Abstract

Purpose

Distal femoral osteotomy (DFO) is a well-accepted procedure for the treatment of femoral deformities and associated symptoms including osteoarthritis, especially in younger and physically active patients in whom knee arthroplasty is undesirable. Still, there is an apparent need for evidence on relevant patient outcomes, including return to sport (RTS) and work (RTW), to further justify the use of knee osteotomy instead of surgical alternatives. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the extent and timing of patients’ RTS and RTW after DFO.

Methods

This monocentre, retrospective cohort study included consecutive DFO patients, operated between 2012 and 2015. Out of 126 eligible patients (18–70 years, 63% female), all patients responded, and 100 patients completed the questionnaire. Median follow-up was 3.4 years (range 1.5–5.2). The predominant indication for surgery was symptomatic unicompartmental osteoarthritis and valgus or varus leg alignment caused by a femoral deformity. The primary outcome measure was the percentage of RTS and RTW. Secondary outcome measures included time to RTS/RTW, sports level and frequency, the median pre-symptomatic and postoperative Tegner activity score (1–10, higher is more active) and the postoperative Lysholm score (0–100, higher is better).

Results

Out of 84 patients participating in sports preoperatively, 65 patients (77%) returned to sport postoperatively. Forty-six patients (71%) returned to sports within 6 months. Postoperative participation in high-impact sports was possible though less frequent compared to preoperative participation. Out of 80 patients working preoperatively, 73 (91%) returned to work postoperatively, of whom 59 patients (77%) returned within 6 months. The median pre-symptomatic Tegner activity score [4.0 (range 0–10)] was significantly higher (p < 0.01) than the reported Tegner score at follow-up [3.0 (range 0–10)]. The mean Lysholm score at follow-up was 68 (± 22). No significant differences were found between the osteoarthritis- and non-osteoarthritis group.

Conclusion

Eight out of ten patients return to sport and nine out of ten patients return to work after DFO. These are clinically relevant findings, because they further justify DFO as a surgical alternative to KA in young, active knee OA patients who wish to return to high activity levels.

Level of evidence

Retrospective cohort study, Level III.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is increasingly observed in active patients who are still of working age [20]. This population represents a challenge, because knee replacement is undesirable, given the three- to fivefold increased risk of revision surgery in young and active patients, compared to patients above the age of 55–65 [26]. Furthermore, meeting younger patients’ expectations is difficult, because their expectations tend to be higher than what a knee arthroplasty (KA) can deliver [1, 24]. Therefore, knee osteotomy has regained interest from surgeons who are looking for joint preserving alternatives to KA, resulting in a considerable increase in knee osteotomy surgery in the last decade [11, 28]. In cases of early-stage unicompartmental knee OA with a femoral deformity, distal femoral osteotomy (DFO) is considered the preferred treatment [10]. DFO is also a well-accepted procedure for the treatment of symptomatic unicompartmental overload and congenital malformations, especially in younger and physically active patients [6, 10, 13, 14, 35].

Yet, there is an apparent need for robust evidence on relevant patient outcomes, including return to sport (RTS) and return to work (RTW), to further justify the use of knee osteotomy instead of surgical alternatives [6, 33]. Systematic reviews on RTS and RTW after knee osteotomy showed that up to 85% of patients can RTS and RTW after high tibial osteotomy (HTO) [5, 16]. However, data on RTS and RTW after DFO are sparse. One study on varising DFO for lateral compartment OA, found that 23 of 26 patients returned to work, and 14 of 15 patients returned to their preoperative sports activities [4]. Another study, including 13 young athletes treated with varising DFO for symptomatic lateral compartment overload, found that all patients returned to sport at 2 years follow-up [31]. However, both studies described a small number of patients selected based on strict inclusion criteria, thus limiting generalizability. Furthermore, no studies on RTS and RTW have been performed in patients with DFOs other than varus-producing osteotomies. Finally, timing of return to sport and work after DFO has not been described previously. Both the extent and timing of RTS and RTW represent valuable information to the patient and the orthopaedic surgeon, that could be used to guide preoperative patient counselling, shared decision making and expectation management [2].

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the extent and timing of patients’ return to sport and work after DFO in a large cohort with different indications for distal femoral corrections. This is clinically relevant information, that may be used when counselling young, active patients to discuss their expectations regarding postoperative sport and work ability after DFO. If a return to sports and work is indeed possible after DFO, this would further justify the use of DFOs in this population. Our hypothesis was that most patients return to sport and work, including high-impact activities, after DFO.

Materials and methods

A monocentre cross-sectional study was performed in consecutive DFO patients operated on between 2012 and 2015. Eligible patients were between 18 and 70 years of age at follow-up. Patients had to understand the Dutch language and were required to be mentally able to complete the questionnaire. Patients who were treated with DFO bilaterally were asked to complete the questionnaire for the most recent operation. Eligible patients received a questionnaire by postal mail, followed by a maximum of two telephone reminders.

Patient characteristics

Patients’ age, BMI (kg/m2) and education level were asked. In addition, patients were asked if they had experienced postoperative complications and whether they had been operated on the same leg again following DFO (e.g., revision surgery or knee arthroplasty). The ASA classification, degree of correction and additional information on possible revision surgery and hardware removal were collected from the electronic medical record.

Participants

Out of 143 consecutive DFOs, 126 were eligible for inclusion and these patients were sent a questionnaire. All patients responded and 100 patients completed the questionnaire at a median follow-up of 3.5 years (range 1.4–5.2). One additional patient was excluded after completing the questionnaire, because she suffered from achondroplasia and had never worked or performed sports in her life. Figure 1 presents the in- and exclusion flow chart for this study. The predominant indication for surgery was symptomatic unicompartmental osteoarthritis. In addition, patients with a valgus or varus leg alignment caused by a femoral deformity without the presence of OA and patients with symptomatic rotational deformities of the femur were included. Finally, patients with a flexion contracture were treated with an extending DFO. Out of a total of 99 patients, 29 patients with a multiplane deformity or a concomitant tibial deformity were treated with combined osteotomies of the femur and tibia.

Surgical technique and rehabilitation

Surgery was performed by one of three dedicated knee osteotomy surgeons with 5–15 years of experience with DFO. The DFO frontal plane and transverse plane techniques have been described in previous publications [13, 14], and all techniques including the sagittal plane technique are illustrated in Fig. 2. For valgus malalignment, patients underwent a biplanar medial closing wedge osteotomy or a biplanar lateral opening wedge osteotomy. For varus malalignment, patients underwent a biplanar lateral closing wedge osteotomy. In case of additional valgus or varus malalignment of the tibia, a combined DFO and HTO were performed. Patients with rotational malalignment of the femur were treated with a single plane, de-rotation transverse DFO. Patients with an additional rotational malalignment of the tibia were also treated with a de-rotation transverse proximal tibial osteotomy. Finally, in case of a flexion contracture, patients were treated with a single plane extension DFO. Prior to surgery, a detailed planning was performed for each patient. Degrees of correction in frontal and sagittal plane were converted to millimetres of wedge to be resected, as measured on the calibrated radiographs. In the OR, callipers and rulers were used to define the wedge in the bone with K-wires under fluoroscopic guidance. Transverse plane corrections were calculated from standardized CT-scans. Intra-operatively, a tracker specifically designed for rotational measurements is used, together with K-wires defining the angle of rotation in the bone or to measure the angle of correction. Plate fixation in all patients was performed with angle stable plates (TomoFix, Synthes GmbH, Solothurn, Switzerland). Postoperatively, physiotherapy guided immediate range of motion exercises and muscle strengthening was started and all patients were restricted to partial weight bearing for 6 weeks. Thromboembolic prophylaxis, i.e., Enoxaparin 40 mg, was prescribed once daily for 6 weeks. After 6 weeks, knee radiographs were obtained to verify the degree of correction and to check for hardware complications. Progressive weight bearing was allowed thereafter, up to full weight bearing at 3 months. At 3 months postoperative, knee radiographs and full-length standing radiographs were obtained to verify bone healing and the correction of deformity.

Posteoperative anteroposterior/lateral radiographs of distal femoral osteotomies (DFOs) with projected osteotomy cuts (striped lines). a Right knee after medial closing wedge DFO, b Left knee after lateral closing wedge DFO, c Right knee after de-rotation DFO, d Left knee after anterior closing wedge DFO

Sport outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the percentage of patients that returned to sport postoperatively. Secondary outcome measures included the timing of RTS, the frequency, duration and type of performed sport activities pre- and postoperatively. No validated questionnaire exists to assess RTS in knee osteotomy patients. Therefore, a questionnaire was developed, based on the sports questionnaire described by Naal et al. in 2007, to investigate RTS after hip resurfacing arthroplasty and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) [22, 23]. This questionnaire has been used in several other studies investigating RTS after knee surgery, including studies in knee osteotomy patients [8, 25]. The questionnaire ascertains patients’ preoperative and postoperative engagement in 20 sports, e.g., cycling, jogging, golf and tennis. For the present study, 14 sports were added to the questionnaire (Supplementary material 1). Preoperative sports participation was defined as both pre-symptomatically, i.e., before the onset of restricting knee symptoms, and 1 year preoperatively. Postoperative sports participation was defined as 1 year postoperatively and at final follow-up. For each selected sport, patients reported at which of those four timepoints they had participated in that sport. For each timepoint, the highest level of participation (recreative, competitive or professional) was asked. Next, sports frequency (0–7 times per week), duration (hours per week) and timing of RTS (weeks) were asked. To assess the level of impact, sports activities were rated as low-, intermediate- or high-impact according to the classification by Vail et al. [29]. In addition, patients were asked to rate their sports ability at follow-up, compared to the best sports ability in their lifetime with the following five answering categories: much worse; worse; unchanged; improved; much improved. Finally, the Tegner activity score and the Lysholm score, which have been recently validated in Dutch [7], were collected. Patient was asked to report their pre-symptomatic Tegner score and their Tegner score at follow-up. The Lysholm score was only completed for the situation at follow-up [3].

Work outcome measures

The primary work outcome measure was the percentage of patients that returned to work postoperatively. The secondary outcome measure was the timing of RTW. First, patients were asked if they worked before the onset of restricting knee symptoms, and within 3 months preoperatively. Job title was recorded and classified as light, medium or heavy by two occupational experts, who independently scored all jobs based on work-related physical demands on the knee [19, 30]. The hours per week that patients worked 3 months preoperatively, 1 year postoperatively and at follow-up were also asked. In addition, time to RTW and changes in work load (lower; unchanged; higher) were asked. If patients did not RTW, reasons for no RTW were asked. Finally, the validated WORQ questionnaire was used to assess the impact of DFO on work-related activities [9, 18]. The WORQ consists of 13 knee-burdensome activities (e.g., kneeling, lifting/carrying, climbing stairs). Patients grade the difficulty they experience when performing each activity on a five-point Likert scale, with 0 meaning no difficulty and 4 meaning extreme difficulty/unable to perform. Patients were asked to retrospectively grade the difficulty at three timepoints: 3 months preoperatively, 1 year postoperatively and at final follow-up.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the local medical ethical review board (Academic Medical Center Amsterdam, reference number W17_382 #17.448) prior to initiation of this study. All patients provided written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data, pre- and postoperative sport participation and work status were analysed using descriptive statistics. In addition, timing of RTS and RTW, and frequency and duration of sports participation were analysed with descriptive statistics. RTS was calculated by selecting all patients that participated in one or more sports preoperatively and calculating which percentage of these patients could RTS 1 year postoperatively and/or at final FU. The unpaired T test was used to compare pre-symptomatic and postoperative Tegner scores. The WORQ scores at three timepoints were dichotomized to determine how many patients experienced severe difficulty with a work-related knee-demanding activity. “Severe difficulty” and “extreme difficulty/unable to perform” were classified as “severe difficulty”. “Moderate difficulty,” “mild difficulty” and “no difficulty” were classified as “no severe difficulty”. In addition to the primary analyses for the total group, subgroup analyses for RTS and RTW were performed for the OA patients and the non-OA patients using the Chi-square test. A p value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows (Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the total group, and of the OA- and non-OA subgroups. No intra-operative complications were encountered. There were four postoperative complications that required revision surgery: one case of a broken plate, one case of a broken and protruding screw, one case of delayed union and one case of non-union. Table 2 presents the operation type and degree of correction for the included patients.

Return to sport

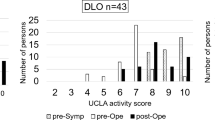

Out of 84 patients participating in one or more sports preoperatively, 65 patients (77%) returned to sport postoperatively. Time to RTS was ≤ 6 months in 71% of patients. In addition, four patients (4%) started participating in one or more sports postoperatively. For the OA group, 44 out of 54 patients (82%) could RTS compared to 21 out of 30 patients (70%) for the non-OA group (n.s.). Figure 3 presents the level of sports participation at four timepoints for the total group, showing a shift over time from a competitive/professional level to a recreational level. Compared to pre-symptomatically, sports frequency was lower 1 year pre- and postoperatively (Supplementary material 2). At final follow-up, frequency had increased again, but did not reach the pre-symptomatic level. A shift was found from high- to intermediate- and low-impact sports (Supplementary material 2). Sports ability at final follow-up compared to best lifetime sports ability was worse or much worse in 55 patients (60%), unchanged in 19 patients (20%) and improved or much improved in 19 patients (20%). The median Tegner score decreased from 4.0 (range 0–10) pre-symptomatically to 3.0 (range 0–10) at final follow-up (p < 0.01). The mean Lysholm score at final follow-up was 68 (± 22). In total, 42% of patients reported a Lysholm score of < 65 points (poor), 28% a score of 65–83 (fair), 23% a score of 84–94 (good) and 7% a score of > 94 (excellent).

Return to work

Before the onset of restricting knee symptoms, 80 patients (81%) were working, and 77 of them (77%) were still working 3 months preoperatively. Postoperatively, 73 out of 80 patients (91%) could RTW of whom 59 patients (81%) returned within 6 months. In addition, three patients started working postoperatively. In the OA group, 51 out of 54 patients (94%) could RTW, compared to 22 out of 26 patients (85%) in the non-OA group (n.s.) (Fig. 4). On average, patients worked an equal number of hours 1 year postoperatively compared to preoperatively and worked slightly more hours at final follow-up (Table 3). Table 4 presents the pre-symptomatic and preoperative workload, and postoperative changes in workload. Out of seven patients that did not RTW, four patients did not return due to knee complaints and three patients did not return due to physical complaints unrelated to their knee. Finally, Fig. 5 presents the WORQ scores at three timepoints. 3 months preoperatively, > 50% of patients experienced severe difficulty with kneeling, crouching, clambering and walking on rough terrain. Postoperatively, an improvement was observed for all activities. Walking on rough terrain and taking the stairs showed the largest improvement, while patients experienced most difficulty with kneeling and crouching.

Discussion

The most important findings of the present study were that 77% of patients could RTS after DFO, of whom 71% returned within 6 months. Furthermore, 91% of patients could RTW, of whom 81% returned within 6 months. There was no statistically significant difference in RTS and RTW between the subgroups of OA patients and non-OA patients.

The present study is the first to assess sports participation pre-symptomatically, 1 year pre- and postoperatively and at final follow-up, allowing for a good comparison of the effect of DFO on sports ability over time. Based on previous research [16, 32], a return to the pre-symptomatic sports level was considered unlikely for most patients. This was confirmed by the reported sports ability at final follow-up, which was worse or much worse in 60% of patients compared to their best lifetime sports ability. Still, 45% performed sports ≥ 2 times/week and 41% performed sports for ≥ 3 h/week. Finally, 45% of all sports activities performed at follow-up were intermediate- or high-impact activities. Compared to HTO, DFO patients showed a lower participation in high-impact activities (10 vs. 6%) and higher participation in intermediate-impact activities (32 vs. 39%) [16]. Nevertheless, participation in intermediate- and high-impact sports was considerably higher than after TKA (11%) and UKA (23%) [34]. This might be explained by more liberal surgeons’ advice as well as higher functional benefits after DFO compared to KA, given the fact that native knee structures are preserved [6].

In addition, the present study is the first to report time to RTS after DFO. Half of the patients returned within 15 weeks and 71% returned within 6 months. Thus, 29% of patients took longer than 6 months to RTS. In TKA, average time to RTS was 13 weeks, compared to 12 weeks in UKA [34]. Therefore, DFO appears to show a functional benefit from retaining native knee kinematics, allowing demanding functional loading that would otherwise jeopardize the survival of a KA [6, 35]. In contrast, time to RTS might be somewhat longer after DFO due to the extended rehabilitation following knee osteotomy [10].

Regarding RTW, almost all patients (91%) returned to work, which is high compared to reported numbers for surgical alternatives. Average RTW in HTO patients is 85% [16], and varies between 70 and 89% in TKA patients [15, 17, 21]. Yet, it must be noted that the mean age in our cohort was comparable to studies in HTO patients, and lower compared to studies in TKA patients. Furthermore, our study is the first to report time to RTW after DFO and found that 71% returned within 6 months. This is in line with findings in HTO patients, where the mean time to RTW was 16 weeks [16]. Given the higher mean age of the OA subgroup (49 vs. 28 years) and the presence of debilitating knee OA, it is remarkable that more patients appeared to return to work and time to RTW appeared shorter compared to the non-OA group. A possible explanation is that bone healing and functional recovery are faster after DFO for unicompartmental OA, compared to de-rotation osteotomies for rotational malalignment and combined femoral and tibial osteotomies, which were mainly performed in the non-OA group [10, 12, 13]. Concerning knee-demanding work activities, as anticipated, preoperatively patients experienced most difficulty with kneeling, crouching, clambering, walking on rough terrain and taking the stairs. One year postoperatively, the number of patients experiencing severe difficulties had decreased markedly for all work-related activities, except for crouching. These findings are consistent with those in TKA patients, who experienced severe difficulty with kneeling, crouching, clambering and taking the stairs preoperatively [17]. However, at 2–3 years follow-up, the total percentage of KA patients experiencing difficulties was higher for all activities, except for crouching, compared to DFO [17, 27]. These findings indicate that DFO may provide equal or better work-related functional outcomes compared to KA.

Given the limited number of studies on RTS and RTW after DFO, a comparison with previous literature is difficult. De Carvalho et al. found that, after varising DFO for unicompartmental OA, 14 out of 15 patients (93%) returned to their preoperative activity level and 23 out of 26 patients (89%) returned to work [4]. The authors found a median Tegner score of 3.0 (range 1–7) both pre- and postoperatively, compared to a median Tegner score of 4.0 (range 0–10) pre-symptomatically and 3.0 (range 0–10) postoperatively in the present cohort. Thus, RTS was slightly higher in De Carvalho’s cohort, while the Tegner score was higher in the present study. This difference cannot be explained by age distribution, which was similar in both groups, or surgical indication, since subgroup analysis of the OA group in the present study showed similar findings. Thus, no clear reason could be identified for the difference between both studies. Another study investigated RTS in 13 young athletes participating in high-impact sports ≥ 4 times per week. All athletes returned to their prior level, which is a promising finding, indicating that even a return to high levels of athletic activity is possible after DFO [31].

Finally, finding the optimal treatment strategy for the increasing number of young patients with “old knees”, who tend to have expectations that exceed the improvements a knee arthroplasty can deliver [1, 24], remains challenging. According to the algorithm proposed by Arnold et al., the highest priority in any affected knee should be a balanced mechanical leg axis [1]. Due to the high variety of indications and broad age range in our study population, our results are likely more generalizable to the total DFO population than previously reported results in young athletes and lateral OA patients [4, 31]. Consequently, these findings can be of use for shared decision making in a broader DFO population. The general view arising from current limited literature is that RTS and RTW after DFO is possible and might even be higher compared to surgical alternatives such as TKA and UKA.

An important limitation of the present study is the retrospective design, which makes our findings prone to recall bias. Future prospective studies are needed to control for this aspect and to further elaborate on the fulfilment of patients’ expectations after DFO. In addition, no validated questionnaire exists to ascertain participation in sport and work. To improve comparability, a sports questionnaire was used that has been previously described in patients undergoing TKA, UKA and HTO [8, 22, 23], and the validated Tegner and Lysholm score were added. For the work-related outcomes, the validated WORQ questionnaire was used to increase reliability and validity of our findings [9, 18].

Conclusion

In conclusion, almost eight out of ten patients return to sport and nine out of ten patients return to work after DFO. These are clinically relevant findings that further justify DFO as a surgical alternative to KA in young, active knee OA patients who wish to return to high activity levels.

References

Arnold MP, Hirschmann MT, Verdonk PCM (2012) See the whole picture: Knee preserving therapy needs more than surface repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20:195–196

Benhamou M, Boutron I, Dalichampt M, Baron G, Alami S, Rannou F, Ravaud P, Poiraudeau S (2013) Elaboration and validation of a questionnaire assessing patient expectations about management of knee osteoarthritis by their physicians: the Knee Osteoarthritis Expectations Questionnaire. Ann Rheum Dis 72:552–559

Briggs KK, Steadman JR, Hay CJ, Hines SL (2009) Lysholm score and Tegner activity level in individuals with normal knees. Am J Sports Med 37:898–901

Carvalho L, Temponi E, Soares L, Gonçalves M, Costa L (2014) Physical activity after distal femur osteotomy for the treatment of lateral compartment knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 22:1607–1611

Ekhtiari S, Haldane CE, De Sa D, Simunovic N, Musahl V, Ayeni OR (2016) Return to work and sport following high tibial osteotomy: a systematic review. J Bone Jt Surg Am 98:1568–1577

Elson DW, Dawson M, Wilson C, Risebury M, Wilson A (2015) The UK Knee Osteotomy Registry (UKKOR). Knee 22:1–3

Eshuis R, Lentjes GW, Tegner Y, Wolterbeek N, Veen MR (2016) Dutch translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Lysholm score and Tegner activity scale for patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 46:976–983

Faschingbauer M, Nelitz M, Urlaub S, Reichel H, Dornacher D (2015) Return to work and sporting activities after high tibial osteotomy. Int Orthop 39:1527–1534

Gagnier JJ, Mullins M, Huang H, Marinac-Dabic D, Ghambaryan A, Eloff B, Mirza F, Bayona M (2017) A systematic review of measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures used in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 32:1688–1697

van Heerwaarden R, Brinkman J-M, Pronk Y (2017) Correction of femoral valgus deformity. J Knee Surg 30:746–755

van Heerwaarden RJ, Hirschmann MT (2017) Knee joint preservation: a call for daily practice revival of realignment surgery and osteotomies around the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25:3655–3656

van Heerwaarden RJ, Hofmann S, Wagenaar F (2014) Doppelosteotomien von Femur und Tibia. In: Lobenhoffer P, van Heerwaarden R, Agneskirchner JDK (eds) Osteotomien Indikation—Plan—Oper mit Plattenfixateuren. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 200–211

van Heerwaarden RJ (2014) Rotationsosteotomien von Femur und Tibia. In: Lobenhoffer P, van Heerwaarden R, Agneskirchner JD (eds) Kniegelenknahe Osteotomien Indikation—Plan—Oper mit Plattenfixateuren. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 214–233

van Heerwaarden RJ, Spruijt S (2014) Die Suprakondyläre varisierende und valgisierende Femurosteotomie mit Plattenfixateur. Lobenhoffer P. In: van Heerwaarden R, Agneskirchner JD (eds) Kniegelenknahe Osteotomien Indikation—Plan—Oper mit Plattenfixateuren. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 180–198

Hoorntje A, Leichtenberg CS, Koenraadt KLM, van Geenen RCI, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Nelissen RGHH, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Kuijer PPFM (2018) Not physical activity, but patient beliefs and expectations are associated with return to work after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 33:1094–1100

Hoorntje A, Witjes S, Kuijer PPFM, Koenraadt KLM, van Geenen RCI, Daams JG, Getgood A, Kerkhoffs GMMJ (2017) High rates of return to sports activities and work after osteotomies around the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 47:1–26

Kievit AJ, van Geenen RCI, Kuijer PPFM, Pahlplatz TMJ, Blankevoort L, Schafroth MU (2014) Total knee arthroplasty and the unforeseen impact on return to work: a cross-sectional multicenter survey. J Arthroplasty 29:1163–1168

Kievit AJ, Kuijer PPFM, Kievit R, Sierevelt IN, Blankevoort L, Frings-Dresen MHW (2014) A reliable, valid and responsive questionnaire to score the impact of knee complaints on work following total knee arthroplasty: the WORQ. J Arthroplasty 29:1169–1175

Kuijer PPFM, Van Der Molen HF, Frings-Dresen MHW (2012) Evidence-based exposure criteria for workrelated musculoskeletal disorders as a tool to assess physical job demands. Work 41:3795–3797

Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Zhao K, Kelly M, Bozic KJ (2009) Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: National projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res 467:2606–2612

Leichtenberg C, Tilbury C, Kuijer P, Verdegaal S, Wolterbeek R, Nelissen R, Frings-Dresen M, Vliet Vlieland T (2016) Determinants of return to work 12 months after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 98:387–395

Naal FD, Fischer M, Preuss A, Goldhahn J, von Knoch F, Preiss S, Munzinger U, Drobny T (2007) Return to sports and recreational activity after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Am J Sports Med 35:1688–1695

Naal FD, Maffiuletti NA, Munzinger U, Hersche O (2007) Sports after hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Am J Sports Med 35:705–711

Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM (2009) Knee arthroplasty: are patients’ expectations fulfilled? A prospective study of pain and function in 102 patients with 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop 80:55–61

Salzmann GM, Ahrens P, Naal FD, El-Azab H, Spang JT, Imhoff AB, Lorenz S (2009) Sporting activity after high tibial osteotomy for the treatment of medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sport Med 37:312–318

Santaguida PL, Hawker GA, Hudak PL, Glazier R, Mahomed NN, Kreder HJ, Coyte PC, Wright JG (2008) Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Can J Surg 51:428–436

Scott CEH, Turnbull GS, MacDonald D, Breusch SJ (2017) Activity levels and return to work following total knee arthroplasty in patients under 65 years of age. Bone Joint J 99B:1037–1046

Seil R, van Heerwaarden RJ, Lobenhoffer P, Kohn D (2013) The rapid evolution of knee osteotomies. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21:1–2

Vail T, Mallon W, Liebelt R (1996) Athletic activities after joint arthroplasty. Sports Med Arthrosc 4:298–305

Verbeek J, Mischke C, Robinson R, Ijaz S, Kuijer P, Kievit A, Ojajärvi A, Neuvonen K (2017) Occupational exposure to knee loading and the risk of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis. Saf Health Work 8:130–142

Voleti PB, Wu IT, Degen RM, Tetreault DM, Krych AJ, Williams RJ (2017) Successful return to sport following distal femoral varus osteotomy. Cartilage. https://doi.org/10.1177/1947603517743545

Warme B, Aalderink K, Amendola A (2011) Is there a role for high tibial osteotomies in the athlete? Sports Health 3:59–69

Witjes S, van Geenen RC, Koenraadt KL, van der Hart CP, Blankevoort L, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Kuijer PPFM (2017) Expectations of younger patients concerning activities after knee arthroplasty: are we asking the right questions? Qual Life Res 26:403–417

Witjes S, Gouttebarge V, Kuijer PPFM, van Geenen RCI, Poolman RW, Kerkhoffs GMMJ (2016) Return to sports and physical activity after total and unicondylar knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 46:1–24

Wylie JD, Jones DL, Hartley MK, Kapron AL, Krych AJ, Aoki SK, Maak TG (2016) Distal femoral osteotomy for the valgus knee: medial closing wedge versus lateral opening wedge: a systematic review. Arthroscopy 32:2141–2147

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ahmed Bayoumy, Elise Bonvie – Van Lammeren and Mariëlle van Echtelt for their assistance with data collection.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH drafted the protocol, collected data, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. PPFMK, BTG and KK assisted with the design of the study, participated in the coordination and helped to analyse data and draft the manuscript. RCIG, GMMJK and RJH helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the local medical ethical review board (Academic Medical Center Amsterdam, reference number W17_382 #17.448) prior to initiation of this study.

Informed consent

All patients provided written informed consent.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoorntje, A., van Ginneken, B.T., Kuijer, P.P.F.M. et al. Eight respectively nine out of ten patients return to sport and work after distal femoral osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27, 2345–2353 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-5206-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-5206-x