Abstract

Purpose

The spontaneous breathing trial (SBT)—relying on objective criteria assessed by the clinician—is the major diagnostic tool to determine if patients can be successfully extubated. However, little is known regarding the patient’s subjective perception of autonomous breathing.

Methods

We performed a prospective observational study in 211 mechanically ventilated adult patients successfully completing a SBT. Patients were randomly assigned to be interviewed during this trial regarding their prediction of extubation success. We compared post-extubation outcomes in three patient groups: patients confident (confidents; n = 115) or not (non-confidents; n = 38) of their extubation success and patients not subjected to interview (control group; n = 58).

Results

Extubation success was more frequent in confidents than in non-confidents (90 vs. 45%; p < 0.001/positive likelihood ratio = 2.00) or in the control group (90 vs. 78%; p = 0.04). On the contrary, extubation failure was more common in non-confidents than in confidents (55 vs. 10%; p < 0.001/negative likelihood ratio = 0.19). Logistic regression analysis showed that extubation success was associated with patient’s prediction [OR (95% CI): 9.2 (3.74–22.42) for confidents vs.non-confidents] as well as to age [0.72 (0.66–0.78) for age 75 vs. 65 and 1.31 (1.28–1.51) for age 55 vs. 65].

Conclusions

Our data suggest that at the end of a sustained SBT, extubation success might be correlated to the patients’ subjective perception of autonomous breathing. The results of this study should be confirmed by a large multicenter trial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rapid discontinuation of mechanical ventilation is an essential issue for both critically ill patients and clinicians, but controversy still exists as to the best approach for conducting this task [1]. Its correct timing is crucial, as both premature and unreasonably delayed extubation are associated with adverse outcomes [2–7].

It is presently recommended to perform weaning by means of an evidence-based two-step approach, in which daily evaluation for readiness to wean is followed by extubation after a successful spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) [1, 2]. The SBT is presently the major diagnostic tool to determine if patients can be successfully extubated [1], and recent recommendations have been made to further increase the likelihood of successful extubation [8–15]. Nonetheless, extubation failure—defined as the need for ventilatory support or death within 48 h following extubation (adapted from [1])—is still prevalent, with reported reintubation rates of up to 19% [1, 16, 17] and 5–24% for rescue therapy with non-invasive ventilation (NIV) [13–15].

The recommended approaches to evaluate the likelihood of successful extubation rely on objective criteria assessed by the clinician [1–15]. Little emphasis has been placed so far on the patients’ subjective evaluation of the potential to sustain autonomous breathing, which might be influenced by psychological factors as well as the perceived work of breathing. In the few studies that have investigated subjective criteria during weaning [18, 19], dyspnea was significantly associated with fatigue and patients’ lack of confidence in their ability to breathe without ventilatory support [18], whereas lack of dyspnea—along with the rapid shallow breathing index—was identified as the best predictor of successful weaning [19]. However, no study has so far tested the prognostic value of subjective perceptions for predicting extubation success.

The aim of our study was to prospectively assess the patient’s capacity to predict extubation outcome before and at the end of a SBT.

Methods

Patients and Setting

This prospective, observational study was conducted in the mixed 9-bed Intensive Care Unit of a regional teaching hospital (Bellinzona) and the mixed 36-bed Intensive Care Unit of a university hospital (Geneva). This investigation was approved by the local ethics committees, which waived written, informed consent and registered in the Clinical Trials.gov-Protocol Registration System as “Prediction of extubation success by the patient” (NCT00448565).

Between November 2006 and December 2008, consecutive patients ≥18 years of age, requiring invasive mechanical ventilation for ≥10 h (thereby excluding patients with immediate, uncomplicated postoperative extubation) were eligible when they were considered ready to sustain a SBT (details are provided in the online supplement). Exclusion criteria were the need for tracheostomy, neurological deficits presumably precluding patient cooperation (e.g., traumatic brain injury), terminal weaning, failure of ≥2 SBT and absence of a primary investigator during the SBT.

Study protocol

Patients showing stabilization or reversal of the underlying cause of acute respiratory failure were continuously assessed by caregivers (physicians in charge of the patient and experienced and specialized ICU-nurses) in view of the readiness criteria for the SBT. Mentation was assessed by the Glasgow Coma Scale and the Sedation-Agitation Scale or Richmond-Agitation-Sedation Scale, respectively. Sedation was carefully titrated and eventually stopped. Patients were considered competent to undergo the questioning when they had an adequate mentation (awake and cooperative), and were able to give reproducible answers and carry out orders. Eligible patients were indicated to the investigators, who randomly assigned them to be interviewed (70%) or not (30%) about their personal prediction of extubation success. Randomization was done in a blinded fashion, using opaque, sealed and numbered envelopes kept in the administrative office of each center. The interview was carried out at two distinct moments: (1) immediately before the SBT and (2) at the end of the SBT (with SBT ventilator setting). Patients were asked the following question: “do you feel able to breathe without the help of the machine” (they were informed that their probability to sustain autonomous breathing was now determined by means of a SBT, followed by a concise explanation regarding the meaning and consequences of the term extubation)? The patient’s non-verbal answer (by nodding or head shaking) was recorded as yes (clearly affirmative), no (clearly negative) or do not know (ambiguous answer, impossibility to adequately interpret the patient’s answer). A patient’s response was retained as valid and thus recorded as yes or no when it was correctly repeated once; otherwise, it was considered an ambiguous answer. In order to avoid any Hawthorne effect (a positive or beneficial effect on a person or group performing at a higher level of efficiency because of knowledge being observed [20]), we did not inform our interns and nurses about the ongoing study. All patients from the intervention group were informed and interviewed exclusively by the investigators and in the absence of other caregivers; for control group patients, an analogous procedure was simulated (presence of an investigator in the visually shielded room without the patient being interviewed).

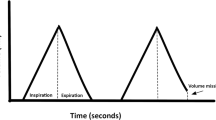

While preparing for the SBT the ventilator was switched to pressure support ventilation (if not already in use for treatment of acute respiratory failure) with 12 cmH2O inspiratory pressure support in order to carry out the first interview. Afterwards, the SBT of 30–120-min duration was performed with 7 cmH2O inspiratory pressure support and 5 cmH2O positive end-expiratory pressure (without automatic tube compensation). All patients who successfully completed the SBT were immediately extubated, while those failing (see online supplement) were reassessed 24 h later. The decision for extubation was taken by the caregivers who were blinded to the patient’s prediction of extubation outcome. Extubation was performed during the daytime only in order to ensure optimal support by respiratory therapists. The study investigators were excluded from the routine care of patients and decision making (extubation, rescue NIV or reintubation).

Immediate reintubation was performed in the presence of a major clinical event (see online supplement). The appearance of at least one criterion defining respiratory failure after extubation prompted immediate rescue therapy with NIV. The rescue therapy with NIV was considered inappropriate (and required immediate reintubation) at the appearance of any major clinical event (see above).

Data collection and definitions

Patients’ general characteristics and relevant data for the study were prospectively recorded from medical records and bedside flow charts. The causes of respiratory failure after extubation leading to NIV or reintubation were documented, and the follow-up was continued until ICU discharge or death.

Extubation success was defined as absence of death or need for ventilatory support within 48 h after extubation (adapted from [1]). Patients giving a clearly affirmative answer regarding the specific question mentioned above were defined as confidents, whereas those who predicted their inability to breathe independently or gave an ambiguous answer, respectively, were termed non-confidents. Patients with sham interviews were assigned to the control group.

Statistical analysis

Sample size estimation

Based on previous results [13, 14] and our local experience [21], we expected a 20% overall rate of extubation failure (10% reintubation and 10% rescue NIV). We hypothesized that confidents would show a 50% reduction in extubation failure (from 20 to 10%) and non-confidents an increase of 50% (from 20 to 30%), with an a priori assumption of the same population in each group. Thus, the sample size required to detect a 20% difference between the two groups with a power of 80% was 144. A control group representing a similar sample size as each experimental group was created by randomization.

Comparison between groups

We compared outcomes between confidents and non-confidents; the control group served as a comparator for the whole interview group. We distinguished between true positives (TP; confidents + extubation success), false positives (FP; confidents + extubation failure), true negatives (TN; non-confidents + extubation failure) and false negatives (FN; non-confidents + extubation success). The primary end point was extubation success in confidents compared to non-confidents.

For the intervention groups, the association between extubation success and the patients’ prediction (ordinal scale: no, ambiguous, yes) was measured with a Spearman ρ coefficient. Unless specified, the comparison between different groups for continuous values was performed with an analysis of variance, and Fisher (when applicable) or chi-square test for nominal values. A logistic regression model was used to investigate the link between extubation success and the following variables: effect of study site and investigator, gender and age of the patient, SAPS II and the patients’ prediction. Variables taken into account for the final model were selected using as a first step the covariates gender, age and SAPS II, then by backward and forward selection. All of the analyses where performed with TIBCO Spotfire S+® 8.1 for Windows.

Results

Out of 887 patients subjected to invasive mechanical ventilation during the study period, 211 were ultimately included in the study and analyzed (Fig. 1): 153 were allocated to be interviewed and 58 to the control group. Most patients (204/211) were extubated after their first SBT (6 of the 7 patients, 86% who failed their first SBT were not-confident at that time); 200 of 211 (95%) patients underwent a 30-min trial. Statistical analysis did not reveal any difference in outcome between interviewers or centers. Extubation success in the whole experimental group (120 of 153, 78%) was similar to that of the control group (45 of 58, 78%), and their baseline characteristics were comparable (see online supplement).

As shown in Table 1, the patients’ prediction of extubation success varied according to the timing of the interview. Prior to the SBT, the patient’s perception was imprecise (positive predictive value: 0.80; Spearman ρ = 0.068 with p = 0.40). A more accurate prediction was obtained at the end of the SBT (positive predictive value: 0.90; ρ = 0.499; p < 0.001), and therefore evaluation results all refer to end of SBT timing.

At the end of the sustained SBT, 115 patients were confidents and 38 were non-confidents. Comparison within experimental groups revealed younger age and fewer risk factors for extubation failure in confidents (Table 2). As depicted in Table 3, extubation success was more frequent in confidents than in non-confidents (90 vs. 45%; p < 0.001/positive likelihood ratio = 2.00). On the contrary, non-confidents were more frequently associated with rescue therapy with NIV than confidents (39 vs. 8%; p < 0.001), to reintubation (16 vs. 3%; p = 0.008) or both (55 vs. 10%; p = 0.001/negative likelihood ratio = 0.19). No death was observed within 48 h following extubation. Other clinical outcomes according to the patients’ perception are listed in Table 3.

The reasons for extubation failure are listed in Table 3. Immediate rescue therapy with NIV avoided reintubation in 9 of 10 (90%) confident patients and 15 of 18 (83%) non-confident patients (p = 0.99). Reintubated patients had a higher mortality (3 of 11, 27%) than those needing a rescue therapy with NIV (4 of 35, 11%) or being successfully extubated (2 of 165, 1%).

A logistic regression analysis showed that extubation success was associated with patient prediction as well as to age (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study suggests that extubation success might be correlated to the patient’s subjective perception. In fact, at the end of a sustained SBT, 90% of confidents were successfully extubated as compared to 78% of the control group and 45% of non-confidents. Although non-confidents had a relatively high false-negative prediction rate, this interview approach might add another valuable tool in helping clinicians to assess patients deemed ready for extubation without pretending to be a new gold standard.

The patients’ prediction was probably associated with the work of breathing at the time the question was asked, since the interview performed at the end of the SBT yielded more accurate results. From a pathophysiological point of view, these findings make sense, as the higher inspiratory pressure support prior to the SBT (≤12 cmH2O) probably overcompensated the resistance and the dead space imposed by the ventilator circuit, compared to the lower level applied during the SBT (7 cmH2O). One might ask how and what do patients with negative confidence experience that goes unobserved by clinicians or is not detected by objective criteria? A close examination of this group of patients during future trials might generate new successful predictors. Another interesting point, confirming the need to chose the right timing for a more accurate prediction, is that 23 out of 38 patients with an ambiguous answer prior to the SBT were finally confident at the end of the SBT with a 100% extubation success, whereas only 70% of those remaining ambiguous were successfully extubated, and all five patients becoming non-confident had an extubation failure (two rescue therapies with NIV, two reintubations, one death).

Confident patients exhibited a 90% successful extubation rate, findings superior to those observed in the control group (78%) and to the rates reported in the literature [1, 13–17]. Although this result did not reach significance, the low p value brings evidence that one may expect to confirm this trend by means of a larger trial. Conversely, patients’ negative prediction of their post-extubation respiratory autonomy, although having successfully passed a SBT, should be taken seriously: more than half actually undergo extubation failure within 48 h.

While the enhanced predictive value of the interview in the confident patients would suggest its addition to the weaning strategy of intubated patients, the question of what to do with non-confidents is more difficult to answer. One might suggest that those patients could be candidates for the early application of prophylactic NIV, since the main reason for extubation failure was signs of increased respiratory muscle load. This proposal would be in line with results from studies showing the beneficial impact of such an approach [13–15, 22]. Interestingly, and as shown in Table 2, non-confidents expressed risk factors for extubation failure [13] significantly more often than confidents.

Our study presents several limitations. First, this study was performed solely in two ICUs and on a relatively small sample size. Moreover, about 40% of the patients were post-surgical (major abdominal and thoracic surgery), a group that generally presents less difficulty in weaning. Nonetheless, we believe that the data are very promising as statistical analysis did not reveal any difference in outcome between different interviewers or centers. Second, knowledge of the ongoing study might theoretically have stimulated nurses and respiratory physiotherapists to manage confident patients more “intensely” than the others. However, in order to avoid any Hawthorne effect [20], we did not inform them about the content of the ongoing study; in addition we tried to minimize this concern by random selection of the patients to be interviewed and simulating the procedure in the control group. Furthermore, all patients were clinically assessed and eventually interviewed exclusively by the investigators and in the absence of any other caregiver. Third, the study does not allow conclusions about a possible benefit in delaying the extubation of non-confident patients, as ethical reasons warranted extubation after a sustained SBT (gold standard). Fourth, our inclusion criterion regarding the duration of mechanical ventilation (≥10 h) may have favorably affected extubation outcome. However, most patients (84%) were ventilated for more than 24 h (as proposed by [2]), and statistical evaluation did not reveal any correlation between duration of mechanical ventilation and extubation outcome or patient’s prediction, respectively. Fifth, as we frequently tracheotomize patients with prolonged weaning [1], we were not able to ascertain whether the patients’ perception of extubation success may vary according to the difficulty and duration of their weaning process. Accordingly, our results apply primarily to patients with simple weaning. Finally, we only included awake and cooperative patients, whereas Boles et al. [1] suggested a somewhat less precise criterion (adequate mentation).

In conclusion, our data suggest that at the end of a sustained SBT, extubation success might be correlated to the patients’ subjective perception of autonomous breathing. The results of this study should be confirmed by a large multicenter trial.

References

Boles J-M, Bion J, Connors A, Herridge M, Marsh B, Melote C, Pearl R, Silverman H, Stanchina M, Vieillard-Baron A, Welte T (2007) Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Statement of the Sixth International Consensus Conference on Intensive Care Medicine organized jointly by the European Respiratory Society (ERS), the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the Société de Réanimation de Langue Francaise (SRLF), and approved by the ERS Executive Committee, February 2007. Eur Respir J 29:1033–1056

MacIntyre NR, Cook DJ, Ely EW Jr, Epstein SK, Fink JB, Heffner JE, Hess D, Hubmayer RD, Scheinhorn DJ (2001) Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support: a collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; American Association for Respiratory Care; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 120(6 Suppl):375S–395S

Coplin WM, Pierson DJ, Cooley KD, Newell DW, Rubenfeld GD (2000) Implications of extubation delay in brain-injured patients meeting standard weaning criteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161:1530–1536

Epstein SK, Ciubotaru RL, Wong JB (1997) Effect of failed extubation on the outcome of mechanical ventilation. Chest 112:186–192

Esteban A, Alia I, Tobin MJ, Gil A, Gordo F, Vallverdù I, Blanch L, Bonet A, Vázquez A, de Pablo R, Torres A, de la Cal MA, Macías S (1999) Effect of spontaneous breathing trial duration on outcome of attempts to discontinue mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159:512–518

Esteban A, Alia I, Gordo F, Fernández R, Solsona JF, Vallverdù I, Macías S, Allegue JM, Blanco J, Carriedo D, León M, de la Cal MA, Taboado F, de Velasco JG, Palazón E, Carrizosa F, Tomás R, Suarez J, Goldwasser RS (1997) Extubation outcome after spontaneous breathing trials with T-tube or pressure support ventilation. The Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156:459–465

Epstein SK, Ciubotaru RL (1998) Independent effects of etiology of failure and time to reintubation on outcome for patients failing extubation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158:489–493

Mekontso-Dessap A, de Prost N, Girou E, Braconnier F, Lemaire F, Brun-Buisson C, Brochard L (2006) B-type natriuretic peptide and weaning from mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 32:1529–1536

Upadya A, Tilluckdharry L, Muralidharan V, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA (2005) Fluid balance and weaning outcomes. Intensive Care Med 31:1643–1647

Frutos-Vivar F, Ferguson ND, Esteban A, Epstein SK, Arabi Y, Apezteguia C, Gonzalez M, Hill NS, Nava S, D’Empaire G, Anueto A (2006) Risk factors for extubation failure in patients following a successful spontaneous breathing trial. Chest 130:1664–1671

Ochoa ME, del Carmen Marin M, Frutos-Vivar F, Gordo F, Latour-Pérez J, Calvo E, Esteban A (2009) Cuff-leak test for the diagnosis of upper airway obstruction in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 35:1171–1179

McCaffrey J, Farrell C, Whiting P, Dan A, Bagshaw SM, Delaney AP (2009) Corticosteroids to prevent extubation failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 35:977–986

Ferrer M, Valencia M, Nicolas JM, Bernadich O, Badia JR, Torres A (2006) Early noninvasive ventilation averts extubation failure in patients at risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173:164–170

Navalesi P, Frigerio P, Moretti MP, Sommariva M, Vesconi S, Baiardi P, Levati A (2008) Rate in reintubation in mechanically ventilated neurosurgical and neurologic patients: evaluation of a systematic approach to weaning and extubation. Crit Care Med 36:2986–2992

Nava S, Gregoretti C, Fanfulla F, Squadrone E, Grassi M, Carlucci A, Beltrame F, Navalesi P (2005) Noninvasive ventilation to prevent respiratory failure after extubation in high-risk patients. Crit Care Med 33:2465–2470

Vallverdu I, Calaf N, Subirana M, Net A, Benito S, Mancebo J (1998) Clinical characteristics, respiratory functional parameters, and outcome of a two-hour T-piece trial in patients weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158:1855–1862

Esteban A, Frutos F, Tobin MJ, Alía I, Solsona JF, Valverdú I, Fernández R, de la Cal MA, Benito S, Tomás R, Carriedo D, Macías S, Blanco J, Spanish Lung Failure Collaborative Group (1995) A comparison of four methods of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med 332:345–350

Twibell R, Siela D, Mahmoodi M (2003) Subjective perceptions and physiological variables during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care 12:101–112

Moody LE, Lowry L, Yarandi H, Voss A (1997) Psychophysiologic predictors of weaning from mechanical ventilation in chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Clin Nurs Res 6:311–330

Mayo E (1933) The human problems of an industrial civilization. Macmillan, New York

Perren A, Domenighetti G, Mauri S, Genini F, Vizzardi N (2002) Protocol-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation: clinical outcome in patients randomized for a 30-min or 120-min trial with pressure support ventilation. Intensive Care Med 28:1058–1063

Antonelli M, Conti G, Bufi M, Costa MG, Lappa A, Rocco M, Gasparetto A, Meduri GU (2000) Noninvasive ventilation for treatment of acute respiratory failure in patients undergoing solid organ transplantation: a randomized trial. JAMA 283:235–241

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Renata Marchetti for secretarial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perren, A., Previsdomini, M., Llamas, M. et al. Patients’ prediction of extubation success. Intensive Care Med 36, 2045–2052 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-010-1984-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-010-1984-4