Abstract

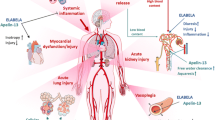

Catecholamines are endogenous neurosignalling mediators and hormones. They are integral in maintaining homeostasis by promptly responding to any stressor. Their synthetic equivalents are the current mainstay of treatment in shock states to counteract myocardial depression and/or vasoplegia. These phenomena are related in large part to decreased adrenoreceptor sensitivity and altered adrenergic signalling, with resultant vascular and cardiomyocyte hyporeactivity. Catecholamines are predominantly used in supraphysiological doses to overcome these pathological consequences. However, these adrenergic agents cause direct organ damage and have multiple ‘off-target’ biological effects on immune, metabolic and coagulation pathways, most of which are not monitored or recognised at the bedside. Such detrimental consequences may contribute negatively to patient outcomes. This review explores the schizophrenic ‘Jekyll-and-Hyde’ characteristics of catecholamines in critical illness, as they are both necessary for survival yet detrimental in excess. This article covers catecholamine physiology, the pleiotropic effects of catecholamines on various body systems and pathways, and potential alternatives for haemodynamic support and adrenergic modulation in the critically ill.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Beutler B, Hoebe K, Du X et al (2003) How we detect microbes and respond to them: the Toll-like receptors and their transducers. J Leukoc Biol 74:479–485

Tang D, Kang R, Coyne CB et al (2012) PAMPs and DAMPs: signals that spur autophagy and immunity. Immunol Rev 249:158–175

Shi Y, Evans JE, Rock KL (2003) Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature 425:516–521

Abraham E, Singer M (2007) Mechanisms of sepsis-induced organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med 35:2408–2416

Spronk PE, Zandstra DF, Ince C (2004) Bench-to-bedside review: sepsis is a disease of the microcirculation. Crit Care 8:462–468

Brealey D, Brand M, Hargreaves I et al (2002) Association between mitochondrial dysfunction and severity and outcome of septic shock. Lancet 360:219–223

Hochachka PW, Buck LT, Doll CJ et al (1996) Unifying theory of hypoxia tolerance: molecular/metabolic defense and rescue mechanisms for surviving oxygen lack. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:9493–9498

Rudiger A, Singer M (2007) Mechanisms of sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction. Crit Care Med 35:1599–1608

Landesberg G, Gilon D, Meroz Y et al (2012) Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. Eur Heart J 33:895–903

Spies C, Haude V, Fitzner R et al (1998) Serum cardiac troponin T as a prognostic marker in early sepsis. Chest 113:1055–1063

Maeder M, Fehr T, Rickli H, Ammann P (2006) Sepsis-associated myocardial dysfunction: diagnostic and prognostic impact of cardiac troponins and natriuretic peptides. Chest 129:1349–1366

Parker MM, Shelhamer JH, Bacharach SL et al (1984) Profound but reversible myocardial depression in patients with septic shock. Ann Intern Med 100:483–490

Kimmoun A, Ducroq N, Levy B (2013) Mechanisms of vascular hyporesponsiveness in septic shock. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 11:139–149

Landry DW, Levin HR, Gallant EM et al (1997) Vasopressin deficiency contributes to the vasodilation of septic shock. Circulation 95:1122–1125

Bucher M, Ittner KP, Hobbhahn J et al (2001) Downregulation of angiotensin II type 1 receptors during sepsis. Hypertension 38:177–182

Woolf PD, Hamill RW, Lee LA et al (1988) Free and total catecholamines in critical illness. Am J Physiol 254:E287–E291

Lin IY, Ma HP, Lin AC et al (2005) Low plasma vasopressin/norepinephrine ratio predicts septic shock. Am J Emerg Med 23:718–724

Chrousos GP (2009) Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat Rev Endocrinol 5:374–381

Krasel C, Vilardaga JP, Bünemann M et al (2004) Kinetics of G-protein-coupled receptor signalling and desensitization. Biochem Soc Trans 32:1029–1031

Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD (2003) The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Rev 42:33–84

Perlman RL, Chalfie M (1977) Catecholamine release from the adrenal medulla. Clin Endocrinol Metab 6:551–576

Schaper J, Meiser E, Stämmler G (1985) Ultrastructural morphometric analysis of myocardium from dogs, rats, hamsters, mice, and from human hearts. Circ Res 56:377–391

Ellison GM, Torella D, Karakikes I et al (2007) Acute beta-adrenergic overload produces myocyte damage through calcium leakage from the ryanodine receptor 2 but spares cardiac stem cells. J Biol Chem 282:11397–11409

Karch SB (1987) Resuscitation-induced myocardial necrosis. Catecholamines and defibrillation. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 8:3–8

De Jonge WJ (2013) The gut’s little brain in control of intestinal immunity. ISRN Gastroenterol 2013:630159

Yang S, Koo DJ, Zhou M, Chaudry IH et al (2000) Gut-derived norepinephrine plays a critical role in producing hepatocellular dysfunction during early sepsis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279:G1274–G1281

Zhou M, Das P, Simms HH, Wang P (2005) Gut-derived norepinephrine plays an important role in up-regulating IL-1beta and IL-10. Biochim Biophys Acta 1740:446–452

Yang S, Zhou M, Chaudry IH, Wang P (2001) Norepinephrine-induced hepatocellular dysfunction in early sepsis is mediated by activation of alpha2-adrenoceptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281:G1014–G1021

Adeva-Andany M, López-Ojén M, Funcasta-Calderón R et al (2014) Comprehensive review on lactate metabolism in human health. Mitochondrion 17:76–100

Von Känel R, Dimsdale JE (2000) Effects of sympathetic activation by adrenergic infusions on hemostasis in vivo. Eur J Haematol 65:357–369

Mignini F, Streccioni V, Amenta F (2003) Autonomic innervation of immune organs and neuroimmune modulation. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol 23:1–25

Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Nadeau BA, Chen AJ et al (2007) Phagocyte-derived catecholamines enhance acute inflammatory injury. Nature 449:721–725

Sternberg EM (2006) Neural regulation of innate immunity: a coordinated nonspecific host response to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 6:318–328

Wenisch C, Parschalk B, Weiss A et al (1996) High-dose catecholamine treatment decreases polymorphonuclear leukocyte phagocytic capacity and reactive oxygen production. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 3:423–428

Kohm AP, Sanders VM (2001) Norepinephrine and beta 2-adrenergic receptor stimulation regulate CD4+ T and B lymphocyte function in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol Rev 53:487–525

Huang HW, Tang JL, Han XH et al (2013) Lymphocyte-derived catecholamines induce a shift of Th1/Th2 balance toward Th2 polarization. Neuroimmunomodulation 20:1–8

Lyte M, Freestone PP, Neal CP et al (2003) Stimulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis growth and biofilm formation by catecholamine inotropes. Lancet 361:130–135

Freestone PP, Haigh RD, Lyte M (2007) Specificity of catecholamine-induced growth in Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica and Yersinia enterocolitica. FEMS Microbiol Lett 269:221–228

Freestone PP, Hirst RA, Sandrini SM et al (2012) Pseudomonas aeruginosa–catecholamine inotrope interactions: a contributory factor in the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia? Chest 142:1200–1210

Messenger AJ, Barclay R (1983) Bacteria, iron and pathogenicity. Biochem Educ 11:54–62

Sandrini S, Alghofaili F, Freestone PP et al (2014) Host stress hormone norepinephrine stimulates pneumococcal growth, biofilm formation and virulence gene expression. BMC Microbiol 14:180

Freestone PP, Haigh RD, Lyte M (2008) Catecholamine inotrope resuscitation of antibiotic-damaged staphylococci and its blockade by specific receptor antagonists. J Infect Dis 197:1044–1052

Karavolos MH, Winzer K, Williams P et al (2013) Pathogen espionage: multiple bacterial adrenergic sensors eavesdrop on host communication systems. Mol Microbiol 87:455–465

Cogan TA, Thomas AO, Rees LE et al (2007) Norepinephrine increases the pathogenic potential of Campylobacter jejuni. Gut 56:1060–1065

Prass K, Meisel C, Hoflich C et al (2003) Stroke-induced immunodeficiency promotes spontaneous bacterial infections and is mediated by sympathetic activation reversal by poststroke T helper cell type 1-like immunostimulation. J Exp Med 198:725–736

Chamorro A, Urra X, Planas AM (2007) Infection after acute ischemic stroke: a manifestation of brain-induced immunodepression. Stroke 38:1097–1103

Chamorro A, Amaro S, Vargas M et al (2007) Catecholamines, infection, and death in acute ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci 252:29–35

Wu HP, Chung K, Lin CY, Jiang BY et al (2013) Associations of T helper 1, 2, 17 and regulatory T lymphocytes with mortality in severe sepsis. Inflamm Res 62:751–763

Rizza RA, Cryer PE, Haymond MW et al (1980) Adrenergic mechanisms of catecholamine action on glucose homeostasis in man. Metabolism 29:1155–1163

Savary S, Trompier D, Andréoletti P, Le Borgne F et al (2012) Fatty acids - induced lipotoxicity and inflammation. Curr Drug Metab 13:1358–1370

Kjekshus JK, Mjos OD (1972) Effect of free fatty acids on myocardial function and metabolism in the ischemic dog heart. J Clin Invest 51:1767–1776

Treggiari MM, Romand JA, Burgener D et al (2002) Effect of increasing norepinephrine dosage on regional blood flow in a porcine model of endotoxin shock. Crit Care Med 30:1334–1339

Martikainen TJ, Tenhunen JJ, Giovannini I et al (2005) Epinephrine induces tissue perfusion deficit in porcine endotoxin shock: evaluation by regional CO2 content gradients and lactate-to-pyruvate ratios. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 288:G586–G592

Coopersmith CM, Stromberg PE, Davis CG et al (2003) Sepsis from Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia decreases intestinal proliferation and induces gut epithelial cell cycle arrest. Crit Care Med 31:1630–1637

Vlisidou I, Lyte M, van Diemen PM et al (2004) The neuroendocrine stress hormone norepinephrine augments Escherichia coli O157:H7-induced enteritis and adherence in a bovine ligated ileal loop model of infection. Infect Immun 72:5446–5451

Chen C, Lyte M, Stevens MP, Vulchanova L et al (2006) Mucosally-directed adrenergic nerves and sympathomimetic drugs enhance non-intimate adherence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to porcine cecum and colon. Eur J Pharmacol 539:116–124

Green BT, Lyte M, Kulkarni-Narla A et al (2003) Neuromodulation of enteropathogen internalization in Peyer’s patches from porcine jejunum. J Neuroimmunol 141:74–82

Whitelaw BC, Prague JK, Mustafa OG et al (2014) Phaeochromocytoma crisis. Clin Endocrinol 80:13–22

Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA et al (2005) Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med 352:539–548

Guglin M, Novotorova I (2011) Neurogenic stunned myocardium and takotsubo cardiomyopathy are the same syndrome: a pooled analysis. Congest Heart Fail 17:127–132

Ostrowski SR, Pedersen SH, Jensen JS et al (2013) Acute myocardial infarction is associated with endothelial glycocalyx and cell damage and a parallel increase in circulating catecholamines. Crit Care 17:R32

Venugopalan P, Argawal AK (2003) Plasma catecholamine levels parallel severity of heart failure and have prognostic value in children with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail 5:655–658

Tage-Jensen U, Henriksen JH, Christensen E et al (1988) Plasma catecholamine level and portal venous pressure as guides to prognosis in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 6:350–358

Feibel JH, Hardy PM, Campbell RG et al (1977) Prognostic value of the stress response following stroke. JAMA 238:1374–1376

Johansson PI, Stensballe J, Rasmussen LS et al (2012) High circulating adrenaline levels at admission predict increased mortality after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 72:428–436

Ostrowski SR, Gaïni S, Pedersen C et al (2015) Sympathoadrenal activation and endothelial damage in patients with varying degrees of acute infectious disease: an observational study. J Crit Care 2015(30):90–96

Reuben DB, Talvi SLA, Rowe JW et al (2000) High urinary catecholamine excretion predicts mortality and functional decline in high-functioning, community-dwelling older persons: MacArthus Studies of Successful Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 55:M618–M624

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al (2013) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 39:165–228

Myburgh JA, Higgins A, Jovanovska A et al (2008) A comparison of epinephrine and norepinephrine in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 34:2226–2234

Abraham WT, Adams KF, Fonarow GC et al (2005) In-hospital mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure requiring intravenous vasoactive medications: an analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). J Am Coll Cardiol 46:57–64

Shahin J, DeVarennes B, Tse CW et al (2011) The relationship between inotrope exposure, six-hour postoperative physiological variables, hospital mortality and renal dysfunction in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Crit Care 15:R162

Boldt J, Menges T, Kuhn D et al (1995) Alterations in circulating vasoactive substances in the critically ill: a comparison between survivors and non-survivors. Intensive Care Med 21:218–225

Brown SM, Lanspa MJ, Jones JP et al (2013) Survival after shock requiring high-dose vasopressor therapy. Chest 143:664–671

Leibovici L, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M et al (2007) Relative tachycardia in patients with sepsis: an independent risk factor for mortality. QJM 100:629–634

Dünser MW, Ruokonen E, Pettilä V et al (2009) Association of arterial blood pressure and vasopressor load with septic shock mortality: a post hoc analysis of a multicenter trial. Crit Care 13:R181

Hagihara A, Hasegawa M, Abe T et al (2012) Prehospital epinephrine use and survival among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 307:1161–1168

Dumas F, Bougouin W, Geri G et al (2014) Is epinephrine during cardiac arrest associated with worse outcome in resuscitated patients? J Am Coll Cardiol 64:2360–2367

Asfar P, Meziani F, Hamel JF et al (2014) High versus low blood-pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med 370:1583–1593

Gattinoni L, Brazzi L, Pelosi P et al (1995) A trial of goal-oriented hemodynamic therapy in critically ill patients. SvO2 Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med 333:1025–1032

López A, Lorente JA, Steingrub J et al (2004) Multiple-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 546C88: effect on survival in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 32:21–30

Vincent JL, Privalle CT, Singer M et al (2015) Multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study of pyridoxalated hemoglobin polyoxyethylene in distributive shock (PHOENIX). Crit Care Med 43:57–64

De Cruz SJ, Kenyon NJ, Sandrock CE (2009) Bench-to-bedside review: the role of nitric oxide in sepsis. Expert Rev Respir Med 3:511–521

Aronoff DM (2012) Cyclooxygenase inhibition in sepsis: is there life after death? Mediat Inflamm 2012:696897

Chawla LS, Busse L, Brasha-Mitchell E et al (2014) Intravenous angiotensin II for the treatment of high-output shock (ATHOS trial): a pilot study. Crit Care 18:534–539

Lange M, Morelli A, Westphal M (2008) Inhibition of potassium channels in critical illness. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 21:105–110

Schortgen F, Clabault K, Katsahian S et al (2012) Fever control using external cooling in septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185:1088–1095

Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J et al (2008) Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med 358:877–887

Morelli A, De Castro S, Teboul JL et al (2005) Effects of levosimendan on systemic and regional hemodynamics in septic myocardial depression. Intensive Care Med 31:638–644

Hamdulay SS, Al-Khafaji A, Montgomery H (2006) Glucose–insulin and potassium infusions in septic shock. Chest 129:800–804

Orme RM, Perkins GD, McAuley DF et al (2014) An efficacy and mechanism evaluation study of Levosimendan for the Prevention of Acute oRgan Dysfunction in Sepsis (LeoPARDS): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 15:199

Saito T, Takanashi M, Gallagher E et al (1995) Corticosteroid effect on early beta-adrenergic down-regulation during circulatory shock: hemodynamic study and beta-adrenergic receptor assay. Intensive Care Med 21:204–210

Sakaue M, Hoffman BB (1991) Glucocorticoids induce transcription and expression of the alpha 1B adrenergic receptor gene in DTT1 MF-2 smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest 88:385–389

Annane D, Bellissant E (2000) Prognostic value of cortisol response in septic shock. JAMA 284:308–309

Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D (2008) Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med 358:111–124

Morelli A, Ertmer C, Westphal M et al (2013) Effect of heart rate control with esmolol on hemodynamic and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 310:1683–1691

Ackland GL, Yao ST, Rudiger A et al (2010) Cardioprotection, attenuated systemic inflammation, and survival benefit of beta1-adrenoceptor blockade in severe sepsis in rats. Crit Care Med 38:388–394

Christensen S, Johansen MB, Tønnesen E et al (2011) Preadmission beta-blocker use and 30-day mortality among patients in intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care 15:R87

Macchia A, Romero M, Comignani PD et al (2012) Previous prescription of β-blockers is associated with reduced mortality among patients hospitalized in intensive care units for sepsis. Crit Care Med 40:2768–2772

Aboab J, Sebille V, Jourdain M et al (2011) Effects of esmolol on systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics and on oxygenation in pigs with hypodynamic endotoxin shock. Intensive Care Med 37:1344–1351

Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Maeda H et al (2009) Landiolol, an ultrashort-acting beta1-adrenoceptor antagonist, has protective effects in an LPS-induced systemic inflammation model. Shock 31:515–520

Suzuki T, Morisaki H, Serita R et al (2005) Infusion of the beta-adrenergic blocker esmolol attenuates myocardial dysfunction in septic rats. Crit Care Med 33:2294–2301

Mori K, Morisaki H, Yajima S et al (2011) Beta-1 blocker improves survival of septic rats through preservation of gut barrier function. Intensive Care Med 37:1849–1856

Wilson J, Higgins D, Hutting H, Serkova N et al (2013) Early propranolol treatment induces lung heme-oxygenase-1, attenuates metabolic dysfunction, and improves survival following experimental sepsis. Crit Care 17:R195

Morelli A, Donati A, Ertmer C et al (2013) Microvascular effects of heart rate control with esmolol in patients with septic shock: a pilot study. Crit Care Med 41:2162–2168

Heilbrunn SM, Shah P, Bristow MR et al (1989) Increased beta-receptor density and improved hemodynamic response to catecholamine stimulation during long-term metoprolol therapy in heart failure from dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 79:483–490

Berk JL, Hagen JF, Dunn JM (1970) The role of beta adrenergic blockade in the treatment of septic shock. Surg Gynecol Obstet 130:1025–1034

Gore DC, Wolfe RR (2006) Hemodynamic and metabolic effects of selective beta1 adrenergic blockade during sepsis. Surgery 139:686–694

Schmitz D, Wilsenack K, Lendemanns S et al (2007) Beta-adrenergic blockade during systemic inflammation: impact on cellular immune functions and survival in a murine model of sepsis. Resuscitation 72:286–294

Wurtman RJ (1966) Control of epinephrine synthesis by the pituitary and adrenal cortex: possible role in the pathophysiology of chronic stress. Recent Adv Biol Psychiatry 9:359–368

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Fabio Zugni, MD, for invaluable technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andreis, D.T., Singer, M. Catecholamines for inflammatory shock: a Jekyll-and-Hyde conundrum. Intensive Care Med 42, 1387–1397 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4249-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4249-z