Abstract

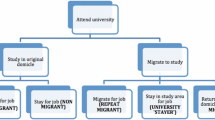

College graduates are considerably more mobile than non-graduates, and previous literature suggests that the difference is at least partially attributable to college graduates being more responsive to employment opportunities in other areas. However, there exist considerable differences in migration rates by college major that have gone largely unexplained. This paper uses microdata from the American Community Survey to examine how the migration decisions of young college graduates are affected by earnings in their college major. Results indicate that higher major-specific earnings in an individual’s state of birth reduce out-migration suggesting that college graduates are attracted toward areas that especially reward the specific type of human capital that they possess.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This paper follows most of the previous literature and uses the term “college graduates” to refer to persons whose highest completed education is a bachelor’s degree or higher.

For example, Moretti (2004) suggests that the share of the local population with a college degree creates positive human capital externalities by increasing wages for both college graduates and non-graduates in the same area. Similarly, Winters (2013) finds that a more educated local population increases labor force participation and employment probabilities for both college graduates and non-graduates.

This framework often makes several simplifying assumptions. For example, the discussion herein largely ignores complexities related to informational uncertainty, risk aversion, dual-earner households, financing constraints, etc.

For example, recent studies include Faggian et al. (2006, 2007), Waldorf (2009), Busch and Weigert (2010), Corcoran et al. (2010), Dahl and Sorenson (2010), Scott (2010), Brown and Scott (2012), Haapanen and Tervo (2012), Winters (2012), Böckerman and Haapanen (2013), Di Cintio and Grassi (2013), Faggian et al. (2013), Marinelli (2013), Knapp et al. (2013), Carree and Kronenberg (2014), Liu and Shen (2014), Nifo and Vecchion (2014), Tano (2014), Winters (2014), Abreu et al. (2015), Betz et al. (2015), and Leguizamon and Hammond (2015).

The ACS also asked individuals to report their location one year prior to the survey, which can be used to measure 1-year migration. However, 1-year migration is moderately noisy for many purposes and may be driven by short-run migration decisions. Lifetime migration should depend on long run factors.

In particular, birth-state fixed effects in Eq. (1) control for statewide differences in aggregate earnings, cost of living, and amenities. Of course, there are likely some differences in these across areas within states, but the implicit assumption is that cost of living and amenities are conditionally uncorrelated with major-specific earnings.

The mean residuals are computed by state of residence for workers in each state and college major and then merged to individuals based on their birth state. This measures the earnings of workers currently residing in one’s birth state and not the mean earnings of workers born in one’s birth state. It measures the earnings differential one might expect if they resided in their birth state. Notice also that birth-state fixed effects in Eq. (1) remove statewide differences across birth states in cost of living and amenities. Of course, there may be differences in these across areas within states

Result for the demographic characteristics are reported in “Appendix” Table 6. Results for birth state, year, and college major fixed effects are not reported to conserve space but are available from the author by request.

Table 3 Effects of major-specific earnings in birth state on birth-state out-migration, ages 22–30 Such a policy would also be costly because of a general inability to distinguish graduates making marginal location decisions from those who are infra-marginal. Thus, only a small percentage of subsidy recipients would alter their location decisions because of the subsidy.

The IV coefficient was \(-\)0.086 for men and \(-\)0.205 for women, possibly suggesting a greater responsiveness for women, but the imprecision of the estimates prevents making inferences.

Another approach considered to address measurement error was to use the broad major categories in order to increase sample sizes for which earnings are measured. Doing so yielded moderately larger OLS coefficients and similar IV coefficients as the results using detailed majors, consistent with expectations. However, the heterogeneity in majors within many broad categories makes this approach less desirable than using detailed majors.

Groups are defined to be mutually exclusive based on primary race and excluding Hispanics from other groups. Also, recall that the sample includes only persons born in the US.

Table 5 Effects of major-specific earnings on out-migration by race/ethnicity, ages 22–30 This is especially problematic for small majors, which often have zero observations for various flows and even among the “origin” population of some majors in given states. Having large numbers of zeros complicates analyses that take logarithmic transformations of migration flows. Having missing and/or noisy origin populations complicates analysis based on in-migration and net migration rates. Given the difficulties with examining in-migration, the current study maintains a focus on birth-state out-migration for simplicity.

In results not shown, I also explored using 1-year state out-migration as a binary dependent variable. Regressing a dummy for leaving the state of residence 1 year prior on major-specific regression-adjusted mean log earnings in the state 1-year prior yields a small negative coefficient that is not statistically significant at conventional levels. Unfortunately, 1-year migration is a noisy measure for the current analysis because relatively few people move across states in a given year. Furthermore, individual locations in the prior year are likely not independent of recent earnings in the state. For example, recent graduates may have already left areas paying especially low salaries to persons with their major.

References

Abel JR, Deitz R (2015) Agglomeration and job matching among college graduates. Reg Sci Urban Econ 51:14–24

Abreu M, Faggian A, McCann P (2015) Migration and inter-industry mobility of UK graduates. J Econ Geogr 15(2):353–385

Adamson DW, Clark DE, Partridge MD (2004) Do urban agglomeration effects and household amenities have a skill bias? J Reg Sci 44(2):201–224

Arcidiacono P (2004) Ability sorting and the returns to college major. J Econ 121(1):343–375

Arntz M, Gregory T, Lehmer F (2014) Can regional employment disparities explain the allocation of human capital across space? Reg Stud 48(10):1719–1738

Becker GS (1962) Investment in human capital: a theoretical analysis. J Polit Econ 70(5):9–49

Betz MR, Partridge MD, Fallah B (2015) Smart cities and attracting knowledge workers: which cities attract highly-educated workers in the 21st century? Pap Reg Sci. doi:10.1111/pirs.12163

Böckerman P, Haapanen M (2013) The effect of polytechnic reform on migration. J Popul Econ 26(2):593–617

Brown WM, Scott DM (2012) Human capital location choice: accounting for amenities and thick labor markets. J Reg Sci 52(5):787–808

Busch O, Weigert B (2010) Where have all the graduates gone? Internal cross-state migration of graduates in Germany 1984–2004. Ann Reg Sci 44(3):559–572

Carree M, Kronenberg K (2014) Locational choices and the costs of distance: empirical evidence for Dutch graduates. Spat Econ Anal 9(4):420–435

Chen Y, Rosenthal SS (2008) Local amenities and life-cycle migration: do people move for jobs or fun? J Urban Econ 64:519–537

Cooke TJ, Boyle P, Couch K, Feijten P (2009) A longitudinal analysis of family migration and the gender gap in earnings in the United States and Great Britain. Demography 46(1):147–167

Corcoran J, Faggian A, McCann P (2010) Human capital in remote and rural Australia: the role of graduate migration. Growth Change 41(2):192–210

Cunningham C, Patton MC, Reed RR (2013) Heterogeneous returns to knowledge exchange: evidence from the urban wage premium. Working paper

Dahl MS, Sorenson O (2010) The migration of technical workers. J Urban Econ 67(1):33–45

Di Cintio M, Grassi E (2013) Internal migration and wages of Italian university graduates. Pap Reg Sci 92(1):119–140

Docquier F, Marfouk A, Salomone S, Sekkat K (2012) Are skilled women more migratory than skilled men? World Dev 40(2):251–265

Faggian A, Corcoran J, McCann P (2013) Modelling geographical graduate job search using circular statistics. Pap Reg Sci 92(2):329–343

Faggian A, McCann P, Sheppard S (2006) An analysis of ethnic differences in UK graduate migration behaviour. Ann Reg Sci 40(2):461–471

Faggian A, McCann P, Sheppard S (2007) Some evidence that women are more mobile than men: gender differences in UK graduate migration behavior. J Reg Sci 47(3):517–539

Greenwood MJ (1975) Research on internal migration in the United States: a survey. J Econ Lit 13(2):397–433

Haapanen M, Tervo H (2012) Migration of the highly educated: evidence from residence spells of university graduates. J Reg Sci 52(4):587–605

Hickman DC (2009) The effects of higher education policy on the location decision of individuals: evidence from Florida’s Bright Futures Scholarship program. Reg Sci Urban Econ 39(5):553–562

Kennan J, Walker JR (2011) The effect of expected income on individual migration decisions. Econometrica 79(1):211–251

Knapp TA, White NE, Wolaver AM (2013) The returns to migration: the influence of education and migration type. Growth Change 44(4):589–607

Ladinsky J (1967) The geographic mobility of professional and technical manpower. J Hum Resour 2(4):475–494

Leguizamon JS, Hammond GW (2015) Merit-based college tuition assistance and the conditional probability of in-state work. Pap Reg Sci 94(1):197–218

Liu Y, Shen J (2014) Spatial patterns and determinants of skilled internal migration in China, 2000–2005. Pap Reg Sci 93(4):749–771

Long MC, Goldhaber D, Huntington-Klein N (2015) Do completed college majors respond to changes in wages? Econ Educ Rev 49:1–14

Malamud O, Wozniak AK (2012) The impact of college on migration: evidence from the Vietnam generation. J Hum Resour 47(4):913–950

Marinelli E (2013) Sub-national graduate mobility and knowledge flows: an exploratory analysis of onward-and return-migrants in Italy. Reg Stud 47(10):1618–1633

Moretti E (2004) Estimating the social return to higher education: evidence from longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional data. J Econ 121:175–212

Nifo A, Vecchion G (2014) Do institutions play a role in skilled migration? The case of Italy. Reg Stud 48(10):1628–1649

Partridge MD (2010) The duelling models: NEG versus amenity migration in explaining US engines of growth. Pap Reg Sci 89(3):513–536

Partridge MD, Rickman DS, Olfert MR, Ali K (2012) Dwindling U.S. internal migration: evidence of spatial equilibrium or structural shifts in local labor markets? Reg Sci Urban Econ 42(1):375–388

Rappaport J (2007) Moving to nice weather. Reg Sci Urban Econ 37(3):375–398

Rickman DS, Rickman SD (2011) Population growth in high-amenity nonmetropolitan areas: what’s the prognosis? J Reg Sci 51(5):863–879

Ruggles Steven J, Alexander T, Genadek K, Goeken R, Schroeder Matthew B, Sobek M (2010) Integrated public use microdata series: version 5.0 [machine-readable database]. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

Schwartz A (1976) Migration, age, and education. J Polit Econ 84(4):701–719

Scott AJ (2010) Jobs or amenities? Destination choices of migrant engineers in the USA. Pap Reg Sci 89(1):43–63

Sjaastad LA (1962) The costs and returns of human migration. J Polit Econ 70(5):80–93

Sjoquist DL, Winters JV (2014) Merit aid and post-college retention in the state. J Urban Econ 80:39–50

Tano S (2014) Regional clustering of human capital: school grades and migration of university graduates. Ann Reg Sci 52(2):561–581

Treyz GI, Rickman DS, Hunt GL, Greenwood MJ (1993) The dynamics of US internal migration. Rev Econ Stat 75(2):209–214

Waldorf BS (2009) Is human capital accumulation a self-propelling process? Comparing educational attainment levels of movers and stayers. Ann Reg Sci 43:323–344

Whisler RL, Waldorf BS, Mulligan GF, Plane DA (2008) Quality of life and the migration of the college-educated: a life-course approach. Growth Change 39:58–94

Winters JV (2012) Differences in employment outcomes for college town stayers and leavers. IZA J Migr 1(11):1–17

Winters JV (2013) Human capital externalities and employment differences across metropolitan areas of the USA. J Econ Geogr 13(5):799–822

Winters JV (2014) The production and stock of college graduates for US states. IZA DP No. 8730

Winters JV, Xu W (2014) Geographic differences in the earnings of economics majors. J Econ Educ 45(3):262–276

Wozniak A (2010) Are college graduates more responsive to distant labor market opportunities? J Hum Resour 45(4):944–970

Zheng L (2015) What city amenities matter in attracting smart people? Pap Reg Sci. doi:10.1111/pirs.12131