Abstract

Research on functions and signalling pathways of insulin has traditionally focused on peripheral tissues such as muscle, fat and liver, while the brain was commonly believed to be insensitive to the effects of this hormone secreted by pancreatic beta cells. However, since the discovery some 30 years ago that insulin receptors are ubiquitously found in the central nervous system, an ever-growing research effort has conclusively shown that circulating insulin accesses the brain, which itself does not synthesise insulin, and exerts pivotal functions in central nervous networks. As an adiposity signal reflecting the amount of body fat, insulin provides direct negative feedback to hypothalamic nuclei that control whole-body energy and glucose homeostasis. Moreover, insulin affects distinct cognitive processes, e.g. by triggering the formation of psychological memory contents. Accordingly, metabolic and cognitive disorders such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease are associated with resistance of central nervous structures to the effects of insulin, which may derive from genetic polymorphisms as well as from long-term exposure to excess amounts of circulating insulin due to peripheral insulin resistance. Thus, overcoming central nervous insulin resistance, e.g. by pharmacological interventions, appears to be an attractive strategy in the treatment and prevention of these disorders. Enhancement of central nervous insulin signalling by administration of intranasal insulin, insulin analogues and insulin sensitisers in basic research approaches has yielded encouraging results that bode well for the successful translation of these effects into future clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

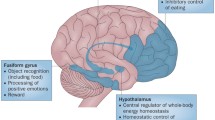

The brain has traditionally been assumed not to be sensitive to the effects of insulin. However, 30 years ago it was shown that insulin receptors are ubiquitously expressed in the central nervous system [1] and solid evidence indicates that insulin accesses the brain from the circulation by crossing the blood–brain barrier (BBB) via an active, receptor-mediated transport system located at endothelial cells of brain microvessels [2]. Research in animals has highlighted the role of insulin in the central nervous regulation of energy homeostasis [2–4] (Fig. 1). Insulin and leptin, one of the endocrine products of white adipose tissue, are regarded to be adiposity signals that convey to the brain the amount of energy stored as fat tissue. Their circulating levels are proportional to body adiposity and decrease during fasting while intracerebroventricular administration of both hormones reduces body fat via negative feedback on food intake [3, 5]. In the hypothalamus, a complex neuropeptidergic signalling network integrates the steady feedback transmitted by insulin and leptin with more acutely acting meal-related signals like ghrelin, cholecystokinin and peptide YY, resulting in the balanced regulation of anabolic and catabolic output, as reviewed by Morton et al. [6]. Moreover, insulin signalling in the hypothalamus is essential for the suppression of hepatic glucose production [7]. Accordingly, mice with a neuron-specific disruption of the insulin receptor are obese and display peripheral insulin resistance and hypertriacylglycerolaemia [8]. Central nervous insulin action also promotes lipogenesis, regulating white adipose tissue metabolism in concert with the direct inhibition of lipolysis by peripheral insulin [9]. In parallel to these effects, insulin enhances memory formation [10], presumably by binding to receptors located in the hippocampus and adjacent limbic brain structures critical for declarative memory, i.e. the acquisition and recall of facts and events.

Schematic model of central nervous insulin effects. Insulin secreted from the pancreas crosses the BBB. By acting on relevant brain structures, insulin improves cognition while reducing food intake and promoting energy expenditure, thereby modulating energy homeostasis. In parallel, central nervous insulin contributes to the inhibition of gluconeogenesis and, together with peripheral insulin, regulates adipocyte metabolism. For details, see the Introduction

Central nervous insulin effects in healthy humans

Anecdotal reports by diabetic patients of reduced awareness of hypoglycaemic episodes after switching from porcine to human insulin triggered early human studies that systematically compared the effects of intravenous porcine and human insulin on central nervous functions and hypoglycaemia counterregulation, but, as reviewed by Jones et al. [11], did not yield fully consistent results. In this context it was demonstrated that insulin enhances the neuroendocrine as well as the subjective response to hypoglycaemia [12]. Under euglycaemic clamp conditions, insulin modulates neuroendocrine and neurocognitive functions in a manner largely independent of its effects on peripheral glucose concentrations, with high as compared with lower rates of insulin infusion acutely increasing activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) stress axis [13], improving declarative memory [14] and reducing hunger [14], which is in line with the concept of insulin being an anorexigenic adiposity signal [6].

The examination of central nervous insulin effects in humans by i.v. infusion of the hormone is severely limited by the emergence of strong systemic side effects mainly on blood glucose concentrations and by the constraints of BBB transport [2]. Intranasal insulin administration bypasses uptake into the bloodstream and allows direct access to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) compartment within 30 min [15] without relevant changes in blood glucose and serum insulin levels [15–20]. Intranasally administered peptides may reach the brain along olfactory but also trigeminal pathways [21]. Given that intraneuronal, axonal transport requires hours to days for substances to reach the brain [22], it is more plausible to assume that intranasal insulin, passing through intercellular clefts in the olfactory epithelium, diffuses into the subarachnoidal space and is rapidly delivered to the CSF [15] and brain tissue [21, 22] via bulk flow transport through perineural channels as reviewed by Hanson and Frey [21]. The functional efficacy of the intranasal route was corroborated by human studies indicating that intranasal insulin exerts rapid effects on EEG measures comparable to those of i.v. bolus injections [16]. Thus, using the intranasal route of insulin administration, biologically effective concentrations of the hormone can be achieved in the human brain in the absence of systemic insulin uptake.

In normal-weight men, intranasal insulin administration for 8 weeks has been shown to reduce body fat, serum leptin levels and waist circumference as compared with placebo treatment [17]. These catabolic effects were not observed in a parallel sample of insulin-treated women, hinting at a sex-related difference in central nervous sensitivity to the adiposity signal insulin. Accordingly, male rats are more susceptible to the anorexigenic effects of intracerebroventricular insulin than female rats, whereas females show a stronger response to intracerebroventricular leptin than males, a pattern proposed to be mediated by the influence of gonadal hormones [23]. In contrast, the catabolic effects of insulin receptor disruption specific to the central nervous system are more pronounced in female than male mice [8], while intranasally administered leptin elicits distinct catabolic/anorexigenic effects in male rats [24]. These controversial findings do not permit solid conclusions regarding a sex-related difference in central nervous processing of adiposity signals, although, in accordance with this assumption, intranasal insulin acutely reduces test buffet consumption in men but not in women [19]. Enhancing central nervous insulin signalling by intranasal administration of the peptide has also repeatedly been demonstrated to improve declarative memory functions, e.g. memory for word lists, in men as well as in women [19, 25, 26]. In line with the strong accumulation of insulin receptors in hippocampal and cortical brain structures [27], this finding corroborates the notion that insulin signalling contributes to the formation of declarative, hippocampus-dependent memory.

Central nervous insulin resistance

In several species including man, acute elevations of plasma insulin levels have been consistently found to induce corresponding increases in CSF insulin concentrations, indicating that the brain content of insulin is normally finely tuned to circulating insulin concentrations [28]. Obese humans, however, whose plasma insulin levels are elevated as a result of peripheral insulin resistance, do not display parallel increases in CSF insulin levels, but rather have a decreased CSF:plasma insulin ratio [29]. Similar observations were made in animals with diet-induced [4] and genetic obesity [30]. Endothelial cells of brain microvessels in obese fa/fa rats exhibit reduced insulin binding [31] that has been shown to result in reduced internalisation of the insulin–insulin receptor complex in rat brain endothelial cells, suggesting that the reduced CSF:plasma insulin ratio reflects impaired transendothelial insulin transport across the BBB in obesity [4]. Comparable results have been obtained for the CSF:plasma ratio of leptin [32] and also of visfatin (also known as pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor and nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase), a peptide produced by adipose tissue as well as other organs with as yet largely unknown physiological effects [33]. These findings support the notion that reduced BBB transport of neuropeptidergic messengers involved in energy homeostasis is an important feature of obesity. Thus, intranasal administration of neuropeptides to target brain functions might be of particular therapeutic relevance because it bypasses the BBB. However, in pilot experiments in obese men, 8 weeks of intranasal insulin treatment had no effect on body weight and body fat mass [18]. Nevertheless, insulin administration improved declarative memory functions and reduced HPA axis secretory activity, effects that resemble those observed in normal-weight participants [20, 25]. This pattern suggests that in obese patients, brain structures involved in energy homeostasis show decreased sensitivity to the effects of insulin. Accordingly, the catabolic impact of intracerebroventricular insulin is curbed in animals with diet-induced obesity, while a partial decrease in insulin receptors selectively pertaining to the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus impairs energy balance and peripheral insulin action in rats [34]. At a molecular level, a defect in the IRS–phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase pathway is likely to be one mechanism of such local neuronal insulin resistance, as described in a review by Schwartz and Porte [35].

A degree of central nervous insulin resistance in overweight humans is also indicated by reduced spontaneous cortical activity as assessed by magneto-encephalography during euglycaemic insulin infusion in overweight vs normal-weight participants [36]. Here, correlational analyses revealed that the effects of insulin on cortical activity were negatively related to the amount of body fat and the degree of peripheral insulin resistance. This outcome contrasts with the fact that, after 8 weeks of intranasal insulin treatment, obese participants displayed preserved susceptibility to the memory-improving effect of insulin [18] in as much as the storage of declarative memory representations also involves neocortical brain areas. However, during i.v. insulin administration in obese participants, insulin resistance at the level of the BBB might be the principal mediator of attenuated central nervous insulin action. It is also tempting to speculate that insulin resistance might affect reward-related brain structures such as the dopaminergic ventral tegmental area, which is targeted by adiposity signals including insulin [37]. In animals, insulinergic input has been demonstrated to downregulate the rewarding value of sucrose solution [38] and disruptions of food–reward-related insulin signalling could promote obesity. Although it would be premature to attempt to pinpoint key sites of insulin resistance in the complex central nervous orchestration of food intake regulation and energy homeostasis, the present data suggest that, besides impaired BBB transport of insulin [4, 29, 30], which can be overridden by intranasal administration of the hormone, insulin resistance of relevant brain regions may contribute to the pathophysiology of obesity and to its persistence despite chronically elevated circulating insulin concentrations. A recent study in humans [39] using positron emission topography found markedly attenuated brain responses to insulin infusion in patients with insulin resistance in the body periphery. Thus, central nervous insulin resistance may not only be relevant in obesity as such, but may particularly affect diabetic patients with reduced peripheral insulin sensitivity, who would probably benefit specifically from new, central nervous approaches to treatment of this disease.

Current research indicates that central nervous insulin resistance might be a common denominator of metabolic disorders and cognitive dysfunctions. Animal data [40] and epidemiological findings in humans [41] suggest that obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes are tightly linked to cognitive impairments. As in obesity [29], CSF insulin levels have also been reported to be reduced in patients with Alzheimer’s disease [42]. The mechanisms behind the relationship between impaired brain insulin signalling, diabetes and/or obesity, and dementia are unclear, but are assumed, as reviewed by Kodl and Seaquist [43], to include a detrimental effect of decreased insulin sensitivity on cholinergic and glutamatergic pathways, which establish neuronal plasticity. Genetic influences are likely in this context, because in memory-impaired humans, intranasal insulin improved memory only in patients without the APOE*E4 allele, a risk factor for the development of Alzheimer’s disease [44]. Accordingly, several genetic polymorphisms associated with reduced central nervous responsiveness to insulin have been identified. Individuals with the Gly972Arg polymorphism of IRS1, as well as those with a polymorphism of the FTO gene show a reduced cerebrocortical response to i.v. insulin [36, 45]. This fits very well with recent data suggesting a connection between the FTO variant and a hyperphagic phenotype characterised by preference for energy-dense foods [46], which, as discussed earlier, might involve reduced insulin sensitivity of food–reward-related pathways [37].

Therapeutic perspectives

A number of approaches to overcome central nervous insulin resistance have been tested in basic research and provided promising results. Thus intranasal insulin administration to increase central nervous availability of the hormone, although apparently ineffective in reducing body weight in the obese state [18], reduces HPA axis activity [18, 20, 25] and may thus counteract the development of visceral obesity, as well as cognitive impairments assumed to be promoted by excessive HPA axis secretion related to chronic stress. Likewise, boosting hypothalamic insulin signalling may help normalise dysregulated hepatic gluconeogenesis [7], a hallmark of type 2 diabetes and peripheral insulin resistance [34], which appears to be highly associated with central nervous insulin resistance [39]. Conceivably, intranasal insulin could also have some impact on weight regulatory mechanisms after successful weight loss has been achieved (e.g. by energy intake restriction and exercise), in this case possibly preventing weight regain. Given that intranasal insulin acutely improved memory functions in adults with mild Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairments [44], it might also slow down the detrimental cognitive changes that obesity and diabetes are suspected to entail [41], although long-term effects of intranasal insulin in humans are yet to be systematically elucidated.

Insulin analogues offer particular promise, in that they may reach the brain in greater quantities than regular human insulin or be designed to specifically target neuronal insulin receptors. Indeed, it has already been shown that after intranasal administration the rapid-acting insulin analogue aspart exerts a stronger effect on improvement of memory performance than regular human insulin [26]. Also, clinical studies indicate that insulin detemir in comparison with other long-acting insulins attenuates weight gain in type 2 diabetic patients, as summarised [47]. Because of its acylation with a fatty acid, detemir is assumed to have facilitated access to the brain due to enhanced BBB transport. Fittingly, i.v. administration of insulin detemir but not human insulin increased cerebrocortical beta activity in obese participants [48].

Insulin sensitisers such as the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist rosiglitazone improve memory function in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease as well as in those with mild cognitive impairments [49], with this effect, like that of intranasal insulin, being restricted to non-carriers of APOE*E4 allele. In rats, rosiglitazone not only reduced the adverse metabolic effects of a high-fat diet, but also its memory-impairing impact [50]. It is tempting to speculate that the mechanisms underlying these observations derive at least in part from an enhancing influence of rosiglitazone on central nervous insulin sensitivity.

Conclusion

There is compelling evidence for the notion that the brain is a primary target of insulin. Central nervous insulin contributes to the regulation of whole-body energy fluxes, eating behaviour and cognitive function. In accordance, experimental studies indicate that central nervous insulin resistance is a critical factor in the pathophysiology of obesity and related metabolic diseases, as well as of cognitive impairments like Alzheimer’s disease. Epidemiological findings suggest a close connection between these disorders, which may stem, at least in part, from the joint occurrence of impaired central nervous insulin signalling. Thus, enhancing insulin signalling in the brain might be a viable therapeutic avenue in the effort to prevent and cure these increasingly common diseases.

Abbreviations

- BBB:

-

Blood–brain barrier

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

References

Havrankova J, Roth J, Brownstein M (1978) Insulin receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system of the rat. Nature 272:827–829

Schwartz MW, Bergman RN, Kahn SE et al (1991) Evidence for entry of plasma insulin into cerebrospinal fluid through an intermediate compartment in dogs. Quantitative aspects and implications for transport. J Clin Invest 88:1272–1281

Woods SC, Lotter EC, McKay LD, Porte D Jr (1979) Chronic intracerebroventricular infusion of insulin reduces food intake and body weight of baboons. Nature 282:503–505

Kaiyala KJ, Prigeon RL, Kahn SE, Woods SC, Schwartz MW (2000) Obesity induced by a high-fat diet is associated with reduced brain insulin transport in dogs. Diabetes 49:1525–1533

Seeley RJ, van DG, Campfield LA et al (1996) Intraventricular leptin reduces food intake and body weight of lean rats but not obese Zucker rats. Horm Metab Res 28:664–668

Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW (2006) Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature 443:289–295

Obici S, Zhang BB, Karkanias G, Rossetti L (2002) Hypothalamic insulin signaling is required for inhibition of glucose production. Nat Med 8:1376–1382

Bruning JC, Gautam D, Burks DJ et al (2000) Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science 289:2122–2125

Koch L, Wunderlich FT, Seibler J et al (2008) Central insulin action regulates peripheral glucose and fat metabolism in mice. J Clin Invest 118:2132–2147

Park CR, Seeley RJ, Craft S, Woods SC (2000) Intracerebroventricular insulin enhances memory in a passive-avoidance task. Physiol Behav 68:509–514

Jones TW, Caprio S, Diamond MP et al (1991) Does insulin species modify counterregulatory hormone response to hypoglycemia? Diabetes Care 14:728–731

Davis SN, Goldstein RE, Jacobs J, Price L, Wolfe R, Cherrington AD (1993) The effects of differing insulin levels on the hormonal and metabolic response to equivalent hypoglycemia in normal humans. Diabetes 42:263–272

Fruehwald-Schultes B, Kern W, Bong W et al (1999) Supraphysiological hyperinsulinemia acutely increases hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal secretory activity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:3041–3046

Kern W, Peters A, Fruehwald-Schultes B, Deininger E, Born J, Fehm HL (2001) Improving influence of insulin on cognitive functions in humans. Neuroendocrinology 74:270–280

Born J, Lange T, Kern W, McGregor GP, Bickel U, Fehm HL (2002) Sniffing neuropeptides: a transnasal approach to the human brain. Nat Neurosci 5:514–516

Hallschmid M, Schultes B, Marshall L et al (2004) Transcortical direct current potential shift reflects immediate signaling of systemic insulin to the human brain. Diabetes 53:2202–2208

Hallschmid M, Benedict C, Schultes B, Fehm HL, Born J, Kern W (2004) Intranasal insulin reduces body fat in men but not in women. Diabetes 53:3024–3029

Hallschmid M, Benedict C, Schultes B, Born J, Kern W (2008) Obese men respond to cognitive but not to catabolic brain insulin signaling. Int J Obes (Lond) 32:275–282

Benedict C, Kern W, Schultes B, Born J, Hallschmid M (2008) Differential sensitivity of men and women to anorexigenic and memory-improving effects of intranasal insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1339–1344

Bohringer A, Schwabe L, Richter S, Schachinger H (2008) Intranasal insulin attenuates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis response to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33:1394–1400

Hanson LR, Frey WH (2008) Intranasal delivery bypasses the blood–brain barrier to target therapeutic agents to the central nervous system and treat neurodegenerative disease. BMC Neurosci 9(Suppl 3):S5

Thorne RG, Emory CR, Ala TA, Frey WH (1995) Quantitative analysis of the olfactory pathway for drug delivery to the brain. Brain Res 692:278–282

Clegg DJ, Brown LM, Woods SC, Benoit SC (2006) Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. Diabetes 55:978–987

Schulz C, Paulus K, Lehnert H (2004) Central nervous and metabolic effects of intranasally applied leptin. Endocrinology 145:2696–2701

Benedict C, Hallschmid M, Hatke A et al (2004) Intranasal insulin improves memory in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29:1326–1334

Benedict C, Hallschmid M, Schmitz K et al (2007) Intranasal insulin improves memory in humans: superiority of insulin aspart. Neuropsychopharmacology 32:239–243

Unger JW, Livingston JN, Moss AM (1991) Insulin receptors in the central nervous system: localization, signalling mechanisms and functional aspects. Prog Neurobiol 36:343–362

Wallum BJ, Taborsky GJ Jr, Porte D Jr et al (1987) Cerebrospinal fluid insulin levels increase during intravenous insulin infusions in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 64:190–194

Kern W, Benedict C, Schultes B et al (2006) Low cerebrospinal fluid insulin levels in obese humans. Diabetologia 49:2790–2792

Stein LJ, Dorsa DM, Baskin DG, Figlewicz DP, Porte D Jr, Woods SC (1987) Reduced effect of experimental peripheral hyperinsulinemia to elevate cerebrospinal fluid insulin concentrations of obese Zucker rats. Endocrinology 121:1611–1615

Schwartz MW, Figlewicz DF, Kahn SE, Baskin DG, Greenwood MR, Porte D Jr (1990) Insulin binding to brain capillaries is reduced in genetically obese, hyperinsulinemic Zucker rats. Peptides 11:467–472

Caro JF, Kolaczynski JW, Nyce MR et al (1996) Decreased cerebrospinal-fluid/serum leptin ratio in obesity: a possible mechanism for leptin resistance. Lancet 348:159–161

Hallschmid M, Randeva H, Tan BK, Kern W, Lehnert H (2009) Relationship between cerebrospinal fluid visfatin (PBEF/Nampt) levels and adiposity in humans. Diabetes 58:637–640

Obici S, Feng Z, Karkanias G, Baskin DG, Rossetti L (2002) Decreasing hypothalamic insulin receptors causes hyperphagia and insulin resistance in rats. Nat Neurosci 5:566–572

Schwartz MW, Porte D Jr (2005) Diabetes, obesity, and the brain. Science 307:375–379

Tschritter O, Preissl H, Hennige AM et al (2006) The cerebrocortical response to hyperinsulinemia is reduced in overweight humans: a magnetoencephalographic study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:12103–12108

Konner AC, Klockener T, Bruning JC (2009) Control of energy homeostasis by insulin and leptin: targeting the arcuate nucleus and beyond. Physiol Behav 97:632–638

Figlewicz DP, Bennett JL, Naleid AM, Davis C, Grimm JW (2006) Intraventricular insulin and leptin decrease sucrose self-administration in rats. Physiol Behav 89:611–616

Anthony K, Reed LJ, Dunn JT et al (2006) Attenuation of insulin-evoked responses in brain networks controlling appetite and reward in insulin resistance: the cerebral basis for impaired control of food intake in metabolic syndrome? Diabetes 55:2986–2992

Stranahan AM, Arumugam TV, Cutler RG, Lee K, Egan JM, Mattson MP (2008) Diabetes impairs hippocampal function through glucocorticoid-mediated effects on new and mature neurons. Nat Neurosci 11:309–317

Whitmer RA, Gustafson DR, Barrett-Connor E, Haan MN, Gunderson EP, Yaffe K (2008) Central obesity and increased risk of dementia more than three decades later. Neurology 71:1057–1064

Craft S, Peskind E, Schwartz MW, Schellenberg GD, Raskind M, Porte D Jr (1998) Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma insulin levels in Alzheimer's disease: relationship to severity of dementia and apolipoprotein E genotype. Neurology 50:164–168

Kodl CT, Seaquist ER (2008) Cognitive dysfunction and diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev 29:494–511

Reger MA, Watson GS, Green PS et al (2008) Intranasal insulin administration dose-dependently modulates verbal memory and plasma amyloid-beta in memory-impaired older adults. J Alzheimers Dis 13:323–331

Tschritter O, Preissl H, Yokoyama Y, Machicao F, Haring HU, Fritsche A (2007) Variation in the FTO gene locus is associated with cerebrocortical insulin resistance in humans. Diabetologia 50:2602–2603

Cecil JE, Tavendale R, Watt P, Hetherington MM, Palmer CNA (2008) An obesity-associated FTO gene variant and increased energy intake in children. N Engl J Med 359:2558–2566

Fritsche A, Haring H (2004) At last, a weight neutral insulin? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28(Suppl 2):S41–S46

Tschritter O, Hennige AM, Preissl H et al (2007) Cerebrocortical beta activity in overweight humans responds to insulin detemir. PLoS One 2:e1196

Watson GS, Cholerton BA, Reger MA et al (2005) Preserved cognition in patients with early Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment during treatment with rosiglitazone: a preliminary study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 13:950–958

Pathan AR, Gaikwad AB, Viswanad B, Ramarao P (2008) Rosiglitazone attenuates the cognitive deficits induced by high fat diet feeding in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 589:176–179

Acknowledgements

Funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO 126, SFB 654).

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hallschmid, M., Schultes, B. Central nervous insulin resistance: a promising target in the treatment of metabolic and cognitive disorders?. Diabetologia 52, 2264–2269 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1501-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1501-x