Abstract

Summary

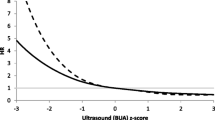

We hypothesized that combining clinical risk factors (CRF) with the heel stiffness index (SI) measured via quantitative ultrasound (QUS) would improve the detection of women both at low and high risk for hip fracture. Categorizing women by risk score improved the specificity of detection to 42.4%, versus 33.8% using CRF alone and 38.4% using the SI alone. This combined CRF-SI score could be used wherever and whenever DXA is not readily accessible.

Introduction and hypothesis

Several strategies have been proposed to identify women at high risk for osteoporosis-related fractures; we wanted to investigate whether combining clinical risk factors (CRF) and heel QUS parameters could provide a more accurate tool to identify women at both low and high risk for hip fracture than either CRF or QUS alone.

Methods

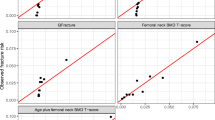

We pooled two Caucasian cohorts, EPIDOS and SEMOF, into a large database named “EPISEM”, in which 12,064 women, 70 to 100 years old, were analyzed. Amongst all the CRF available in EPISEM, we used only the ones which were statistically significant in a Cox multivariate model. Then, we constructed a risk score, by combining the QUS-derived heel stiffness index (SI) and the following seven CRF: patient age, body mass index (BMI), fracture history, fall history, diabetes history, chair-test results, and past estrogen treatment.

Results

Using the composite SI-CRF score, 42% of the women who did not report a hip fracture were found to be at low risk at baseline, and 57% of those who subsequently sustained a fracture were at high risk. Using the SI alone, corresponding percentages were 38% and 52%; using CRF alone, 34% and 53%. The number of subjects in the intermediate group was reduced from 5,400 (including 112 hip fractures) and 5,032 (including 111 hip fractures) to 4549 (including 100 including fractures) for the CRF and QUS alone versus the combination score.

Conclusions

Combining clinical risk factors to heel bone ultrasound appears to correctly identify more women at low risk for hip fracture than either the stiffness index or the CRF alone; it improves the detection of women both at low and high risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Melton LJ 3rd (1995) How many women have osteoporosis now? J Bone Miner Res 10(2):175–177

Riggs BL, Melton LJ 3rd (1986) Medical progress series: Involutional osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 314:1676–1686

Riggs BL, Melton LJ 3rd (1995) The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone 17(5 Suppl):505S–511S

Kelsey JL, Hoffman S (1987) Risk factors for hip fracture. N Engl J Med 316(7):404–406

Statistics NCfH (1986) Advance data from vital and health statistics: 1985 summary: national hospital discharge survey. US Public Health Service (PHS), Hyattsville, pp PHS 86–1250

Cummings SR, Kelsey JL, Nevitt MC et al. (1985) Epidemiology of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. Epidemiol Rev 7:178–208

Melton LJ 3rd, Riggs BL (1987) Epidemiology of age-related fractures The osteoporotic syndrome: detection, prevention, and treatment. Grune & Stratton, New York, pp 45–72

Cummings SR, Black DM, Rubin SM (1989) Lifetime risks of hip, Colles’, or vertebral fracture and coronary heart disease among white postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 149(11):2445–2448

Black DM, Cummings SR, Melton LJ, 3rd 1992 Appendicular bone mineral and a woman’s lifetime risk of hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res 7(6):639–646

Baudoin C (1997) [Fractures of the proximal femur. Epidemiology and economic impact]. Presse Med 26(3):1451–1456

Melton LJ 3rd (1996) Epidemiology of hip fractures: implications of the exponential increase with age. Bone 18(3 Suppl):121S–125S

Fisher ES, Baron JA, Malenka DJ et al (1991) Hip fracture incidence and mortality in New England. Epidemiology 2(2):116–122

Sernbo I, Johnell O (1993) Consequences of a hip fracture: a prospective study over 1 year. Osteoporosis Int 3(3):148–153

Wolinsky FD, Fitzgerald JF, Stump TE (1997) The effect of hip fracture on mortality, hospitalization, and functional status: a prospective study. Am J Public Health 87(3):398–403

Cummings SR, Rubin SM, Black D (1990) The future of hip fractures in the United States. Numbers, costs, and potential effects of postmenopausal estrogen. Clin Orthop (252):163–166

IOF 2000 How fragile is her future? IOF Report

Siris ES, Brenneman SK, Barrett-Connor E et al (2006) The effect of age and bone mineral density on the absolute, excess, and relative risk of fracture in postmenopausal women aged 50–99: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA). Osteoporos Int:1–10

Hans D, Dargent-Molina P, Schott AM et al (1996) Ultrasonographic heel measurements to predict hip fracture in elderly women: the EPIDOS prospective study. Lancet 348(9026):511–514

Bauer DC, Gluer CC, Cauley JA et al (1997) Broadband ultrasound attenuation predicts fractures strongly and independently of densitometry in older women. A prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med 157(6):629–634

Krieg MA, Comuz J, Ruffieux C et al (2004) [Role of bone ultrasound in predicting hip fracture risk in women 70 years or older: results of the SEMOF study and comparison with literature data]. Rev Med Suisse Romande 124(2):59–62

Gluer CC, Cummings SR, Bauer DC et al (1996) Osteoporosis: association of recent fractures with quantitative US findings. Radiology 199(3):725–732

Dargent-Molina P, Schott AM, Hans D et al (1999) Separate and combined value of bone mass and gait speed measurements in screening for hip fracture risk: results from the EPIDOS study. Epidemiologie de l’Osteoporose. Osteoporosis Int 9(2):188–192

Porter RW, Miller CG, Grainger D et al (1990) Prediction of hip fracture in elderly women: a prospective study. Bmj 301(6753):638–641

Garnero P, Dargent-Molina P, Hans D et al (1998) Do markers of bone resorption add to bone mineral density and ultrasonographic heel measurement for the prediction of hip fracture in elderly women? The EPIDOS prospective study. Osteoporosis Int 8(6):563–569

Schott AM, Hans D, Duboeuf F et al (2005) Quantitative ultrasound parameters as well as bone mineral density are better predictors of trochanteric than cervical hip fractures in elderly women. Results from the EPIDOS study. Bone 37(6):858–863

Dargent-Molina P, Piault S, Breart G (2003) A comparison of different screening strategies to identify elderly women at high risk of hip fracture: results from the EPIDOS prospective study. Osteoporosis Int 14(12):969–977

Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS et al (1995) Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med 332(12):767–773

De Laet CE, van Hout BA, Burger H et al (1997) Bone density and risk of hip fracture in men and women: cross sectional analysis. Bmj 315(7102):221–225

Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC Jr (1988) Age and bone mass as predictors of fracture in a prospective study. J Clin Invest 81(6):1804–1809

Lauritzen JB, Schwarz P, McNair P et al (1993) Radial and humeral fractures as predictors of subsequent hip, radial or humeral fractures in women, and their seasonal variation. Osteoporosis Int 3(3):133–137

Bonjour JP, Schurch MA, Rizzoli R (1996) Nutritional aspects of hip fractures. Bone 18(3 Suppl):139S–144S

Dawson-Hughes B (1996) Calcium insufficiency and fracture risk. Osteoporosis Int 6(Suppl 3):37–41

Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT et al (1995) Alcohol intake and bone mineral density in elderly men and women. The Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 142(5):485–492

Law MR, Hackshaw AK (1997) A meta-analysis of cigarette smoking, bone mineral density and risk of hip fracture: recognition of a major effect. Bmj 315(7112):841–846

NOF (1998) Osteoporosis review of the evidence for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment and cost-effectiveness analysis. Osteoporos Int 8(Suppl 4):S1–S88

Espallargues M, Sampietro-Colom L, Estrada MD et al (2001) Identifying bone-mass-related risk factors for fracture to guide bone densitometry measurements: a systematic review of the literature. Osteoporosis Int 12(10):811–822

Leslie WD, Metge C, Salamon EA et al (2002) Bone mineral density testing in healthy postmenopausal women. The role of clinical risk factor assessment in determining fracture risk. J Clin Densitom 5(2):117–130

Krieg MA, Cornuz J, Ruffieux C et al (2005) Non vertebral fracture risk in elderly women: a practical approach using heel bone ultrasound in association with other risk factors for osteoporosis ASBMR

Dargent-Molina P, Favier F, Grandjean H et al (1996) Fall-related factors and risk of hip fracture: the EPIDOS prospective study. Lancet 348(9021):145–149

Krieg MA, Cornuz J, Ruffieux C et al (2003) Comparison of three bone ultrasounds for the discrimination of subjects with and without osteoporotic fractures among 7562 elderly women. J Bone Miner Res 18(7):1261–1266

Njeh C, Hans D, Fuerst T et al. Calcaneal quantitative ultrasound: water-coupled. Quantitative ultrasound: assessment of osteoporosis and bone status. In: Dunitz M (ed.), London:, pp 109–124

Krieg MA, Cornuz J, Ruffieux C et al (2006) Prediction of hip fracture risk by quantitative ultrasound in more than 7000 Swiss women > or =70 years of age: comparison of three technologically different bone ultrasound devices in the SEMOF study. J Bone Miner Res 21(9):1457–1463

Durosier C, Hans D, Krieg MA et al (2006) Prediction and discrimination of osteoporotic hip fracture in postmenopausal women. J Clin Densitom 9(4):475–495

Hans D, Schott AM, Chapuy MC et al (1994) Ultrasound measurements on the os calcis in a prospective multicenter study. Calcif Tissue Int 55(2):94–99

Hans D, Hartl F, Krieg MA (2003) Device-specific weighted T-score for two quantitative ultrasounds: operational propositions for the management of osteoporosis for 65 years and older women in Switzerland. Osteoporosis Int 14(3):251–258

Gluer CC (2007) Quantitative Ultrasound-It is time to focus research efforts. Bone 40(1):9–13

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the EPIDOS and SEMOF study groups for making their databases available to us. The EPIDOS study was supported by a contract INSERM-MSD-Chibret. This analysis was partly funded by a research grant provided by Geneva University Hospital.

Members of the EPIDOS study group: Coordinators: G. Bréart, P. Dargent-Molina, P.J. Meunier, A.M. Schott, D. Hans, P.D. Delmas. Principal investigators (center): C. Baudoin, J.L. Sebert (Amiens); M.C. Chapuy, A.M. Schott (Lyon); F. Favier, C. Marcelli (Montpellier); E. Hausherr, C.J. Menkes, C. Cormier (Paris); H. Grandjean, C. Ribot (Toulouse).

Members of the SEMOF study group: M-A. Krieg, J. Cornuz, C. Ruffieux, G. Van Melle, D. Büche, M. A. Dambacher, F. Hartl, H. J Häuselmann, M. Kraenzlin, K. Lippuner, M. Neff, P. Pancaldi, R. Rizzoli, F. Tanzi, R. Theiler, A. Tyndall, C. Wimpfheimer, P. Burckhardt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Durosier, C., Hans, D., Krieg, M.A. et al. Combining clinical factors and quantitative ultrasound improves the detection of women both at low and high risk for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 18, 1651–1659 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0414-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0414-0