Abstract

Objective

To explore the relationship between lactate:pyruvate ratio, hyperlactataemia, metabolic acidosis, and morbidity.

Design and setting

Prospective observational study in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) of a university hospital.

Patients

Ninety-seven children after open cardiac surgery. Most children (94%) fell into low-moderate operative risk categories; observed PICU mortality was 1%.

Interventions

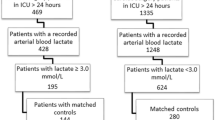

Blood was sampled on admission for acid-base analysis, lactate, and pyruvate. Metabolic acidosis was defined as standard bicarbonate lower than 22 mmol/l, raised lactate as higher than 2 mmol/l, and raised lactate:pyruvate ratio as higher than 20.

Measurements and results

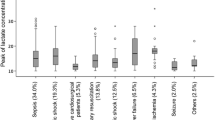

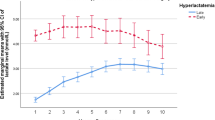

Median cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross-clamp times were 80 and 46 min. Metabolic acidosis occurred in 74%, hyperlactataemia in 42%, and raised lactate:pyruvate ratio in 45% of children. In multivariate analysis lactate:pyruvate ratio increased by 6.4 in children receiving epinephrine infusion and by 0.4 per 10 min of aortic cross-clamp. Duration of inotropic support increased by 0.29 days, ventilatory support by 0.27 days, and PICU stay by 0.42 days, for each 1 mmol/l increase in lactate. Neither standard bicarbonate nor lactate:pyruvate ratio were independently associated with prolongation of PICU support.

Conclusions

Elevated lactate:pyruvate ratio was common in children with mild metabolic acidosis and low PICU mortality. Hyperlactataemia, but not elevated lactate:pyruvate ratio or metabolic acidosis, was associated with prolongation of PICU support. Routine measurement of lactate:pyruvate ratio is not warranted for children in low-moderate operative risk categories.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Duke T, Butt W, South M, Karl TR (1997) Early markers of major adverse events in children after cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 114:1042–1052

Siegel LB, Dalton HJ, Hertzog JH, Hopkins RA, Hannan RL, Hauser GJ (1996) Initial postoperative serum lactate levels predict survival in children after open heart surgery. Intensive Care Med 22:1418–1423

Hatherill M, Sajjanhar T, Tibby SM, Champion MP, Anderson D, Marsh MJ, Murdoch IA (1997) Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality after paediatric cardiac surgery. Arch Dis Child 77:235–238

Cheifetz IM, Kern FH, Schulman SR, Greeley WJ, Ungerleider RM, Meliones JN (1997) Serum lactates correlate with mortality after operations for complex congenital heart disease. Ann Thorac Surg 64:735–738

Rossi AF, Khan DM, Hannan R, Bolivar J, Zaidenweber M, Burke R (2005) Goal-directed medical therapy and point-of-care testing improve outcomes after congenital heart surgery. Intensive Care Med 31:98–104

Frey B, Macrae DJ (2005) Goal-directed therapy may improve outcome in complex patients-depending on the chosen treatment end point. Intensive Care Med 31:508–509

Hannan RL, Ybarra MA, White JA, Ojito JW, Rossi AF, Burke RP (2005) Patterns of lactate values after congenital heart surgery and timing of cardiopulmonary support. Ann Thorac Surg 80:1468–1473

Duke T (1999) Dysoxia and lactate. Arch Dis Child 81:343–350

James JH, Luchette FA, McCarter FD, Fischer JE (1999) Lactate is an unreliable indicator of tissue hypoxia in injury or sepsis. Lancet 354:505–508

Sumpelmann R, Schurholz T, Thorns E, Hausdorfer J (2001) Acid-base, electrolyte and metabolite concentrations in packed red blood cells for major transfusion in infants. Paediatr Anaesth 11:169–173

Toda Y, Duke T, Shekerdemian LS (2005) Influences on lactate levels in children early after cardiac surgery: prime solution and age. Crit Care Resusc 7:87–91

Sandstrom K, Nilsson K, Andreasson S, Larsson LE (1999) Open heart surgery; pump prime effects and cerebral arteriovenous differences in glucose, lactate and ketones. Paediatr Anaesth 9:53–59

Li J, Schulze-Neick I, Lincoln C, Shore D, Scallan M, Bush A, Redington AN, Penny DJ (2000) Oxygen consumption after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in children: determinants and implications. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 119:525–533

Ganushchak YM, Maessen JG, de Jong DS (2002) The oxygen debt during routine cardiac surgery: illusion or reality? Perfusion 17:167–173

Durward A, Tibby SM, Skellett S, Austin C, Anderson D, Murdoch IA (2005) The strong ion gap predicts mortality in children following cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med 6:281–285

Murray DM, Olhsson V, Fraser JI (2004) Defining acidosis in postoperative cardiac patients using Stewart's method of strong ion difference. Pediatr Crit Care Med 5:240–245

Hatherill M, Salie S, Waggie Z, Lawrenson J, Hewitson J, Reynolds L, Argent A (2005) Hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis following open cardiac surgery. Arch Dis Child 90:1288–1292

Levy B, Bollaert PE, Charpentier C, Nace L, Audibert G, Bauer P, Nabet P, Larcan A (1997) Comparison of norepinephrine and dobutamine to epinephrine for hemodynamics, lactate metabolism, and gastric tonometric variables in septic shock: a prospective, randomized study. Intensive Care Med 23:282–287

Levy B, Sadoune LO, Gelot AM, Bollaert PE, Nabet P, Larcan A (2000) Evolution of lactate/pyruvate and arterial ketone body ratios in the early course of catecholamine-treated septic shock. Crit Care Med 28:114–119

Gallet D, Goudable J, Vedrinne JM, Viale JP, Annat G (1997) Increased lactate/pyruvate ratio with normal beta-hydroxybutyrate/acetoacetate ratio and lack of oxygen supply dependency in a patient with fatal septic shock. Intensive Care Med 23:114–116

Suistomaa M, Ruokonen E, Kari A, Takala J (2000) Time-pattern of lactate and lactate to pyruvate ratio in the first 24 hours of intensive care emergency admissions. Shock 14:8–12

Weil MH, Afifi AA (1970) Experimental and Clinical Studies on Lactate and Pyruvate as Indicators of the Severity of Acute Circulatory Failure (Shock). Circulation 41:989–1001

De Pinieux G, Chariot P, Ammi-Said M, Louarn F, Lejonc JL, Astier A, Jacotot B, Gherardi R (1996) Lipid-lowering drugs and mitochondrial function: effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on serum ubiquinone and blood lactate/pyruvate ratio. Br J Clin Pharmacol 42:333–337

Jenkins KJ, Newburger JW, Lock JE, Davis RB, Coffman GA, Iezzoni LI (1995) In-hospital mortality for surgical repair of congenital heart defects: preliminary observations of variation by hospital caseload. Pediatrics 95:323–330

Shann F, Pearson G, Slater A, Wilkinson K (1997) Paediatric index of mortality (PIM): a mortality prediction model for children in intensive care. Intensive Care Med 23:201–207

Hatherill M, Waggie Z, Purves L, Reynolds L, Argent A (2002) Correction of the anion gap for albumin in order to detect occult tissue anions in shock. Arch Dis Child 87:526–529

Druml W, Grimm G, Laggner AN, Lenz K, Schneeweiss B (1991) Lactic acid kinetics in respiratory alkalosis. Crit Care Med 19:1120–1124

Dugas MA, Proulx F, de Jaeger A, Lacroix J, Lambert M (2000) Markers of tissue hypoperfusion in pediatric septic shock. Intensive Care Med 26:75–83

Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K (2002) Center-specific differences in mortality: preliminary analyses using the Risk Adjustment in Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1) method. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 124:97–104

Acknowledgements

This manuscript comprises a partial fulfilment of the requirements for an M.D. thesis (M.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Funded in part by a grant from the Institute of Child Health, University of Cape Town (M.H.)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hatherill, M., Salie, S., Waggie, Z. et al. The lactate:pyruvate ratio following open cardiac surgery in children. Intensive Care Med 33, 822–829 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0593-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0593-3