Abstract

This study assesses the causal effect of child marriage on infant mortality. Using age discontinuities in exposure to a law that raised the legal age of marriage for women in Ethiopia, the study estimates that a 1-year delay in a woman’s age at cohabitation during her teenage years reduces the probability of her first-born child dying during infancy by 3.8 percentage points. This impact is closely linked to the effect of delaying cohabitation on women’s age at first birth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 2014, UNICEF reported that more than 700 million women worldwide first cohabited with a partner before the age of 18, with the vast majority living in developing countries (UNICEF 2014). Considered by UNICEF a form of violence against women, the practice of underage cohabitation, also known as child marriage, is associated with worse health, education, labor force participation, offspring mortality, and participation in household decisions (Parsons et al. 2015).Footnote 1 In recent decades, decreasing the prevalence of this practice has become a priority for policy-makers of international organizations and developing countries. Moreover, most of the countries with a high prevalence of child marriage have ratified various international agreements, such as the CEDAW, the CCMMAMRM, and the Maputo Protocol that promote the enactment and enforcement of minimum-age-of-marriage laws.Footnote 2 The fight against child marriage has also mobilized considerable resources through integrated programs and national alliances targeting the cultural, social, and economic causes of this widespread practice. Although the overall prevalence of child marriage is declining over time, the eradication of this practice is currently far from becoming a reality (UNICEF 2014; Jensen and Thornton 2003).

One of the countries that has embraced the battle against child marriage is Ethiopia. The flagship measure of the Ethiopian federal government aimed at addressing this problem is the Revised Family Code (RFC), which was approved in July 2000. This law raised the legal age of marriage for females from 15 to 18 years in some regions of Ethiopia, while leaving the legal age of marriage for men unchanged at age 18. The law banned underage marriage rather than underage cohabitation. However, since unmarried cohabitation is heavily stigmatized in Ethiopia (Jones et al. 2016), it is plausible that the increase in the legal age of marriage for women has resulted in an increase in the age at cohabitation. This study uses age discontinuities in the degree of exposure to the RFC as an exogenous source of variation in women’s age at cohabitation to investigate the causal effect of delaying cohabitation during a woman’s teenage years on the probability that her first-born child will die in infancy, while also assessing the mechanisms through which early cohabitation might affect infant mortality.

The novelty of the analysis presented in this study is based on three main contributions. First, reducing child marriage and infant mortality are central priorities in the policy agenda of many developing countries (Weldearegawi et al. 2015), and the literature has documented the positive association between these two outcomes (Raj et al. 2010). However, since it is possible that the association that these studies detected was driven by unobservable factors, the extent to which child marriage has been contributing to the high prevalence of infant mortality in many developing countries remains unclear. In this study, I add to the thin body of evidence that rigorously explores the latter question (Chari et al. 2017) by documenting the perverse causal effect of child marriage on infant mortality in Ethiopia and by investigating the mechanisms driving this link. Second, although my identification strategy does not allow me to estimate the causal effect of raising the legal age of marriage, the results of my analysis suggest that many women reacted to the increase in the legal age of marriage by postponing cohabitation. The latter finding indicates that even in contexts where the capacity of the state to enforce the law is limited, legal reforms can help to tackle cultural practices that are deeply rooted in tradition. Third, unlike previous studies that used age at menarche as an instrumental variable for child marriage, I address endogeneity in the link between women’s age at cohabitation and socioeconomic outcomes by exploiting age discontinuities in the effective legal age of marriage for Ethiopian females. Using information on women’s month and year of birth from the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), I apply a fuzzy regression discontinuity design (RDD) that exploits the fact that women who were under age 15 when the RFC was introduced were exposed to a legal age of marriage at age 18, whereas women who were age 15 or older when the RFC was introduced had the opportunity to legally marry before they turned 18. The increase in the age at cohabitation that was caused by being fully exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18 is then used as an instrumental variable to estimate the causal effect of delaying cohabitation on the probability of a woman’s first-born child dying in infancy.

The estimates for the causal effect of child marriage reveal that, on average, a 1-year delay in a woman’s age at cohabitation during her teenage years decreases the probability of infant mortality for her first-born child by 3.8 percentage points. This is a substantial effect given the mean of 10%. These results are robust to the use of different bandwidths, estimation techniques, and identification strategies, including a difference-in-differences design that exploits the staggered introduction of the law across Ethiopia. Additionally, the results of various placebo tests rule out the possibility that the impact on infant mortality was driven by other legal provisions included in the RFC or other policy interventions implemented around the same time, systematic differences between women born in different months of the year, systematic manipulation of the age reported in the survey, selective migration, or secular trends in infant mortality.

The results of the analysis of mechanisms indicate that the impact of delaying a woman’s age at cohabitation on the probability of infant mortality for her first-born child is mainly channeled through the positive effect of delaying cohabitation on the age of the woman at first birth. Other possible channels such as an effect of early cohabitation on woman’s education, marriage market outcomes, labor market outcomes, and participation in household decisions are explored and dismissed in the light of the evidence.

The study is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on the socioeconomic effects of child marriage. Section 3 discusses the incidence of child marriage in Ethiopia and presents the law that raised the legal age of marriage for women from 15 to 18 years in some regions of the country. Section 4 introduces the identification strategy and Section 5 describes the data used in the main analysis. Section 6 presents the main results, examining their robustness to the use of alternative estimation methods, bandwidths, and placebo tests. Section 7 investigates the channels through which early cohabitation could affect infant mortality. Finally, Section 8 concludes the study.

2 Related literature

Several previous studies have explored the link between child marriage and socioeconomic outcomes for women and their children. A synthesis of this literature is provided in Parsons et al. (2015). The review concludes that, overall, child marriage is associated with harmful socioeconomic outcomes for women, including lower levels of participation in household decision-making and worse marriage market outcomes (Jensen and Thornton 2003; Jain 2007; Solanke 2015; Wang and Wang 2017; Blackburn et al. 1993), lower levels of labor force participation and educational attainment (Elborgh-Woytek et al. 2013; Jensen and Thornton 2003; Nguyen and Wodon 2015; Wodon et al. 2016), and worse maternal health (Campbell 2002). The review also suggests that child marriage is associated with higher fertility, teenage pregnancy, and a lower age at first birth (Jensen and Thornton 2003; Solanke 2015); all of which are factors that have been linked to early mortality (see, for example, Weldearegawi et al. (2015)). Indeed, child marriage is associated with negative health outcomes and a higher prevalence of infant mortality among the children of these women (UNICEF 2014; Wachs 2008; Raj et al. 2010).

These studies examined the correlation between child marriage and the socioeconomic outcomes of these women and their children. This approach could be problematic because the statistical association between child marriage and these outcomes might have been driven by reverse causality or by unobservable factors correlated with both. A few studies have addressed this problem empirically by exploiting the age at menarche as an instrumental variable for women’s age at marriage. These studies have shown that the arrival of puberty determines a woman’s entrance into the marriage market, and that a delay in the age at menarche significantly increases the age at marriage among women. Using this approach, Field and Ambrus (2008), Asadullah et al. (2016), and Hicks and Hicks (2015) found that early marriage decreases educational attainment for women and antenatal health investments in Bangladesh, India, and Kenya. Using the same instrumental variable approach, Chari et al. (2017), Sekhri and Debnath (2014), Asadullah et al. (2016), and Asadullah and Wahhaj (2018) documented for India and Bangladesh that early marriage also has intergenerational effects, including negative effects on the educational attainment, cultural values, and health investment levels among the children of women who married young. On the other hand, Hicks and Hicks (2015) did not find any effect of early marriage on the labor market outcomes, beliefs, and marriage market outcomes of women in Kenya. Finally, Chari et al. (2017) found that while child marriage decreases birth weight, they did not observe any significant effect on infant mortality, although the authors mentioned that the analysis of this outcome might be underpowered. The main identification condition of the studies using this method is that conditional on covariates, age at menarche should not affect socioeconomic outcomes other than through its effect on the age at marriage. This paper employs an alternative identification strategy to address endogeneity concerns, namely a fuzzy regression discontinuity approach that exploits age discontinuities in the degree of exposure to a law that changed the legal age of marriage.

Finally, a related body of research has contributed to the debate on the consequences of child marriage by evaluating the impact of interventions that tackle this practice. For example, Field et al. (2008) found that financial incentives and empowerment programs targeting adolescent girls reduced child marriage in Bangladesh, increased the girls’ educational levels, and delayed their age at first birth. Similarly, Bandiera et al. (2018) showed that an empowerment intervention targeting adolescent girls in Uganda led to decreased rates of child marriage and teen pregnancy and improvements in women’s rates of participation in income-generating activities. By contrast, Nanda et al. (2016) found that a cash transfer program in India that was awarded to families that do not marry their daughters before the age of 18 did not have any effect on child marriage. Belles-Obrero and Lombardi (2020) showed that the increase in the legal age of marriage in Mexico, a country with a high incidence of unmarried cohabitation, decreased early marriages but increased early cohabitation, with null effects on teenage pregnancies. The potential effects of child marriage on infant mortality were not explored in these studies.

3 Child marriage in Ethiopia and the Revised Family Code

In Ethiopia, around 1,974,000 women cohabit before the age of 18, which makes Ethiopia the country with the fifth-highest number of child marriages in the world.Footnote 3 The evolution of this practice over time is graphically displayed in Fig. 9 in the Appendix, and reveals that child marriage is still common among young Ethiopian girls. Aware of this problem, raising the age at cohabitation for women has been a priority for policy-makers in Ethiopia for decades. Following the ratification of the CEDAW, which encourages governments to enact and enforce laws and programs aimed at delaying cohabitation, the Federal Government of Ethiopia approved the Revised Family Code (RFC) in July 2000. This law established the legal age of marriage at 18 years for both men and women.

Before the Federal Government of Ethiopia passed the RFC, the legal age of marriage for women and men was regulated by the 1960 Family Code. This earlier law set the legal age of marriage at 15 for females and at 18 years for males. Thus, while the RFC raised the legal age of marriage for females from 15 to 18 years, it left unchanged the minimum age of marriage for men at 18 years. At the same time, the RFC recognized the validity of marriages that occurred before the approval of the RFC that complied with the 1960 Family Code. Additionally, the RFC granted women the authority to administer common marital property, abolished the right of a husband to forbid his wife to work outside the home, and facilitated divorce. The effects of the RFC have been investigated by Hallward-Driemeier and Gajigo (2015). The latter paper used a difference-in-differences design to show that the reform increased women’s participation in out-of-house occupations and improved the quality of their jobs. The effects of these additional legal provisions are unlikely to be confounding my results. Although these changes in the law might have impacted infant mortality in ways other than through an increase in the age at cohabitation, they plausibly affected similarly girls just below and just above the cut-off. I examine this hypothesis in Section 6.3, and find reassuring results.

The initial approval of the RFC by the Federal Government of Ethiopia in July 2000 did not lead to the immediate implementation of the law throughout the country. As family law is under the jurisdiction of the regional governments, the RFC initially applied only to the chartered cities of Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa. The application of the law in all other Ethiopian regions required the approval of each regional government. The staggered rollout of the RFC across the 11 Ethiopian regions is detailed in Table 7 in the Appendix.

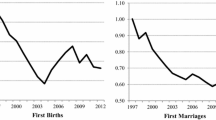

Based on 2011 DHS data, Fig. 1 shows the distribution of the age at first cohabitation for women who were 12–14 years old and for women who were 15–17 years old when the RFC was implemented in their region. The legal age of marriage differed for these two groups of girls. While the cohort of girls who were aged 12–14 when the legal age of marriage was raised from 15 to 18 could not legally marry until they reached the age of 18, the cohort of girls who were 15–17 when the RFC was approved were permitted to legally marry at the age of 15 at least for some period of time before the introduction of the RFC increased the legal age of marriage. The figure shows that the distribution of the age at first cohabitation shifted to the right for the cohort of girls who were aged 12–14 when the RFC was approved, and who were thus fully exposed to a legal age of marriage at the age of 18. The figure also shows that the most frequent age at first cohabitation coincides with the legal age of marriage to which each cohort was exposed (15 for the older cohort and 18 for the younger cohort).

Although this is a large shift, the increase in the mean age at cohabitation between these two cohorts could be partially explained by a secular increase in the age at cohabitation over time. Figure 2 provides additional evidence regarding the degree to which this shift is caused by the new law. Using 2011 DHS data, the graph shows the probability of child marriage, which is defined as the probability of starting cohabitation before reaching age 18, by the age of the girl when the RFC was introduced in the region. The graph shows that the probability of child marriage for women who were slightly younger than 15 years old when the law was introduced—and who thus could not legally marry until they turned 18—was 15–20 percentage points lower than it was for women who were slightly older than 15 when the RFC was approved—and who thus had the opportunity to legally marry at the age of 15 for some period of time before the approval of the law. Furthermore, Fig. 12 in the Appendix indicates that the magnitude and the relevance of the discontinuity at the cut-off are robust to the use of alternative functional forms for the forcing variable. Taken together, these results suggest that exposure to a legal age of marriage of 18 decreased the prevalence of child marriage and increased the mean age at cohabitation for the women in the regions analyzed. Furthermore, the sharp drop in the probability of child marriage among girls who were just under age 15 when the RFC was introduced, and the fact that the most frequent age at cohabitation in each cohort was the legal age of marriage to which they were exposed, may indicate that the minimum ages of marriage set in the 1960 and 2000 Family Codes were enforced to some extent. In Section 6.1, I examine whether the increase in the mean age at cohabitation for the girls in the analytical sample who were exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18 is sufficiently large and statistically relevant to validate the causal estimations conducted in the study.

Child marriage (probability of underage cohabitation) by age when the Revised Family Code was introduced. Note: Following UNICEF, child marriage is defined as the probability of starting cohabitation before reaching the age of 18 years old. This figure is constructed using the sample of women in the 2011 Ethiopian DHS that are at least 18 at the time of the survey and lived in one of the five Ethiopian regions that are included in the analysis, regardless of whether have ever cohabited with a partner or have children. Mean size of the bin is 190 observations

At the same time, the figures confirm that the percentage of women who were cohabiting with a partner before they reached the minimum legal age of marriage is non-negligible among women who were exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18. There are multiple reasons why the introduction of the RFC has not eradicated child marriage. First, the institutional capacity to enforce the law is limited, particularly in rural areas, where the power of state administrative bodies is weak (Jones et al. 2016).Footnote 4 Second, although the law provides that the official or the priest celebrating the wedding has to verify that both the bride and the groom are at least 18 years old, the lack of birth and school registers for large shares of the population makes this verification process difficult (Jones et al. 2016). Finally, although the RFC bans civil, religious, and customary marriages before age 18, unmarried cohabitation prior to this age (which is one form of child marriage) is not explicitly forbidden in the law, which may lead to an increase in unmarried cohabitation among girls (Belles-Obrero and Lombardi 2020). However, unmarried cohabitation is unlikely to play a large in role in the Ethiopian context, as it is heavily stigmatized (Jones et al. 2016).

4 Identification strategy

The RFC raised the legal age of marriage for females in Ethiopia from 15 to 18 years. This legal change resulted in variation in the legal age of marriage that applied to females of different ages. First, women who were younger than 15 years old when the RFC was approved in their region could not marry legally until they reached the age of 18. Second, women who were older than 18 years old when the RFC was approved were not directly affected by the change in the legal age of marriage. Third, women who were between 15 and 18 years old when the RFC was introduced were exposed to a legal age of marriage at 15 years for at least some period of time after their 15th birthday. Thus, these women had the opportunity to marry legally before they reached the age of 18. For this group of women, the announcement of the RFC could have caused them to marry at a younger age than they otherwise would have. For example, an unmarried woman who was aged 15 years and 6 months when the RFC was introduced had 6 months to marry legally at the age of 15 prior to the law’s approval. If she did not marry during that window, she was not able to legally marry until she turned 18. Thus, among girls who were 15–18 years old when the RFC was approved, the older a girl was, the longer her post-15 period of exposure to a legal age of marriage at 15 and the smaller the potential was for the change in the law to have advanced her age at first cohabitation.

My identification strategy relies on the change in the mean age at cohabitation for females who were just above age 15 at the time the law was introduced, and who therefore had the opportunity to legally marry at the age of 15 before the introduction of the RFC; relative to the mean age at cohabitation for females who were just under 15 when the RFC was approved, and who could not legally marry until they reached the age of 18. Rather than on the lack of effect for females older than 15, the causal interpretation of the effect of age at cohabitation on infant mortality relies on a differential effect of the law on the age at cohabitation of women who were just above and just below the age of 15 when the RFC was introduced. If the mean age at cohabitation increases sharply for women who were younger than 15 when the RFC was approved, the setting would be ideal for the implementation of a fuzzy regression discontinuity design (RDD) that uses the age of the woman at the time the RFC was introduced as the forcing variable.

My regression discontinuity design has four distinctive features. First, as stated above, the age distance to the cut-off (how many months older or younger than age 15 a female was when the RFC was introduced) may itself have an effect on the age at cohabitation, which might be different on either side of the cut-off. Although this is, in principle, not a binding constraint, it is important to use a flexible function for the forcing variable that can accurately capture this relation at every point.

Second, while the change in the law hindered underage marriage, it did not eradicate the practice of child marriage.Footnote 5 In other words, having been exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18 did not necessarily mean that all of these females delayed cohabiting until they reached age 18.

Third, the forcing variable is the age of the woman at the time the legal age of marriage was increased, measured in months, with the cut-off at the age of 15 years. The women who turned 15 in the month in which the RFC was approved were dropped from the sample used in the analysis because the DHS survey only collected information on the month and the year of birth, and it is therefore impossible to determine whether these women turned 15 before or after the RFC was approved.

Fourth, the RFC was not applied simultaneously throughout Ethiopia. The differences across regions in the timing of the increase in the legal age of marriage provide variation in the current ages of women who were approximately 15 years old when the RFC was approved in their region.Footnote 6 Because in this RDD setting the causal estimates are only identified for women who were around the cut-off, the variation across regions in the age of women at the cut-off makes the RDD estimates relevant to women of different ages. Furthermore, I exploit the staggered introduction of the law across Ethiopian regions in a difference-in-differences design to check the robustness of the results to an alternative identification strategy. The results of this analysis are reported in Table 15 in Appendix 2. The magnitudes of the coefficients are very similar to those obtained in our preferred RDD and are statistically significant at conventional confidence levels. However, I believe that the RDD design used has an important advantage. Although it is statistically significant at 5%, the first stage in the difference-in-differences analysis does not meet the relevance threshold (F > 10) typically used in the literature, which may lead to a problem of weak instruments (Bound et al. 1995).

To estimate the effect of a woman’s age at cohabitation on the probability of her first-born child dying in infancy, I followed a two-stage procedure. In the first stage, I estimate the following regression to examine whether girls who were slightly older and slightly younger than age 15 at the time the law was approved started cohabiting at different ages:

where Age at Cohabi indicates the age of woman i at first cohabitation, Age at RFC< 15 is a binary variable that indicates whether the woman was younger than 15 when the RFC was approved in her region, and was therefore exposed to an effective legal age of marriage of 18 years. X is a vector of control variables, including region, ethnic, and religion fixed effects, the age of the woman at the time of the survey, the gender of the first-born child, and a dummy variable indicating whether the woman was living in a rural area. These are variables that correlate with the probability of infant mortality and that were arguably unaffected by the RFC. F(Age at RFC) is a function of the age of the woman in months measured at the date when the legal age of marriage was raised in her region.

Then, I use the predicted age at cohabitation from Eq. 1 to estimate the following regression:

where InfantMortalityi is a dummy variable equal to one if the first-born child of woman i died within the first year of life; and \(\widehat {\text {\textit {Age at Cohab.}}_{i}}\) is the predicted age at cohabitation for woman i estimated from Eq. 1.

Equation 1 is the first-stage regression. The parameter α1 measures the effect of the exposure to a legal age of marriage of 18 on the age at first cohabitation, relative to having been given the opportunity to legally marry at the age of 15 for a few months before the introduction of the RFC. It should therefore be noted that α1 cannot be interpreted as the effect on the age at cohabitation of exposure to a legal age of marriage of 18 relative to 15. Instead, it measures the differential effect of the RFC on females on either side of the cut-off. Equation 2 is the second-stage equation and the regression of primary interest. The parameter β1 yields the effect of a 1-year delay in a woman’s age at cohabitation during her teenage years on the probability of infant mortality for her first-born child.

I estimate (1) and (2) using non-parametric local polynomial regressions based on triangular kernel functions. I follow the state-of-the-art procedure described by Calonico et al. (2014, 2016) for the selection of the optimal bandwidth and for the calculation of bias-corrected RD estimates with robust variance estimator. Standard errors are clustered at the running variable level, as recommended by Lee and Lemieux (2010). I examine the robustness of the results to the use of (a) two alternative bandwidths equal to 0.75 and 1.5 times the optimal bandwidth, (b) conventional and bias-corrected non-parametric RD estimation procedures with conventional variance estimators, and (c) parametric methods and windows of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 years on either side of the cut-off.Footnote 7

The identification of the causal effects of delaying cohabitation on infant mortality relies on four main assumptions. The first is that an effective legal age of marriage of 18 years results in an increase in the mean age at cohabitation. In other words, if the introduction of the RFC did not change the mean age at cohabitation for women at the cut-off, the estimated parameter β1 in Eq. 2 would not be efficient, leading to a problem of weak instruments (Bound et al. 1995). Although the descriptive analysis presented in Section 3 suggests that the rise in the minimum age of marriage led to an increase in the mean age at cohabitation, the existence of a sufficiently sharp change in the mean age at cohabitation and in the incidence of child marriage at the cut-off for the women in the analytical sample is tested empirically in Section 6.1.

The second assumption, which is known in the literature as the exclusion restriction, is that the law only affected differently the probability of infant mortality of the first-born child of women on either side of the cut-off through its effect on the age at first cohabitation. This is, in principle, a plausible assumption because it is difficult to argue that other legal provisions included in the RFC or other policy interventions affected females just above and just below the age 15 differently. Nonetheless, to fully rule out this possibility, I examine in Section 6.3, the discontinuities at the cut-off for a wide range of empowerment and marriage-related outcomes.

The third identification assumption is that the determinants of infant mortality unaffected by the legal change should be continuously related to the forcing variable at the cut-off. Although this condition cannot be tested for every determinant of infant mortality, I examine in Section 6.3 the existence of discontinuities at the cut-off for some variables that might correlate with infant mortality, and that are unlikely to be affected by the legal age of marriage. If the placebo analysis shows discontinuities at the cut-off for these variables, we would need to consider the possibility that confounding factors are driving the results.

Finally, the validity of the RDD estimates also relies on the assumption that women’s ages in the survey were not systematically misreported. My estimates would be compromised if the women who started cohabiting at younger ages had systematically misreported being older, and were therefore exposed to a lower legal age of marriage. I assess and dismiss this hypothesis in Section 6.3 by checking whether there is a discontinuity in the density of the forcing variable at the cut-off.

5 Data and descriptive statistics

The data used in the analysis are from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) conducted in late 2011. The survey collected household-, child-, male-, and female-level information for a sample of 16,702 households that is representative at the national and the regional levels. The women module was applied to all females aged 15–49 living in the households sampled. The DHS includes questions on health, anthropometrics, demographics, fertility, and women’s status within the household. The survey also provides information on the birth and the mortality histories of their children, as well as on the age at first cohabitation, which is used to measure child marriage. On the other hand, the survey provides little information on the respondents’ labor market outcomes, and does not record the age at marriage.Footnote 8 The data on antenatal and postnatal behavior before and after each birth and on children’s health status cover only children who were born in the 5 years prior to the survey, and the share of missing values is large for these children.

The analytical sample is restricted to women living in the regions of Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, SNNP, Tigray, and Amhara; the regions that approved the RFC between 2000 and 2007, and that are used in the analysis. The remaining six Ethiopian regions were excluded from the analytical sample for two reasons. First, five of these regions did not implement the increase in the legal age of marriage before 2008. Thus, even if the RFC had been approved in these regions before 2011, the women in these regions who were aged 15 or younger when the RFC was approved would have been underage at the time of the survey, and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Second, the region of Oromia was excluded from the analysis because even though the regional government of Oromia approved the RFC before 2008, it did not seem to enforce it in any way. The lack of enforcement in this region is evident in Figs. 13 and 14 in the Appendix, which show that in Oromia, the distribution of the age at cohabitation did not change for cohorts exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18, and that the jump at the cut-off—if any—had the opposite sign than the one that was expected. Nonetheless, I test the robustness of the results to the inclusion of this region in the analytical sample in Appendix Appendix and find results consistent with those obtained using the main analytical sample. So, why this region is excluded in the main analysis? While the reasons for the lack of enforcement in Oromia were not investigated in this study, including this region in the analysis reduces the statistical significance of the first-stage regression, which could lead to a problem of weak instruments (Bound et al. 1995), and casts doubts on the estimation of the effect of delaying cohabitation on infant mortality.Footnote 9 Since the main goal of the paper is not to estimate the effects of the law, but to investigate the causal effect of delaying cohabitation on infant mortality, it seems reasonable to focus the main analysis on those regions in which the introduction of the law led to an increase in the age at cohabitation at the cut-off, while then reporting in the Appendix consistent results when the region of Oromia is included in the analysis.

The female module was applied to 8,685 women living in our regions of interest. Out of this sample, I include in the analysis the subsample of 5,078 women who were aged 18–49 at the time of the survey, who ever cohabited with a partner, and who gave birth to their first child at least 12 months before the survey.Footnote 10Footnote 11 My decision to limit the sample to women who had ever cohabited and who had at least one child was motivated by the research question addressed, that is, the estimation of the effect of delaying cohabitation on the probability of infant mortality of the first child. It should be noted that, because of the way the analytical sample is constructed, the mean age at cohabitation is much lower and the prevalence of child marriage is much higher among the youngest girls in the sample. For example, females aged 18 and 19 at the time of the survey were only included in the sample if they had ever cohabited with a partner and had given birth to their first child more than a year ago. The prevalence of child marriage among these girls was, by construction, very close to 100%. It should also be noted, however, that this does not affect the estimates of the analysis, since the effect of the age when the RFC was approved on the age at cohabitation that is caused by the way the sample is constructed changes smoothly at the cut-off.

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics for the main variables used in the analysisfor this sample of 5,078 women. However, it is important to keep in mind that the regression discontinuity analysis does not use all these women to estimate the parameters of interest, but only those who fall within the bandwidth used in the non-parametric analysis or the relevant window in the parametric analysis. Thus, to better illustrate the characteristics of the estimation sample, the table also includes descriptive statistics for the women who fall within the optimal bandwidth used in the preferred specification reported in Columns 5 and 6 of Table 2.

The table shows that the ages in 2011 of the women in the estimation sample ranged from 18 (in Tigray) to 29 (in Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa). The average number of years of education among these women was very low (less than three), which suggest that most of them were no longer attending school when they started cohabiting with a partner. More than 30% of these women were participating in the labor market, and 65% were living in rural areas. Interestingly, 13% of the women in the estimation sample had separated or divorced from their first cohabiting partner. The mean age at cohabitation for these women was slightly higher than 16 years, and more than 65% of them first cohabited with their partner before they turned 18. The mean age of these women at first birth is 18.3 years and the infant mortality rate for their first-born child is 8%. In Table 9 of the Appendix, I provide descriptive statistics for the women who were aged 14-15 when the legal age of marriage was raised in their region. Because the RDD estimates are local in the sense that they are interpreted as the effects for the women who were approximately 15 when the RFC was approved in their region, Table 9 provides descriptive statistics for those women for which the effects are estimated.

Figure 3 displays the statistical association between a woman’s age at cohabitation, her age at first birth, and the probability of infant mortality for her first-born child. The curves are estimated using locally weighted regressions for the sample of women aged 13–17 at the time of the RFC. Although these relationships should not be interpreted as causal, the figure shows a strong correlation between age at first birth and infant mortality during puberty. The graph suggests that delaying the age at first birth from 15 to 17 is associated with a decrease in the incidence of infant mortality for the first-born child from approximately 13.5 to 7.5%. On the other hand, increases in the age at first birth after the age of 18 are associated with smaller reductions in the probability of her first-born child dying during infancy. Although the slope of the estimated function that displays the statistical association between a woman’s age at cohabitation and the probability of infant mortality for her first-born child is less pronounced, the negative statistical association between these two variables is also evident in the graph.

Age at cohabitation, age at birth, and infant mortality of the first-born (locally weighted regressions). Note: These locally weighted regressions displayed in the figure are constructed using the sample of women in the 2011 Ethiopian DHS that are at least 18 years old at the time of the survey and lived in one of the five Ethiopian regions that are included in the analysis

6 Results

6.1 First stage

The first condition for the validity of my identification strategy is the existence of a discrete change in the mean age at first cohabitation at the cut-off. In other words, the women who were exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18 should have started cohabiting significantly later than those who had the opportunity to marry at the age of 15 for a few months before the new law raised the legal age of marriage. The size and the statistical significance of this discontinuity is yielded by the parameter α1 in the first-stage equation. Columns 1, 3, and 5 of Table 2 report the estimates for this parameter using non-parametric techniques with different estimation procedures and bandwidths. The results of the preferred estimation are reported in column 5, and show that exposure to a legal age of marriage of 18 increases a woman’s age at cohabitation by approximately 2 years in the regions included in the sample. When alternative bandwidths and non-parametric estimation procedures are used, the coefficients of the variable are also positive, and are, in most cases, similar in magnitude. The coefficients measuring the effect of exposure to a legal age of marriage of 18 across the different non-parametric estimations are all statistically significant at the 1% and satisfy the relevance condition (F> 10) required for the estimation of the second-stage equation. Table 8 in the Appendix also shows that the results are robust to the use of parametric methods with several windows and order polynomials for the forcing variable. The sharp change in the mean age at cohabitation at the cut-off is also evident in Fig. 4 in which a second-order polynomial for the forcing variable is used. Figure 10 in the Appendix shows graphically the results when a first-order polynomial for the running variable and a locally weighted regressions are used, confirming that the discontinuity at the cut-off is not driven by the order of the polynomial function used.

Main analysis: Age at first cohabitation and child marriage at the cut-off. Note: This figure is constructed using a second-order polynomial at each side of the cut-off and the main analytical sample. The latter includes women who were at least 18 years old at the time of the survey and lived in one of the five Ethiopian regions that are included in the analysis, ever cohabited with a partner, and had given birth. Mean size of the bin is 73 observations

The estimates reported in column 1 of Table 3 indicate that the increase in the mean age at cohabitation is accompanied by a decrease of 20 percentage points in the incidence of child marriage at the cut-off. The results of the first-stage equation are in line with the main conclusions of the descriptive analysis conducted in Section 3, which show how the distribution of the age at cohabitation and the prevalence of child marriage change across cohorts of females exposed to a different legal age of marriage.

The evolution of the prevalence of child marriage and the mean age at cohabitation across age cohorts, shown in Fig. 4, merits two additional comments. First, the large discontinuity at the cut-off and the polynomial behavior at the right of the cut-off are consistent with the hypothesis that because women who were slightly over the age of 15 when the RFC was introduced were pushed to get married before the RFC was approved, the introduction of the RFC reduced the mean age at cohabitation for the cohorts of women who were just above age 15 when the RFC was approved. For example, a woman who was slightly older than 15 years when the RFC was approved had the option of legally marrying as soon as she turned 15, but if she had waited a few months and the RFC was approved, she would have been unable to legally marry until she turned 18. The knowledge of this impending change might have pushed females who were aged 15 at the time the RFC was introduced, and who were planning to get married over the next year or two, to marry as soon as they turned 15. This has important implications for the interpretation of the results: the estimates of interest in the first-stage equation cannot be interpreted as the effect of exposure to a legal age of marriage of 18 relative to exposure to a legal age of marriage of 15. Rather, the discontinuity measures the differential effect of the law on females who were aged just above and just below age 15 when the law was introduced. The size of the discontinuity can be also interpreted as the effect of exposure to a legal age of marriage of 18 relative to having the option to legally marry at age 15 for a few months before the new law was approved.

Second, beyond the large discontinuity at the cut-off, Fig. 4 suggests that the prevalence of child marriage was higher among the younger women in the sample, who were exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18. Although we cannot expect to find that child marriage was eradicated among women who were exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18, the finding that the largest incidence of child marriage was among the youngest cohorts of women in the sample is apparently puzzling. This paradox is explained in the previous section: to estimate the effect of delaying cohabitation on infant mortality, the sample used in the analysis only includes women who had ever cohabited with a partner and had given birth to their first child at least 1 year before the survey. Thus, the prevalence of child marriage among the youngest cohorts of women in the sample, who were barely aged 18 at the time of the survey, is expected to be very close to 100%.Footnote 12 The true evolution of the prevalence of child marriage across age cohorts in the five Ethiopian regions of interest is presented in Fig. 2. Using the full sample of women aged 18–49 included in the DHS data, regardless of whether they had ever cohabited with a partner or had given birth, the figure shows that the prevalence of child marriage was lower among the younger cohorts of women, and changed sharply at the cut-off.

6.2 The effect of age at cohabitation on infant mortality

The causal effect of a woman’s age at cohabitation during her teenage years on the probability of her first-born child dying in infancy is yielded by the parameter β1 in the second-stage equation. The results for the non-parametric estimations are reported in columns 2, 4, and 6 of Table 2; and reveal that a 1-year delay in a woman’s age at first cohabitation decreases the probability of infant mortality for her first-born by 3.8–5.2 percentage points, depending on the bandwidth and the estimation procedure used. The most conservative estimation, reported in column 6, indicates that a 1-year delay in a woman’s age at cohabitation decreases the probability of infant mortality for her first-born by 3.8 percentage points. The effect is statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. The results of the parametric analysis using multiple bandwidths and order polynomials for the forcing variable are reported in Table 8 in the Appendix. They show that the effect of delaying cohabitation on infant mortality spotted is not driven by the estimation method, the selection of bandwidth, or the polynomial function used. The discontinuity in the probability of infant mortality among women on either side of the cut-off is also evident in Fig. 5, which uses a second-order polynomial for the forcing variable. Figure 11 in the Appendix shows graphically that the discontinuity at the cut-off remains significant when a first-order polynomial and a non-parametric locally weighted regression for the forcing variable are used.

Main analysis: Infant mortality rate at the cut-off. Note: This figure is constructed using a second-order polynomial at each side of the cut-off and the main analytical sample. The latter includes women who were at least 18 years old at the time of the survey and lived in one of the five Ethiopian regions that are included in the analysis, ever cohabited with a partner, and had given birth. Mean size of the bin is 73 observations

The heterogeneous effects of delaying age at cohabitation on infant mortality in rural and urban areas are examined in Table 11 in the Appendix. The estimates reported in the table indicate that the effect of age at cohabitation on infant mortality seems to be larger in rural areas, suggesting that delaying age at cohabitation might be particularly beneficial for girls and women living in settings with limited access to health facilities. The results of these heterogeneity analyses should nonetheless be interpreted with caution due to lack of statistical power and weak statistical significance of the first stage when the sample is split.

When interpreting the coefficients of the second-stage equation, it is important to consider that the estimated effect of early cohabitation on the probability of infant mortality of the first-born is a local average treatment effect. More specifically, the parameter of interest in the regression measures the effect of a 1-year delay in the age at cohabitation during the teenage years for those women in the sample who were approximately 15 years old when the RFC was approved in their region, and who delayed cohabitation because they were exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18. In other words, the effect of delaying marriage on infant mortality was identified for the subsample of Ethiopian women aged 18 to 25 who ever cohabited with a partner; who gave birth to their first child at least 1 year before the survey; and who either were living in an area where the capacity of the institutions to enforce the law was strong, or were particularly law-abiding.

6.3 Robustness checks

The previous section shows that in the five Ethiopian regions analyzed, exposure to a minimum age of marriage at 18 relative to the possibility of getting legally married at 15 for a few months increases significantly age at cohabitation and this translates into a reduction in the prevalence of infant mortality among the first-born. In this section, I discuss and explore alternative explanations for the results.

First, in addition to raising the legal age of marriage for females, the RFC included some provisions aimed at changing the balance of power within the household by facilitating divorce, abolishing the right of a husband to forbid his wife to work, and extending the right to administer the common marital property to the wife. These legal changes may have improved women’s economic status, empowerment and marriage market outcomes ultimately affecting infant mortality.

Although this is plausible, the broad effects of the RFC would only threaten the identification strategy if these additional provisions had different effects on women who were just below and just above the age of 15 when the RFC was introduced. This is, however, unlikely because all of these norms were applied regardless of whether women were already married, and therefore, should not have affected women on either side of the cut-off differently. To fully rule out this hypothesis, I examined empirically whether the law had different effects on the labor force participation, divorce rates, participation in household decisions, and other marriage market outcomes of women on either side of the cut-off. To measure women’s participation in household decisions, I used a set of questions in the DHS survey that provide information on which family members make the decisions regarding visits to relatives, household purchases, health expenditures, and the administration of the money earned by the husband. Each of these variables took the value of zero if the woman was not participating in these decisions, of one if the woman was co-participating, and of two if the decisions were being made by the woman alone. Then, I constructed a self-reported empowerment index for each woman as an average score in these questions. Using each of these self-reported empowerment measures, labor force participation, the probability of divorce, and other marriage market outcomes as dependent variables, I estimated the following regression:

The results of this analysis, reported in Table 3, suggest that the dispositions included in the RFC aimed at changing the balance of power within the household did not have different effects on labor force participation, divorce rates, and participation in household decisions of women on either side of the cut-off. Furthermore, the lack of discontinuities at the cut-off in terms of the partner’s characteristics, such as the age difference between the partners, partner’s years of education, and partner’s labor market outcomes, rule out the possibility that the additional legal provisions could have driven the results on infant mortality by allowing females who were younger than 15 to marry better husbands. Thus, the results of the analysis confirm that the effect on infant mortality identified in the study was not driven by these additional norms aimed at increasing women’s bargaining power within the household.

Second, I examined the existence of discontinuities in variables that were likely unaffected by the reform, including the ethnicity and religion of the women and the gender of their first-born child. This is an indirect empirical test for the third identification assumption discussed in Section 4: the determinants of infant mortality unaffected by the reform should change smoothly at the cut-off. In order to test this hypothesis, I estimated (1) and (2) using the bias-corrected RD estimates with a robust variance estimator and an optimal bandwidth calculated following Calonico et al. (2014); and using whether the first-born was male and whether the mother was Orthodox or was from the Oromo ethnic group as outcome variables.Footnote 13 The results of these estimations are provided in columns 1 to 6 of Table 4. The coefficients in the second-stage regressions are small and largely insignificant, which confirms that there is not any discontinuity in these placebo variables at the cut-off. The absence of discontinuities at the cut-off for these placebo variables is also evident in Fig. 6. I test further the hypothesis that women at both sides of the discontinuity are comparable in Table 10 in the Appendix, where I show that the mean value of these placebo variables do not differ for the sample of women that were aged 15 when the RFC was introduced in their region and for the sample of women that were aged 14 at the same time.

Placebo variables: ethnicity, religion, and gender. Note: This figure is constructed using a second-order polynomial at each side of the cut-off and the main analytical sample. The latter includes women who were at least 18 years old at the time of the survey and lived in one of the five Ethiopian regions that are included in the analysis, ever cohabited with a partner, and had given birth. Mean size of the bin is 90 observations

Third, I examined whether the difference in the infant mortality rates of the first-born among women on either side of the cut-off could have been driven by systematic differences between women born in different months of the year, rather than by exposure to a different legal age of marriage. To assess this possibility, I re-estimated (1) and (2) setting a placebo cut-off for women older than age 19, rather than 15, when the RFC was approved. This exercise is equivalent to setting the cut-off as if the law had been introduced exactly 4 years before the real date of approval (e.g., July 4, 1996, for Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa). If the results of the study on infant mortality were driven by systematic differences between women born in different months, we would expect to find a discontinuity in the infant mortality rate of the first-born among women born in different months every year. The results of this placebo test are reported in columns 7 and 8 of Table 4, and show no discontinuities for the mean age at cohabitation or the infant mortality rate at the false cut-off. This finding suggests that the main conclusions are not driven by systematic differences between women born in different months of the year. The exercise is repeated setting the placebo cut-off for women aged 16, 17, and 18 when the RFC was approved with similar results.Footnote 14

Fourth, one may argue that the discontinuity found in the first stage might capture an odd time trend or the effect of other national- or regional-level policies. One example of a national-level policy was the introduction of the Health Expansion Program (HEP), launched in 2003. In order to confound the results of our RDD analysis, the HEP or any other intervention should have had different effects on the women who were just above and just below 15 years old when the RFC was introduced. To explore further this possibility, I re-estimated the results using the Ethiopian regions of Afar, Harari, Gambella, Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz, and falsely set the approval date of the RFC in these placebo regions in July 2000.Footnote 15 I restricted the analysis to these five regions because none of them passed the RFC before 2008, which means that the women in the sample (who were older than 18 at the time of the survey) were unaffected by the increase in the legal age of marriage in these regions. The results of this placebo test are reported in columns 9 and 10 of Table 4. They show no significant discontinuity in the mean age at cohabitation or in the infant mortality rate at the cut-off in those regions that did not approve the RFC before 2008. While the second stage estimates should be interpreted with caution due to the irrelevance of the first stage, these results diminish the concern that the effect was driven by a national-level policy that affected differently women on either side of the cut-off.Footnote 16 As an additional check, I conducted the same analysis but falsely setting the approval date of the RFC in September 2003, the starting date of the HEP program. The results, reported in Table 14 in the Appendix, show no discontinuities at the cut-off neither on regions where the RFC was introduced before 2008 nor in non-RFC regions.

Fifth, if postponement of cohabitation resulted in a postponement of parenthood, the women who were slightly younger than 15 when the RFC was approved ended up having their first child significantly later than women who were aged slightly above 15 when the RFC was introduced. In this context, it is possible that the parameter β1 in (2) was capturing over-time reductions in infant mortality that were unrelated to the age at first cohabitation. I investigated this possibility by re-estimating (1) and (2), including the year of birth of the first-born as a control variable. This variable was included to account for secular time trends in infant mortality.Footnote 17 The estimates provided in columns 10 and 11 show that the direction and the significance of the parameters estimated in the main analysis (reported in Table 2) did not vary when the year of birth of the first child was included in the regression. The latter finding suggests that the reduction in the probability of infant mortality of the first-born at the cut-off was not driven by a secular trend in infant mortality.

Sixth, the main results of the study were also found to be robust to restricting the analysis to the subsample of women who were still living with their first partner at the time of the survey. The results of this robustness check are reported in columns 1 to 4 of Table 5, and they are consistent with those obtained when using the main sample.

Another threat to the interpretation of the estimates could be the possible existence of selective migration. In other words, the women who were under age 15 when the legal age of marriage was raised in their region and who were particularly interested in early cohabitation could have migrated to regions where the legal age of marriage was not raised. If the share of females migrating for this reason was substantial, the results might be biased by selective attrition at one side of the cut-off. Although the lack of information on women’s region of origin hindered the assessment of this hypothesis in our data, the lack of discontinuity in the density of the forcing variable at the cut-off, which can be seen in Fig. 18 in the Appendix, suggests that the migration of women who were slightly younger than 15 when the RFC was approved was not a widespread phenomenon. In line with the lack of inter-regional migration in response to the law, Bundervoet (2018) reveals that internal migration is very low in Ethiopia and, with the exception of Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa, occurred mainly within regional borders. Furthermore, the fact that the incidence of child marriage was above 10% in every Ethiopian region, even among the women who were exposed to a legal age of marriage of 18, may indicate that the women (or their families) who were interested in cohabiting before the age of 18 did not need to migrate to another region to do so.

Additionally, the possibility that women manipulated their reported age in the survey (the base for the construction of the forcing variable) was examined by conducting a McCrary test. The results of the McCrary test, which are graphically displayed in Fig. 18 in the Appendix, show that the density of the forcing variable does not change significantly at the cut-off. This finding suggests that women who were just below or just above the cut-off age did not systematically misreport their age in the survey, which is the fourth identification condition described in Section 4. Furthermore, the potential bias induced by measurement error in the reported age at cohabitation in the second-stage equation is addressed through the use of the woman’s age when the RFC was approved as an instrumental variable in the regression.

I also explored the robustness of the results to alternative definitions of the dependent variable. To do so, I re-estimated (1) and (2) for alternative measures of early mortality. The estimates, reported in Fig. 19 in the Appendix, reveal that the effect of a 1-year delay in a woman’s age at cohabitation during her teenage years on the probability of her first-born child dying within the first 2 months of life was very similar to the effect on her first-born child dying within the first 12 months of life. More broadly, the evidence confirms that the results of the study are robust to the definition of the dependent variable, and suggests that most of the effect of child marriage on the mortality of the first-born occurs during the very early months of the newborn’s life.

Finally, I conduct additional robustness checks in the Appendix including the use of a difference-in-differences strategy, the re-estimation of the main results of the paper using a common bandwidth, and the robustness of the results to the inclusion of Oromo region in the main analysis, which is the region in which the RFC was introduced before 2008 but not enforced. The results of these tests are largely consistent with those reported in the previous section.

7 Mechanisms

One potential mechanism driving the effect of a woman’s early cohabitation on the probability of infant mortality for her first-born child was her age at first birth. Figure 3 shows the strong negative association in the Ethiopian data between age at first birth and infant mortality for girls in their early teenage years. Among the possible explanations for this negative association—which has been well-documented in the medical literature—is that the body of a teenage woman is still not optimal for the development of a successful pregnancy, and/or that the mother’s lack of psychological maturity can result in inadequate antenatal and postnatal health behaviors (Chen et al. 2007; Olausson et al. 1999).

To examine this mechanism, I re-estimated (1) and (2) using fertility outcomes, and antenatal and postnatal behaviors as dependent variables in the second-stage equations.

The results on age at first birth are displayed in columns 1 and 2 of Table 6, and confirm that although the coefficient is lower than 1, delaying cohabitation causally increases the age of women at first birth. In line with this age at birth mechanism, the estimates reported in columns 5 and 6 suggest that the effect of age at cohabitation on infant mortality vanishes for children born after the first child.

On the other hand, the effect of age at cohabitation on the adoption of antenatal and postnatal health practices is statistically indistinguishable from 0 at conventional significance levels. The coefficient measuring the effect of age at cohabitation on the number of vaccines given to the children has the expected positive sign, although the magnitude is small and statistically insignificant. Similarly, the coefficients for antenatal visits, months of breastfeeding, and birth at home in the second-stage equations are statistically insignificant at conventional confidence levels. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the results on the adoption of antenatal and postnatal health behaviors should be interpreted as suggestive only, because the DHS data only report information on these variables if the first-born was alive and was born less than 5 years prior to the survey. This could be problematic, both because the sample size used in the analysis is much smaller, which reduces the statistical power of the estimations, and because the limitations in the data collection may induce a problem of sample selection bias. Indeed, using this limited subsample of children, I did not find any significant effect of delaying cohabitation on measures of child health such as birth weight or the prevalence of anemia (results reported in columns 28 and 36 of Table 6).

However, a woman’s age at cohabitation could have also affected infant mortality through other paths. For example, if a woman is very young when she starts cohabiting, her levels of participation in household decisions might be low (Jensen and Thornton 2003). Since women and men tend to have different preferences for investing in children’s health (Allendorf 2007; Majlesi 2014), women’s early cohabitation may lead to higher infant mortality rates. Similarly, when a woman is very young when she starts cohabiting, her ability to invest in her children’s health may be constrained by her educational attainment (Field and Ambrus 2008) and labor market outcomes (Elborgh-Woytek et al. 2013). On the other hand, given the premium on early marriage in the marriage market (Wahhaj 2018), it is also possible that early marriage reduces infant mortality by improving women’s marriage market outcomes.

To investigate these paths of impact, I estimate the effect of early cohabitation on women’s participation in household decisions, marriage market outcomes, labor force participation, health, and educational attainment. The results of the estimates for Eqs. 1 and 2 using these outcomes as dependent variables are reported in columns 7 to 24 of Table 6. The results confirm that, in our sample, delaying age at cohabitation does not seem to affect women’s labor force participation, health, education, participation in household decisions, and marriage market outcomes, including the age difference with the partner, the wealth index, partner’s years of education, and partner’s labor market outcomes.

Placebo test: Discontinuity in other Ethiopian regions. Note: This figure is constructed using a second-order polynomial at each side of the cut-off. The analysis is set for those regions that did not approve the Revised Family Code before 2008 (Somali, Afar, Gambella, Benishangul-Gumuz, and Harari), and the cut-off is set as if the law was approved in these regions in July 2000. Mean size of the bin is 80 observations

Taken together, these results suggest that the effect on infant mortality of a woman delaying her age at cohabitation during her teenage years operates mainly through an increase in her age at first birth. On the other hand, and given the data limitations, I cannot rule out the possibility that the effect is also channeled through higher levels of antenatal and postnatal investments by females who start cohabiting later. However, given the lack of effect of the age at cohabitation on self-reported empowerment, labor market outcomes, or education, any potential effect of the age at cohabitation on infant mortality via antenatal and postnatal investments would probably be linked to an older age at first birth and more mature behavior.

8 Conclusions

This study makes three contributions. First, it adds to the thin body of evidence that investigate the effects of child marriage through assessing the causal effect of child marriage on infant mortality in Ethiopia. Second, the results of the study suggest that laws that raise the legal age of marriage can contribute to reducing child marriage, even in contexts where the capacity to enforce the law is limited. Finally, the study provides an alternative identification strategy that can be used to expand the analysis of the causal effects of child marriage to other outcomes and settings where similar laws have been approved.

Using a fuzzy RDD that exploits age discontinuities in exposure to a law that raised the legal age of marriage for Ethiopian females, the study estimates that a 1-year delay in a woman’s age at cohabitation during her teenage years reduces the probability of infant mortality for her first-born child by 3.8 percentage points (mean 10%). The size of this effect is comparable to the joint effect on child mortality at the village level of moving from 0% coverage of measles, BCG, DPT, polio, and maternal tetanus vaccinations to 100% coverage (McGovern and Canning 2015).Footnote 18

The results of the analysis of mechanisms suggest that the strong impact of early cohabitation on the probability of infant mortality seems to be driven by the positive effect of delaying cohabitation on age at first birth. However, due to data limitations, it is not possible to disentangle whether this age at birth effect is caused by purely biological factors or by more mature behavior, which may be associated with the adoption of antenatal and postnatal health measures. On the other hand, the analysis rules out the possibility that the effect of early cohabitation on infant mortality is driven by an effect of the former on her marriage market outcomes, participation in household decisions, education, or labor force participation. The causal link between child marriage, age at birth, and infant mortality spotted in this study is consistent with existing evidence from previous studies that use correlation analysis to explore the link between these variables. For example, Raj et al. (2010) found an odds ratio of 1.5, significant at the 95%, for the statistical association between infant mortality and women who marry before the age of 18 in India. Similarly, using household data from Nepal, Adhikari (2003) showed that the neonatal mortality rates among the children of mothers aged 15–19 are 73% higher than the corresponding rates among the children of mothers aged 20–29.

Although the effects on infant mortality found in the study are large, it is important to acknowledge that the estimates yielded by the RDD employed are local, and that any generalization of these results to the whole Ethiopian female population or to non-first-born infants should therefore be avoided. First, the RDD approach only identifies effects for those women at the cut-off. In our case, these were women who were aged 18 to 26 years old at the time of the survey, who had ever cohabited with a partner, and who gave birth to their first child at least 1 year before the survey. Second, the causal effect of delaying cohabitation on infant mortality is only identified for the compliers. These are women who postponed their age at cohabitation because they were exposed to a different legal age of marriage (Angrist and Pischke 2008). It is likely that these women either were law-abiding or were living in areas where the presence of the state was strong. Third, the analysis did not find any effect of early cohabitation on the infant mortality rates of children born after the first child, which is consistent with the age at birth mechanism.

Notes

UNICEF defines child marriage as a formal marriage or an unmarried cohabitation in which one or both of the partners are under 18 years of age. Although child marriage affects both girls and boys, 82% of children across the globe who married or started cohabiting with a partner before the age of 18 are girls (UNICEF 2014).

The CEDAW is the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, ratified in 1979. The CCMMAMRM is the Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage, and Registration of Marriage, ratified in 1964. The Maputo Protocol was ratified in 2003.

Girls not Brides website. http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/where-does-it-happen/

Although underage marriage was not permitted in the RFC, the criminal code did not sanction it until 2005. Unlike the introduction of the law in the 5 regions used in the sample, the introduction of child marriage as an offense in the criminal law did not generate a sharp change in the mean age at cohabitation in these regions. Therefore, this reform in the criminal code is not used for identification purposes.

The possible causes for this are discussed in Section 3.

The age of the women who were approximately age 15 when the RFC was approved in their region at the time of the 2011 survey ranges from 18 in Tigray to 26 in Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa.

For the non-parametric analysis, I follow Calonico et al. (2014, 2016) and estimate the results using three different procedures: (1) conventional RD estimates with a conventional variance estimator, (2) bias-corrected RD estimates with a conventional variance estimator, and the preferred approach (3) bias-corrected RD estimates with a robust variance estimator. The conventional estimates are conducted using local linear regressions, and the bias-corrected estimates are conducted using local quadratic regressions, which result on different bandwidths. The robust variance estimator results in more conservative standard errors for the estimates of interest than conventional variance estimator. Further technical details about these three standard procedures are provided in Calonico et al. (2014, 2016). For the parametric analysis, I follow Gelman and Imbens (2019), who discouraged the use of polynomials of order three and above in parametric RDDs, and include polynomials of orders one and two for the forcing variable, while also allowing for a different polynomial function on either side of the cut-off.

Unmarried cohabitation is strongly stigmatized in Ethiopia and is infrequent among most ethnic groups (Jones et al. 2016). Furthermore, even if the age at cohabitation and the age at marriage were different, it seems reasonable to assume that the former is a more relevant determinant of infant mortality and a woman’s well-being.

One potential reason could be that the capacity or the willingness to enforce the law in this region is weak or that there is more resistance to the law from the citizens.

Of the women in these regions who gave birth to at least one child, 1.31% reported that they had never cohabited with a partner. These observations are not used in the analysis.

Because infant mortality is defined as mortality within the first year of life, the sample is restricted to those women who gave birth to their first child more than 1 year before the survey to avoid censoring in the dependent variable.

The effect of distance to the threshold on child marriage, age at cohabitation and infant mortality that is mechanically driven by the way the sample is constructed does not affect the RDD estimates since this mechanic effect changes smoothly at the cut-off.

Ethiopian Orthodox is the most prevalent religion in Ethiopia. Oromo is the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia.

My decision to set the placebo cut-off at 19 years was driven by the convenience of setting the false cut-off at a value of the forcing variable that left out of the estimation the observations around the real cut-off. Nonetheless, I have also conducted the analysis setting the placebo cut-off for women aged 16, 17, and 18 when the RFC was approved. This exercise was equivalent to setting the cut-off as if the law had been introduced exactly 1, 2, and 3 years before the real date of approval. The results of these placebo analyses consistently show no statistically significant discontinuities in infant mortality and age at cohabitation at the false cut-offs when the bandwidth was set to drop from the estimation the observations around the real cut-off.

On July 4, 2000, the Federal Government of Ethiopia approved the RFC, and the law went into effect in Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa.

I searched background information for other national or regional programs that could be affecting differently the age at cohabitation or infant mortality of women that were just below and above 15 when the RFC was introduced and did not find any other policy that could be confounding the results.

The year of birth of the first-born is not included as control variable in the main results reported in Section 6 because the year of birth could have been the result of a fertility decision made by the mother, and might therefore have been affected by the age at cohabitation. Thus, including it in the main regression could lead to a bad control problem (Angrist and Pischke 2008).

Using DHS data from 62 countries,McGovern and Canning (2015) estimated at 0.73 the relative risk of child mortality at the village level associated with moving from 0% coverage of measles, BCG, DPT, polio, and maternal tetanus vaccinations to 100% coverage. At the cut-off, the relative risk of the infant mortality of the first-born associated with a 1-year increase in the age at cohabitation is estimated at 0.75.

References

Adhikari R (2003) Early marriage and childbearing: risks and consequences. In: Bott S, Jejeebhoy S, Shah I, Puri C (eds) Towards adulthood: exploring the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents in South Asia. World Health Organization, pp 62–66

Allendorf K (2007) Do women’s land rights promote empowerment and child health in Nepal? World Dev 35(11):1975–1988

Angrist JD, Pischke J-S (2008) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Asadullah M, Wahhaj Z (2018) Early marriage, social networks and the transmission of norms. Economica

Asadullah N, Alim A, Khatoon F, Chaudhury N (2016) Maternal early marriage and cognitive skills development: an intergenerational analysis. Technical report, Unpublished working paper

Bandiera O, Buehren N, Burgess R, Goldstein M, Gulesci S, Rasul I, Sulaiman M (2018) Women’s empowerment in action: evidence from a randomized control trial in Africa. Technical report, CEPR Discussion Papers 13386

Belles-Obrero C, Lombardi M (2020) Will you marry me, later? age-of-marriage laws and child marriage in Mexico. J Human Resour 14

Blackburn ML, Bloom DE, Neumark D (1993) Fertility timing, wages, and human capital. J Popul Econ 6(1):1–30

Bound J, Jaeger DA, Baker RM (1995) Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogeneous explanatory variable is weak. J Am Stat Assoc 90(430):443–450

Bundervoet T (2018) Internal migration in Ethiopia: evidence from quantitative and qualitative research study. Technical report, World Bank

Calonico S, Cattaneo MD, Farrell M, Titiunik R (2016) Regression discontinuity designs using covariates. Technical report, University of Michigan

Calonico S, Cattaneo MD, Titiunik R (2014) Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression discontinuity designs. Econometrica 82:2295–2326

Campbell J (2002) Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 359(9314):1331–1336

Chari A, Heath R, Maertens A, Fatima F (2017) The causal effect of maternal age at marriage on child wellbeing: evidence from India. J Dev Econ 127:42–55

Chen X-K, Wen SW, Fleming N, Demissie K, Rhoads G, Walker M (2007) Teenage pregnancies and adverse birth outcomes: a large population based retrospective study. Int J Epidemiol 36(2):368–373