Abstract

Background

Poor transitions to adult care from child and adolescent mental health services may increase the risk of disengagement and long-term negative outcomes. However, studies of transitions in mental health care are commonly difficult to administer and little is known about the determinants of successful transition. The persistence of health inequalities related to access, care, and outcome is now well accepted including the inverse care law which suggests that those most in need of services may be the least likely to obtain them. We sought to examine the pathways and determinants of transition, including the role of social class.

Method

A retrospective systematic examination of electronic records and case notes of young people eligible to transition to adult care over a 4-year period across five Health and Social Care NHS Trusts in Northern Ireland.

Results

We identified 373 service users eligible for transition. While a high proportion of eligible patients made the transition to adult services, very few received an optimal transition process and many dropped out of services or subsequently disengaged. Clinical factors, rather than social class, appear to be more influential in the transition pathway. However, those not in employment, education or training (NEET) were more likely (OR 3.04: 95% CI 1.34, 6.91) to have been referred to Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS), as were those with a risk assessment or diagnosis (OR 4.89: 2.45, 9.80 and OR 3.36: 1.78, 6.34), respectively.

Conclusions

Despite the importance of a smoother transition to adult services, surprisingly, few patients experience this. There is a need for stronger standardised policies and guidelines to ensure optimal transitional care to AMHS. The barriers between different arms of psychiatry appear to persist. Joint working and shared arrangements between child and adolescent and adult mental health services should be fostered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transition from Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) to Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS) is a major concern for many young service users (SU) and their parents/carers. Poorly planned transitions may provoke increased risk of non-adherence to treatment, loss to follow-up, and poorer health outcomes [1, 2], with considerable economic costs [3, 4]. Current evidence suggests that young people with mental disorders such as psychosis are more likely to transition to adult services than those with other conditions such as neuro-developmental and personality disorders [5, 6]. In addition, approximately one-third of young people are lost from care during transition and a further third may experience an interruption in their care [7]. Differences have been noted in the theoretical and conceptual views of diagnosis and treatment between clinicians in CAMHS and their AMHS counterparts, and these oppositional perspectives may create barriers at the interface. In addition, service access, treatment, and outcomes may vary considerably between similar patients depending on beliefs, attitudes, and preferences of both patients and service providers [8]. However, inequalities associated with health care access, notable even within universal health insurance systems [9,10,11], have not been examined in relation with transition. In addition to service mapping and qualitative longitudinal research components, with service users, families, and clinicians, the IMPACT study (Improving Mental Health Pathways and Care for Adolescents in Transition to Adult Services in Northern Ireland) undertook an examination of transition pathways.

Aims

We examined the transition process to: (a) trace SU progression through service boundaries and (b) determine outcomes in terms of the referral process and level of engagement with services. In addition, we examined the extent that social class and aspects of SU family background such as family history of mental illness were predictors of transition outcomes.

Method

A retrospective systematic analysis of electronic records and case notes of young people eligible to transition to adult mental health services over a 4-year period.

Sample

The TRACK study in England [12] suggests that the rate of transition from CAMHS to adult care is approximately 20 adolescents per million of the general population per year. On this basis, we estimated that a minimum of 168 transition cases would be available [allowing that cases were collected over a 4 year period, and a Northern Ireland (NI) population of approximately 1.8 million people]. Formally, the criteria for inclusion were attendance at CAMHS between January 2010 and December 2014 and reaching the transition boundary (at age 18) during that time period.

Data retrieval and instruments

From hospital records, we identified service users during the study period, recording the referral date, referral problem, date seen, diagnosis, treatment provided, engagement with service and outcome (either discharged or case still open). We identified the following service user types: (1) those at the appropriate age for transition (locally defined by protocol), considered for transfer and expected to have on-going needs; (2) those being seen by CAMHS because of the lack of an adequate/appropriate adult service; and (3) those discharged or disengaged from CAMHS with a continuing mental health problem (but not referred to AMHS). From the AHMS database, we identified individuals referred to AHMS, including those younger than the recognised age cutoff.

Information used in the study was collected through electronic databases and case notes held by the five NI Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts (the integrated equivalent of the NHS in NI). Members of the research team (SMcG, PF) identified patients eligible for inclusion through a combination of electronic and manual searches of the records. The various sources of data were obtained from Trust-specific information systems, creating potential difficulties in identifying those meeting the inclusion criteria. Service managers assisted in identifying potential missing cases. In addition, we examined minutes from transition meetings and handwritten records to identify the potential referrals. In the initial stages of data extraction we performed an inter-rater reliability test, checking the proforma for coherence.

A set of three electronic questionnaires, adapted from the TRACK study [5] to suit the NI context, were used to capture information linked with the transition process (available on request). The amended questionnaires, checked for face and content validity with CAMHS and AMHS clinicians, also contained a section on external agency involvement. This included: (a) GP referral and engagement with treatment and care; (b) other governmental agencies, e.g. social care for Looked After Children (LAC); and (c) voluntary sector agency involvement. It also captured the presenting problem at the time of referral, outcome of referral to AMHS (whether accepted by adult services, retained or referred elsewhere), time from referral date to transfer, potential barriers to transition including quality of information, contact frequency, types of contact and contacting agencies.

We noted the existence, timing and level of adherence to a transition care plan and reasons for deviation. For all cases the following was recorded: (a) client information, including socio-demographic data (age, sex, education/occupation/training, ethnicity, status as LAC and, if noted, sexual orientation); (b) parental and family information (including people living at home, history of parental mental health problems and/or drug and alcohol misuse), parental employment and occupation, and indicators of parental engagement (attendance at CAMHS meetings); and (c) service-related information: referring agency, interval time between referral and assessment and referral details, presenting problem and diagnosis, substance misuse, co-morbidities, episodes of self-harm and attempted suicide or suicide ideation.

Because the data was derived from administrative sources we had limited indicators of socio-economic background. However, service users’ postcodes were linked to the NI Multiple Deprivation Measure (NIMDM), a set of seven standard indicators (and associated summary) of area-level deprivation derived by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA, 2010).

Analysis

Data were analysed using Stata (Version 13). We undertook descriptive univariate analysis (proportions, means and standard deviations) and Mann–Whitney tests for non-parametric data with Z statistic and significance (P value) at < 0.05. The domains of the NI Multiple Deprivation Measures derived at ward-level were reclassified as quintiles (most to least deprived, respectively). To determine sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with transition outcomes, we used a stepwise logistic regression providing odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Ethics

This study was given a favourable opinion by the Office of Research Ethics Committee (OREC) Northern Ireland and included site specific governance approval from each of the HSC Trusts.

Results

Sample description

Three hundred and seventy-three service users (SU) were eligible for transition over the 48 month period. Table 1 shows the characteristics associated with these SUs, which included 225 females (60%) and 148 males (40%). Most (n = 197, 53%) lived with parents (who were either married or cohabiting). However, 35 (9%) were either looked after children (LAC) or cared for by people outside the immediate family; 15 (4%) were on the Child Protection Register; 34 (10%) had a Special Educational Need, and 27 (8%) were involved with a Youth Offending Team. Almost half the sample had been involved with CAMHS for 3 or more years.

Family history, deprivation and mental health

Two hundred and forty-eight service users (66.5%) were recorded as having a family history of mental illness: of these 25% (n = 62) were recorded for siblings; 13.3% (n = 33) recorded for both parents; and 44.8% (n = 104) for either the mother or the father We found no association between parental mental health and deprivation derived at neighbourhood level.

Referral to CAMHS

The median age for referral to CAMHS was 14 years (mean 14.2, SD 3.2). Males were more likely to have been referred at a younger age than females (Mann–Whitney test; z = − 3.341, P < 0.001). In addition, males spent significantly more time within CAMHS than females (Mann–Whitney: z = 3.666, P < 0.001). Seventy percent of service users (261/373) were referred by their GP; 47 (13%) through a mental health worker such as a counsellor; 39 (10%) via health services (e.g. Accident and Emergency doctor following a suicide attempt or self-harm); and the rest (6%) via their social worker or educational services, or not recorded (n = 5, 1%).

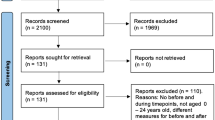

Transition pathways

Figure 1 shows a detailed breakdown of the transition pathways for the initial 373 service users—of these 104 (28%) were not referred to AMHS and, of those referred, 17 were not accepted by AMHS (7% of the referred group). For 54 of the 252 (21%), the outcome was unclear, and 14 had yet to receive an initial assessment by the end of the study period. For the 252: 184 (73%) were given appointments, of which 170 (92%) took place, though some after subsequent rearrangement. Of these, 86 (51%) were discharged after the appointment, while 14 (8%) were discharged without meeting. Of the remaining 49%, 72 remained in contact with AMHS—with 42 (50%) attending regularly, 30 (36%) attending infrequently and 13 (15%) either lost to follow-up or not recorded. Finally, of the 104 not referred, four were referred back to AMHS by their GP (as seen from the figure these do not form part of this assessment).

Twenty-five others (10%) were accepted but placed on a waiting list due to service demands. For 24 (10%) others AMHS sought further discussion with the referring clinician prior to acceptance. Service outcome was not recorded for 28 young people (11%).

Referral breach

Both date of referral to AMHS and date of first appointment at AMHS were recorded for each service user (SU). A referrals was considered breached if it took longer than the maximum 100 days target between dates of referral and first appointment with AMHS. Using this criterion, 60 (24%) referrals were classified as breached. A discussion about transfer of care from CAMHS to AMHS with service users was documented in 183 CAMHS notes (73%). In addition, a transfer-of-care discussion with the young person’s parents or carers was documented in 140 CAMHS notes (56%). For those who had a discussion recorded in CAMHS notes, the contents of these notes were examined further. Forty-seven clinicians (19%) sought consent from service users to transfer their care to AMHS. Consent to transfer care was considered to be inferred if the young person was satisfied with the conversation and did not have any concerns.

Following these criteria, consent to transfer care was inferred for 128 young people (51%). Forty-one clinicians (16%) noted that they informed the young person of why they were being transferred to AMHS. Thirty-nine clinicians (15%) recorded discussing the end of the therapeutic relationship between themselves and the young person in their notes. A transition-planning meeting was recorded in 96 cases (38%).

Transfer of care

The most common mechanism of care transfer comprised a sequential appointment - first with CAMHS, then AMHS (n = 128, 51%)—while joint appointments between CAMHS and AMHS were less prevalent (n = 46, 18%). Of the 100 cases not referred to AMHS, 28 were deemed to have completed treatment and were discharged. In addition, others were referred to voluntary sector agencies (n = 5), moved country (n = 5), or referred to Adult Intellectual Disability services (n = 3). Twenty-one cases were recorded as having refused referral. Seven did not meet AMHS criteria or lacked evidence of need for referral. In 29 cases the reasons were not recorded or had not been attending. Four cases not referred by CAMHS were later referred by their GPs and accepted by AMHS.

Meeting optimal TRACK criteria for transition

Previous research has suggested four features of an optimal transition: (1) continuity of care involving either an appointment within 3 months of the transition, or being appropriately discharged following an initial assessment if there was no need for intervention; (2) period of parallel care, involving a joint appointment with both CAMHS and AMHS; (3) transition-planning meeting, held for the young person; and (4) optimal information transfer, where three main components of information transfer were met—a referral letter, summary of CAMHS contact and CAMHS notes. Table 2 shows the use of these components in relation with the IMPACT sample: while most transferrals from CAMHS to AMHS had some level of continuity of care, only a minority had a transition-planning meeting or a period of parallel care, and none met all four criteria. Likewise, the number of cases meeting the recommended information transfer between services was small.

Factors associated with transition to AMHS

We examined the factors associated with transition from CAMHS to AMHS (Table 3). The models examined (1) personal circumstances for the child/adolescent; then, (2) household factors; and (3) selected clinical factors. Column 1 shows likelihoods associated with univariate analyses for each of the selected indicators. Males were more likely than females to be referred to adult services (odds ratio (OR) 1.71: 95% CI 1.05, 2.76), as were those classed as not in education, employment or training (NEETs) (OR 2.02: 1.07, 3.82) compared to their counterparts engaged in either working or education. Length of stay in CAMHS reduced the likelihood of transition while paternal mental illness increased the likelihood of transition (OR 5.06: 1.13, 22.44), as did maternal attendance at CAMHS meetings (OR 1.62: 1.02, 2.56). An established psychiatric diagnosis or assessment increased the likelihood of transfer. Finally, those who had been prescribed medications were more likely to be referred to AMHS. In the fully adjusted model, various factors (i.e. gender, age at first referral to CAMHS, regular meetings with CAMH services) lost significance. However, those classed as NEET were more likely (OR 3.04: 95% CI 1.34, 6.91), and those with a risk assessment or diagnosis were much more likely to have been referred to AMH services (OR 4.89: 2.45, 9.80 and OR 3.36: 1.78, 6.34, respectively). Paternal mental health also increased the likelihood of referral (OR 12.51, CI 1.39–112.5, P < 0.05). Finally, the indicators of prescription drugs taken all show excess likelihoods for referral to AMHS.

Of those 269 individuals transferred to AMHS, 74 (27.5%) remained in adult services; 100 (37.2%) were subsequently discharged; and 95 (35.3%) were disengaged from adult services. We examined the data for differences in the relationship between those remaining in adult services and those who left for some reason (i.e. combining those discharged and those who disengaged from the adult service). Compared to the lost/disengaged group, those remaining in adult services were more likely to have been prescribed either antipsychotic or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) medication (OR 1.87: 95% CI 1.08, 3.23; and OR 2.45: 1.32, 4.53, respectively); mirroring this, those with a diagnosis of ADHD were more likely to remain in adult services (OR 2.41: 1.36, 4.28). Those referred to the specific psychiatry team at transition were more likely to remain involved with AMHS (OR 3.54: 1.93, 6.51). No other factors showed significant results.

Discussion

The IMPACT study is one of the largest studies of transition between child and adolescent mental health services to adult mental health services to date. We found that a negligible minority of CAMHS referrals were rejected by adult services. Indeed, a higher number of service users formally considered for transfer to AMHS themselves refused to transfer. These findings contrast with those of the ITRACK study of transition in the Republic of Ireland where less than a third of those perceived to have on-going mental health needs were referred to adult mental health services [13] and to a lesser degree, the TRACK study [14] with 58%. Similar to the other transition studies, we found major gaps in the quality of the transition process, whereby none of the cases transferred from CAMHS to AMHS met all four criteria of an optimum transition. Few people had a transition-planning meeting or a period of parallel care. Moreover, we noted that the transfer of information between services was uncommon.

We achieved a much larger sample than expected (based on the TRACK study in England) possibly due to the cooperation of HSC Trusts, the sustained assistance of clinicians and access to transition committees—all permitting a much more rigorous case-finding process. In any case, the TRACK report [14] noted that the rates were likely to be an underestimate, dependent as they were upon clinical recall which is prone to considerable biases. Importantly though, our relatively large sample size permitted us to examine independent associations with a successful, or at least, smoother, transition to adult services.

Our main interest was the putative influence on transition outcomes. We found that the relationship of disadvantage to transitional care is unclear with no specific and dominant link to the deprivation index available to us. Thus, the referrals to CAMHS were evenly distributed between the highest and lowest quintiles of deprivation. However, the general literature on young people and health inequalities indicates that this is not unusual. For example, a recent study found that clinical referrals of young people who self-harmed were much less likely for young patients registered at the most socially deprived practices, even though incidence was considerably higher in these localities [15]. Other studies indicate that children’s use of health services may reflect health status rather than socio-economic status, indicating equity of access [16]. We found that a high proportion of children referred to CAMHS had a family history of mental illness and were living in single parent households but these were generally unrelated to the main outcomes. Moreover, while we found some social class differences in the kinds of problems for which children were referred, social class appeared not to influence other outcomes (e.g. quality of care and referral to AMHS). However, it is worth pointing out that young people not in employment, education or training (NEET) were much more likely to transfer to AMHS. The only other non-clinical factor associated with transition was paternal mental health, the explanation for which is not apparent. While parental mental illness is often associated with a challenging domestic environment for children [17], it may be that symptoms and/or behaviours associated with paternal psychiatric disorder provokes added attention from mental health services and/or increases the psychiatric needs of the young patient.

The dominating factors associated with transfer to adult services relate to diagnosis. As with previous studies those with psychotic disorders were most likely to transfer [12]. Generally, service users with disorders such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and ADHD are discharged from specialist services back to primary care and services in the UK (and internationally) lack clear transition protocols for people with ASD that facilitate continued treatment and care for a highly vulnerable group [18].

The IMPACT study was undertaken at a time when services were either already changing, or at least had begun to improve for young people following a report on CAMHS in NI [19] which had noted the presence of transition protocols in ‘most Trusts’ but lacked evidence on their implementation. Moreover, since the IMPACT study was commissioned, additional research evidence on the CAMHS–AMHS transition has been published [6, 12, 20,21,22] and has shown that services have continued to respond to these findings and to other pressures. However, the general picture emerging from the IMPACT study is that of considerable variability between service providers in how they meet the transition needs of young people [23]. Without a regional policy or protocol with regard to transition each of the five NI HSC Trusts developed their own protocols, albeit with a high degree of shared key standards [23]. However, even within individual Trusts there was no consistent or singular approach to dealing with the transition. Not all Trusts have a transition panel, and in those that do there is variation in composition, policies and procedures: one panel will review all cases that arrive at the transition stage; while another will consider only those cases considered to have complex needs. Similarly, while transition protocols exist, many clinicians have not read them or are unclear about their content. Worryingly, the barriers to effective transitional care are widespread [24] and there is limited evidence on effective service delivery models. Fragmented care, almost by definition, is inefficient [25]; the split between child and adolescent mental health services and those for adults, based on rigid age-specific criteria may allow for specialist approaches but does little to foster person-centred and need-based models of care. There is a need for interventions that minimise friction across the service boundaries and optimise engagement with care and treatment. One such project underway is MILESTONE (Managing the Link and Strengthening Transition from Child to Adult Mental Healthcare) study to determine the effectiveness of a model of managed transition in improving outcomes, compared with usual care [26].

Strengths and limitations

Our study covers a relatively homogenous population over a 4-year period, allowing a higly detailed examination of the quality of care processes and the clinical and social factors associated with transition. Due to the assistance of the Trusts and their clinical services and our intensive records search, we were able to recover more than twice the number of case notes than we anticipated. The limitations of the study relate to the usual potential challenges inherent in retrospective case-note review in that we were not able to assess the quality of the information entered. For example, in CAMHS, clinicians are often reluctant to offer a definitive diagnosis and often this is not given until the later stages of clinical involvement. Moreover, records are occasionally lost or mislaid in transit between services. We did, however, thoroughly scrutinise the electronic records for eligibility and made systematic checks on data collection and entry from the case notes. The study was further limited by having to use small area-level data on deprivation rather than more robust measures based on individual and household socio-economic status.

References

Kim HS, Munson MR, McKay M (2012) Engagement in mental health treatment among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 29(3):241–266

Harpaz-Rotem I, Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA (2004) Treatment retention among children entering a new episode of mental health care. Psychiatr Serv 55(9):1022–1028

Joe S, Lee JS (2016) Association between non-compliance with psychiatric treatment and non-psychiatric service utilization and costs in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders. BMC Psychiatry 16:444. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1156-3

Cutler RL et al (2018) Economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: a systematic review. BMJ Open 8(1):e016982. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016982

Singh SP et al (2010) Process, outcome and experience of transition from child to adult mental healthcare: multiperspective study. Br J Psychiatry 197(4):305–312

McNamara N et al (2014) Transition from child and adolescent to adult mental health services in the Republic of Ireland: an investigation of process and operational practice. Early Interv Psychiatry 3:291–297

Harpaz-Rotem I, Leslie D, Rosenheck RA (2004) Treatment retention among children entering a new episode of mental health care. Psychiatr Serv 55(9):1022–1028

Goddard M, Smith P (2001) Equity of access to health care services: theory and evidence from the UK. Soc Sci Med 53(9):1149–1162

Elgar FJ et al (2015) Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002–2010: a time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. Lancet 385(9982):2088–2095

Care Quality Commission (2017) Review of children and young people’s mental health services. Care Quality Commission, London

Garrido-Cumbrera M et al (2010) Social class inequalities in the utilization of health care and preventive services in Spain, a country with a national health system. Int J Health Serv 40(3):525–542

Paul M et al (2013) Young people’s transfers and transitions between child and adolescent and adult mental health services: the TRACK study. Br J Psychiatry 202(S54):s36–s40

McNicholas F et al (2015) Who is in the transition gap? Transition from CAMHS to AMHS in the Republic of Ireland. Ir J Psychol Med 32:61–69

Singh SP et al (2010) Transition from CAMHS to adult mental health services (TRACK): a study of service organisation, policies, process and user and carer perspectives. Report for the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme. National Institute Health Research London, HMSO

Morgan M et al (2017) Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ 359:j4351

Saxena S, Eliahoo J, Majeed A (2002) Socioeconomic and ethnic group differences in self reported health status and use of health services by children and young people in England: cross sectional study. Br Med J 325(7363):520

Fletcher RJ et al (2011) The effects of early paternal depression on children’s development. Med J Aust 195(11–12):685–689

Cheak-Zamora NC et al (2013) Disparities in transition planning for youth with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics 131(13):447–454

RQIA (2011) Independent review of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) in Northern Ireland. RQIA, Belfast

Hovish K et al (2012) Transition experiences of mental health service users, parents, and professionals in the United Kingdom: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Rehabil 35(3):251–257

Swift K, Sayal K, Hollis C (2014) ADHD and transitions to adult mental health services: a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev 40(6):775–786

Lindgren E, Soderberg S, Skar L (2013) The gap in transition between child and adolescent psychiatry and general adult psychiatry. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 26:103–109

Leavey G et al (2018) Improving mental health pathways and care for adolescents in transition to adult services in Northern Ireland (IMPACT). Northern Ireland Public Health Agency, Belfast

Paul M et al (2015) Transition to adult services for young people with mental health needs: a systematic review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 20(3):436–457

Stange KC (2009) The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Ann Fam Med 7(2):100–103

Singh SP et al (2017) Protocol for a cohort study of adolescent mental health service users with a nested cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical and cost- effectiveness of managed transition in improving transitions from child to adult mental health services (the MILESTONE study). BMJ Open 7(10):e016055. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016055

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the R&D Division of the Public Health Agency Northern Ireland (Grant no. COM/4662/12 Bamford). We are grateful for their support and that of the participating NHS Health and Social Care Trusts and the Northern Ireland Clinical Research Network-Mental Health. We also thank the Royal College of Psychiatry NI for their assistance and that of the College Trainees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, I can state that there are no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Leavey, G., McGrellis, S., Forbes, T. et al. Improving mental health pathways and care for adolescents in transition to adult services (IMPACT): a retrospective case note review of social and clinical determinants of transition. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54, 955–963 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01684-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01684-z