Abstract

Key message

Based on their consistency over environments, two QTL identified in Lillian on chromosomes 5A and 7A could be useful targets for marker assisted breeding of common bunt resistance.

Abstract

Common bunt of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) caused by Tilletia tritici and T. laevis is an economically important disease because of losses in grain yield and reduced grain quality. Resistance can be quantitative, under the control of multiple small effect genes. The Canada Western Red Spring wheat variety Lillian is moderately resistant to common bunt races found on the Canadian prairies. This study was conducted to identify and map quantitative trait loci (QTL) conferring resistance against common bunt in Lillian. A doubled haploid population comprising 280 lines was developed from F1 plants of the cross of Lillian by Vesper. The lines were inoculated at seeding with the two races L16 (T. laevis) and T19 (T. tritici), grown in field near Swift Current, SK, in 2014, 2015 and 2016 and assessed for disease incidence. The lines were genotyped with the 90 K iSelect SNP genotyping assay, and a high-density genetic map was constructed. Quantitative trait locus analysis was performed with MapQTL.6® software. Two relatively stable common bunt resistance QTL, detected in two of the 3 years, were identified on chromosomes 5A and 7A from Lillian. In addition, three less stable QTL, appearing in one out of 3 years, were identified: one was contributed by Lillian on chromosome 3D and two were contributed by Vesper on chromosomes 1D and 2A. Epistatic interaction was identified for the bunt incidence between 3D and 7A resulting in greater bunt resistance. Future bunt resistance breeding will benefit from combining these QTL through gene pyramiding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Common bunt (syn. stinking smut) caused by Tilletia tritici (Bjerk.) Wint. and T. laevis Kühn is a serious disease, reducing yield and quality in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (Gaudet and Menzies 2012; Goates 1996; Hoffmann 1982). The disease is initiated by teliospores on the seed or in the soil germinating and infecting the developing seedling. The fungus progresses systemically in the plant, eventually replacing kernels with bunt balls containing masses of spores (Gaudet et al. 1993). Yield loss due to common bunt is approximately equivalent to the percentage of infected tillers (Menzies et al. 2006). Loss in grain quality occurs in grain contaminated with bunt balls at levels as low as 0.05% by weight. The disease remains a serious problem to wheat production worldwide despite the extensive amount of research conducted (Gaudet and Menzies 2012; Goates 1996). Common bunt is most notably a problem in organic wheat production because traditional seed treatment fungicides are not permitted (Gaudet and Menzies 2012).

In addition to wheat, which is the primary host of common bunt, other cereals such as rye and barley and several grasses can serve as hosts (Gaudet and Menzies 2012). Host adaptation of Tilletia species may exist within wheat and other crops. For example, Mamluk (1998) reported that T. laevis predominates in bread wheat, whereas T. tritici infects both bread and durum nonpreferentially. Apart from host resistance, seed treatment fungicides and cultural practices can reduce common bunt significantly (Gaudet and Menzies 2012; Knox et al. 2013). However, fungicides are expensive, have toxicity issues, present an environmental hazard and have availability and distribution challenges (Goates 1996). The use of resistant varieties offers the best solution for the control of bunt. Genetic resistance to common bunt is relatively easy to select because high infection levels are possible in inoculated field trials (Gaudet and Menzies 2012).

Most Canadian hard red spring wheat varieties grown prior to 1940 were susceptible to common bunt; however, the majority of varieties developed since that time possess intermediate to high levels of resistance (Gaudet et al. 1993; Gaudet and Puchalski 1989a). An understanding of the genetic control in contemporary Canadian wheat varieties carrying common bunt resistance genes is developing (Fofana et al. 2008; Gaudet et al. 1993, 2007; He and Hughes 2003; Knox et al. 2013; Singh et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2009).

Over 15 common bunt major resistance genes Bt1 through Bt15 and Btp have been designated in wheat (Goates 1996, 2012). Among these, Bt10 is effective against all known naturally occurring common bunt races globally and is an important resistance source for new wheat varieties (Chen et al. 2016; Demeke et al. 1996; Gaudet et al. 2007). Several of the designated common bunt resistance genes have known chromosomal location. Bt10 is genetically mapped to the terminal end of chromosome 6DS (Menzies et al. 2006) and Bt9 mapped as a distinct factor on the distal end of chromosome 6DL (Steffan et al. 2017). Wad and Metzger (1970) reported that Bt1 is located on chromosome 2B, and Bt4 and Bt6 are located on chromosome 1B linked with the gene that regulates red glume color.

Quantitatively inherited resistance to common bunt also exists (Fofana et al. 2008). Quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with common bunt resistance were reported on several wheat chromosomes: two QTL were identified on chromosome 1B and a third on chromosome 7A in AC Domain (Fofana et al. 2008), 1BS in Blizzard (Wang et al. 2009), 7B in McKenzie (Knox et al. 2013), 2B and 6A in Kenyon (McCartney et al. 2013), 1B, 4B, 4D, 5B and 7D in Carberry (Singh et al. 2016) and 1A, 2B and 7D in Idaho 444 (Chen et al. 2016). Dumalasová et al. (2012) reported a strong bunt QTL on chromosome 1B with other smaller effect QTL expressed on 5B, 7A and 7D in a European winter wheat variety Trintella.

Mapping genes for resistance to common bunt in wheat is valuable for gene pyramiding and deployment in future varieties. Molecular markers enable pyramiding resistance genes of interest into a single germplasm minimizing the need for greenhouse or field evaluation, thereby greatly simplifying the screening and selection process (Gaudet and Menzies 2012). Gene pyramiding could increase the longevity and effectiveness of resistance. The objective of this study was to identify and map quantitative trait loci (QTL) conferring resistance against common bunt in the wheat cultivar Lillian.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

A population of 280 DH lines developed from F1 plants of the cross Vesper/Lillian at the Swift Current Research and Development Centre with the maize by wheat system (Humphreys and Knox 2015) was used for this study. At the time of its commercial release, Lillian was moderately resistant to common bunt (DePauw et al. 2005), while Vesper was moderately susceptible (Thomas et al. 2013).

Similar to the procedure described by Knox et al. (2013), the DH lines, parents and bunt checks were evaluated for common bunt reaction in an experiment planted in a disease nursery established near Swift Current, SK (50°15′38″N 107°44′28″W), in each of the years 2014, 2015 and 2016. The experiments were planted in moist soil of a field that was summer fallow the previous growing season early in the spring to obtain cool soil conditions that favor common bunt development. Planting was performed on April 25, 2014 with a 5-cm soil depth mean temperature of 6 °C, on April 17, 2015 with a 5-cm soil depth temperature of 6 °C and on April 20, 2016 with a 5-cm soil depth temperature of 9 °C. Prior to planting, seeds of the lines, parents and checks were inoculated with spores of two common bunt races, L16 (T. laevis) and T19 (T. tritici) (Goates 2012; Singh et al. 2016). The L16 and T19 races together represent the entire bunt virulence spectrum in Canada (Gaudet and Puchalski 1989b; Singh et al. 2016).

In each of the 3 years, the DH lines, parents and bunt checks were planted in a completely randomized design of 3-m-long rows seeded at a rate of 200 seeds per row spaced 0.46 m apart (135 seeds m−2). The bunt checks Biggar (DePauw et al. 1991), Katepwa (Campbell and Czarnecki 1987), Neepawa (Campbell 1970), AC Barrie (McCaig et al. 1996), AC Cadillac (DePauw et al. 1998) and AC Elsa (Clarke et al. 1997) were repeated six times in each nursery with the exception of Neepawa that was not included in the 2016 nursery. The parents appeared once in the 2014 and 2015 nurseries; in 2016, each parent was repeated six times. Biggar was used as a bunt-susceptible check (Singh et al. 2016). The other checks have varying phenotypic expression, ranging from moderately susceptible to resistant. Disease incidence was recorded as a percentage of bunt-infected spikes over total number of spikes (percent bunt incidence = number of infected spikes/total number of spikes of a genotype * 100) in the row based on a visual assessment when plants reached the hard dough stage. Disease rating was repeated within each season to optimize assessment of both early and late developing lines. Where there were multiple checks or parental lines in a test, the mean of that line was used in data analysis. PROC ANOVA with a Duncan multiple range test was performed to compare bunt incidence between lines and checks using SAS (SAS institute, Cary, NC) with all data, using year as replicate.

Genotyping and QTL mapping

The DNA of parents and Vesper/Lillian population lines was extracted from young leaves using Daisy 96 Plant Kits (QIAGEN Science, Maryland, USA) and genotyped with the 90 K iSelect SNP genotyping assay (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). Genotypic data were curated to remove monomorphic and highly distorted markers according to an expected 1:1 ratio for the population using the Chi-square test. A linkage map consisting of 7841 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers spanning 3679.5 cM was built for the population using the two-step mapping strategy previously described (Fowler et al. 2016; Perez-Lara et al. 2016). The A genome had 3144 markers spanning 1643.1 cM length, the B genome had 3596 markers covering 1398.8 cM and the D genome had 1099 markers over 637.6 cM. All chromosomes were represented in the map. Simple interval mapping (SIM) followed by multiple QTL mapping (MQM) analysis was performed using a set of 1975 nonoverlapping SNP markers using MapQTL.6 ® (Van Ooijen 2009). Where markers overlapped at specific map positions, the marker with results across the most lines of the population was retained and the redundant markers were removed.

Epistasis interactions between the QTL for bunt resistance were analyzed using QTL-Network v.2 as previously described, and critical F values were determined with 1000 permutations (Singh et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2007). The “two-dimensional (2D) genome scan” option was used to map epistatic QTL with or without single-locus effects. To estimate effects of the additive × additive (A × A) interaction in a doubled haploid population, the “map epistasis” option was used. A t test analysis comparing 3 years’ least square means of bunt incidence data for 32 groups of lines carrying varying numbers of common bunt resistance QTL was run using the LSMEANS statement with the PDIFF option of the PROC GLM in SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Mean comparisons were made using the hypothesis [Pr > |t| for H0: LSMean (column group i) = LSMean (row group j)].

Results

Bunt incidence

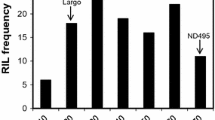

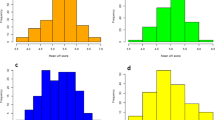

When comparing results of the phenotypic data of the parents and checks, the moderately resistant parent Lillian (\( \bar{x} \) = 6.0%) and the resistant check AC Cadillac (\( \bar{x} \) = 6.1%) had the lowest disease incidence, while the susceptible check Biggar displayed the highest disease incidence (\( \bar{x} \) = 51.4%) over all 3 years (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Table 1). Check varieties with intermediate resistance Katepwa (\( \bar{x} \) = 14.0%), Neepawa (\( \bar{x} \) = 14.3%—2 years data) and AC Barrie (\( \bar{x} \) = 15.7%) showed lower disease incidence than moderately susceptible Vesper (\( \bar{x} \) = 27.8%) and AC Elsa (\( \bar{x} \) = 23.8%). The mean disease incidence of Lillian was not statistically different from other checks except Vesper and Biggar. The distribution of the population lines for disease response was continuous with a majority of the lines showing resistance over the 3 years (Fig. 1b). No line demonstrated complete resistance. Four of the 280 DH lines (AJ091, AC037, AN089 and AH055) consistently had lower disease incidence than Lillian in each of the 3 years; this difference was statistically nonsignificant. The susceptible check Biggar was more susceptible than the most susceptible population line in 2016. Biggar also showed a similar reaction to the most susceptible line in 2015 and was relatively less susceptible in 2014. Biggar had significantly higher disease incidence than the parents, checks and all population lines except AC066, AN021, AC085 and AC005. These four lines were also not significantly different from Vesper. Bunt incidence of the DH lines ranged from 0 to 45% in 2014, 1 to 50% in 2015 and 3 to 60% in 2016 (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table 1). The mean incidence of the population was 14.3% in 2014, 14.2% in 2015 and 18.0% in 2016.

Swift Current, SK field nursery common bunt percent incidence in 2014, 2015 and 2016 of: a parents and check varieties and b plot of frequency distribution of the doubled haploid lines (n = 280) of the “Vesper”/“Lillian” cross along with the incidence of parental lines Lillian and Vesper designated by arrows for each year of testing

The rainfall during the plant growth period (April–July) at the experimental site was 222 mm for 2014, 141 mm for 2015 and 372 mm for 2016 with the monthly distributions indicated in Supplementary Fig. 1. The disease score of the lines was generally higher for the wetter season than drier years.

QTL mapping

The QTL mapping revealed five loci associated with common bunt resistance on chromosomes 1D, 2A, 3D, 5A and 7A (Table 1, Fig. 2). The location of the SNP markers that detected the common bunt resistance QTL in the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) RefSeq v1.0 wheat genome assembly is given in Supplementary Table 2. The QTL located on chromosomes 3D (QCbt.spa-3D), 5A (QCbt.spa-5A) and 7A (QCbt.spa-7A) were contributed by the moderately resistant Lillian. The remaining two QTL located on chromosomes 1D (QCbt.spa-1D) and 2A (QCbt.spa-2A) were contributed by the moderately susceptible Vesper. Both QCbt.spa-5A and QCbt.spa-7A QTL were statistically significant in two environments, QCbt.spa-5A being revealed in 2014 and 2015 and QCbt.spa-7A in 2015 and 2016. In 2016, the LOD score of QCbt.spa-5A was elevated but not significant, being 2.2 as compared with the genome-wide threshold of 3.4. Quantitative trait loci that appeared in one out of three test environments were on 1D in 2014, 3D in 2015 and 2A in 2016.

Linkage maps displaying five QTL associated with common bunt resistance contributed by Lillian on chromosomes 3D, 5A and 7A, and Vesper on 1D and 2A. (Based on population size, markers less than 0.4 cM apart are not reliable.) LOD values were generated using Multiple QTL Mapping (MQM) analysis. The column on the left is the map distance in cM corresponding to the 90 K wheat iSelect markers (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) in the center on the Vesper/Lillian population genetic map and LOD score on the right

Despite differences in stability over the three environments, the phenotypic variation explained by each of the five QTL was similar (Table 1). The highest explained incidence variation was 9.1% in 2015 for QTL QCbt.spa-7A associated with marker RAC875_rep_c119304_226 and 9.9% in 2016 for Excalibur_c30730_1503. The lowest was 4.8% of the phenotypic variation explained for QTL QCbt.spa-1D associated with BS00066855_51.

Three of the main effect QTL detected by MapQTL on chromosomes 3D, 5A and 7A were similarly detected by QTL-Network, whereas the two other QTL on 1D and 2A identified by MapQTL were not revealed. Significant additive × additive epistatic interactions for percent bunt incidence occurred between QCbt.spa-3D × QCbt.spa-7A in 2015 and the mean of 3 years (Table 2). Figure 3 displays the additive × additive epistasis interaction between 3D and 7A and the effect on bunt incidence in 2015. Without the 3D and 7A resistance allele, the bunt incidence was 19.2%. The epistatic interaction between the 3D Lillian allele at SNP marker RAC875_c3956_659 and the 7A Lillian allele at SNP marker Excalibur_c30730_1503 resulted in 10.8% bunt incidence as compared with individual effects of 12.5% bunt incidence for the Lillian 7A allele alone and 14.0% bunt incidence for the Lillian 3D allele alone. The interactions between additive × additive (epistatic) × environments were not significant in any of the 3 years.

With five common bunt QTL, 32 unique genotypic groups exist. Table 3 is arranged by decreasing order of the 3-year mean of common bunt incidence for the 32 genotypic groups. The allelic configuration of each of the five QTL is indicated by “+” for the allele associated with reduced disease and “−” for the allele associated with more disease based on QTL analysis. The number of resistance loci per group, the number of lines per genotypic resistance group (ranging from 3 to 13) and the mean of the bunt incidence for the lines within the group in each year and across years are also indicated. Significant differences in disease incidence were observed between some genotypic groups for disease incidence using means across the 3 test years (Supplementary Table 3). Five of the six groups of lines with four or five resistance loci had significantly lower common bunt incidence when compared with five of the six groups of lines that had one or no resistance locus. The sixth groups of each Group 6 (+/+/+/−/+) and Group 27 (−/−/−/−/+) ranked beside each other medially. In some of the groups, there are lines with very different phenotypes. For example, in Group 1 with five resistance loci, line AD065 had incidence ratings of 3% in 2014, 3% in 2015 and 10% in 2016, while line AZ041 had incidence ratings of 10%, 20% and 35% for the 3 years. Group 17 (−/−/+/+/−) is split with three lines having fairly low ratings and three lines fairly high ratings. Thirteen lines are not included in Table 3 due to marker–trait recombination; for example, line AN086 carried the Vesper allele at marker CAP8_rep_c4852_130 and the Lillian allele at TA003720-0955 associated with the 5A QTL. Of the four lines that consistently had lower bunt incidence ratings than Lillian over the 3 test years, AJ091, AC037 and AH055 were categorized into Group 2 (−/+/+/+/+) while line AN089 into Group 3 (+/−/+/+/+). Among four lines that were nonsignificantly different from Biggar, line AC066 was categorized into Group 29 (−/−/+/−/−), AC005 and AN021 into Group 31 (+/−/−/−/−) and AC085 into Group 32 (−/−/−/−/−).

Discussion

The highest disease scores of the lines and parents observed in 2016 relative to 2014 and 2015 could be attributed to the high precipitation received in 2016 favoring disease development compared to the other 2 years. The skewed continuous distribution toward resistance of the Vesper/Lillian lines (Fig. 1b) is indicative of multiple resistance genes with incomplete resistance and cumulative effects. Four of the 280 DH lines consistently expressed better resistance than the resistant parent Lillian in each of the 3 years. These lines carried all the Lillian QTL plus one of the QTL from Vesper. The identification of five minor-effect QTL in our study is consistent with the skewed phenotypic distribution. Furthermore, the moderate susceptibility of Vesper and the progeny lines which had consistently lower ratings than Lillian suggests both parents possess unique, but incomplete resistance genes, consistent with the QTL discovered. The observed QTL × environment interaction is consistent with the nature of quantitative expression (Jansen et al. 1995; Young 1996).

The QCbt.spa-5A locus is likely located on the long arm of chromosome 5A as the closely associated markers CAP8_rep_c4852_130 and TA003720-0955 map on the long arm of the chromosome in the wheat consensus map (Wang et al. 2014). We are not aware of other QTL reported for common bunt resistance on chromosome 5A; consequently, QCbt.spa-5A contributed by Lillian is likely novel. The explained variation in the bunt incidence by QCbt.spa-5A of approximately 7% was not high, but the significant expression of the locus in two out of three environments (2014 and 2015) and a reduction in bunt incidence, although not significant, in 2016 indicated the QTL is reasonably stable.

The second relatively consistent QTL QCbt.spa-7A displays a slightly larger effect on the phenotype than QCbt.spa-5A. Unlike QCbt.spa-5A, QTL with a similar effect as QCbt.spa-7A were previously reported on chromosome 7A (Dumalasová et al. 2012; Fofana et al. 2008). Fofana et al. (2008) identified a 7A bunt QTL in a Canadian wheat variety AC Domain, whereas Dumalasová et al. (2012) identified the QTL in a European winter variety Trintella. The LOD values and explained phenotypic variation of the 7A locus in Lillian, AC Domain and Trintella were also similarly modest. Dumalasová and Bartos (2012) suggested that even though the origin of varieties AC Domain and Trintella is remote, the bunt resistance could be the same based on European sources of common bunt resistance used in the USA and Canada. The two Canadian lines AC Domain and Lillian have genetic similarity with the coefficient of parentage approaching 12% [Crop Information Engine and Research Assistant (CIERA)]. Interestingly, microsatellite markers Xgwm63 and Xwmc633 that detected the QTL in AC Domain (Fofana et al. 2008) were monomorphic in the Vesper/Lillian population. Further work would be needed to determine whether the 7A QTL from the three sources are the same or not.

The QTL identified from Lillian and Vesper contributed approximately 35.4% of the total phenotypic variation in bunt incidence, indicating other unaccounted variation. A couple of reasons exist why the genotypic resistance group of nine lines Group 32 (−/−/−/−/−) which did not carry resistance alleles at any of the five QTL had a much lower bunt incidence (24.1%) than the average of Biggar (51.4%). One possibility is below threshold QTL were functioning but not statistically significant and secondly partial bunt resistance factors may be in common between Lillian and Vesper. The minor resistance loci identified in single years (1D in 2014, 2A in 2016 and 3D in 2015) indicate that genotype by environment interactions occurred. Interestingly, these minor QTL displayed similar LOD ratios and explained as high a level of phenotypic variation as the more consistent loci on chromosomes 5A and 7A. Steffan et al. (2017) summarizes chromosome locations of common bunt resistance genes and QTL. As with the 5A chromosome mentioned earlier, 3D, 1D and 2A were not listed as chromosomes known to be associated with common bunt resistance. Investigation of bunt resistance in contemporary varieties like Lillian is valuable for the opportunity to pyramid such genes again in newer varieties. Although multigenic, the level of resistance in Lillian is comparable to AC Cadillac which is known to have a major gene on chromosome 6D, likely Bt10 derived from BW553 (DePauw et al. 1998; Singh et al. 2016). The improvement in bunt resistance of Lillian over previous varieties such as Neepawa indicates the success over the last few decades of persistence in resistance breeding in stacking minor-effect genes. Neepawa, related to Lillian with a 49.3% coefficient of parentage (CIERA), has been used as one of the sources of bunt resistance for many years in Canada (McCartney et al. 2013) and may be the basis of a portion of the resistance in varieties such as Lillian or even Vesper. Unfortunately, Neepawa’s resistance genes have not yet been characterized.

Generally, line groups having four or five resistance loci had significantly lower bunt incidence than those with no or one resistance locus. There were exceptions which could be attributed to small sample size or marker–trait recombination. The small sample size is exemplified by line Group 6 that had only three population lines and ranked much lower than expected for a group having four resistance alleles. Further testing would be required to determine whether the ranking of Group 6 is due to random variation associated with small sample size. Marker–trait recombination was evident in some lines of the population. Markers could be in a loose linkage with the resistance alleles, allowing marker–trait recombination that could lead to misclassification of resistant and susceptible alleles. For example, lines with the concurrent presence of the resistant allele at all five QTL did not display the lowest disease incidence. This can be explained by considering the phenotype of individual lines whereby one line of the group had a much higher bunt phenotype over all years affecting the group’s mean and ranking. The aberrant line could possess a susceptible allele or alleles as a consequence of double crossovers.

An additive effect is the reduced incidence of bunt because of the contribution of alleles at more than one locus (Singh et al. 2016). The interaction between 3D and 7A is positive, as presented in Fig. 3 and Table 2. The percent bunt incidence of the respective groups of DH lines carrying individual resistance alleles appeared higher than a simple additive effect when the 3D resistance allele was in harmony with the 7A resistance allele indicating a positive epistatic response. Genotype by environment interaction is indicated as the epistatic response was not significant in all years. Identification of significant positive (enhanced resistance) or negative (susceptible) QTL interactions is important in breeding for disease resistance to allow the deployment of allele combinations with positive synergistic effects (Singh et al. 2016, 2013).

The detection of 3D, 5A and 7A QTL with both MapQTL and QTL-Network indicates consistency in analysis between two different softwares which generates more confidence in the analysis. The manifestation of additive × additive epistatic interactions between the unstable 3D and relatively stable 7A loci in the present study indicates the importance of minor QTL in boosting resistance when combined with other QTL. The modest LOD score and low-explained phenotypic variance of 5% by the QCbt.spa-3D alone would suggest that the locus is less valuable for resistance breeding compared with the 5A and 7A loci, but this would miss the small, but positive synergistic contribution obtained through epistasis. Even though the population studied was quite large, at 280 lines, revealing five minor bunt resistance genes segregating, a larger population would assist in further elucidating the effect of additional minor loci. Although not significantly different, we identified lines that had lower disease ratings than Lillian across 3 experimental years. The genotyping showed transgressive segregation, with all four lines possessing the haplotype of the parents contributing resistant alleles at four loci compared to three resistant loci in Lillian. Sampling more environments would be useful to understand the consistency of expression of the loci and perhaps would reveal additional loci.

In conclusion, the present research revealed novel but minor-effect common bunt resistance loci that segregated from both parents of a cross of Canadian adapted varieties Lillian and Vesper. Our results suggested certain combinations of the genes are more effective. Two of the QTL located on chromosomes 3D and 7A showed at least an additive × additive epistatic effect. The results indicated resistance as good or even better than Lillian is possible through pyramiding certain combinations of the genes. Environment appeared to play a role in the expression of the gene combinations, but more environmental sampling is required to understand the best long-term gene combinations. Based on their consistency over environments, the two QTL that mapped to chromosomes 5A and 7A would be the best initial targets for marker-assisted selection as a base on which to build other loci through selection in a bunt-inoculated nursery. Lines identified through this study having both Lillian and Vesper resistance alleles could be used as future parents in further improvement in bunt resistance and variety development.

References

Campbell AW (1970) Neepawa hard red spring wheat. Can J Plant Sci 50:752–753

Campbell AB, Czarnecki E (1987) Katepwa hard red spring wheat. Can J Plant Sci 67:229–230

Chen J, Guttieri MJ, Zhang J, Hole D, Souza E, Goates B (2016) A novel QTL associated with dwarf bunt resistance in Idaho 444 winter wheat. Theor Appl Genet 129:2313–2322

Clarke JM, DePauw RM, McCaig TN, Fernandez MR, Knox RE, McLeod JG (1997) AC Elsa hard red spring wheat. Can J Plant Sci 77:661–663

Demeke T, Laroche A, Gaudet DA (1996) A DNA marker for the Bt-10 common bunt resistance gene in wheat. Genome 39:51–55

DePauw RM, Preston KR, Townley-Smith TF, Hurd EA, McCrystal GE, Lendrum CWD (1991) Biggar red spring wheat. Can J Plant Sci 71:519–522

DePauw RM, Thomas JB, Knox RE, Clarke JM, Fernandez MR, McCaig TN, McLeod JG (1998) AC Cadillac hard red spring wheat. Can J Plant Sci 78:459–462

DePauw RM, Townley-Smith TF, Humphreys G, Knox RE, Clarke FR, Clarke JM (2005) Lillian hard red spring wheat. Can J Plant Sci 85:397–401

Dumalasová V, Bartos P (2012) Wheat screening for resistance to common bunt and dwarf bunt. Tagung der Vereinigung der Pflanzenzüchter und Saatgutkaufleute Österreichs 2012, pp 51–54. ISBN 978-3-902559-88-3

Dumalasová V, Simmonds J, Bartoš P, Snape J (2012) Location of genes for common bunt resistance in the European winter wheat cv Trintella. Euphytica 186:257–264

Fofana B, Humphreys DG, Cloutier S, McCartney CA, Somers DJ (2008) Mapping quantitative trait loci controlling common bunt resistance in a doubled haploid population derived from the spring wheat cross RL4452 × AC Domain. Mol Breed 21:317–325

Fowler DB, N’Diaye A, Laudencia-Chingcuanco D, Pozniak CJ (2016) Quantitative trait loci associated with phenological development, low-temperature tolerance, grain quality, and agronomic characters in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS ONE 11(3):e0152185

Gaudet D, Menzies J (2012) Common bunt of wheat: an old foe remains a current threat. In: Sharma I (ed) Disease resistance in wheat. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, pp 220–235

Gaudet DA, Puchalski BJ (1989a) Status of bunt resistance in western Canadian spring wheat and triticale. Can J Plant Sci 69:797–804

Gaudet DA, Puchalski BL (1989b) Races of common bunt (Tilletia caries and T. foetida) of wheat in western Canada. Can J Plant Pathol 11:415–418

Gaudet D, Puchalski BJ, Kozub GC, Schaalje GB (1993) Susceptibility and resistance in Canadian spring wheat cultivars to common bunt (Tilletia tritici and T laevis). Can J Plant Sci 73:1217–1224

Gaudet DA, Lu ZX, Leggett F, Puchalski B, Laroche A (2007) Compatible and incompatible interactions in wheat involving the Bt-10 gene for resistance to Tilletia tritici, the common bunt pathogen. Phytopathology 97:1397–1405

Goates BJ (1996) Common bunt and dwarf bunt. In: Wilcoxson RD, Saari EE (eds) Bunt and smut disease of wheat: concepts and methods of disease management. CIMMYT, Mexico, pp 12–25

Goates BJ (2012) Identification of new pathogenic races of common bunt and dwarf bunt fungi, and evaluation of known races using an expanded set of differential wheat lines. Plant Dis 96:361–369

He C, Hughes GR (2003) Inheritance of resistance to common bunt in spelt and common wheat. Can J Plant Sci 83:47–56

Hoffmann JA (1982) Bunt of wheat. Plant Dis 66:979–986

Humphreys DG, Knox RE (2015) Doubled haploid breeding in cereals. In: Al-Khayri JM et al (eds) Advances in plant breeding strategies: breeding: biotechnology and molecular tools. Springer, Berlin, pp 241–290

Jansen RC, Van Ooijen JW, Stam P, Lister C, Dean C (1995) Genotype-by-environment interaction in genetic mapping of multiple quantitative trait loci. Theor Appl Genet 91:33–37

Knox RE, Campbell HL, Depauw RM, Gaudet D, Puchalski B, Clarke FC (2013) DNA markers for resistance to common bunt in ‘McKenzie’ wheat. Can J Plant Pathol 35:328–337

Mamluk OF (1998) Bunts and smuts of wheat in North Africa and the Near East. Euphytica 100:45–50

McCaig TN, DePauw RM, Clarke FC, McLeod JG, Fernandez MR, Knox RE (1996) AC Barrie hard red spring wheat. Can J Plant Sci 76:337–339

McCartney C, Gaudet D, Knox K, Menzies J (2013) QTL analysis of common bunt resistance in the ‘Kenyon’/86ISMN 2137 mapping population. XXI plant and animal genome conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 Jan 2013

Menzies JG, Knox RE, Popovic Z, Procunier JD (2006) Common bunt resistance gene Bt10 located on wheat chromosome 6D. Can J Plant Sci 86:1409–1412

Perez-Lara E, Semagn K, Chen H, Iqbal M, N’Diaye A, Kamran A, Navabi A, Pozniak C, Spaner D (2016) QTLs associated with agronomic traits in the Cutler × AC Barrie spring wheat mapping population using single nucleotide polymorphic markers. PLoS ONE 11(8):e0160623. https://doi.org/10.1371/journalpone0160623

Singh A, Pandey MP, Singh AK, Knox RE, Ammar K, Clarke JM, Clarke FR, Singh RP, Pozniak CJ, Depauw RM, McCallum BD, Cuthbert RD, Randhawa HS, Fetch TG Jr (2013) Identification and mapping of leaf, stem and stripe rust resistance quantitative trait loci and their interactions in durum wheat. Mol Breed New Strateg Plant Improv 31:405–418

Singh A, Knox RE, DePauw RM, Singh AK, Cuthbert RD, Campbell HL, Shorter S, Bhavani S (2014) Stripe rust and leaf rust resistance QTL mapping, epistatic interactions, and co-localization with stem rust resistance loci in spring wheat evaluated over three continents. Theor Appl Genet 127:2465–2477

Singh A, Knox RE, DePauw RM, Singh AK, Cuthbert RD, Kumar S, Campbell HL (2016) Genetic mapping of common bunt resistance and plant height QTL in wheat. Theor Appl Genet 129:243–256

Steffan PM, Torp AM, Borgen A, Backes G, Rasmussen SK (2017) Mapping of common bunt resistance gene Bt9 in wheat. Theor Appl Genet 130:1031–1040

Thomas J, Fox S, McCallum B, Fetch T, Gilbert J, Menzies J, Wise I, Smith M, Despins T, Niziol D, Humphreys G, Brown D (2013) Vesper hard red spring wheat. Can J Plant Sci 93:315–321

Van Ooijen JW (2009) MapQTL® 6: software for the mapping of quantitative trait loci in experimental populations of diploid species Kyazma BV. Wageningen, The Netherlands, p 59

Wad JL, Metzger RJ (1970) Inheritance of a new factor (Bt8) for resistance to common bunt in Wheat. Crop Sci 10:703–704

Wang S, Knox RE, Depauw RM, Clarke FR, Clarke JM, Thomas JB (2009) Markers to a common bunt resistance gene derived from ‘Blizzard’ wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and mapped to chromosome arm 1BS. Theor Appl Genet 119:541–553

Wang S, Wong D, Forrest K, Allen A, Chao S, Huang BE, Maccaferri M, Salvi S, Milner SG, Cattivelli L, Mastrangelo AM, Whan A, Stephen S, Barker G, Wieseke R, Plieske J, International Wheat Genome Sequencing C, Lillemo M, Mather D, Appels R, Dolferus R, Brown-Guedira G, Korol A, Akhunova AR, Feuillet C, Salse J, Morgante M, Pozniak C, Luo MC, Dvorak J, Morell M, Dubcovsky J, Ganal M, Tuberosa R, Lawley C, Mikoulitch I, Cavanagh C, Edwards KJ, Hayden M, Akhunov E (2014) Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90,000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol J 12:787–796

Yang J, Zhu J, Williams RW (2007) Mapping the genetic architecture of complex traits in experimental populations. Bioinformatics 23:1527–1536

Young ND (1996) QTL mapping and quantitative disease resistance in plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 34:479–501

Acknowledgements

Financial support was received from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, the Western Grains Research Foundation and the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund. Technical and field support from the Swift Current Research and Development Centre wheat breeding and molecular genetic technical staff is greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RDC and REK were involved in conceptualization. RDC and REK were involved in funding acquisition and project administration. RDC, REK, YR, CJP and AGS provided the resources. FEB, RDC, REK and HLC contributed to data curation. FEB, REK, AN, HLC and AS contributed to formal data analysis and interpretation. FEB, REK, RDC, HLC and AS wrote the original draft. FEB, RDC, REK, AS, HLC, CJP, AN, AGS and YR wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Xiaoquan Qi.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bokore, F.E., Cuthbert, R.D., Knox, R.E. et al. Mapping quantitative trait loci associated with common bunt resistance in a spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) variety Lillian. Theor Appl Genet 132, 3023–3033 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-019-03403-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-019-03403-3