilities and the SF-12 in a general population. Med Decis Mak 19(2):128–140

Franks P, Lubetkin EI, Gold MR, Tancredi DJ, Jia H (2004) Mapping the SF-12 to the Euroqol EQ-5D Index in a national US sample. Med Decis Mak 24:247–254

Sengupta N, Nichol MB, Wu J, Globe D (2004) Mapping the SF-12 to the HUI3 and VAS in a managed care population. Med Care 42(9):927–937

Sanderson K, Andrews G, Corry J, Lapsley H (2004) Using the effect size to model change in preference values from descriptive health status. Qual Life Res 13(7):1255–1264

Brazier JE, Roberts J (2004) The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care 42(9):851–859

Gray AM, Rivero-Arias O, Clarke PM (2006) Estimating the association between SF-12 responses and EQ-5D utility values by response mapping. Med Decis Mak 26(1):18–29

Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V (2006) Mapping the EQ-5D Index from the SF-12: US general population preferences in a nationally representative sample. Med Decis Mak 26:401–409

Lenert LA, Sturley AP, Rapaport MH, Chavez S, Mohr PE, Rupnow M (2004) Public preferences for health states with schizophrenia and a mapping function to estimate utilities from positive and negative symptom scale scores. Schizophr Res 71(1):155–165

Kind P, Macran S (2005) Eliciting social preference weights for Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung health states. Pharmacoeconomics 23(11):1143–1153

Brazier J, Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR (2004) Estimating a preference-based single index for the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite) instrument from the SF-6D. Value Health 7(4):490–498

Buxton M, Lacey L, Feagan B, Niecko T, Miller D, Townsend R (2007) Mapping from disease-specific measures to utility: an analysis of the relationships between the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire and Crohn's Disease Activity Index in Crohn's disease and measures of utility. Value Health 10(3):214–220

Erickson P (1998) Evaluation of a population-based measure of quality of life: the Health and Activity Limitation Index (HALex). Qual Life Res 7:101–114

Gabriel SE, Tosteson AN, Leibson CL, Crowson CS, Pond GR, Hammond CS et al (2002) Direct medical costs attributable to osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 13(4):323–330

Tosteson AN, Gabriel SE, Grove MR, Moncur MM, Kneeland TS, Melton LJ 3rd et al (2001) Impact of hip and vertebral fractures on quality-adjusted life years. Osteoporos Int 12(12):1042–1049

(1998) Osteoporosis: Review of the evidence for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment and cost-effectiveness analysis. Osteoporos Int 8(Suppl 4):S1–S88

Silverman SL (2000) The Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire (OPAQ): a reliable and valid disease-targeted measure of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in osteoporosis. Qual Life Res 9(s1):767–774

Silverman SL, Mason J, Greenwald M (1993) The Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire (OPAQ): a reliable and valid self assessment measure of quality of life in osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 8(Suppl 1):s343

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30(6):473–483

Brazier J, Usherwood T, Harper R, Thomas K (1998) Deriving a preference-based single index from the UK SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 51(11):1115–1128

Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ (2005) US valuation of the EQ-5D health states. Development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care 43(3):203–220

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA (1992) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45:613–619

Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG (1993) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol 46:1075–1079

Mortimer D, Segal L (2008) Comparing the incomparable? A systematic review of competing techniques for converting descriptive measures of health status into QALY weights. Med Decis Mak 28(1):66–89

Revicki D, Kawata A, Harnam N, Chen W, Hays R, Cella D (2009) Predicting EuroQol (EQ-5D) scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items and domain item banks in a United States sample. Qual Life Res 18:783–791

Bansback N, Marra C, Tsuchiya A, Anis A, Guh D, Hammond T et al (2007) Using the Health Assessment Questionnaire to estimate preference-based single indices in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 57(6):963–971

Feeny D (2006) As good as it gets but good enough for which applications? Med Decis Mak 26:307–309

Kaplan R, Groessl EJ, Sengupta N, Sieber WJ, Ganiats TG (2005) Comparison of measured utility scores and imputed scores from the SF-36 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Med Care 43(1):79–87

Sherbourne C, Unutzer J, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Lenert L, Sturm R et al (2001) Can utility-weighted health-related quality-of-life estimates capture health effects of quality improvement for depression? Med Care 39(11):1246–1259

McDonough CM, Grove MR, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Hilibrand AS, Tosteson AN (2005) Comparison of EQ-5D, HUI, and SF-36-derived societal health state values among spine patient outcomes research trial (SPORT) participants. Qual Life Res 14(5):1321–1332

Pickard AS, Wang Z, Walton SM, Lee TA (2005) Are decisions using cost-utility analyses robust to choice of SF-36/SF-12 preference-based algorithm? Health Qual Life Outcomes 3(1):11

Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Ratcliffe J et al (2005) Longer term clinical and economic benefits of offering acupuncture care to patients with chronic low back pain. Health Technol Assess 9(32):1–109

Wee H-L, Machin D, Loke W-C, Li S-C, Cheung Y-B, Luo N et al (2007) Assessing differences in utility scores: a comparison of four widely used preference-based instruments. Value Health 10(4):256–265

Burns AW, Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, MacDonald SJ, Rorabeck CH (2006) Cost effectiveness of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 446:29–33

McDonough C, ANA T (2007) Measuring preferences for cost-utility analysis: how choice of method may influence decision-making. Pharmacoeconomics 25(2):93–106

Stiggelbout AM (2006) Health state classification systems: how comparable are our ratios? Med Decis Mak 25:223–225

Fryback DG, Palta M, Cherepanov D, Bolt D, Kim J-S (2010) Comparison of 5 health-related quality of life indexes using item response theory analysis. Med Decis Mak 30:5–15

Lima VD, Kopec JA (2005) Quantifying the effect of health status on health care utilization using a preference-based health measure. Soc Sci Med 60(3):515–524

World Health Organization (2002) Towards a common language for functioning, disability, and health ICF: the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Silverman S, Minshall ME, Shen W, Harper KD, Xie S (2001) The relationship of health-related quality of life to prevalent and incident vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Results from the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation Study. Arthritis Rheum 44(11):2611–2619

Strom O, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O, Lidgren L, Ponzer S et al (2008) Long-term cost and effect on quality of life of osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Acta Orthop 79(2):269–280

Oleksik A, Lips P, Dawson A, Minshall ME, Shen W, Cooper C et al (2000) Health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women with low BMD with or without prevalent vertebral fractures. J Bone Miner Res 15(7):1384–1392

van Schoor NM, Ewing SK, O'Neill TW, Lunt M, Smit JH, Lips P et al (2008) Impact of prevalent and incident vertebral fractures on utility: results from a patient-based and a population-based sample. Qual Life Res 17(1):159–167

Hagino H, Nakamura T, Fujiwara S, Oeki M, Okano T, Teshima R et al (2009) Sequential change in quality of life for patients with incident clinical fractures: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 20(5):695–702

Cooper C, Jakob F, Chinn C, Martin-Mola E, Fardellone P, Adami S et al (2008) Fracture incidence and changes in quality of life in women with an inadequate clinical outcome from osteoporosis therapy: the Observational Study of Severe Osteoporosis (OSSO). Osteoporos Int 19(4):493–501

Jakob F, Marin F, Martin-Mola E, Torgerson D, Fardellone P, Adami S et al (2006) Characterization of patients with an inadequate clinical outcome from osteoporosis therapy: the Observational Study of Severe Osteoporosis (OSSO). QJM 99(8):531–543

Rajzbaum G, Jakob F, Karras D, Ljunggren O, Lems WF, Langdahl BL et al (2008) Characterization of patients in the European Forsteo Observational Study (EFOS): postmenopausal women entering teriparatide treatment in a community setting. Curr Med Res Opin 24(2):377–384

Cockerill W, Lunt M, Silman AJ, Cooper C, Lips P, Bhalla AK et al (2004) Health-related quality of life and radiographic vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 15(2):113–119

van Schoor NM, Smit JH, Twisk JW, Lips P, van Schoor NM, Smit JH et al (2005) Impact of vertebral deformities, osteoarthritis, and other chronic diseases on quality of life: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 16(7):749–756

Sullivan PW, Lawrence WF, Ghushchyan V, Sullivan PW, Lawrence WF, Ghushchyan V (2005) A national catalog of preference-based scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Care 43(7):736–749

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG12262, P60-AR048094, and 1F32HD056763) and a New Investigator Fellowship Training Initiative (NIFTI) in Health Services Research Award from the Foundation for Physical Therapy.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDonough, C.M., Grove, M.R., Elledge, A.D. et al. Predicting EQ-5D-US and SF-6D societal health state values from the Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire. Osteoporos Int 23, 723–732 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1619-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1619-9