Abstract

Background

The variant rs11085226 (G) within the gene encoding polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1 (PTBP1) was reported to associate with reduced insulin release determined by an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) as well as an intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT). The aim of the present study was to validate the association of the rs11085226 G-allele of PTBP1 with previously investigated OGTT- and IVGTT-derived diabetes-related metabolic quantitative phenotypes, to conduct exploratory analyses of additional measures of beta-cell function, and to further investigate a potential association with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

PTBP1 rs11085226 was genotyped in 20,911 individuals of Danish Caucasian ethnicity ascertained from 9 study samples. Case control analysis was performed on 5,634 type 2 diabetic patients and 11,319 individuals having a normal fasting glucose level as well as 4,641 glucose tolerant controls, respectively. Quantitative trait analyses were performed in up to 13,605 individuals subjected to an OGTT or blood samples obtained after an overnight fast, as well as in 596 individuals subjected to an IVGTT.

Results

Analyses of fasting and OGTT-derived quantitative traits did not show any significant associations with the PTBP1 rs11085226 variant. Meta-analysis of IVGTT-derived quantitative traits showed a nominally significant association between the variant and reduced beta-cell responsiveness to glucose (β = −0.1 mmol · kg−1 · min−1; 95% CI: −0.200.20 – −0.024; P = 0.01) assuming a dominant model of inheritance, but failed to replicate a previously reported association with area under the curve (AUC) for insulin. Case control analysis did not show an association of the PTBP1 rs11085226 variant with type 2 diabetes.

Conclusions

Despite failure to replicate the previously reported associations of PTBP1 rs11085226 with OGTT- and IVGTT-derived measures of beta-cell function, we did find a nominally significant association with reduced beta-cell responsiveness to glucose during an IVGTT, a trait not previously investigated, leaving the potential influence of this variant in PTBP1 on glucose stimulated insulin release open for further investigation. However, the present study does not support the hypothesis that the variant confers risk of type 2 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) is reaching pandemic proportions with an alarming estimate of 439 million affected individuals world-wide (equal to 7.7% of the world’s population) by the year 2030 [1]. It is well established, that the hyperglycemia observed in T2D arises due to a combination of peripheral insulin resistance and impaired pancreatic beta-cell function and consequently reduced insulin secretion [2,3]. T2D is a heritable [4-6], complex metabolic disorder involving several molecular pathways with currently 90 known genetic susceptibility loci, most of which have been identified in recent years by large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [7]. However, despite recent advances in the understanding of the genetic mechanisms underlying T2D, a substantial part of the heritability (~80-90%) remains unexplained [8].

A candidate-gene study by Heni and colleagues [9] reported a nominal association between reduced glucose stimulated insulin release and the rs11085226 G-allele of the gene encoding polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1 (PTBP1). PTBP1 is a 57 kDa protein consisting of four RNA recognition motifs [10]. It is involved in pre-mRNA and mRNA metabolism as a regulator of alternative splicing, polyadenylation, mRNA stability and initiation of translation [11-13]. It facilitates the biosynthesis and secretion of insulin by binding the pyrimidine rich tract of the 3′-untranslated region of insulin mRNA [14] and other mRNA molecules encoding secretory proteins present in insulin granules of the pancreatic beta-cell [15-17], thus increasing mRNA stability and translation [12,18-20]. Disruption of PTBP1 function, either by siRNA mediated inhibition or mutation of the PTB binding site, results in insulin mRNA destabilization and lower insulin contents [14,15]. Similarly, depletion of PTB levels by microRNA mediated inhibition of PTB-mRNA translation, lowers insulin biosynthesis rates [21]. Also, nuclear retention of PTBP1 has been proposed as a contributing factor in the impairment of rapid glucose-stimulated insulin secretion observed in type 2 diabetic individuals [22]. Variation in the PTBP1 locus may thus affect insulin secretion and could potentially be associated with a type 2 diabetic phenotype.

Assuming a dominant model of inheritance, Heni et al. [9] found that the minor G-allele of PTBP1 rs11085226 was nominally associated with a lower insulinogenic index (IGI) and lower corrected insulin response (CIR) in 1,502 healthy individuals of German ethnicity subjected to an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). In a subset of participants, the variant was also nominally associated with lower insulin levels within the first ten minutes of an intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT). Three additional tag SNPs (rs351974, rs736926 and rs123698) were examined showing no association with OGTT derived measures and only the rs351974 was associated with decreased insulin secretion measured as the AUC for insulin within the first 10 minutes of an IVGTT. The authors also noted that the rs11085226 variant was nominally associated with reduced homeostatic model assessment of beta-cell function (P = .01815) in the publicly available Meta-Analyses of Glucose and Insulin-related traits (MAGIC) consortium dataset [23].

Thus, the aim of the present study was to validate the association of PTBP1 rs11085226 with previously investigated OGTT- and IVGTT-derived diabetes-related metabolic quantitative phenotypes, to conduct exploratory analyses of additional measures of beta-cell function, and to further investigate the association with T2D.

Methods

Subjects and genotyping

Using the KASPTM di-allelic discrimination (LGC Genomics, Herts, UK), the PTBP1 rs11085226 was successfully genotyped in 20,821 individuals, ascertained from 9 study groups (Additional file 1: Table A). Discordance between 1,361 random duplicate samples was 0.0%, and the genotyping success rate was 98.1%. The examined marker obeyed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P = 0.5) with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.084 (95% CI 0.082 – 0.087) which is close to that reported by the International HapMap project (release 24, November 2010, http://www.hapmap.org) [24] for a population of northern and western European origin (MAF = 0.092; 95% CI 0.055 – 0.131).

Case–control analyses were performed with 5,634 type 2 diabetic individuals (study groups 1–6) and non-diabetic controls consisting of either 4,641 glucose-tolerant (as determined by an OGTT) individuals (study groups 1 & 4), or 11,319 individuals having a normal fasting glucose level (excluding impaired glucose tolerance where OGTT data is available; study groups 1–4,6) (Additional file 1: Table B). Analysis of diabetes-related quantitative traits was performed on 13,605 non-diabetic individuals (study groups 1,2,4,6,7), of which 6,183 (study groups 1,4,7) were subjected to an OGTT, and 596 non-diabetic participants (study groups 6, 11) subjected to an IVGTT (Additional file 1: Table B). All participants were Danish Caucasians by self-report and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to participation. Glucose tolerance status was determined by an OGTT and T2D was defined according to the 1999 World Health Organization criteria [25]. All studies were approved by the Ethical Committee for the County of Copenhagen (study groups 1–4,7-9) or the Region of Southern Denmark (study groups 5 and 6), the Danish Data Protection Agency and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. .

Anthropometrics

In all study groups, body weight and height were measured in light indoor clothes and without shoes. BMI was defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2).

OGTT

After a 12-h overnight fast, participants in study groups 1 and 4 underwent a standard 75 g OGTT. Serum insulin and plasma glucose was measured at 0, 30 and 120 minutes. Serum insulin levels (excluding des-31,32 and intact proinsulin) were measured using the AutoDELFIA insulin kit (Perkin-Elmer, Wallac, Turku, Finland). Plasma glucose was analyzed using a glucose oxidase method (Granutest; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) [26].

IVGTT

Youth92

Following a 12-h overnight fast, individuals underwent an IVGTT. After insertion of a cannula into the antecubital vein each subject rested in a quiet room for at least 20 min. Baseline values of serum insulin, serum C-peptide, and plasma glucose were taken in duplicate with 5-min intervals. Glucose was injected intravenously in the contralateral antecubital vein over a period of 60 s (0.3 g/kg body weight of 50% glucose). At 20 min after the glucose injection, a bolus of 3 mg tolbutamide/kg body weight (Rastinon, Hoechst, Germany) was injected over 5 s to elicit a secondary pancreatic beta-cell response. Venous blood was sampled at 2, 4, 8, 19, 22, 30, 40, 50, 70, 90, and 180 min, after glucose injection for measurements of plasma glucose, serum insulin and serum C-peptide. All IVGTTs were done by the same investigator. Plasma concentration of glucose (Diagnostica, Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was analyzed using standardized methods. Serum insulin levels (excluding des-31,32 and intact proinsulin) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), applying the Dako insulin kit with overnight incubation (code No. K6219; Dako Diagnostics Ltd., Ely, United Kingdom) [27]. The concentration of C-peptide was determined by radioimmunoassay [28] using the polyclonal antibody M1230 [29,30].

Family studies

After a 12-hour overnight fast, participants were subjected to an IVGTT in which glucose min (0.3 g/kg body weight of 50% glucose) was injected in the contralateral antecubital vein over a period of 1 minute. At 20 min, a bolus of 3 mg tolbutamide/kg body weight (Orinase, Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) was injected over 5 seconds to elicit a secondary pancreatic beta-cell response. Venous blood samples were drawn in triplicate at 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 30, 35, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 120, 140, 160, and 180 minutes for analysis of plasma concentration of glucose and serum insulin. The plasma glucose concentration was analyzed by a glucose oxidase method (Granutest, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Serum insulin was determined by ELISA excluding des-31,32 and intact proinsulin [27].

Calculations and statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using RGui v3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org/) except the family study sample which was analyzed using the SOLAR software package (http://solar.txbiomedgenetics.org/) taking family relation into account through variance component analysis of multipoint relative-pair identity-by-descent probabilities [31]. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was tested using continuity corrected χ2 test. For all analyses, an uncorrected two-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered significant. Individuals with unknown diabetes status were excluded from the analyses.

Case control analysis for T2D

To examine differences in genotype distributions between affected and unaffected subjects (either glucose tolerant or having a normal fasting glucose level, categories non-mutually exclusive) logistic regression was applied, adjusting for sex, age, BMI, and study group. Analyses were conducted assuming either an additive or dominant inheritance model. Differences in allele frequency were examined using Fisher’s exact test.

Quantitative trait analyses – Fasting/OGTT

Insulinogenic index (IGI) was calculated as (Ins30 − Ins0)/Glu30− Glu0) [32]. Corrected insulin response (CIR) was calculated as (100 · Ins30)/(Glu30 · [Glu30 – 3.89]) [33]. The homeostatic model assessment of beta-cell function (HOMA-B) and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as (20 · Ins0)/(Glu0 – 3.5) and (Ins0 · Glu0)/22.5 respectively [34]. BIGTT-AIR was calculated according to Hansen et al. [35], insulin sensitivity (ISI) was calculated according to Matsuda et al. [36] and the disposition index (DI) as ISI · IGI. Areas under the curve (AUC) were calculated using the trapezoidal method and incremental values represents the expression above basal values. A general linear model was used to test quantitative traits for differences between genotype groups, excluding individuals with known or screen detected diabetes. Analyses were performed for an additive and dominant model with adjustment for sex, age, study group and BMI with and without adjustment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). In a subset of individuals (study group 1) the analysis was adjusted for sex, age, BMI and insulin sensitivity (Matsuda). Analyses of DI were adjusted for age, sex, and BMI only. Logarithmic transformation was applied where appropriate.

Quantitative trait analyses – IVGTT

Insulin sensitivity index and glucose effectiveness were calculated using the Bergman MINIMOD computer program developed specifically for the combined intravenous glucose and tolbutamide tolerance test [37-41]. Acute phase insulin (AIR) and C-peptide (ACR) responses were calculated by means of the trapezoidal rule as the incremental values (areas under the curve when expressed above basal values) from 0 to 8 min. Insulin secretion rate (ISR) was estimated from measured serum C-peptide concentrations applying the ISEC software to perform deconvolution [42]. The beta-cell responsiveness to glucose was established by using the linear relationship between ISR and glucose in all participants as an index of beta cell response to glucose (increase in ISR per unit increase in plasma glucose) [43]. The disposition index (DI) was calculated as the product of insulin sensitivity index and first phase insulin responses (0–8 min) [44,45]. Meta-analyses were performed using effect size estimates and SE derived from a linear regression analysis, assuming either an additive or dominant inheritance model with adjustment for age, sex, BMI and insulin sensitivity (Bergman MINIMOD). Analyses of DI were adjusted for age, sex, and BMI only. Traits were log transformed where appropriate. In the meta-analyses both fixed effect (weight of studies estimated using inverse variance) and random effect (weight of studies estimated using DerSimonian-Laird method) [46] were reported.

Results

Case control analysis for T2D

Association analysis in 5,634 T2D individuals and 4,641 glucose-tolerant control subjects showed no significant difference in genotype distribution or allele frequency between affected and unaffected individuals for neither an additive or dominant model of inheritance (Table 1). Expanding the control group to 11,319 individuals by including all individuals having normal fasting glycaemia, did not reveal any significant association across inheritance models (Additional file 1: Table C). To address the issue of collinearity arising from inclusion of study groups with T2D individuals or controls only, further analyses in a subset of studies with both outcomes were performed, showing no significant association between the rs11085226 variant and T2D (Additional file 1: Tables D and E).

Quantitative trait analyses – Fasting/OGTT

Regression analysis of rs11085226 in up to 13,605 non-diabetic individuals, adjusted for age, sex, BMI and study group, with or without adjustment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and assuming either an additive or dominant model of inheritance, showed no significant association with fasting or OGTT-derived variables of glucose homeostasis and beta-cell function (Table 2). In a subset of 5,031 individuals (study group 1) adjustment for insulin sensitivity (Matsuda) in addition to gender, age, and BMI did not reveal any significant associations for neither an additive nor a dominant model (Additional file 1: Table F).

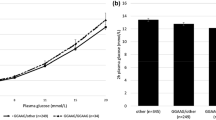

Quantitative trait analyses – IVGTT

In a fixed-effect meta-analysis of the Family- and Youth 92 study (study groups 8 & 9) including IVGTT-derived traits in 596 individuals, the G-allele was significantly associated with lower beta-cell responsiveness to glucose (β-value: −0.11 mmol · kg−1 · min−1; 95% CI: −0.20 – -0.025; P = 0.01) when assuming a dominant model of inheritance and adjusting for age, sex, BMI and insulin sensitivity (Table 3). Despite the absence of any significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 47.3%, P = 0.17), only a P-value of 0.06 was found when using a random-effect analysis (Figure 1). Assuming an additive model of inheritance neither a fixed nor random effect analysis showed any significant associations with any of the IVGTT-derived traits (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, we tried to replicate the previously reported association of PTBP1 rs11085226 with reduced glucose stimulated insulin release in a Danish Caucasian population and to complement with an investigation of measures of beta-cell function and the potential association to T2D. Adjusting for the same covariates as in the original study, we were unable to replicate the reported association with OGTT-derived measures of insulin release. Interestingly, in the MAGIC consortium data released in May 2014, the rs11085226 variant was neither associated with DI (P = 0.71), ISI adjusted CIR (P = 0.86) nor any other OGTT-derived indices of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in up to 5,318 non-diabetic participants from 9 cohorts [47].

In the meta-analysis of IVGTT-derived traits, we did not find an association with AUC insulin, which was previously reported to be significantly reduced in carriers of the rs11085226 minor allele. We did find, however, that the variant is associated with reduced beta-cell responsiveness to glucose which represents the increase in insulin release rate per unit increase in plasma glucose. Interestingly, this measure of acute phase insulin release has previously been found to be reduced by a factor 3 in seven T2D patients of Caucasian ethnicity [43]. In the same study, the reduced beta-cell responsiveness to glucose in T2D patients was rectified during an infusion of a low dose of glucagon-like peptide-1, which points to the possibility that the incretin response following an oral glucose load may compensate for any effect of the rs11085226 G-allele on OGTT-derived measure of beta-cell function. In the present study we did, however, not find an association of the rs11085226 variant with the type 2 diabetic phenotype. According to the database of genetic association studies (available at www.gwascentral.com) the rs11085226 variant has not been tested for association to T2D in individuals of European ancestry, nor is it included in the stage 1 & 2 meta-analysis data of the DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) consortium (data available online at www.diagram-consortium.org) [11]. However, following the completion of our analyses, data from a trans-ethnic meta-analysis including cohorts of individuals with European, Mexican/Mexican American, south Asian and east Asian ancestry became publically available [48], including data on the rs11085226 variant showing no significant association with T2D (OR = 1.01, 95CI: 0.94 - 1.07; P = 0.85; N = 27767).

Given the limited number of studies included in the meta-analysis, caution should be taken when assessing these results, emphasized by the fact that a random effects analysis did not show a significant effect. It should also be noted that assessment of population stratification as a potential bias in the analyses of IVGTT traits was not possible due to the lack of array based genotype data. Yet, beta-cell responsiveness to glucose is a more accurate measure of insulin release than traits derived from levels of circulating insulin. Obtaining a significant result, even if nominal only, despite the relatively small number of subjects in the present study might emphasize the importance of collecting refined traits when assessing complex physiological processes such as beta-cell function. Similarly, given the limited number of subjects in the present study, it is possible that a small effect of the rs11085226 variant on T2D susceptibility remains undetected due to a lack of statistical power. Furthermore, being a heterogeneous disorder poorly defined by a dichotomized end-point, the variant may only affect disease susceptibility in a subset of type 2 diabetic patients.

Clearly the reported association does not hold for stringent correction for 54 independent tests ad modum Bonferroni. However, considering the correlation between the tested traits and the a priori knowledge of the involvement of PTBP1 in insulin secretion, applying the Bonferroni correction might be overly conservative. Furthermore, given that the association of the rs11085226 variant with beta-cell responsiveness to glucose has not previously been reported, this part of the analysis is exploratory and we therefore consider it relevant to report significance at the nominal level only.

In the present study, as well as the previous study by Heni and colleagues [9], the association of the rs11085226 G-allele with reduced glucose-stimulated insulin release was found under the assumption of a dominant model of inheritance. PTBP1 exists in solution as a dimer [49], which could potentially explain the genetic dominance. However, neither rs11085226 nor any of its five known proxies (rs10426084, rs351977, rs10422347, rs10420407, and rs10420953 [in LD with r2 > 0.8 as determined by the Broad Institute's SNP Annotation and Proxy Search website using the CEU panel from the 1000 genomes project pilot 1 and HapMap release 22]), of which only rs10420953 is a coding variant (N108N), results in any non-synonymous amino acid substitutions in the PTBP1 protein. These are however all common variants (MAF > 5%) and one could speculate that the causal variant, which could very well be coding, is rare and uncaptured by chip-based genotyping. Furthermore, a reason why modelling the effect of the variant as additive does not reveal an association might the low number of rare homozygous individuals in the IVGTT cohorts, in which case an additive model does not give an accurate representation of the data.

Conclusion

Although failing to replicate the previously reported association of PTBP1 rs11085226 to OGTT-derived mea sures of beta-cell function, we show a nominal significant association of the variant to reduced beta-cell responsiveness to glucose, a measure of glucose stimulated insulin release not previously investigated in relation to PTBP1. However, any effect the variant may have on beta-cell function does not appear to have a diabetogenic impact. Larger studies of IVGTT-derived measures of dynamic beta-cell function or meta-analysis thereof are needed to thoroughly investigate a potential effect of the rs11085226 variant on glucose-stimulated insulin release.

Abbreviations

- OGTT:

-

Oral glucose tolerance test

- IVGTT:

-

Intravenous glucose tolerance test

- ISR:

-

Insulin secretion rate

- IGI:

-

Insulinogenic index

- IFG:

-

Impaired fasting glucose

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- HOMA-B:

-

Homeostatic model assessment of beta-cell function

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- CIR:

-

Corrected insulin response

- DI:

-

Disposition index

- MAF:

-

Minor allele frequency

- PTBP1:

-

Polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1

- T2D:

-

Type 2 Diabetes

References

Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(1):4–14.

Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, van Haeften TW. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet, 365(9467):1333–46.

DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88(4):787–835.

Poulsen P, Kyvik KO, Vaag A, Beck-Nielsen H. Heritability of type II (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and abnormal glucose tolerance–a population-based twin study. Diabetologia. 1999;42(2):139–45.

Meigs JB, Cupples LA, Wilson PW. Parental transmission of type 2 diabetes: the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes. 2000;49(12):2201–7.

Pierce M, Keen H, Bradley C. Risk of diabetes in offspring of parents with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabet Med. 1995;12(1):6–13.

Grarup N, Sandholt C, Hansen T, Pedersen O. Genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes and obesity: from genome-wide association studies to rare variants and beyond. Diabetologia. 2014;57(8):1528–41.

Drong AW, Lindgren CM, McCarthy MI. The genetic and epigenetic basis of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(6):707–15.

Heni M, Ketterer C, Wagner R, Linder K, Böhm A, Herzberg-Schäfer SA, et al. Polymorphism rs11085226 in the gene encoding polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 negatively affects glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46154.

Oh YL, Hahm B, Kim YK, Lee HK, Lee JW, Song O, et al. Determination of functional domains in polypyrimidine-tract-binding protein. Biochem J. 1998;331(Pt 1):169–75.

Spellman R, Rideau A, Matlin A, Gooding C, Robinson F, McGlincy N, et al. Regulation of alternative splicing by PTB and associated factors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33(Pt 3):457–60.

Sawicka K, Bushell M, Spriggs Keith A, Willis Anne E. Polypyrimidine-tract-binding protein: a multifunctional RNA-binding protein. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(4):641.

Auweter SD, Allain FHT. Structure-function relationships of the polypyrimidine tract binding protein. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(4):516–27.

Tillmar L, Control of Insulin mRNA Stability in Rat Pancreatic Islets. Regulatory role of a 3’-untranslated region pyrimidine-rich sequence. J Biol Chem. 2001;277(2):1099–106.

Knoch K-P, Bergert H, Borgonovo B, Saeger H-D, Altkrüger A, Verkade P, et al. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein promotes insulin secretory granule biogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(3):8–214.

Knoch K-P, Meisterfeld R, Kersting S, Bergert H, Altkrüger A, Wegbrod C, et al. cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of PTB1 promotes the expression of insulin secretory granule proteins in β cells. Cell Metab. 2006;3(2):123–34.

Süss C, Czupalla C, Winter C, Pursche T, Knoch K-P, Schroeder M, et al. Rapid Changes of mRNA-binding Protein Levels following Glucose and 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine Stimulation of Insulinoma INS-1 Cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(3):393–408.

Jang SK, Wimmer E. Cap-independent translation of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA: structural elements of the internal ribosomal entry site and involvement of a cellular 57-kD RNA-binding protein. Genes Dev. 1990;4(9):1560–72.

Cote CA, Gautreau D, Denegre JM, Kress TL, Terry NA, Mowry KL. A xenopus protein related to hnRNP I has a role in cytoplasmic RNA localization. Mol Cell. 1999;4(3):431–7.

Song Y. Evidence for an RNA chaperone function of polypyrimidine tract-binding protein in picornavirus translation. RNA. 2005;11(12):1809–24.

Fred RG, Bang-Berthelsen CH, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Grunnet LG, Welsh N. High glucose suppresses human islet insulin biosynthesis by inducing miR-133a leading to decreased polypyrimidine tract binding protein-expression. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10843.

Ehehalt F, Knoch K, Erdmann K, Krautz C, Jäger M, Steffen A, et al. Impaired insulin turnover in islets from type 2 diabetic patients. Islets. 2010;2(1):30–6.

Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP, Wheeler E, Montasser ME, Luan J, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):991–1005.

Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Hardenbol P, Willis TD, Yu F, Yang H, et al. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426(6968):789–96.

Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15(7):539–53.

Glümer C, Jørgensen T, Borch-Johnsen K. Prevalences of diabetes and impaired glucose regulation in a Danish population: the Inter99 study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2335–40.

Andersen L, Dinesen B, Jorgensen PN, Poulsen F, Roder ME. Enzyme immunoassay for intact human insulin in serum or plasma. Clin Chem. 1993;39(4):578–82.

Heding LG. Specific and direct radioimmunoassay for human proinsulin in serum. Diabetologia. 1977;13(5):467–74.

Faber OK, Markussen J, Naithani VK, Binder C. Production of antisera to synthetic benzyloxycarbonyl-C-peptide of human proinsulin. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1976;357(6):751–7.

Faber OK, Binder C, Markussen J, Heding LG, Naithani VK, Kuzuya H, et al. Characterization of seven C-peptide antisera. Diabetes. 1978;27 Suppl 1:170–7.

Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(5):1198–211.

Phillips DIW, Clark PM, Hales CN, Osmond C. Understanding oral glucose tolerance: comparison of glucose or insulin measurements during the oral glucose tolerance test with specific measurements of insulin resistance and insulin secretion. Diabet Med. 1994;11(3):286–92.

Sluiter WJ, Erkelens DW, Reitsma WD, Doorenbos H. Glucose tolerance and insulin release, a mathematical approach I: assay of the beta-cell response after oral glucose loading. Diabetes. 1976;25(4):241–4.

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–9.

Hansen T, Drivsholm T, Urhammer SA, Palacios RT, Vølund A, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. The BIGTT test: a novel test for simultaneous measurement of pancreatic β-cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):257–62.

Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(9):1462–70.

Pacini G, Bergman RN. MINMOD: a computer program to calculate insulin sensitivity and pancreatic responsivity from the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1986;23(2):113–22.

Steil GM, Volund A, Kahn SE, Bergman RN. Reduced sample number for calculation of insulin sensitivity and glucose effectiveness from the minimal model: suitability for use in population studies. Diabetes. 1993;42(2):250–6.

Steil GM, Murray J, Bergman RN, Buchanan TA. Repeatability of insulin sensitivity and glucose effectiveness from the minimal model: implications for study design. Diabetes. 1994;43(11):1365–71.

Ferrari P, Alleman Y, Shaw S, Riesen W, Weidmann P. Reproducibility of insulin sensitivity measured by the minimal model method. Diabetologia. 1991;34(7):527–30.

Yang YJ, Youn JH, Bergman RN. Modified protocols improve insulin sensitivity estimation using the minimal model. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(6 Pt 1):E595–602.

Hovorka R, Koukkou E, Southerden D, Powrie JK, Young MA. Measuring prehepatic insulin secretion using a population model of C-peptide kinetics: accuracy and required sampling schedule. Diabetologia. 1998;41(5):548–54.

Kjems LL, Holst JJ, Volund A, Madsbad S. The influence of GLP-1 on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: effects on beta-cell sensitivity in type 2 and nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes. 2003;52(2):380–6.

Bergman RN, Phillips LS, Cobelli C. Physiologic evaluation of factors controlling glucose tolerance in man: measurement of insulin sensitivity and beta-cell glucose sensitivity from the response to intravenous glucose. J Clin Invest. 1981;68(6):1456–67.

Bergman RN. Lilly lecture 1989: toward physiological understanding of glucose tolerance: minimal-model approach. Diabetes. 1989;38(12):1512–27.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Prokopenko I, Poon W, Mägi R, Prasad BR, Salehi SA, Almgren P, et al. A central role for GRB10 in regulation of islet function in man. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(4):e1004235.

Replication DIG, Meta-analysis C, Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network Type 2 Diabetes C, South Asian Type 2 Diabetes C, Mexican American Type 2 Diabetes C, Type 2 Diabetes Genetic Exploration by Next-generation sequencing in multi-Ethnic Samples C, Mahajan A, Go MJ, Zhang W, Below JE, et al. Genome-wide trans-ancestry meta-analysis provides insight into the genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):234–44.

Pérez I, McAfee JG, Patton JG. Multiple RRMs contribute to RNA binding specificity and affinity for polypyrimidine tract binding protein†. Biochemistry. 1997;36(39):11881–90.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank A. Forman, T. Lorentzen, B. Andersen, M. Andersen, and G. Klavsen for technical assistance and A. Nielsen, P. Sandbeck, and G. Lademann for managerial assistance.

This work was supported by research grants from The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, an independent research center at the University of Copenhagen partially funded by an unrestricted donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (www.metabol.ku.dk), The Lundbeck Foundation (www.lucamp.org), The Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation, the PhD School of Molecular Metabolism, University of Southern Denmark, and the Copenhagen Graduate School of Health and Medical Sciences. Funders had no influence on study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The Inter99 study was initiated by T. Jørgensen (principal investigator), K. Borch-Johnsen (co-principal investigator), H. Ibsen, and T.F. Thomsen. The steering committee comprises the former two and C. Pisinger. The Inter99 project was financially supported by research grants from the Danish Research Council, The Danish Centre for Health Technology Assessment, Novo Nordisk, Research Foundation of Copenhagen County, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Health, The Danish Heart Foundation, The Danish Pharmaceutical Association, The Augustinus Foundation, The Ib Henriksen Foundation, and the Becket Foundation.

The Health2006 and Health2010 studies were initiated by A. Linneberg (principal investigator) and T. Jørgensen (co-principal investigator).

The ADDITION study was initiated by K. Borch-Johnsen (principal investigator), T. Lauritzen (principal investigator), and A. Sandbæk. The study was supported by the National Health Services in the counties of Copenhagen, Aarhus, Ringkøbing, Ribe and South Jutland, together with the Danish Research Foundation for General Practice, Danish Centre for Evaluation and Health Technology Assessment, the diabetes fund of the National Board of Health, the Danish Medical Research Council, the Aarhus University Research Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The study received unrestricted grants from Novo Nordisk, Novo Nordisk Scandinavia, Astra Denmark, Pfizer Denmark, GlaxoSmithKline Pharma Denmark, Servier Denmark and HemoCue Denmark.

The study of the 1936 Birth cohort was initiated by H. Hollnagel and continued by T. Jørgensen (principal investigator). The Danish Heart Foundation and The Danish Medical Research Council financially supported the 1996/97 investigation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

MEJ is employed by the Steno Diabetes Center A/S, which is a research and teaching hospital collaborating with the Danish National Health Service and owned by Novo Nordisk A/S. Additionally, TH, OP, and MEJ hold shares in Novo Nordisk A/S. All other authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

THH and APG conceived the study and performed the analyses, the interpretation of results and the drafting of the manuscript. TJ, TL, MEJ, TH, IB, CC and OP were involved in the initiation and collection of the study populations. TH, HV and OP conceived the study, and participated in its design and co-ordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Supplementary tables and description of methods.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, T.H., Vestergaard, H., Jørgensen, T. et al. Impact of PTBP1 rs11085226 on glucose-stimulated insulin release in adult Danes. BMC Med Genet 16, 17 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-015-0160-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-015-0160-7