Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

It is not clear how small tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib mesilate, protect against diabetes and beta cell death. The aim of this study was to determine whether imatinib, as compared with the non-cAbl-inhibitor sunitinib, affects pro-survival signalling events in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway.

Methods

Human EndoC-βH1 cells, murine beta TC-6 cells and human pancreatic islets were used for immunoblot analysis of insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1, Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3] plasma membrane concentrations were assessed in EndoC-βH1 and MIN6 cells using evanescent wave microscopy. Src homology 2-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase 2 (SHIP2) tyrosine phosphorylation and phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) serine phosphorylation, as well as c-Abl co-localisation with SHIP2, were studied in HEK293 and EndoC-βH1 cells by immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis. Gene expression was assessed using RT-PCR. Cell viability was measured using vital staining.

Results

Imatinib stimulated ERK(thr202/tyr204) phosphorylation in a c-Abl-dependent manner. Imatinib, but not sunitinib, also stimulated IRS-1(tyr612), Akt(ser473) and Akt(thr308) phosphorylation. This effect was paralleled by oscillatory bursts in plasma membrane PI(3,4,5)P3 levels. Wortmannin induced a decrease in PI(3,4,5)P3 levels, which was slower in imatinib-treated cells than in control cells, indicating an effect on PI(3,4,5)P3-degrading enzymes. In line with this, imatinib decreased the phosphorylation of SHIP2 but not of PTEN. c-Abl co-immunoprecipitated with SHIP2 and its binding to SHIP2 was largely reduced by imatinib but not by sunitinib. Imatinib increased total β-catenin levels and cell viability, whereas sunitinib exerted negative effects on cell viability.

Conclusions/interpretation

Imatinib inhibition of c-Abl in beta cells decreases SHIP2 activity, which results in enhanced signalling downstream of PI3 kinase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Imatinib mesilate is a 2-phenylaminopyrimidine-based ATP-competitive inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase family [1] and also has an inhibitory action at the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), transmembrane stem-cell factor receptor (c-Kit) and discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1). It is currently used to treat chronic myeloid leukaemia, a disease associated with the BCR–ABL oncogene and also gastrointestinal stromal tumours that result from c-KIT (also known as KIT) mutations [2]. Besides its pioneering role in oncology, imatinib has also been observed to counteract diabetes in patients [3–9] and in animal models for both type 1 and type 2 diabetes [10–15]. First, imatinib improves insulin sensitivity in individuals with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes and in corresponding animal models [5, 8, 10]. Second, imatinib enhances beta cell survival in response to toxins and pro-inflammatory cytokines, possibly via inhibition of the pro-apoptotic tyrosine kinase cellular Abl (c-Abl) [13, 14]. Third, imatinib probably modulates the immune system of NOD mice so that beta cells are better tolerated and diabetes is both prevented and reversed [13, 15]. This third pathway may include imatinib-mediated inactivation of c-Kit and DDR1 [16, 17].

Sunitinib is a multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which acts at PDGFRα, PDGFRβ and c-Kit, and also inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other tyrosine kinases [18]. Similarly to imatinib, sunitinib counteracts type 2 diabetes [7, 19] and diabetes in NOD mice [15], possibly via inhibition at the PDGFR leading to lowered insulin resistance and/or modulation of the immune system [15]. The effects of sunitinib on beta cell signalling and apoptosis rates have, however, not been studied.

Insulin signalling is required for beta cell survival, proliferation and function [20]. Insulin promotes insulin receptor autophosphorylation and insulin receptor substrate (IRS) tyrosine phosphorylation. This is followed by IRS-mediated activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and the synthesis of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3]. PI(3,4,5)P3 recruits and activates phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) and Akt/PKB, which initiates increased glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation in fat and skeletal muscle and proliferation, survival and improved insulin production in beta cells [20]. However, PI3K-induced signalling is antagonised by PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10) and SHIP2 (Src homology 2-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase 2) [21, 22]. PTEN removes the 3′-phosphate from PI(3,4,5)P3 and phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate [PI(3,4)P2] thereby generating phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate. As a 5′-phosphatase, SHIP2 dephosphorylates PI(3,4,5)P3 into PI(3,4)P2. Enhanced activity of PTEN and SHIP2 inhibits insulin signalling and probably accelerates the development of type 2 diabetes. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that Ship2 +/− (also known as Inppl1 +/−) mice display improved insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance due to increased glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis in skeletal muscles [23]. Furthermore, increased expression of Pten was observed in islets of high-fat-diet fed and db/db mice, and deletion of Pten in pancreatic beta cells was beneficial for maintaining beta cell mass, function and PI3K signalling [24].

Akt controls levels and activity of β-catenin by phosphorylating and inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) [25]. When not phosphorylated by Akt, GSK3 phosphorylates β-catenin at positions ser33, ser37 and thr41, which leads to β-catenin ubiquitination and degradation. Thus, Akt activation is known to be associated with increased β-catenin stability and activity. In addition, β-catenin can be phosphorylated at sites other than ser33, ser37 and thr41, in which case nuclear translocation may occur. For example, protein kinase A (PKA)-induced phosphorylation of β-catenin at ser675 results in β-catenin accumulation in the nucleus [26]. β-Catenin is found both in adherens junctions (where it binds cadherins and establishes a link to the cytoskeleton) and in the nucleus (where it binds T cell factor and lymphoid enhancer factor transcription factors and promotes transcription of pro-survival genes). In beta cells, it has been shown that Akt activation results in increased β-catenin activity [27], that β-catenin activity protects against cytokine- and thapsigargin-induced cell death [28] and that lack of β-catenin in early life is related to severe dysregulation of glucose homeostasis [29].

In cells other than beta cells imatinib has been observed to affect insulin signalling, probably via inhibition of c-Abl [30]. Thus, it is possible that imatinib promotes beta cell survival and improved function via modulation of IRS-1-, PI3K-, Akt-, ERK- and β-catenin signalling, under basal conditions, during stimulation with insulin or under stressful conditions. The aim of this study was therefore to compare the effects of the c-Abl inhibitor imatinib with those of the non-c-Abl inhibitor sunitinib on beta cell signalling events, and to correlate signalling events to beta cell survival.

Methods

Materials

Imatinib mesilate was generously provided by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). Sunitinib was from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). Diazoxide, insulin and LY294002 were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Lipofectamine 2000 was obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). Dipotassium bisperoxo(5-hydroxypyridine-2-carboxyl)oxovanadate (bpV(HOpic) and diethylenetriamine nonoate (DETA/NO) were from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Cell culture

Human EndoC-βH1 cells were cultured in extracellular matrix (ECM)/fibronectin-coated plates in low-glucose DMEM with supplements as previously described [31]. Murine beta TC-6 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% (vol./vol.) FBS (Sigma), l-glutamine, benzylpenicillin and streptomycin (working solution). Human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells were grown in DMEM medium (Life Technologies) with 10% (vol./vol.) FBS, l-glutamine, benzylpenicillin and streptomycin. For MIN6 cell culture, 70 μmol/l β-mercaptoethanol and 15% FBS were added to the medium. Human pancreatic islets were cultured in CMRL1066 media containing the same supplements as the working solution. Permission to obtain pancreatic islet tissue from the Nordic Network for Clinical Islet Transplantation was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee (Regionala etikprövningsnämnden, Uppsala) in Uppsala, Sweden.

For knock-down of c-Abl, EndoC-βH1 cells were incubated overnight with Lipofectamine 2000 complexed with either control siRNA (Sigma) or c-Abl-specific siRNA (30 nmol/l) (Sigma) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Liposome/siRNA complexes were removed the next day by changing the medium. Cells were analysed by immunoblotting 2 days after start of the transfection procedure.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) sample buffer, boiled for 5 min and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto a Hybond-P membrane (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). Membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies: 4G10 phosphotyrosine and IRS-1(tyr612) (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), phospho-β-catenin(ser675), phospho-PTEN(ser380), SHIP2, phospho-SHIP2(tyr1135), phospho-ERK(thr202/tyr204), phospho-Akt(thr308), phospho-Akt(ser473) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), total ERK (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), total β-catenin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), PTEN and c-Abl (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany and Santa Cruz). Bound antibodies were removed from filters by incubating for 40 min at 55°C in 2% (wt/vol.) SDS, 100 mmol/l Tris, pH 6.8, and 0.1 mol/l β-mercaptoethanol. The immunodetection was performed as described for the ECL immunoblotting detection system (GE healthcare) and using the Kodak Image station 4000MM. The band intensity was quantified by densitometric scanning using CareStream Digital Science ID software.

Immunoprecipitation

After treatment with drugs, cells were washed with cold PBS three times, scraped and centrifuged. The cell pellets were collected and lysed for 30 min in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with 1 mmol/l phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. After centrifugation, supernatant fractions were supplemented with PTEN (A2B1, Santa Cruz) or SHIP2 (C76A7, Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies and kept on ice for 1 h. PTEN and SHIP2 proteins were then precipitated with Protein G- or Protein A sepharose. The samples were boiled for 5 min in SDS sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE.

Plasma membrane PI(3,4,5)P3 measurements

Human general receptor for phosphoinositides 1 fused to a tandem construct with four molecules of green fluorescent protein (GFP4–GRP1) was used as a translocation biosensor for the plasma membrane PI(3,4,5)P3 concentration [32]. MIN6 or EndoC-βH1 cells were transiently transfected while being seeded onto 25 mm glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine or ECM/fibronectin. For each coverslip, ∼0.2 million cells were suspended in 100 μl Optimem medium containing 0.5 μl Lipofectamine 2000 with 0.2 μg plasmid DNA, and plated onto the glass. After 3 h, 3 ml complete cell culture medium was added and cells were cultured for additional 16–24 h. The plasma membrane concentration of GFP4–GRP1 was recorded using evanescent wave microscopy as previously described [33]. GFP fluorescence was detected at 525/25 nm (centre wavelength/half-bandwidth, nm) by an Orca-ER camera or a back-illuminated DU-897 EMCCD camera under MetaFluor software control (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Images were acquired every 5 s and the fluorescence intensity from individual cells was logged over time using MetaFluor and expressed relative to the initial fluorescence (F/F0). Decay constants were extracted from exponential curve fittings, which were performed with Igor Pro 6 software (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). Relative fluorescence values were normalised to allow creation of an average trace. Many experiments were performed with a simultaneously expressed inert red fluorescent protein (tdimer2-CAAX) to ensure that the various cell treatments did not induce non-specific changes in the fluorescence signal.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

The total RNA was extracted using the Ultraspec RNA isolation system reagent (Biotecx, Houston, TX, USA) according to the supplier’s instructions. cDNA was synthesised using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase kit (Life Technologies) and oligo-dT-primers according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Real-time RT-PCR

Semi-quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the Lightcycler instrument (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and the SYBR Green JumpStart Taq Ready Mix (Sigma-Aldrich). Sequences of primers used can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author. The relative level of cAMP responsive element modulator (CREM) and thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) was calculated using the formula: \( {2^{{^{{\mathrm{crossing}\;\mathrm{point}\mathrm{G}6\mathrm{PDH}-\mathrm{crossing}\;\mathrm{point}\;\mathrm{CREM},\;\mathrm{TXNIP}}}}}} \).

Evaluation of cell viability

Beta TC-6 cells were cultured in 96-well plates and were treated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) or sunitinib (1 μmol/l and 10 μmol/l) for 6 h. The cells were then incubated with the cell death agents IL-1β (20 ng/ml), IFN-γ (20 ng/ml), DETA/NO (1 mmol/l) or hydrogen peroxide (0.1 mmol/l) for 24 h. Cell viability was measured by staining cells with propidium iodide (30 μmol/l) and bisbenzimide (10 μmol/l) for 10 min at 37°C. The medium was replaced with PBS and the red and blue fluorescence was detected using the Kodak 4000MM Image Station (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA). The ratio of red to blue was taken as a relative measure of cell death (necrosis and late apoptosis) and was quantified using CareStream Digital Science ID 5.0 software (Carestream Health).

Statistics

Treatments and experimental procedures were performed under paired conditions (all samples from each experiment were generated and analysed in parallel) and statistical significances were obtained by comparison with the corresponding control using Student’s paired t test.

Results

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on Akt, ERK and IRS-1 phosphorylation

Imatinib has been reported to affect insulin receptor signalling in non-beta cells [30]. To establish whether imatinib also controls receptor tyrosine kinase signalling in beta cells, we studied the effects of imatinib on ERK phosphorylation in human EndoC-βH1 cells. Exposure of cells to 2 or 10 μmol/l of imatinib for 20 min significantly increased ERK phosphorylation and the increase was even stronger after 6 h (Fig. 1). Treatment of cells with c-Abl-specific siRNA resulted in a 59% decrease in c-Abl protein levels (control, 1.07 ± 0.13; ABL1 siRNA, 0.45 ± 0.12; p < 0.01), when normalised to total ERK levels.

Effect of imatinib and c-Abl knock-down on ERK phosphorylation in EndoC-βH1 cells. EndoC-βH1 cells were treated with control or c-Abl-specific siRNA. Two days later cells were incubated for 20 min or 6 h with 0, 2 or 10 μmol/l of imatinib. ERK(thr202/tyr204) phosphorylation was then analysed by immunoblotting. Results from immunoblots were quantified using densitometry. Phospho-ERK (p-ERK) bands were expressed per total ERK band intensity obtained from the same filters. Results are means ± SEM for four observations. *p < 0.05 vs corresponding control (no imatinib and control siRNA) (Student’s paired t test)

In c-Abl knock-down cells ERK phosphorylation was elevated at basal conditions, and no further increase in response to imatinib was observed (Fig. 1). We also probed for Akt and IRS-1 phosphorylation in EndoC-βH1 cells, but were unsuccessful in obtaining quantifiable signals. Instead, we observed clear phospho-Akt and phospho-IRS-1 signals when using murine beta TC-6 cells. A 6 h period was chosen for the exposure of EndoC-βH1 cells to imatinib as this gave a stronger effect than exposure for 20 min (Fig. 1). At basal conditions imatinib enhanced beta TC-6 IRS-1(tyr612), Akt(thr308), Akt(ser473) and ERK(thr202/tyr204) phosphorylation (Fig. 2a–d) whereas sunitinib stimulated only the phosphorylation of ERK(thr202/tyr204) (Fig. 2c). Imatinib and sunitinib attenuated the decrease of ERK(thr202/tyr204) phosphorylation during nitrosative stress (Fig. 2c). Imatinib and sunitinib enhanced Akt(ser473) and ERK(thr202/tyr204) phosphorylation in the presence of exogenous insulin (Fig. 2a, c). BpV(HOpic) increased Akt(ser473) phosphorylation in insulin-stimulated cells, but did not affect ERK or IRS-1 phosphorylation (Fig. 2a–d).

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on Akt, ERK and IRS-1 phosphorylation in beta TC-6 cells. Beta TC-6 cells were pre-incubated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) or sunitinib (1 μmol/l) for 6 h or with the PTEN inhibitor bpV(HOpic) (PTEN inh.; 100 nmol/l) for 60 min in serum-free medium. To some of the groups DETA/NO (1 mmol/l) or insulin (20 nmol/l) was added after 6 h and the incubation was continued for 60 min. The cells were then used for immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific to (a) Akt(thr308), (b) Akt(ser473), (c) ERK(thr202/tyr204) or (d) IRS-1(tyr612). Results from immunoblots were quantified using densitometry. Band intensity was quantified and expressed per total protein loading (Amido Black staining). Results are means ± SEM for three to six observations. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs corresponding control (Student’s paired t test). Imatinib-, sunitinib- or PTEN-inhibitor-treated cells were only compared with cells not treated with imatinib, sunitinib or PTEN inhibitor, but receiving the same treatment (with insulin, DETA/NO or no addition)

Similarly to beta TC-6 cells, human islets responded to imatinib with increased Akt(ser473), ERK(thr202/tyr204) and IRS-1(tyr612) phosphorylation (Fig. 3). When combined with insulin, imatinib did not further increase Akt, ERK or IRS-1 phosphorylation (Fig. 3).

Effect of imatinib on Akt, ERK and IRS-1 phosphorylation in human islets. Human islets were pre-incubated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) for 6 h in serum-free medium. To some of the groups insulin (20 nmol/l) was added after the 6 h and the incubation was continued for 60 min. The islets were then used for immunoblot analysis using (a) Akt(ser473), (b) ERK(thr202/tyr204) or (c) IRS-1(tyr612) specific antibodies. Results from immunoblots were quantified using densitometry. Results are means ± SEM for five observations. *p < 0.05 vs corresponding control (Student’s paired t test)

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on plasma membrane PI(3,4,5)P3 levels

To monitor changes in the membrane concentration of PI(3,4,5)P3 in real time we used evanescent wave microscopy and a GFP-tagged PI(3,4,5)P3-binding protein domain. MIN6 cells were used because experimental procedures have been optimised for this particular cell line [32]. In unstimulated MIN6 cells exposed to 3 mmol/l glucose the PTEN inhibitor bpV(HOpic) induced a gradual increase in the level of PI(3,4,5)P3, which was rapidly reversed by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Fig. 4a). Imatinib evoked oscillatory increases in the PI(3,4,5)P3 levels, which appeared at an interval of 3–4 min (Fig. 4b), but had no effect on the fluorescence of a simultaneously expressed, inert red fluorescent protein (tdimer2-CAAX; not shown). These bursts were of high amplitude and were observed in a majority of the analysed cells (29 out of 48 individual cells in three independent experiments). The PI(3,4,5)P3 oscillations were not affected by the ATP-sensitive potassium-channel opener diazoxide (Fig. 4b). Sunitinib did not affect PI(3,4,5)P3 levels, but addition of insulin promoted an immediate increase in PI(3,4,5)P3 when added after the sunitinib exposure period (Fig. 4c). Oscillatory PI(3,4,5)P3 changes upon imatinib addition were also observed in the human EndoC-βH1 cells, although they occurred less frequently (nine out of 32 individual cells in ten independent experiments) (Fig. 4d). Imatinib did not induce changes in tdimer2-CAAX fluorescence (not shown). Insulin-stimulated PI(3,4,5)P3 production in EndoC-βH1 cells was completely reversed after PI3K inhibition with wortmannin (Fig. 4e). However, the decay was significantly slower in the presence of imatinib than in control (28.5 ± 2.4 s half-life with imatinib vs 15.5 ± 2.2 s in control, p = 0.0034 using Student’s two-sample t test), indicating that imatinib might affect PI(3,4,5)P3 levels by modulating degradation of the lipid.

Evanescent wave microscopy recordings of GFP4–GRP1 translocation (i.e. PI(3,4,5)P3 plasma membrane levels) in MIN6 or EndoC-βH1 cells. (a) TIRF images of GFP4–GRP1-expressing MIN6 beta cells under basal conditions and in the presence of the PTEN inhibitor bpV(HOpic) (bpV; 100 nmol/l). The graph shows a representative single-cell recording of plasma membrane fluorescence intensity changes over time in the presence of the PTEN inhibitor bpV(HOpic) and the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (100 μmol/l). (b, c) Effect of imatinib (10 μmol/l) and sunitinib (1 μmol/l), respectively, on plasma membrane PI(3,4,5)P3 levels in MIN6 beta cells. The response to imatinib is not disturbed by diazoxide (250 μmol/l) (b). Insulin (100 nmol/l) serves as positive control (c). (d) TIRF microscopy recording of an individual GFP4–GRP1-expressing EndoC-βH1 cell in response to imatinib (10 μmol/l) and insulin (100 nmol/l). (e) Effect of imatinib (10 μmol/l) on the breakdown of PI(3,4,5)P3 after inhibition of PI3K with wortmannin (300 nmol/l) in the presence of insulin (100 nmol/l). Results are means ± SEM for 13 and six recordings of individual EndoC-βH1 cells in the presence (black line) and absence (grey line) of imatinib, respectively. All other traces are representative recordings from individual cells, from three to ten independent experiments in which at least 30 cells were analysed

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on SHIP2 tyrosine phosphorylation

A lowered decay rate of PI(3,4,5)P3 in the presence of wortmannin may result from a lowered SHIP2 activity. Tyrosine phosphorylation has been demonstrated to increase SHIP2 enzymatic activity [34]. We used HEK293T cells to study the effects of imatinib and sunitinib on SHIP2 tyrosine phosphorylation because: (1) a commercially available antibody that successfully precipitates SHIP2 is only available for human cells and (2) it is hard to generate sufficient numbers of EndoC-βH1 cells for immunoprecipitation experiments. SHIP2 was successfully precipitated from the HEK293T cells and neither imatinib nor sunitinib affected levels of precipitated SHIP2 (Fig. 5a, b). However, when probing the membranes with the 4G10 antibody, a 60% decrease in SHIP2 tyrosine phosphorylation was observed in response to exposure to imatinib for 20 min (Fig. 5a). In contrast, sunitinib did not affect the tyrosine phosphorylation of SHIP2 (Fig. 5b). To corroborate these immunoprecipitation results, we analysed SHIP2 tyrosine phosphorylation at position 1,135 in EndoC-βH1 cells exposed to imatinib and sunitinib for different periods. We observed that imatinib, but not sunitinib, promoted a decreased SHIP2(tyr1135) phosphorylation (Fig. 5c).

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on tyrosine phosphorylation of SHIP2, SHIP2–c-Abl interaction and PTEN serine phosphorylation. HEK 293T cells were either left untreated or treated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) (a) or sunitinib (10 μmol/l) (b) for 20, 60 or 180 min. Cells were solubilised and proteins were immunoprecipitated with SHIP2 antibody. SHIP2 tyrosine phosphorylation was analysed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine and SHIP2 antibodies. Results from immunoblots were quantified using densitometry. Values of phosphorylated protein bands were related to those of SHIP2 bands. Data are presented as means ± SEM for three or four experiments. *p < 0.05 vs corresponding control (Student’s paired t test). (c) EndoC-βH1 cells were treated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) or sunitinib (1 μmol/l) for 20, 60 or 180 min. Cells were solubilised and proteins were analysed by immunoblotting using phospho-SHIP2(tyr1135) and total SHIP2 antibodies. Results are means ± SEM for four observations. *p < 0.05 vs corresponding control (Student’s paired t test). (d, e) HEK293T cells were either left untreated or were treated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) (d) or sunitinib (10 μmol/l) (e) for 20, 60 or 180 min. Cells were solubilised and proteins were immunoprecipitated with a SHIP2 antibody. c-Abl co-immunoprecipitation was detected with a c-Abl antibody. One representative blot out of three experiments is shown. (f, g) Beta TC-6 cells were either left untreated or were treated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) (f) or sunitinib (10 μmol/l) (g) for 20, 60 or 180 min. Cells were solubilised and proteins were immunoprecipitated with a PTEN antibody. PTEN phosphorylation was analysed by immunoblotting with phospho(Ser380)-PTEN and PTEN antibodies. Values of phosphorylated protein bands were related to those of PTEN bands. Data are presented as means ± SEM of three of four experiments. *p < 0.05 vs corresponding control (Student’s paired t test). IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on c-Abl co-immunoprecipitation with SHIP2

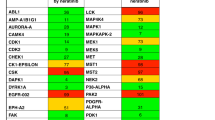

To determine whether c-Abl co-immunoprecipitates with SHIP2, SHIP2 was immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells exposed to imatinib and sunitinib for different time periods. We observed that c-Abl co-immunoprecipitated with SHIP2 and that its binding to SHIP2 was largely reduced by imatinib treatment for 20 min (Fig. 5d). However, sunitinib had no obvious effect on c-Abl binding to SHIP2 (Fig. 5e). Neither could we observe c-Abl co-immunoprecipitation with PTEN (results not shown). Although we cannot exclude the activity of other tyrosine kinases, the imatinib-sensitive interaction between SHIP2 and c-Abl indicates that SHIP2 might be tyrosine phosphorylated directly by c-Abl. This prompted us to look for putative tyrosine phosphorylation sites for c-Abl in SHIP2. Using the KinasePhos 2.0 program [35], three sites for c-Abl with high support vector machine (SVM) scores in human SHIP2 were found: position 102 (sequence LIGLYAQPN, score 0.54361); position 610 (sequence GDLNYRLDM, score 0.608056); position 777 (sequence CLEEYKKSF, score 0.5). Of these sites, position 102 may be particularly important because it is located in the SH2 domain of the SHIP2 protein and it has been reported that the SH2 domain exerts an auto-inhibitory function when not phosphorylated on tyrosine residues [34].

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on ser380 phosphorylation of PTEN in beta TC-6 cells

PI(3,4,5)P3 levels also depend on the activity of PTEN. Phosphorylation at position ser380 is known to affect the stability and activity of PTEN [36]. To study the effects of imatinib and sunitinib on serine phosphorylation of PTEN, beta TC-6 cells were treated with imatinib or sunitinib and PTEN phosphorylation was analysed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. PTEN was successfully immunoprecipitated and the levels of the protein were not affected by imatinib or sunitinib (Fig. 5f, g). Ser380 phosphorylation of PTEN was not affected by imatinib (Fig. 5f). Sunitinib, however, tended to increase ser380 phosphorylation after 20 min, but the effect did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5g).

Imatinib increased total β-catenin protein levels and Crem mRNA

We next investigated whether the Akt downstream target β-catenin was affected by imatinib. Imatinib treatment for 1 and 6 h increased the levels of total β-catenin in MIN6 cells cultured with (results not shown) or without serum (Fig. 6a). Although insulin treatment did not affect β-catenin levels significantly, there was a trend to increased β-catenin levels in cells stimulated with insulin for 15 min (Fig. 6a). Insulin did not further increase β-catenin levels in cells exposed to imatinib (Fig. 6a). Neither imatinib nor insulin treatment induced β-catenin ser675 phosphorylation at any of the culture conditions used (Fig. 6a). Rather, phosphorylated ser675-β-catenin levels were decreased in response to imatinib (at 1 and 6 h) when expressed per total β-catenin (results not shown).

Imatinib increases β-catenin protein levels in MIN6 cells and human islets. (a) MIN6 cells cultured without serum were either left untreated or were treated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) for 1 or 6 h. In indicated groups the cells were stimulated with insulin (100 nmol/l) during the last 15 min. The cells were then analysed by immunoblotting using by total β-catenin and phospho-β-catenin(Ser675) antibodies. Results from immunoblots were quantified using densitometry. Total β-catenin and phospho-β-catenin bands were related to total protein loading (amido black staining). Data are presented as means ± SEM of three individual observations. *p < 0.05 vs untreated group (Student’s t test). (b) Human pancreatic islets cells were left untreated (control) or were treated with imatinib (10 μmol/l, 1 or 6 h) in serum-free medium. Data are presented as means ± SEM for four individual observations. *p < 0.05 vs untreated group vs corresponding control (Student’s paired t test)

The finding that imatinib increased total β-catenin levels in MIN6 cells prompted us to investigate whether this also occurred in human islet cells. No significant effect could be observed on ser675 phosphorylation; however, human islets treated with imatinib for 6 h contained 58% more β-catenin than untreated control islets (Fig. 6b). Short-term exposure (1 h) did not affect total β-catenin expression (Fig. 6b). These results indicate that imatinib stabilises β-catenin without affecting ser675 phosphorylation.

To further explore whether imatinib stimulates β-catenin signalling, Crem and Txnip mRNA levels were measured. It has been reported that glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 increases Crem and decreases Txnip mRNA levels in insulin-producing cells [37]. In line with this, in the current study we observed that GLP-1 treatment (6 h) induced Crem mRNA expression in MIN6 cells (Fig. 7). Moreover, imatinib treatment (6 h) also induced Crem mRNA expression (Fig. 7), whereas insulin treatment (6 h) only evoked a non-significant increase in Crem mRNA levels. GLP-1, imatinib and insulin had no effect on Txnip mRNA levels (Fig. 7).

Effect of GLP1, insulin and imatinib on relative Crem and Txnip mRNA levels in MIN6 cells. MIN6 cells were treated with GLP-1 (100 nmol/l), insulin (100 nmol/l) and imatinib (10 μmol/l) for 6 h in serum-free medium. Crem (black bars) and Txnip (grey bars) mRNA levels were semi-quantified by real-time RT-PCR using GAPDH as housekeeping gene. Results are presented as means ± SEM for three to five individual observations. *p < 0.05 vs corresponding control (Student’s paired t test)

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on beta TC-6 cell viability in response to hydrogen peroxide, cytokines and DETA/NO

Finally, we wanted to correlate the effects of imatinib and sunitinib on signalling events with cell viability. Cytokines, DETA/NO and hydrogen peroxide enhanced cell death rates by 30%, 60% and 80%, respectively (Fig. 8). Imatinib increased survival at basal conditions by 26% and protected beta TC-6 cells against cytokines and DETA/NO to a similar degree (Fig. 8). Sunitinib did not protect against cell death but tended to increase cell death at a concentration of 1 μmol/l (Fig. 8). At 10 μmol/l, sunitinib dramatically increased beta TC-6 cell death by itself (Fig. 8).

Effect of imatinib and sunitinib on beta TC-6 cell viability. Beta TC-6 cells were either left untreated or were treated with imatinib (10 μmol/l) or sunitinib (1 μmol/l [1] or 10 μmol/l [10]) for 6 h, and then incubated with cytokines (IL-1β 20 pg/ml, IFN-γ 20 pg/ml), DETA/NO (1 mmol/l) or hydrogen peroxide (0.1 mmol/l) for 24 h. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide (PI; 30 μmol/l) and bisbenzimide (10 μmol/l) for 10 min at 37°C. Then the medium was replaced with PBS and the red and blue fluorescence was detected with the Kodak 4000MM image station. Results were quantified using densitometry and the ratio of red to blue was taken as a relative measure of cell death. Values are means ± SEM from three to five experiments. *p < 0.05 vs corresponding control (Student’s paired t test)

Discussion

We observed that imatinib increased the activity of the IRS-1-, PI3K-, ERK-, Akt- and β-catenin-signalling pathway, and that this was accompanied by an improved survival at basal conditions and in response to cytokines and the nitric oxide donor DETA/NO. Increased tyrosine kinase signalling was demonstrated not only in rodent cell lines but also in human islets and the recently generated human beta cell line EndoH-βC1 [31], indicating that the imatinib-induced effects are not species or cell-line specific. In cell types other than insulin-producing cells c-Abl has been demonstrated to negatively regulate receptor tyrosine kinase signalling. Both trk A, the receptor for nerve growth factor, and Met, the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor, associate with c-Abl, leading to attenuated receptor signalling [37–40]. Since imatinib, but not sunitinib, enhanced IRS-1 phosphorylation in insulin-producing cells, it is likely that c-Abl also dampens receptor tyrosine kinase signalling at basal conditions in beta cells. This is further supported by our finding that knock-down of c-Abl in EndoH-βC1 cells resulted in increased basal ERK phosphorylation and a blunted imatinib effect. Surprisingly, sunitinib, which does not inhibit c-Abl, also increased ERK phosphorylation but this effect may be explained by compensatory tyrosine kinase activation as demonstrated in adrenocortical carcinoma cells [41].

The fluctuations in plasma membrane PI(3,4,5)P3 concentrations observed in imatinib-treated cells resembled those induced by stimulatory glucose concentrations [42]. The glucose-induced PI(3,4,5)P3 elevations are secondary to insulin secretion and autocrine activation of insulin receptors and PI3K. However, we consider it unlikely that the effects of imatinib were derived from a direct action on the insulin secretion process. In a previous study imatinib did not influence insulin secretion from human and rat islets during short-term (1 h) or long-term (24 h) exposure to imatinib [13]. Moreover, diazoxide, which hyperpolarises the plasma membrane and suppresses insulin secretion by opening ATP-sensitive K+ channels, did not affect imatinib-induced PI(3,4,5)P3 levels. This observation may indicate that imatinib raises PI(3,4,5)P3 by different mechanisms from glucose and insulin. Besides PI3K, PI(3,4,5)P3 levels are also controlled by the PI(3,4,5)P3 phosphatases PTEN and SHIP2. It has been reported that the c-Abl protein interacts directly with SHIP2 via its SH3 domain [43]. Thus, imatinib could modulate PI(3,4,5)P3 levels by a different mechanism from glucose and insulin by not only activating PI3K but also by controlling SHIP2 activity. Indeed, we observed that imatinib induced lowering of the PI(3,4,5)P3 decay rate in cells with inhibited PI3K activity, indicating that imatinib induced the inhibition of a PI(3,4,5)P3 specific phosphatase. In addition, we found that c-Abl co-immunoprecipitated with SHIP2 and that imatinib counteracted both SHIP2 tyrosine phosphorylation and SHIP2 binding to c-Abl. Because tyrosine phosphorylation augments the phosphatase activity of SHIP2 [34], these findings indicate that c-Abl binds to, and phosphorylates, SHIP2 leading to increased SHIP2 activity. In this context it is worth noting that SHIP2 inhibition in INS1E cells has been observed to stimulate Akt, GSK3 and ERK phosphorylation and to promote increased cell proliferation [44]. A suppressive effect of imatinib on SHIP2 activity may not only be pertinent to the function of the insulin-producing cell, but also to insulin-sensitive peripheral cells, as inhibition of SHIP2 in adipocytes has been observed to ameliorate insulin resistance [45]. Thus, imatinib-induced insulin sensitivity may arise not only from inhibition of excessive PDGFR activity [5, 8, 10], but also from inhibition of c-Abl-induced SHIP2 activation.

PTEN phosphorylation at position ser380 was not affected by imatinib, but was possibly increased by sunitinib. Ser380 phosphorylation is considered a marker for PTEN relocalisation from the plasma membrane to some other internal site with less enzymatic activity [46]. However, since sunitinib did not affect PI(3,4,5)P3 plasma membrane concentration, the importance of the sunitinib-induced trend to increase ser380 phosphorylation remains unclear.

β-Catenin is an important mediator of Wnt and Akt signalling, and increased β-catenin levels have been shown to confer anti-apoptotic and proliferative effects in various cell types. We observed that a 6 h incubation with imatinib increased β-catenin levels in both MIN6 cells and primary human islets. This stabilisation was not due to phosphorylation of β-catenin at position ser675. This particular phosphorylation event is executed by PKA and mediates β-catenin nuclear translocation and activation [26]. Rather, is likely that β-catenin levels rise in response to Akt-induced GSK3 phosphorylation and inactivation, as observed in previous studies [25, 27]. The augmented β-catenin levels were likely to promote significant alterations in gene expression in view of the observed increase in CREM mRNA, a β-catenin/TCF7L2 target gene [47].

In summary, our results suggest that imatinib, by relieving beta cells from c-Abl-mediated suppression of tyrosine kinase receptor signalling and activation of SHIP2, stimulates events that promote beta cell survival. This is in contrast to sunitinib, which exerts negative effects on beta cell survival. This might indicate that although sunitinib protects against diabetes in NOD mice [15], it might be a less suitable candidate for type 1 diabetes prevention trials, which have recently been proposed for imatinib [48–50]. The use of imatinib in type 2 diabetes trials is not a realistic option considering the side-effect profile and high cost of this drug. Nevertheless, an improved knowledge of its mechanisms of action will hopefully help us understand how type 2 diabetes develops and how to better treat the disease.

Abbreviations

- bpV(HOpic):

-

Dipotassium bisperoxo(5-hydroxypyridine-2-carboxyl)oxovanadate

- CML:

-

Chronic myeloid leukaemia

- CREM:

-

cAMP responsive element modulator

- DDR1:

-

Discoidin domain receptor 1

- DETA/NO:

-

Diethylenetriamine nonoate

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

- ERK:

-

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GFP:

-

Green fluorescent protein

- GIST:

-

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- GRP1:

-

General receptor for phosphoinositides 1

- GSK3:

-

Glycogen synthase kinase 3

- IRS:

-

Insulin receptor substrate

- c-Kit:

-

Stem-cell factor receptor

- PDGFR:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PDK:

-

Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase

- PI3K:

-

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PI(3,4,5)P3 :

-

Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate

- PI(3,4)P2 :

-

Phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate

- PKA:

-

Protein kinase A

- PTEN:

-

Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10

- SHIP2:

-

Src homology 2-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase 2

- TIRF:

-

Total internal reflection fluorescence

- TXNIP:

-

Thioredoxin-interacting protein

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Maekawa T, Ashihara E, Kimura S (2007) The Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib and promising new agents against Philadelphia chromosome positive leukemias. Review. Int J Clin Oncol 12:327–340

David T, Nicholas W, Tyler J et al (2001) STI571 inactivation of the gastrointestinal stromal tumor c-KIT oncoprotein: biological and clinical implications. Oncogene 20:5054–5058

Breccia M, Muscaritoli M, Aversa Z, Mandelli F, Alimena G (2004) Imatinib mesylate may improve fasting blood glucose in diabetic Ph+ chronic myelogenous leukemia patients responsive to treatment. J Clin Onocol 22:4653–4655

Veneri D, Franchini M, Bonora E (2005) Imatinib and regression of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 352:1049–1050

Tsapas A, Vlachaki E, Sarigianni M, Klonizakis F, Paletas K (2008) Restoration of insulin sensitivity following treatment with imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) in non-diabetic patients with chronic myelogenic leukemia (CML). Leuk Res 32:674–675

Breccia M, Muscaritoli M, Alimena G. (2005) Reduction of glycosylated hemoglobin with stable insulin levels in a diabetic patient with chronic myeloid leukemia responsive to imatinib. Haematologica 90(Suppl.):ECR21

Agostino N, Chinchilli VM, Lynch CJ et al (2010) Effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (sunitinib, sorafenib, dasatinib, and imatinib) on blood glucose levels in diabetic and nondiabetic patients in general clinical practice. J Oncol Pharm Pract 17:197–202

Fitter S, Vandyke K, Schultz CG, White D, Hughes TP, Zannettino AC (2010) Plasma adiponectin levels are markedly elevated in imatinib-treated chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients: a mechanism for improved insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic CML patients? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:3763–3767

Mariani S, Tornaghi L, Sassone M et al (2010) Imatinib does not substantially modify the glycemic profile in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leuk Res 34:e5–e7

Hägerkvist R, Jansson L, Welsh N (2008) Imatinib mesylate improves insulin sensitivity and glucose disposal rates in rats fed a high-fat diet. Clin Sci (Lond) 114:65–71

Han MS, Chung KW, Cheon HG et al (2009) Imatinib mesylate reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress and induces remission of diabetes in db/db mice. Diabetes 58:329–336

Gur S, Kadowitz PJ, Hellstrom WJ (2010) A protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, imatinib mesylate (gleevec), improves erectile and vascular function secondary to a reduction of hyperglycemia in diabetic rats. J Sex Med 7:3341–3350

Hägerkvist R, Sandler S, Welsh N (2007) Gleevec-mediated protection against diabetes of the NOD mouse and the streptozotocin-injected mouse: possible role of beta-cell NF-kB activation and anti-apoptotic preconditioning. FASEB J 21:618–628

Hägerkvist R, Makeeva N, Elliman S, Welsh N (2006) Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) protects against STZ-induced diabetes and islet cell in vitro. Cell Biol Int 30:1013–1017

Louvet C, Szot GL, Lang J et al (2008) Tyrosine kinase inhibitors reverse type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:18895–18899

Reber L, Da Silva CA, Frossard N (2006) Stem cell factor and its receptor c-Kit as targets for inflammatory diseases. Eur J Pharmacol 533:327–340

Vogel WF, Abdulhussein R, Ford CE (2006) Sensing extracellular matrix: an update on discoidin domain receptor function. Cell Signal 18:1108–1116

Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG et al (2006) Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 24:16–24

Templeton A, Brändle M, Cerny T, Gillessen S (2008) Remission of diabetes while on sunitinib treatment for renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 19:824–825

Rhodes CJ, White MF (2002) Molecular insights into insulin action and secretion. Eur J Clin Invest 32(suppl 3):3–13

Suwa A, Kurama T, Shimokawa T (2010) SHIP2 and its involvement in various diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets 14:727–737

Tamura M, Gu J, Matsumoto K, Aota S, Parsons R, Yamada KM (1998) Inhibition of cell migration, spreading, and focal adhesions by tumor suppressor PTEN. Science 280:1614–1617

Clément S, Krause U, Desmedt F et al (2001) The lipid phosphatase SHIP2 controls insulin sensitivity. Nature 409:92–97

Wang L, Liu Y, Yan Lu S et al (2010) Deletion of Pten in pancreatic β-cells protects against deficient ß-cell mass and function in mouse models of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 59:3117–3126

Elghazi L, Rachdi L, Weiss AJ, Cras-Méneur C, Bernal-Mizrachi E (2007) Regulation of b-cell mass and function by the Akt/protein kinase B signaling pathway. Diab Obes Metab 9:147–157

Taurin S, Sandbo N, Qin Y, Browning D, Dulin NO (2006) Phosphorylation of β-catenin by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 2281:9971–9976

Liu Z, Habener JF (2008) Glucagon-like peptide-1 activation of TCF7L2-dependent Wnt signaling enhances pancreatic beta cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 283:8723–8735

Liu Z, Habener JF (2009) Stromal cell-derived factor-1 promotes survival of pancreatic β-cells by the stabilisation of β-catenin and activation of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2). Diabetologia 52:1589–1598

Dabernat S, Secrest P, Peuchant E (2009) Lack of β-catenin in early life induces abnormal glucose homoeostasis in mice. Diabetologia 52:1608–1617

Genua M, Pandini G, Cassarino MF, Messina RL, Frasca F (2009) c-Abl and insulin receptor signalling. Vitam Horm 80:77–105

Ravassard P, Hazhouz Y, Pechberty S, Bricout-Neveu E, Armanet M, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R (2011) A genetically engineered human pancreatic β cell line exhibiting glucose-inducible insulin secretion. J Clin Invest 121:3589–3597

Dyachok O, Idevall-Hagren O, Sågetorp J et al (2008) Glucose-induced cyclic AMP oscillations regulate pulsatile insulin secretion. Cell Metab 8:26–37

Tian G, Sågetorp J, Xu Y et al (2012) Role of phosphodiesterases in the shaping of sub-plasma membrane cAMP oscillations and pulsatile insulin secretion. J Cell Sci 125:5084–5095

Prasad NK, Werner ME, Decker SJ (2009) Specific tyrosine phosphorylations mediate signal-dependent stimulation of SHIP2 inositol phosphatase activity, while the SH2 domain confers and inhibitor effect to maintain the basal activity. Biochemistry 14:6285–6287

Wong YH, Lee TY, Liang HK et al (2007) KinasePhos 2.0: a web server for identifying protein kinase-specific phosphorylation sites based on sequences and coupling patterns. Nucl Acids Res 35:W588–W594

Vazquez F, Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Sellers WR (2000) Phosphorylation of the PTEN tail regulates protein stability and function. Mol Cell Biol 20:5010–5018

Brown A, Browes C, Mitchell M, Montano X (2000) C-abl is involved in the association of p53 and trk A. Oncogene 19:3032–3040

Koch A, Scherr M, Breyer B et al (2008) Inhibition of Abl tyrosine kinase enhances nerve growth factor-mediated signaling in Bcr-Abl transformed cells via the alteration of signaling complex and the receptor turnover. Oncogene 27:4678–4689

Cipres A, Abassi YA, Vuori K (2007) Abl functions as a negative regulator of Met-induced cell motility via phosphorylation of the adapter protein CrkII. Cell Signal 19:1667–1670

Frasca F, Vigneri P, Vella V, Vigneri R, Wang JYJ (2001) Tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 enhances thyroid cancer cell motile response to hepatocyte growth factor. Oncogene 20:3845–3856

Lin C-I, Whang EE, Moalem J, Ruan DT (2012) Strategic combination therapy overcomes tyrosine kinase coactivation in adrenocortical carcinoma. Surgery 152:1045–1050

Idevall Hagren O, Tengholm A (2006) Glucose and insulin synergistically activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to trigger oscillations of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in beta-cells. J Biol Chem 281:39121–39127

Wisniewski D, Strife A, Swendeman S et al (1999) A novel SH2-containing phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase (SHIP2) is constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated and associated with src homologous and collagen gene (SHC) in chronic myelogenous leukemia progenitor cells. Blood 15:2707–2720

Grempler R, Leicht S, Kischel I, Eickelmann P, Redemann N (2007) Inhibition of SH2-domain containing inositol phosphatase 2 (SHIP2) in insulin producing INS1E cells improves insulin signal transduction and induces proliferation. FEBS Lett 581:5885–5890

Sasaoka T, Fukui K, Wada T et al (2005) Inhibition of endogenous SHIP2 ameliorates insulin resistance caused by chronic insulin treatment in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetologia 48:336–344

Odriozola L, Singh G, Hoang T, Chan AM (2007) Regulation of PTEN activity by its carboxyl-terminal autoinhibitory domain. J Biol Chem 282:23306–23315

Klinger S, Poussion C, Debril MB et al (2008) Increasing GLP-1-induced β-cell proliferation by silencing negative regulation of signaling cAMP response element modulator-α and DUSP14. Diabetes 57:584–593

Mokhtari D, Welsh N (2009) Potential utility of small tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes. Clin Sci (Lond) 118:241–247

Little PJ, Cohen N, Morahan G (2009) Potential of small molecule protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors as immuno-modulators and inhibitors of the development of type 1 diabetes. Sci World J 9:224–228

Bluestone JA, Herold K, Eisenbarth G (2010) Genetics, pathogenesis and clinical interventions in type 1 diabetes. Nature 464:1293–1300

Acknowledgements

The Nordic Network for Clinical Islet Transplantation, supported by the Swedish national strategic research initiative EXODIAB (Excellence Of Diabetes Research in Sweden), and the JDRF are acknowledged for supply of human islets (JDRF award 31-2008-413 and the ECIT Islet for Basic Research program).

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Swedish Research Council (2010-11564-15-3 and 67–14643), the Swedish Diabetes Association, the family Ernfors Fund, Barndiabetesfonden, Åhlén Stiftelse, Svenska Läkaresällskapet, SSMF, Göran Gustafsson Foundation, Stiftelsen Sigurd och Elsa Goljes Minne and the Novo-Nordisk Foundation.

Duality of interest

R. P. Hägerkvist and N. R. Welsh are holders of patent: Use of tyrosine kinase inhibitor to treat diabetes (patent no.: US7875616). Other authors declare that they have no duality of interest associated with their involvement in this study.

Contribution statement

DM, AA-A, KT, TL, JL, OI-H, RGF and AW performed experiments, analysed data and revised the manuscript. PR, RS and AT analysed data and revised the manuscript. NW designed the study, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mokhtari, D., Al-Amin, A., Turpaev, K. et al. Imatinib mesilate-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signalling and improved survival in insulin-producing cells: role of Src homology 2-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase interaction with c-Abl. Diabetologia 56, 1327–1338 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-2868-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-2868-2