Abstract

The effectiveness of arthroscopic pump systems has been investigated with either subjective measures or measures that were unrelated to the image quality. The goal of this study is to determine the performance of an automated pump in comparison to a gravity pump based on objective assessment of the quality of the arthroscopic view. Ten arthroscopic operations performed with a gravity pump and ten performed with an automated pump (FMS Duo system) were matched on duration of the surgery and shaver usage, type of operation, and surgical experience. Quality of the view was defined by means of the presence or absence of previously described definitions of disturbances (bleeding, turbidity, air bubbles, and loose fibrous tissue). The percentage of disturbances for all operations was assessed with a time-disturbance analysis of the recorded operations. The Mann–Whitney U test shows a significant difference in favor of the automated pump for the presence of turbidity only (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.015). Otherwise, no differences were determined (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] > 0.436). A new objective method is successfully applied to assess efficiency of pump systems based on the quality of the arthroscopic view. Important disturbances (bleeding, air bubbles, and loose fibrous tissue) are not reduced by an automated pump used in combination with a tourniquet. The most frequent disturbance turbidity is reduced by around 50%. It is questionable if this result justifies the use of an automated pump for straightforward arthroscopic knee surgeries using a tourniquet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During arthroscopic surgery, the joint is continuously irrigated with saline fluid which is pressurized to create joint distension. The saline fluid flow removes disturbances in the arthroscopic view such as bleeding, air bubbles or synovial fluid. This improves the visibility of the arthroscopic view, which is an essential condition to perform an operation safe and fast. In this light, the quality of arthroscopic view has been defined as good or optimal if no disturbances are present [11]. In clinical practice, disturbances cannot always be prevented and maintaining a clear view is sometimes difficult [7, 10]. In a recent study performed by the authors, post-procedure analysis of 20 routinely performed arthroscopic knee procedures showed that 6% (SD 4%) of the total operation time was solely dedicated to obtaining a clear view. Since the number of arthroscopic procedures is large and still growing (60,000 per year in the Netherlands [8], and 1.7 million meniscectomies alone per year worldwide [3]), reducing the operating time by optimizing the view would be desirable.

The quality of the arthroscopic view is dependent on a number of factors such as the type of pump system, instruments, and condition of the joint [11]. In this study, the focus is on the type of pump system. The classical gravity pump and (automated) volumetric pumps are available for irrigation [10]. The main differences between these pumps are that the gravity pump causes a pressure due to a height difference caused by an elevated fluid bag and is manually controlled, whereas the volumetric pumps cause a fluid flow and have some type of automated pressure control. Since the automated pumps are regulated, in theory they should perform better in irrigation in the sense that the percentage of disturbed view over time should be less. In literature, the effectiveness of automated pump systems has been investigated [2, 4–6]. However, only subjective measures were used, such as visual clarity on a three-point scale or measures that were unrelated to the image quality, such as the number of fluid bags. The goal of this study is to determine the performance of an automated pump in comparison to the gravity pump based on objective assessment of the quality of the arthroscopic view. Therefore, a quantitative time-disturbance analysis was performed with uniquely described definitions for the different types of disturbances [11].

Methods

Only routinely performed procedures were included such as meniscectomy, cyst removal, debridement of a partial rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament, and diagnostic arthroscopy. Cruciate ligament reconstructions were not included. The patients were not notified of the recordings, because the operation was not affected and the patients’ identities could not be traced from the videos. No power analysis could be performed for this study, because no information was available on the variation of the disturbances. In accordance with other studies, it was decided to use ten operations for each of the two pump systems (20 in total) [2, 4]. The matching criteria were the number of operations, the duration of the operations, the duration of shaver usage, the type of operation, and the working experience of the surgeons. Matching of the shaver duration was performed, because some disturbances were expected to occur more frequently when using the shaver. Besides, a shaver is often used to clarify the view by temporarily increasing the flow. All surgeons who performed the operations had the same education and comparable working experience.

Ten arthroscopic knee procedures for which the gravity pump was used were recorded at 6 days within a time frame of 2 months. From the operations that met the inclusion criteria, ten were selected with randomization tables. Ten arthroscopic knee procedures performed with an automated pump were matched postoperatively to eliminate factors other than the irrigation pump systems that influence the arthroscopic view (Table 1).

The recordings of operations with a gravity pump were performed in the day care centre of Academic Medical Center (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The recordings of operations with an automated pump were performed in the day care centre of the Sint Maartenskliniek (Nijmegen, The Netherlands). The latter hospital utilizes the automated FMS Duo pump (FMSGroup, Nice, France). Table 2 shows the details on the standard operation setting for both hospitals using the different pumps. Most disturbances are more or less independent of the quality of the camera, the light source, and the arthroscope. It was assumed that these devices were functioning properly at the time of recording, because all operations were executed in acknowledged hospitals, in which the technical service department routinely inspects the equipment. A tourniquet was routinely applied at the start of the arthroscopic knee operations with a vacuum level of 300 mmHg. Drills, vaporizing devices, microfracturing, arthroscopic drills or meniscal repair devices were not used.

The comparison of the pumps was conducted by assessing the quality of the arthroscopic view per operation. Extending the definition of arthroscopic image quality by Tuijthof et al. [11] to the setting of irrigation performance of the pump systems, it is proposed that the pump for which the least percentage of disturbances occurs is the most effective. Seven disturbances of the arthroscopic view have been uniquely described and defined [11]. Not all of them can be prevented or removed by irrigation. Therefore, a subset of these disturbances was chosen for comparison of the pump systems: bleeding, turbidity (caused by synovial fluid and debris, Fig. 1), air bubbles, and loose fibrous tissue. The same recording equipment and quantitative time-disturbance analysis was performed as described in Tuijthof et al. [11]. Therefore, the recordings of the operations were analyzed frame by frame to assess the presence of the four disturbances in each frame. In addition to the total operation time, each operation was divided into phases to assess dominant prevalence of disturbances in a particular phase: (1) creation of portals, (2) joint inspection with or without a probe, (3) cutting, and (4) shaving. Phase 1 was the time required to achieve access to the joint by means of the arthroscope; thus the period from the first frame of the recorded digital video until the frame where a clear sharp arthroscopic view is presented for the first time. Added with this period is the time required to create the second and third portal: the period from the frame where the tip of a needle is seen for the first time until the frame where the tip of an instrument occurs. Phases 3 and 4 were defined as the frames in which the specific instrument was present in the arthroscopic view. The remainder of the operation time was indicated as Phase 2 inspection.

The 20 digital videos were analyzed by two testers who each assessed an equal number of operations of each group. Their tester agreement was determined prior to the time-disturbance analyzes by means of the adjusted kappa [1, 9]. For each of the four disturbances, the adjusted kappa was larger than 0.80 indicating good agreement. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 12.0.2 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The presence of a normal distribution for both datasets was determined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. With the help of a one-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA) significant statistical differences were assessed in case the data were normally distributed. Otherwise, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test (Wilcoxon rank sum test) was applied.

Results

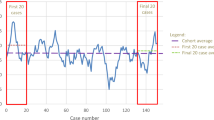

Almost 3 h of digital video material has been analyzed for both groups (Table 1). The mean operation time is around 18½ min for the gravity pump, and 17½ min for the automated pump. In each pump group, the total time of shaver usage is around 23% (Table 1). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests show that the datasets are not distributed normally. As a consequence, the results of the percentages of each disturbance of the total operation time are presented with the median, minimum and maximum (Fig. 2). The disturbances show a substantial variation per operation. Turbidity was the dominant disturbance in both pump groups (median of 18% of the total operation time for the gravity pump versus 8% for the automated pump). The Mann–Whitney U test shows a significant difference for the presence of Turbidity (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.015) between both pump groups in favor of the automated pump. No significant differences are found for the other three disturbances (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] > 0.436) (Fig. 2).

Results of the share of disturbances in the arthroscopic view as percentage of the total operation time for each operation and each of the two groups. The results are presented with the median, minimum, and maximum numbers, because the datasets were not distributed normally. *The Mann–Whitney U test shows a significant difference for Turbidity (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.015)

Not all of the four operation phases were present in the 20 operations. Phases 3 and 4 were absent in both diagnostic arthroscopies. Additionally, punches were not used in five operations in the gravity pump group, and three in the automated pump group. As was expected the creation of portals was the shortest phase (10% for the gravity pump versus 5% for the automated pump), and inspection was the longest phase (59% for the gravity pump versus 51% for the automated pump). Punches were used more frequently in the automated group (7% for the gravity pump versus 21% for the automated pump). Analyzing each of the four operation phases separately shows a significant difference in favor of the automated pump for Turbidity in Phase 2 (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.019). For all other disturbances and operation phases no significant differences are determined (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] > 0.165). The Mann–Whitney U test within each of the pump groups shows a significant difference for loose fibrous tissue (Fig. 3). In detail, the gravity pump shows the following results: Phase 1 versus 3 (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.002), Phase 1 versus 4 (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.010), and Phase 2 versus 3 (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.002). The automated pump shows these results: Phase 1 versus 2 (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.017), Phase 1 versus 3 (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.001), and Phase 2 versus 3 (Exact Sig. [2*(1-tailed Sig.)] = 0.022).

Results of the share of disturbances in the arthroscopic view as percentage of the phase time for each operation in the gravity pump group (a), and the automated pump group (b). The results are presented with the median, minimum, and maximum numbers, because the datasets were not distributed normally. *The Mann–Whitney U test shows only a significant difference for loose fibrous tissue in both pump groups

Discussion

The objective of this study was to compare two types of irrigation pump systems (the classic gravity pump and a widely used automated pump) based on their effectiveness in maintaining a clear arthroscopic view. Comparison of the effectiveness of pump systems has been performed [2, 4–6]. However, none of these studies measured the arthroscopic image quality objectively in detail. Besides the objective comparison, the time-disturbance analysis gave quantitative values for the frequency of four disturbances.

Turbidity was the dominant disturbance in both pump groups being present in a considerable percentage of the operation time (Fig. 2). The results show that for routinely performed arthroscopic knee operations, the automated pump was significantly more effective in reducing the presence of turbidity with 50% on average. This finding can be explained by the continuous flow of 90 ml/min that is activated by the automated pump as opposed to the lower flow cause by leakage along the portals when using the gravity pump and a two-portal technique. No difference was determined for the other three disturbances. The low percentage of bleeding can be attributed to the use of a tourniquet in all operations. In order to determine the effectiveness of pump systems for this disturbance, analysis of shoulder surgeries would be more convenient.

The found variation in the duration of disturbances per operation could have been caused by the condition of the knee joints, because this factor could not be completely eliminated with precise matching. With this knowledge, a future suggestion is to analyze a larger number of patients per pump group to determine possibly other significant differences in pump performance.

Comparison of the operation phases independently showed similar results for the inspection phase compared to the total operation time, probably because this was the longest phase. Since the creation of portals was a relatively short phase, and the use of punches was absent for almost half of the operations, no significant differences were found. However, analysis of both groups internally showed that the presence of loose fibrous tissue was generally significantly higher in when an instrument was used (Phases 3 and 4). This is in accordance with the general expectation and confirms the applicability of this method for quantification of disturbances in the view.

Concluding, this study shows that important disturbances as bleeding, air bubbles, and loose fibrous tissue are not affected by a pump system when performing a routine knee arthroscopy with a tourniquet. The most frequent disturbance turbidity is reduced by around 50% when using an automated pump. It is questionable if this justifies the use of an automated pump for straightforward arthroscopic knee surgeries using a tourniquet, since the purchase of an automated pump is more costly.

References

Altman DG (1991) Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 404

Ampat G, Bruguera J, Copeland SA (1997) Aquaflo pump vs FMS 4 pump for shoulder arthroscopic surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 79:341–344

Baker BS, Lubowitz J (2006) Meniscus injuries. eMedicine 22-11-2006

Dolk T, Augustini BG (1989) Three irrigation systems for motorized arthroscopic surgery: a comparative experimental and clinical study. Arthroscopy 5:307–314

Muellner T, Menth-Chiari WA, Reihsner R, Eberhardsteiner J, Engebretsen L (2001) Accuracy of pressure and flow capacities of four arthroscopic fluid management systems. Arthroscopy 17:760–764

Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Weisleder L (1995) Fluid pump systems for arthroscopy: a comparison of pressure control versus pressure and flow control. Arthroscopy 11:591–595

Oretorp N, Elmersson S (1986) Arthroscopy and irrigation control. Arthroscopy 2:46–50

Prismant Internet (2002) Research, advise, information and education in health care, Utrecht. http://www.prismant.nl

Sim J, Wright CC (2005) The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther 85:257–268

Tuijthof GJ, Dusee L, Herder JL, van Dijk CN, Pistecky PV (2005) Behavior of arthroscopic irrigation systems. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 13:238–246

Tuijthof GJM, Sierevelt IN, van Dijk CN (2007) Disturbances in the arthroscopic view defined with video analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 15:1101–1106

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Technology Foundation STW, applied science division of NWO and the technology program of the Ministry of Economic Affairs, The Netherlands. The authors wish to thank the personnel of the day care centers of the Academic Medical Centre (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and the Maartenskliniek (Nijmegen, The Netherlands) for giving the opportunity to record the operations.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tuijthof, G.J.M., van den Boomen, H., van Heerwaarden, R.J. et al. Comparison of two arthroscopic pump systems based on image quality. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthr 16, 590–594 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-008-0513-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-008-0513-2