Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The objective of this study was to report 1 year anatomical and functional outcomes of trocar-guided total tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift™) repair for post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse with one continuous piece of polypropylene mesh.

Methods

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study of 46 patients. A minimum sample size of 35 patients was needed to detect a recurrence rate of less than 20% at 12 months. Instruments of measurement used were pelvic organ prolapse quantification and validated questionnaires.

Results

Overall anatomical success was 91% (95% confidence interval 83–99), with significant improvement in experienced bother and quality of life. Mesh exposure occurred in seven patients (15%). No adverse effects on sexual function could be detected.

Conclusions

Trocar-guided total tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift™) repair with one continuous piece of mesh for post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse is well tolerated and anatomically and functionally highly effective. Results of controlled trials will determine its position in the operative armamentarium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in women is common, affecting 50% of parous women over 50 years of age, with a lifetime prevalence risk of 30–50% [1]. A challenging aspect of POP is the treatment of the prolapsed vaginal vault. The incidence of post-hysterectomy vaginal wall prolapse that requires surgery has been estimated at 1.3 per 1,000 women-years.

The risk of prolapse surgery was 4.7 times higher in women whose initial hysterectomy was indicated by prolapse and 8.0 times higher if preoperative prolapse stage II or more was present [2].

The surgical treatment of vaginal vault prolapse can either be performed by vaginal or abdominal route. A prospective randomised clinical trial of vault prolapse, which compared the abdominal sacral colpopexy with the vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy, showed similar results in both groups with regards to subjective and objective postoperative anatomical assessment and impact on quality of life, but found that the abdominal route was associated with a longer operating time, slower return to activities of daily living, and greater cost than the vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy [3]. Both techniques have some drawbacks. Prolapse of the anterior compartment following sacrospinous colpopexy and of the posterior compartment following abdominal sacral colpopexy are well reported [4, 5]. On the other hand, treatment of the anterior and/or posterior compartment alone will invariably affect the vaginal vault [6]. The ideal solution, therefore, would be a surgical approach with minimal morbidity that simultaneously treats all three compartments with equal success.

A number of synthetic implant materials with surgical instrument kits are currently commercially available. The rationale for using these is to decrease surgical failures. One such surgical kit is designed for the total vaginal repair of vault prolapse with one continuous mesh interposition on the anterior, apical, and posterior compartment. It aims to be a bilateral sacrospinous ligament suspension as well (Prolift™, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA). The first data on the efficacy and safety of this novel transvaginal mesh technique are reported from retrospective case series and do not explicitly focus on this total vaginal mesh treatment with one continuous mesh for vault prolapse [7, 8]. Prospective data on this tension-free vaginal mesh technique were scarce and with short-term follow-up [9]. Only one paper on trocar-guided vaginal mesh repair shows a prospective follow-up of 1 year, but the authors do not discriminate between the combined anterior and posterior repair with preservation of the uterus and a true total repair with one continuous mesh for vaginal vault prolapse [10].

The aim of this paper is to exclusively report on the efficacy and safety of the total tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift™) repair with one continuous piece of mesh for the anterior, apical, and posterior compartment in case of post-hysterectomy vaginal wall prolapse.

Materials and methods

In September 2005, an ongoing prospective observational cohort study with the Prolift™ pelvic floor repair system was started in two urogynaecological centres in The Netherlands: the Reinier de Graaf Hospital in Delft and the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre.

After obtaining informed consent, consecutive patients with recurrent vaginal wall prolapse stage II or more, or with a primary vaginal wall prolapse stage III or more were enrolled in this study. Two hundred ninety-seven patients were included at the beginning of 2009. One hundred ninety-six patients (66%) had completed their 1 year follow-up. Of those, 46 patients (24%) underwent the total continuous vaginal mesh procedure for vault prolapse. Surgical procedures were performed by four surgeons who were trained prior to the start of the study. Most postmenopausal patients were treated with topical oestrogen 6–8 weeks prior to surgery and continued this treatment postoperatively when considered necessary. Concomitant anti-incontinence surgery was not performed in this patient series in order to prevent increased risk of complications as reported earlier by us [11]. All patients were counselled about this strategy prior to surgery.

Preoperatively, genital prolapse was quantified in the dorsal lithotomy position using the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) measurement system [12]. Postoperatively, POP-Q measurements were performed at both 6 and 12 months.

Surgical procedure

Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis was given with a single dose of cefalozine-natrium (Kefzol® Lilly, The Netherlands) and metronidazole (Flagyl® Aventis Pharma BV Hoevelaken, The Netherlands). Patients were positioned in the dorsal lithotomy position with their hips flexed to about 110°. The anus was covered with Tegaderm®. After liberal use of hydrodissection (lidocaine hydrochloride monohydrate 200 mg with epinephrine hydrogen tartrate 100 μg in 20 ml—Astra Zeneca BV Zoetermeer, The Netherlands—diluted in 100 ml of 0.9% saline solution), an anterior midline incision was made which included full thickness of the fibromuscular wall of the vagina from about 2.5 cm distal from the external urethral meatus to about 2 cm distal of the vaginal apex. Bilateral, mostly blunt, and incidentally sharp dissection was used to open the vesicovaginal fascia in order to reach distally the cranial side of the ischial spine, the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, and the retropubic space.

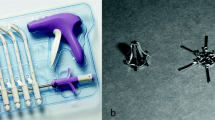

The transobturator insertion of the cannula-equipped guides, and retrieval devices have been extensively described elsewhere and were not altered in our hands [7].

After hydrodissection of the posterior vaginal wall, a full thickness vaginal wall incision was made to the vaginal apex leaving an apical bridge of vaginal tissue of about 3 cm from the anterior incision. The pararectal space was bilaterally bluntly dissected until the caudal side of the ischial spines were reached and the sacrospinous ligaments were properly identified. The cannula-equipped guides were used to perforate and pass the sacrospinous ligaments about 2 cm medially from the ischial spines as described in the paper by Fatton et al. [7]. A channel was carefully dissected under the apical bridge of the vaginal vault in order to allow passage of the posterior part of the total Prolift™ mesh. Gloves were changed to minimise colonisation of bacteria and decrease infection risk. A slender forceps was used to gently pull the posterior part of the mesh through the previously dissected channel at the level of the vault in such a manner that the middle part of the mesh exactly fitted under this bridge of vaginal tissue (Fig. 1). After fixation of the mesh with two Vicryl 00 sutures at the level of the bladder neck and two Vicryl 00 sutures close to the posterior vaginal commissure, the four anterior and two posterior mesh arms were gently pulled through the cannulas by the respective retrieval devices. The mesh was carefully spread to avoid unnecessary mesh folding, after which, the full thickness of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls were closed with a running Vicryl 00 suture, without prior vaginal wall dissection. After repositioning the vagina with two Breisky specula to its anatomical position, the cannulas were carefully withdrawn, and a finger in the rectum gently lifted the posterior mesh with the intention of preventing subsequent tension on the rectum, following possible shrinkage of the mesh. The cutaneous remnants of the mesh arms were cut, and the small skin incisions closed with rapidly dissolving Vicryl 000 suture. An iodized gauze pack was left in the vagina for at least 24 h. The indwelling urinary catheter was removed on the second postoperative day.

Study endpoints

We defined the primary endpoint of this study to be prolapse recurrence at 12 months. Anatomical failure was defined if at least one of the compartments at 12 months was classified as POP ≥stage II. Anatomical success was defined as overall POP stage 0 or I.

Secondary endpoints were anatomic success per compartment, peri- and postoperative morbidity, change in experienced bother, quality of life, and global impression of change at 6 and 12 months, as well as effects on sexual function.

Sample size

We defined study success as an upper 95% confidence interval (CI) for recurrence <20% at 12 months. We assumed that an estimated success of 90% at 12 months in the mesh-treated compartments would be realistic [8]. With this estimated 90% success rate, a two-sided 95% CI of 10% was allowed, which meant that we needed a minimum sample size of 35 patients for this study.

Data collection

To obtain data on the functional efficacy and impact on patients’ quality of life, the standard urogynaecological questionnaire of the Dutch Pelvic Floor Society was used at baseline and at 6 and 12 months, postoperatively. This questionnaire contains the validated Dutch versions of the pelvic floor distress inventory (urogenital distress inventory (UDI) and defaecatory distress inventory (DDI)), the pelvic floor impact questionnaire (incontinence impact questionnaire (IIQ)), patients global impression of improvement (PGI-I), and questions on sexual functioning [13, 14]. All data were entered into a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 16.0 database. Baseline and surgical data are presented as median (range), complications as numbers with corresponding percentages. Differences in numbers were tested using Pearson’s chi-square test.

Mean domain scores and standard deviations were calculated on the domains of UDI, DDI, and IIQ. Differences in means between baseline and postoperative scores at 6 and 12 months were tested with the paired-samples t test. A p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Forty-six consecutive patients who were operated using the total vaginal mesh procedure (Prolift™) for post-hysterectomy vaginal wall prolapse were analysed. For various reasons, we missed seven patients at the 6 months visit. At the 12 months visit, one patient refused to come for POP-Q examination, since she claimed to have no complaints. We could not convince her of the usefulness of this check-up. She was willing though to send us her completed questionnaire. One other patient was not able to complete her 12 months questionnaire because of progressive cerebral dementia, but was willing to be examined for POP-Q measurements. Median age was 66 (38–86) years. All but one patient (98%) had undergone previous prolapse surgery, of whom, four (9%), more than once. Baseline and other surgical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Anatomical results

Baseline, 6, and 12 months data per POP-Q variable, overall POP stage, and POP stage per compartment are shown in Table 2. At baseline, 40 patients (87%) were classified as having a vaginal prolapse with the leading edge at POP stage III or IV and six (13%) at stage II.

Twelve months after surgery, 41 out of 45 patients (91%: 95% CI 83–99) fulfilled the criteria of an overall anatomically successful repair. Four (9%) were thus classified as anatomical failures. One of these was classified as stage III (C + 4). She later underwent an abdominal sacral colpopexy. Mean changes from baseline per POP-Q variable at 6 and 12 months are shown in Table 2 as well. All changes are considerable and significant. The size of the genital hiatus decreased significantly with more than 1 cm, although surgery on the vaginal introitus was performed in none. The mean total vaginal length decreased by a statistically significant 0.3 cm but seemed to be not clinically significant.

Morbidity

There were no bladder or rectal perforations in this patient series as is seen in Table 1. Two patients presented postoperatively with haematoma in the buttock region, which resolved spontaneously within 10 days. A total number of seven patients (15%) were found to have a small mesh exposure, four at the 6 months follow-up and another three at the 12 months visit. Three of these mesh exposures were located on the anterior scar, two close to the level of the vault, and two in the posterior scar. All of these were asymptomatic and measured between 5 and 20 mm in size. All seven patients were initially treated with topical estrogens, and for reasons of insufficient healing, the tiny mesh exposure was excised in five patients in a day-care procedure. The two other patients preferred expectant management.

Functional results

In Table 3, data on sexual function at baseline and 12 months are shown. The percentages of patients reporting dyspareunia before and after operation were equal (37%). De novo dyspareunia occurred in two patients (18%). In another two (28%), however, dyspareunia disappeared after surgery.

Table 4 shows functional data in the domains of UDI, DDI, and IIQ as well as PGI-I [13, 14]. Scores ranged between 0 (least bother and best quality of life) to 100 (maximum bother and worst quality of life). Six and 12 months after surgery, 94% and 93% of patients, respectively, stated to be much better to very much better compared to their baseline situation.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of considerable size that prospectively and specifically evaluates the efficacy and safety of the total tension-free vaginal mesh repair using one continuous piece of polypropylene mesh for all three compartments of the prolapsed vaginal vault. The Prolift™ total prolapse repair system is unique in this respect, and at present, the only available surgical kit that offers the possibility of such a comprehensive repair. It aims at support of the weakened vaginal walls of the anterior and posterior compartments and suspension of the apical compartment by means of a bilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation thus restoring Delancey level I support [15]. Other mesh kits are designed to treat the anterior and posterior compartments, either alone or simultaneously, with a separate (split) mesh. Suspension of the vault in these procedures is not achieved by a bilateral sacrospinous ligament fixation, but by means of bilateral infracoccygeal sacropexy as described by Petros [16]. Most data on these procedures are derived from congress abstracts, retrospective reports, or studies with short follow-up [7, 9, 17]. Only a few data are published with a medium long-term follow-up, but none of these focuses exclusively on the total repair with one continuous piece of mesh [8, 10].

Anatomical effect

Considering the high percentage of patients with recurrent prolapse (98%) and high stage POP (III and IV) in this study group at baseline (87%) and the follow-up period of 1 year, the overall anatomical success of 91% is respectable. This is also reflected in the mean changes of the three most relevant POP-Q variables (Ba, C, and Bp) between baseline and 12 months, which even exceed those reported by other authors [8]. Anatomical success rates per compartment are comparable with that report.

Anatomical results in this study seem more promising than those reported by the Scandinavian group, who reported 79–82% for the anterior compartment and 81–86% for the posterior compartment [10]. Neither of these authors, however, makes a distinction between the combined anterior and posterior mesh treatment and one with a continuous piece of mesh. A clear comparison is therefore not possible. The Scandinavian group reported the combined results of 26 participating centres, while we report on only two major centres. Therefore, the number of procedures performed per surgeon and possibly the experience related to this might be different. Only one other minor study reported on 21 Prolift™ total repairs with a continuous piece of mesh and showed an anatomical success of 87% at 12 months [18]. The fairly small number of patients evaluated in that study makes 95% CI rather wide (14%) and results less comparable.

The success rate of 95% for restoration of level I support of the apex is comparable with the 74–100% success rate of apical support in abdominal sacrocolpopexy and the 89–97% success rate for restoration of apical support by sacrospinous ligament fixation [19–21]. The advantage of this total vaginal mesh procedure, however, is that it adds support to both other vaginal compartments as well, and compared to the abdominal sacrocolpopexy, has a shorter operation time and can be considered as relatively minimally invasive treatment.

At 12 months, the measured total vaginal length was a mean 0.3-cm shorter than at baseline. This slight shortening probably is due to some shrinkage of the mesh, which actually is not a shrinkage of the material itself but rather a retraction because of fibrotic reactions to the polypropylene mesh [22]. Although this slight shortening is statistically significant, we, as other authors, could not detect any clinical significance to this finding [10]. If shrinkage continues, however, this could become relevant in the future, so, longer follow-up is mandatory.

Surgical and peri-operative morbidity

In this series of patients with a total Prolift™ repair, we experienced no bladder or rectal injuries, which in the large retrospective French series are well reported in percentages of 0.7 and 0.15, respectively [23]. The rate of postoperative hematomas in our series is comparable with those of the Scandinavian and French reports [10, 23].

Mesh exposure

One important adverse effect of mesh surgery is the fairly high number of mesh exposures. We found seven (15%) after 12 months. Interestingly, we found none at the first postoperative visit at 6 weeks, but four at 6 months, and another three at the 12-month visit. Neither of these patients was symptomatic. Therefore, a very careful follow-up even beyond 12 months seems mandatory. The number of exposures in the remaining 150 patients of our database who completed their 12-month follow-up (at present data are being processed) is 10% and not statistically significant different from the percentage in this series (Pearson’s chi-square 1.067; p = 0.301). The Scandinavian group reported similar findings: the erosion percentage rose from 7% at 2 months to 11% at 12 months [10]. A similar percentage (11.3%) is also reported in the large retrospective French series [23]. Since we are not aware of the natural development of these most asymptomatic mesh erosions, we felt the urge to treat them, initially with topical estrogens, but as this was not sufficient in most cases, we performed a minor mesh excision in five (11%) patients. The remaining two patients who preferred expectant management are still symptom-free.

Of these seven patients with a tiny mesh exposure, four didn’t have intercourse at baseline, but one of these had resumed intercourse at 6 months. One other patient continued to have intercourse. Neither of both complained of dyspareunia. Of three patients in whom a mesh exposure was detected at the 12-month visit, two had intercourse at baseline. At 12 months, one of these continued to have intercourse without symptomatic dyspareunia, and the other patient had abstained from intercourse for other reasons than pain. Apparently, sexual intercourse in these patients was not hindered by the presence of these minor mesh exposures.

We found that the mean duration of surgery in the group of patients who developed a mesh exposure (92 ± 13) was 14 min longer than in those who did not (78 ± 15). Whether this is a significant item in this relatively small group of patients remains unclear. This study, however, represents a fairly complex group of patients with recurrent prolapse in all but one case. The special technique which leaves a small bridge of vaginal vault intact may jeopardise the vascularisation of the vaginal tissue and could be responsible for poor wound healing and, thus, mesh exposure. In our opinion, the rate of mesh exposures is still too high, and determinants other than those already published need to be discovered to lower this incidence [23–25].

Functional effects

Some earlier studies warned of the use of synthetic mesh in prolapse surgery because of a high risk of dyspareunia [26]. Other authors, who used modern kits with low-weight polypropylene designed by other companies, such as coated polypropylene (Ugytex, Sofradim, France) or the Perigee transobturator prolapse repair system (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN, USA), reported de novo dyspareunia after 1 year in 13% and 9% of patients, respectively [27, 28]. We detected de novo dyspareunia in two out of eleven patients (18%), but these are small numbers. On the other hand, the percentages of patients having intercourse or dyspareunia at baseline and 12 months were practically identical. In two out of seven patients (28%) who suffered from dyspareunia at baseline, this complaint was no longer present at 12 months. Furthermore, three out of 23 patients (13%) who were not having intercourse at baseline had resumed this at 12 months. These data show that prolapse itself is a cause of dyspareunia and prolapse repair, in this case, with a fairly large synthetic mesh, is able to resolve this problem in some cases. These results are comparable with observations done by the Scandinavian group, who used the short form of the pelvic organ prolapse/urinary incontinence sexual function questionnaire [29]. They observed an overall deterioration of sexual function scores in women 1 year after trocar-guided transvaginal mesh surgery. However, the worsening was attributed to decreased scores on behavioural-emotive and partner-related items, such as partner inability to obtain erection. Dyspareunia neither improved, nor worsened, as is our observation [30]. Although the rate of de novo dyspareunia seems low with the present light-weight meshes, we should remain cautious and await longer-term follow-up for realistic interpretations.

From a patients’ point of view, a subjective improvement in experienced bother and quality of life is probably more important than the objective anatomical success. This is clearly shown by the stable percentage of patients (93%) that experienced their situation to be much better to very much better, 12 months after surgery than at baseline. The improvements in the various domains of UDI, DDI, and IIQ remain stable between 6 and 12 months and are highly significant compared to baseline, except for the domains of incontinence of the UDI and constipation, pain and incontinence of the DDI, and embarrassment of the IIQ. As mentioned before, so far, it has been our strategy not to treat patients simultaneously for their prolapse and potentially manifest or masked stress urinary incontinence. All patients were counselled about this strategy before surgery. Only one patient needed and underwent a mid-urethral sling procedure between her 6- and 12-month visits because of unmasked stress urinary incontinence.

In our opinion, the strengths of this study are its prospective nature and the use of internationally accepted instruments of measurement such as validated questionnaires and POP-Q, the follow-up period of 1 year, as well as the high follow-up rate and data acquisition in all patients. A limitation of this study on the other hand is that not all POP-Q measurements were performed by an independent examiner.

Conclusion

The trocar-guided total tension-free vaginal mesh repair for post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse with one continuous piece of polypropylene mesh is very well tolerated and both anatomically and functionally highly effective at 6 and 12 months follow-up. Whether this procedure is more effective and safe than other forms of prolapse surgery remains to be determined in randomised controlled trials.

Abbreviations

- POP-Q:

-

pelvic organ prolapse quantification

- UDI:

-

urogenital distress inventory

- DDI:

-

defaecatory distress inventory

- IIQ:

-

incontinence impact questionnaire

- PGI-I:

-

patients global impression of improvement

- POP:

-

pelvic organ prolapse

References

Subak LL, Waetjen LE, van den Eeden S, Thom DH, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS (2001) Cost of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 98:646–651

Dallenbach P, Kaelin-Gambirasio I, Dubuisson JB, Boulvain M (2007) Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse repair after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 110:625–632

Maher CF, Qatawneh AM, Dwyer PL, Carey MP, Cornish A, Schluter PJ (2004) Abdominal sacral colpopexy or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 190:20–26

Aigmueller T, Riss P, Dungl A, Bauer H (2008) Long-term follow-up after vaginal sacrospinous fixation: patient satisfaction, anatomical results and quality of life. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 19:965–969

Baessler K, Schuessler B (2001) Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and anatomy and function of the posterior compartment. Obstet Gynecol 97:678–684

Cutner AS, Elneil S (2004) The vaginal vault. BJOG 111(Suppl 1):79–83

Fatton B, Amblard J, Debodinance P, Cosson M, Jacquetin B (2007) Transvaginal repair of genital prolapse: preliminary results of a new tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift technique) a case series multicentric study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 18:743–752

van Raalte HM, Lucente VR, Molden SM, Haff R, Murphy M (2008) One-year anatomic and quality-of-life outcomes after the Prolift procedure for treatment of posthysterectomy prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol . doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.058

Altman D, Vayrynen T, Engh ME, Axelsen S, Falconer C, Nordic Transvaginal Mesh Group (2008) Short-term outcome after transvaginal mesh repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 19(6):787–793

Elmer C, Altman D, Engh ME, Axelsen S, Vayrynen T, Falconer C (2009) Trocar-guided transvaginal mesh repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 113:117–126

Withagen MI, Milani AL (2007) Which factors influenced the result of a tension free vaginal tape operation in a single teaching hospital? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 86:1136–1139

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P et al (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175:10–17

van der Vaart CH, de Leeuw JR, Roovers JP, Heintz AP (2003) Measuring health-related quality of life in women with urogenital dysfunction: the urogenital distress inventory and incontinence impact questionnaire revisited. Neurourol Urodyn 22:97–104

Yalcin I, Bump RC (2003) Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:98–101

DeLancey JO (1992) Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 166:1717–1724

Petros PE (2001) Vault prolapse II: restoration of dynamic vaginal supports by infracoccygeal sacropexy, an axial day-case vaginal procedure. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 12:296–303

Abdel-Fattah M, Ramsay I (2008) Retrospective multicentre study of the new minimally invasive mesh repair devices for pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG 115:22–30

Rechberger T, Futyma K, Bartuzi A (2008) Total Prolift system surgery for treatment posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse—do we treat both anatomy and function? Ginekol Pol 79:835–839

Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, Connolly A, Cundiff G, Weber AM et al (2004) Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol 104:805–823

Claerhout F, De Ridder D, Roovers JP, Rommens H, Spelzini F, Vandenbroucke V et al (2008) Medium-term anatomic and functional results of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy beyond the learning curve. Eur Urol . doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.12.008

Morgan DM, Rogers MA, Huebner M, Wei JT, Delancey JO (2007) Heterogeneity in anatomic outcome of sacrospinous ligament fixation for prolapse: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 109:1424–1433

Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Muller M, Ottinger AP, Schumpelick V (1998) Shrinking of polypropylene mesh in vivo: an experimental study in dogs. Eur J Surg 164:965–969

Caquant F, Collinet P, Debodinance P, Berrocal J, Garbin O, Rosenthal C et al (2008) Safety of trans vaginal mesh procedure: retrospective study of 684 patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 34:449–456

Dwyer PL, O’Reilly BA (2004) Transvaginal repair of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse with Atrium polypropylene mesh. BJOG 111:831–836

Collinet P, Belot F, Debodinance P, Ha Duc E, Lucot JP, Cosson M (2006) Transvaginal mesh technique for pelvic organ prolapse repair: mesh exposure management and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 17:315–320

Milani R, Salvatore S, Soligo M, Pifarotti P, Meschia M, Cortese M (2005) Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG 112:107–111

de Tayrac R, Devoldere G, Renaudie J, Villard P, Guilbaud O, Eglin G (2007) Prolapse repair by vaginal route using a new protected low-weight polypropylene mesh: 1-year functional and anatomical outcome in a prospective multicentre study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 18:251–256

Nguyen JN, Burchette RJ (2008) Outcome after anterior vaginal prolapse repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 111:891–898

Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, Khalsa S, Qualls C (2003) A short form of the pelvic organ prolapse/urinary incontinence sexual questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 14:164–168

Altman D, Elmer C, Kiilholma P, Kinne I, Tegerstedt G, Falconer C (2009) Sexual dysfunction after trocar-guided transvaginal mesh repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 113:127–133

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Ruud van de Voorde for the medical photography and Mr. George Bazan for the image manipulation.

Conflicts of interest

A. M. occasionally performs sponsored educational activities for Gynecare Benelux. M. W. and M. V. received an educational grant and are occasionally involved in educational activities for Gynecare Benelux. This study, however, was entirely instigated by the responsible researchers and funded by university-administered research funds. Gynecare was not involved in the study set-up, study design, data collection, or whatsoever.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Milani, A.L., Withagen, M.I.J. & Vierhout, M.E. Trocar-guided total tension-free vaginal mesh repair of post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 20, 1203–1211 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0924-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0924-8