Abstract

Solanum × michoacanum (Bitter.) Rydb. is a diploid, 1 EBN (Endosperm Balance Number) nothospecies, a relative of potato originating from the area of Morelia in Michoacán State of Mexico that is believed to be a natural hybrid of S. bulbocastanum × S. pinnatisectum. Both parental species and S. michoacanum have been described as sources of resistance to Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary. The gene for resistance to potato late blight, Rpi-mch1, originating from S. michoacanum was mapped to the chromosome VII of the potato genome. It confers high level of resistance since the plants possessing it showed only small necrotic lesions or no symptoms of the P. infestans infection and we could ascribe over 80% of variance observed in the late blight resistance test of the mapping population to the effect of the closest marker. Its localization on chromosome VII may correspond to the localization of the Rpi1 gene from S. pinnatisectum. When mapping Rpi-mch1, one of the first genetic maps made of 798 Diversity Array Technology (DArT) markers of a plant species from the Solanum genus and the first map of S. michoacanum, a 1EBN potato species was constructed. Particular chromosomes were identified using 48 sequence-specific PCR markers, originating mostly from the Tomato-EXPEN 2000 linkage map (SGN), but also from other sources. Recently, the first DArT linkage map of 2 EBN species Solanum phureja has been published and it shares 197 DArT markers with map obtained in this study, 88% of which are in the concordant positions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Solanum × michoacanum (Bitter.) Rydb. is a diploid, 1 EBN (Endosperm Balance Number) nothospecies, a relative of potato originating from the area of Morelia in Michoacán State of Mexico. Damp grassy fields amongst rocks, elevated 2000–2100 m above the sea level (Hawkes 1990) or areas of tropical deciduous forest among grasses, shrubs and cacti of old lava fields (website: Solanaceae Source—Natural History Museum) are its habitats. On the basis of morphology and experimental crosses, it is believed to be a natural hybrid of S. bulbocastanum × S. pinnatisectum, both of which naturally occur in the same region (Hawkes 1990). It was included into “diploid Mexican group” together with both parental species according to genetic diversity revealed by AFLP markers (Jacobs et al. 2008). However, in another study, alternative hypotheses that S. michoacanum is not a hybrid species at all or that it is a hybrid between S. bulbocastanum and S. trifidum, were also formed on the basis of genetic analyses with use of AFLP (Vriesendorp et al. 2007).

Both species generally assumed to be the parents of S. michoacanum and S. michoacanum have been described as sources of resistance to the potato pathogen, Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary and although neither of them can be directly crossed to potato, S. bulbocastanum has been widely exploited in potato breeding programs.

Clones highly resistant to P. infestans in detached leaflet test as well as the susceptible ones were identified within an accession of S. michoacanum VIR5763 and similar variation in tuber resistance was also noted (Jakuczun and Wasilewicz-Flis 2004a). The only documented effort to overcome the crossing barrier between S. michoacanum and S. tuberosum was through somatic hybridization, which resulted in obtaining several hybrids, three of them with enhanced late blight resistance (Szczerbakowa et al. 2010). Apart from the late blight resistance, clones that are suitable for the potato crisps production (Jakuczun and Wasilewicz-Flis 2004b) and resistant to the green peach aphid were also found within S. michoacanum (Radcliffe et al. 1974).

A major late blight resistance locus Rpi1 was identified in the S. pinnatisectum and mapped to potato chromosome VII using an interspecific cross with S. cardiophyllum (Kuhl et al. 2001). Later, as a starting point to cloning of this gene, two BAC libraries were constructed from S. pinnatisectum and four markers linked to the Rpi1 gene were hybridized to 14 BAC clones of these libraries (Chen et al. 2004). So far, the sequence of this gene has not been published. However, several attempts to exploit the resistance in S. pinnatisectum have been undertaken. A single aneuploid hybrid between S. pinnatisectum and S. tuberosum was obtained by double pollination and embryo rescue and it was shown to be resistant to late blight (Ramon and Hanneman 2002). Somatic hybridization has been used successfully several times in order to transfer late blight resistance from S. pinnatisectum to S. tuberosum (Thieme et al. 1997; Szczerbakowa et al. 2005; Greplová et al. 2008; Polzerová et al. 2010), although only one of the obtained resistant hybrids was further backcrossed to S. tuberosum (Thieme et al. 1997). S. pinnatisectum is also a source of resistance to Colorado potato beetle (Chen et al. 2003, 2004; Nandy et al. 2008) and tuber soft rot caused by Pectobacterium carotovorum (syn. Erwinia carotovora ssp. carotovora) (Hawkes 1994).

So far, four R genes for late blight resistance have been cloned from S. bulbocastanum. The fifth one, Rpi-abpt is likely, but not definitely originating from this species (Park et al. 2005b). The first S. bulbocastanum R gene for P. infestans resistance was identified on potato chromosome VIII, independently by two research groups. Under the name RB, it was mapped (Naess et al. 2001) and cloned (Song et al. 2003) using BC2 populations derived from somatic hybrids (Helgeson et al. 1998). The same gene, named Rpi-blb1, was cloned using an F1 population of the intraspecific S. bulbocastanum cross (van der Vossen et al. 2003). A highly similar gene originating from the same species, Rpi-bt1, was mapped also to the potato chromosome VIII and then cloned (Oosumi et al. 2009). The Rpi-blb2 gene was mapped on chromosome VI in several tetraploid backcrosses resulting from complex bridge crossing named ABPT (Hermsen and Ramanna 1973) that involved S. acaule, S. bulbocastanum, S. phureja and S. tuberosum and then cloned using the intraspecific cross (van der Vossen et al. 2005). Two other genes, Rpi-blb3 and Rpi-abpt (Hermsen and Ramanna 1973) were mapped to potato chromosome IV (Park et al. 2005a, b) and also subsequently cloned (Lokossou et al. 2009). The materials from the bridge crossing mentioned above were involved in the potato breeding programs that yielded at least four cultivars: Biogold, Bionica, Kibama and Kisoro (website: Potato Pedigree Database, Wageningen University). The genes Rpi-blb1 and Rpi-blb2 are also being introduced into potato cultivars via cisgenesis (website: SeedQuest: Deliberate release into the E.U. environment of GMOs). Somatic hybridization was another method quite frequently applied for obtaining hybrids between S. bulbocastanum and S. tuberosum resistant to P. infestans (Thieme et al. 1997; Helgeson et al. 1998; Szczerbakowa et al. 2003; Bołtowicz et al. 2005; Greplová et al. 2008), but so far, this approach has not resulted in cultivar registration.

Since the resistance to P. infestans of both S. pinnatisectum and S. bulbocastanum is well known and a number of R genes have been identified in these species, S. michoacanum seemed to be a promising source of this trait. The goal of this study was to characterize the late blight resistance in an intraspecific S. michoacanum cross and to map the underlying R gene, named Rpi-mch1.

Materials and methods

Plant material

A resistant clone 99-12/8 and a susceptible clone 99-12/12 selected from the S. michoacanum accession VIR5763 were crossed to obtain an F1 mapping population of 164 individuals. Along with the mapping population and the parental clones, five standard cultivars: Eersteling, Tarpan (susceptible to late blight), Bzura (resistant, possessing R1 and an unidentified other R gene), Escort [resistant, with R1, R2, R3 and R10 (Bormann et al. 2004)] and Robijn (moderately resistant to P. infestans) were included in tests of resistance to P. infestans.

Phytophthora infestans isolates

A preliminary test on S. michoacanum parental clones and potato cultivars Tarpan and Bzura was performed in order to choose P. infestans isolates that can differentiate best the resistant and the susceptible parent (Table 1). In 2009, the isolates MP585 and MP847 were tested, and in 2010 so were the isolates MP717, MP778, MP919, MP920, MP921 and MP1161. Some characteristics of these isolates are shown in Table 1. All the tested P. infestans isolates originate from Poland and belong to the IHAR-PIB Młochów Research Centre collection. Two chosen isolates were used in the late blight resistance tests of the mapping population: MP847 in 2009 and MP921 in 2010. The MP847 was isolated in 2007 in Boguchwała near Rzeszów, Poland, from the potato cv. Lawina, while the MP921 was collected in 2008 in Młochów near Warszawa, Poland, from the potato cv. Alicja. Both isolates were of A2 mating type and Ia mitochondrial haplotype, sensitive to metalaxyl, race: 1.3.4.7.10.11 but only MP921 was able to infect cv. Bzura to some extent (Table 1). The P. infestans cultures were stored in vitro on rye A agar slopes (Griffith et al. 1995) covered with mineral oil, in darkness at 5°C. They were propagated and maintained for a short-term also on rye A medium, in Petri dishes kept in darkness at 16°C. In all resistance tests a set of Black’s differentials obtained from Scottish Agricultural Science Agency, Edinburgh, UK was used to monitor the effective virulence of P. infestans isolates. Before each resistance test, the isolate was multiplied at least twice on susceptible potato tissue.

Late blight resistance assessment

The resistance of the parental clones, mapping population and standard cultivars to P. infestans was evaluated in two subsequent years 2009 and 2010 by the laboratory detached leaf test. The fully expanded leaves were detached from 6-week-old greenhouse-grown plants and placed on wet wood wool with the abaxial side up. They were inoculated by spraying with the sporangia and zoospore suspension (50 sporangia/μl) similarly as described by Kuhl et al. (2001). Next day the leaves were turned over, the adaxial side up. After 4 days of incubation in conditions supportive for disease development (high relative humidity, 16°C and constant light of about 1,600 lx), six leaflets per leaf (three pairs adjacent to the terminal leaflet) were scored separately in a 1–9 scale, where 9 was the most resistant (Śliwka et al. 2007). In 2009, the test with the P. infestans isolate MP847 was performed on two dates and each time two replications × two leaves × six leaflets per genotype were scored giving in total 48 leaflets evaluated per genotype. In 2010, the test with the isolate MP921 was done on three different dates and each time two replications × one leaf × six leaflets per genotype (36 leaflets in total) were scored. A genotype was considered resistant, i.e. possessing the R gene, when its mean resistance score was ≥6.

DNA isolation, sequence-specific markers

Genomic DNA was extracted from 1 g of fresh, young leaves of greenhouse grown plants with the DNeasy Plant Maxi kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). All sequence-specific markers listed in ESM 1 were amplified using the following conditions. The reaction mixture of 20 μl contained 2 μl of 10× PCR buffer, the four deoxynucleotides (0.1 mM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), MgCl2 (1.5 mM; Invitrogen™ by Life Technologies™), primers (0.2 μM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), Taq polymerase (0.05U/μl; Invitrogen™ by Life Technologies™) and 10–30 ng of the template DNA. The PCR program was: 94°C–180 s; 40 cycles of: 94°C–30 s, 55°C–45 s, 72°C–90 s; 72°C–420 s, if the annealing temperature was modified, it has been marked in ESM 1. The reactions of PCR products with corresponding restriction endonucleases (Fermentas Life Sciences, Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc.), also listed in ESM 1, were performed according to the producer’s recommendations.

Diversity Array Technology

The analyses were performed by Diversity Array Pty Ltd. Canberra, Australia. The process of DArT marker discovery involved construction of 18 bacterial clone libraries using methods described by Wenzl et al. (2004), ranging in size from 384 to 4,992 clones and totalling 23,040 clones. These clones were tested for polymorphism using several hundred potato accessions and 7,680 most polymorphic markers were selected for re-arraying into a genotyping array. Each clone on the array was printed in duplication using equipment and methods described recently in detail by Sansaloni et al. (2010).

Genomic complexity reduction method is a critical component of DArT technology, selecting reproducibly the low copy fraction of a plant genome (Jaccoud et al. 2001). It usually involves using “methyl filtration” with PstI Restriction Enzyme (RE) in combination with a frequently cutting, methylaton independent RE. After a number of tests performed in the preliminary experiment (data not presented) the PstI/TaqI method was selected for potato marker discovery. The assay involving restriction digestion reaction combined with adaptor ligation followed by PCR amplification of the intact (and relatively small) PstI fragments used methodology described by Akbari et al. (2006). Prior to performing the assay each DNA sample was tested for presence of DNAses through incubation with RE buffer for 2 h at 37°C. After passing this QC test each sample was processed in the same manner and resulting PCR products were run on 1.2% agarose gel to verify uniform digestion and amplification.

All successful amplification products were labelled with either Cy3 or Cy5 fluorescent dye and hybridised to the array developed by international potato-DArT consortium.

After overnight hybridisation at 63°C the slides were washed and scanned on Tecan LS300 scanner as reported by Akbari et al. (2006). Feature identification and marker classification was performed by DArTsoft version 7.4.4 developed by DArT Pty Ltd. (website: Diversity Array Technology Software). Binary (0/1) scores were used for map construction.

Statistical and linkage analyses

The categorization of the individuals of the mapping population into classes of resistant and susceptible ones was done on the basis of weighted mean leaflet resistance (2009–2010) because of different numbers of leaflets tested in each year. Fitness to the normal distribution of the phenotypic data was checked by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The reproducibility of the resistance tests between the years was evaluated by linear Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Marker-trait linkages and determination coefficients (R 2) were estimated by the Student’s t test and analysis of variance, respectively. Fitness of segregation to the expected ratio was checked by the χ2 test. All statistical analyses were performed using computer program STATISTICA for Windows (Stat Soft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Linkage analyses were performed using JoinMap® 4 (Van Ooijen 2006) with following settings: CP population type (creating of maternal and paternal linkage maps first and then creating a common population map), independence LOD as a grouping parameter (linkages with LOD > 3 were considered significant), regression mapping algorithm and Haldane’s mapping function.

Results

Late blight resistance assessment

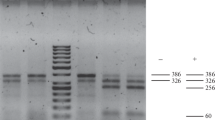

Parent 99-12/8 was resistant and parent 99-12/12 was susceptible to both P. infestans isolates used in 2 years of testing. In 2009 (P. infestans isolate MP847) mean scores of clones 99-12/8 and 99-12/12 were 7.6 and 1.0, respectively, while in 2010 (isolate MP921) the clones 99-12/8 and 99-12/12 were scored 7.3 and 1.4, respectively. Mean scores of the standard cultivars were according to the expectations and as follows: Eersteling (2009-3.2, 2010-6.2) and Tarpan (2.6, 5.8) were susceptible, Bzura (9.0, 7.8) and Escort (9.0 in both years) were resistant and Robijn (5.3, 6.0) was moderately resistant to P. infestans. Although the infection of the susceptible cultivars in 2010 was weak, the infection pressure estimated as mean score of all progeny, parents and standards was stronger in 2010 (score 3.5) than in 2009 (4.1). The mean results of the late blight resistance tests obtained for progeny in 2009 and 2010 were strongly correlated, with Pearson’s correlation coefficient r = 0.863, P < 0.000. Analysis of variance showed significant effects of genotype, year, genotype × year interaction and year × date interaction on the resistance (Table 2). The genotype had the strongest influence on the resistance results explaining more than 76% of variance observed in the results (Table 2). Distributions of mean late blight resistance scores of the mapping population obtained in 2009 and 2010 deviated significantly from the normal distribution (Fig. 1) which was confirmed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The range of late blight grades observed in the mapping population was 1.0–9.0. The division of these results into two classes of resistant (mean score ≥ 6) and susceptible ones (mean score < 6) was clearly noticeable in both 2009 and 2010, although it was sharper in 2009 (Fig. 1a). When weighted mean resistance result from both years was taken into account, 59 individuals from the mapping population were scored as resistant and 105 individuals were susceptible. That ratio is significantly deviated (χ 2 = 12.90, df = 1, P < 0.000) from the 1:1 ratio expected under the assumption that a single resistant gene is segregating in this population. However, it is not significantly different from 1: 2 ratio (χ 2 = 0.51, df = 1, P < 0.473) indicating rather segregation distortion than the effect of other gene(s).

Distributions of mean leaflet resistance to P. infestans in whole leaf tests performed with the isolate MP847 in 2009 (a) and with the isolate MP921 in 2010 (b) in the mapping population of S. michoacanum. The resistance was assessed in 1–9 scale, where 9 means the most resistant. The fitness to the normal curve: K−S Kolmogorov−Smirnov test, d – coefficient calculated for this test, p – probability, the line indicates the normal curve. Resistance levels of parental clones are marked with their names: 99-12/8 and 99-12/12

Linkage map

The linkage map of S. michoacanum was constructed of 846 dominant markers, including 51 sequence-specific reference markers listed in ESM 1 and 792 DArT markers. Using both marker types and the JoinMap® 4, we obtained maternal and paternal genetic maps consisting of 12 linkage groups each (not shown). In a next stage, a common CP linkage map was made for 11 chromosomes, with an exception of chromosome VII, where due to a small number of markers (28), it was not possible (ESM 2). While only markers inherited from either 99-12/8 or 99-12/12 were assembled into, respectively, maternal and paternal map, the common CP map was enriched with large number of dominant markers which in both parents were in a heterozygous state. Within 51 sequence-specific reference markers, two marker bands derived from the PCR fragment C2_At3g15430 (SGN) were mapped to a different chromosome than expected (chromosome II instead of VII) and one marker, GP78 (Śliwka et al. 2007) was scored but not mapped. The remaining 48 reference markers were paired in an expected manner, i.e. the each two of them derived from the same parent and from the same of the 12 chromosomes were linked together, which allowed us to identify the obtained linkage groups (ESM 2, Table 3). The order of the sequence-specific markers in most of the cases i.e. on chromosomes I, II, III, IV, VII, VIII, IX, X (SGN) and XII (GABI) corresponded well to the order on reference maps. There were the following exceptions: on chromosome V two markers inherited from different parents but derived from the same PCR fragment U227536 digested with two different endonucleases (ESM1) mapped to different positions 48 cM apart (ESM2); on chromosome VI markers C2_At2g28690, C2_At2g39690 and Mi closely linked on Tomato-EXPEN 2000 map (SGN: 3.7 cM, 5.3 cM and 5.5 cM, respectively) were further apart and in a different order on S. michoacanum map; markers C2_At1g07960 and C2_At2g28490 (Tomato-EXPEN 2000 map: 82.5 and 98 cM, respectively) from chromosome XI mapped to a different chromosome arm than expected (ESM2).

The total length of the S. michoacanum genetic map reached 1,047 cM. The length of particular chromosomes varied from 54.5 cM (chromosome XI) to 128.2 (chromosome VI) with the average value of 87.3 cM (Table 3). Chromosome I was one of longest but also the richest in markers, with 133 markers located on this chromosome, while the smallest number of markers (28) was mapped to the two parental linkage groups corresponding to the chromosome VII. The average number of markers per chromosome was 70.25 (Table 3). The theoretical mean interval calculated as the total map length (in cM) divided by the total number of markers was 1.2 cM and differed from the observed mean interval, calculated as a mean value of all intervals between the markers, that reached 2.2 cM, which indicated that the markers were not distributed evenly. The highest marker density was on chromosome VIII, where the observed mean interval between markers was 0.7 cM. The biggest observed mean interval between markers was 10.4 cM on chromosome VII of the clone 99-12/8.

The Rpi-mch1 gene

A resistance gene against potato late blight was mapped on chromosome VII of the resistant parent 99-12/8 (Fig. 2). Only five DArT markers and two sequence-specific markers mapped to the same linkage group and all of them were located on the same side of the gene (ESM2). Three markers showed statistically significant linkage with the trait confirmed by the T test (Table 4). These marker-trait associations were highly significant irrespective of the year of testing and the isolate used for testing the resistance to P. infestans and were also clear when mean weighted resistance was taken into account (Table 4). The CAPS marker C2_At1g53670 (Fig. 3) was the closest to the gene and located 5.7 cM from it. Its effect explained 82.7% of variance observed in phenotypic resistance assessment in 2009, when the P. infestans isolate MP847 was applied and 67.6% in 2010 when the isolate MP921 was used (Table 4).

Discussion

A gene for resistance to potato late blight, Rpi-mch1, originating from S. michoacanum was mapped to the chromosome VII of the potato genome. It is a gene which confers high level of resistance since the plants possessing it showed only small necrotic lesions or no symptoms of the P. infestans infection. Its localization on chromosome VII possibly corresponds to the localization of the Rpi1 gene from S. pinnatisectum (Kuhl et al. 2001) and it could be a second gene for resistance to P. infestans mapped in this region, although the lack of flanking markers prevents us from drawing conclusions. This position would be in a good agreement with the hypothesis that S. michoacanum is a natural hybrid of S. pinnatisectum and S. bulbocastanum (Hawkes 1990) and we still cannot exclude that both genes are homologous or even identical. Similarly to Kuhl et al. (2001) we noted in the mapping population resistance segregation ratio skewed towards the susceptibility, although in case of S. michoacanum population it was stronger. Even though in the Polish P. infestans population we find isolates that are virulent to the Rpi-mch1 gene, it could be used in potato breeding, especially in the resistance gene pyramids with other R genes, if only the crossing barrier were overcome. Within the eight P. infestans isolates that were tested on the parents of the S. michoacanum mapping population (Table 1), two were compatible (MP778 and MP1161), while the rest did not cause sporulating lesions on the leaves of the resistant parent, 99-12/8. On the basis of the virulence of these isolates we can conclude that the Rpi-mch1 virulence spectrum might be similar or equal to the one conferred by R8 and/or R9 genes from S. demissum (Table 1) which also resembles the spectrum of the Rpi1 gene (Kuhl et al. 2001). Several other resistance loci have been mapped in various Solanum species within the same chromosomal segment as Rpi-mch1 and Rpi1 genes. Among them there are Gro1 gene for resistance to Globodera rostochiensis originating from S. spegazzinii (Barone et al. 1990), I1 and I3 genes from S. pennellii for resistance to Fusarium oxysporum (Sarfatti et al. 1991, Bournival et al. 1989) as well as potato QTL for resistance to Erwinia carotovora ssp. atroseptica (Zimnoch-Guzowska et al. 2000) and potato QTL for late blight resistance (Leonards-Schippers et al. 1994), indicating once again the tendency of resistance loci to cluster.

When mapping Rpi-mch1, we constructed one of the first genetic maps made of DArT markers of a plant from the Solanum genus and the first map of S. michoacanum, a 1EBN potato species. We identified particular chromosomes using sequence-specific PCR markers, originating mostly from the Tomato-EXPEN 2000 linkage map (SGN), but also from other sources (ESM 1). The first mapping of 1EBN Solanum species, S. bulbocastanum, with the use of DArT markers resulted in obtaining 12 linkage groups consisting of 439 markers with a total map length of 403 cM. However, those linkage groups have not been assigned to the potato chromosomes, so far (Mann et al. 2011). Recently, the first DArT linkage map of 2 EBN Solanum species has been published: Solanum phureja diploid map 2010 (SGN), which enabled comparison between this map and ours (ESM 2, Table 3). The S. phureja diploid map 2010 consists of 2530 markers, including 1827 DArT markers, 316 Simple Sequence Repeat markers and 387 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Out of 197 DArT markers that were common for both maps, 173 (88%) were in corresponding positions on both maps and 24 (12%) in discordant positions (ESM 2). Most of the common and concordant markers were located on chromosomes VIII, IX, I, II, III and IV, ranging from 17 to 41 per particular chromosome. On remaining chromosomes we found 1–3 DArT markers in positions concordant with the Solanum phureja diploid map 2010 (SGN). On chromosomes I, II, III, VII, IX, XI and XII we mapped 24 DArT markers that were located on different chromosomes on the S. phureja diploid map 2010 (SGN). Ten of them, located on chromosome III of S. michoacanum, were dispersed over chromosomes II, VII, X and XI of the Solanum phureja diploid map 2010 (SGN). The causes of this discrepancy could be either genuine differences between the genomes of these two distant Solanum species or mapping errors. Although the overall quality and resolution of the S. michoacanum linkage map obtained in this study was good (846 markers, 1,047 cM) in comparison to other genetic maps of diploid potato (Bonierbale et al. 1988; Kuhl et al. 2001; Costanzo et al. 2005; van Os et al. 2006), the chromosome VII that harboured the Rpi-mch1 gene was poor in polymorphic and segregating markers. Moreover, both the Rpi-mch1 gene and the linked markers showed strong distortion in segregation. That may be caused by the local suppression of recombination due to the hybrid nature of S. michoacanum. Reduction of recombination and distorted segregation was observed before in other interspecific Solanum hybrid obtained from the cross S. tuberosum × S. spegazzinii (Kreike and Stiekema 1997). Another explanation could be that while the DArT platform used in this study was developed using clones derived from cultivated potato genomes and S. michoacanum chromosome VII differed possibly more than the other chromosomes from the S. tuberosum ones, we were able to map only a few markers in this region of the genome. Nevertheless, the CAPS marker C2_At1g53670 that was mapped 5.7 cM from the Rpi-mch1 gene can be a useful tool for tracking the gene, for example in somatic hybrids with potato, as it was in case of the marker GP94 applied for selection of potatoes with another late blight resistance gene Rpi-phu1 that was located in 6.4 cM distance (Śliwka et al. 2010).

The results obtained in this study will be exploited further in several ways. We plan to enhance map resolution of S. michoacanum chromosome VII using DArT markers derived from a panel of wild Solanum species. The mapping data can support the transfer of the Rpi-mch1 gene into cultivated potato gene pool through marker-assisted selection of the resistant somatic hybrids S. michoacanum + S. tuberosum, and such work is in progress in our group. They can also be helpful in cloning of the Rpi-mch1 gene and its subsequent transfer via cisgenesis into potato cultivars which can widen the pool of the late blight resistance genes available for potato breeding. That can enable building R gene pyramids which seem to be a promising strategy for obtaining potato cultivars highly and durably resistant to P. infestans.

References

Akbari M, Wenzl P, Caig V, Carling J, Xia L, Yang S, Uszynski G, Mohler V, Lehmensiek A, Kuchel H, Hayden M, Howes N, Sharp P, Vaughan P, Rathmell B, Huttner E, Kilian A (2006) Diversity arrays technology (DArT) for high-throughput profiling of the hexaploid wheat genome. Theor App Genet 113:1409–1420

Barone A, Ritter E, Schachtschabel U, Debener T, Salamini F, Gebhardt C (1990) Localization by restriction fragment length polymorphism mapping in potato of a major dominant gene conferring resistance to the potato cyst nematode Globodera rostochiensis. Mol Gen Genet 224:177–182

Bołtowicz D, Szczerbakowa A, Wielgat B (2005) RAPD analysis of the interspecific somatic hybrids Solanum bulbocastanum (+) S. tuberosum. Cell Mol Biol Lett 10:151–162

Bonierbale MW, Plaisted RL, Tanksley RD (1988) RFLP maps based on a common set of clones reveal modes of chromosomal evolution in potato and tomato. Genetics 120:1095–1103

Bormann CA, Rickert AM, Castillo Ruiz RA, Paal J, Lübeck J, Strahwald J, Buhr K, Gebhardt C (2004) Tagging quantitative trait loci for maturity-corrected late blight resistance in tetraploid potato with PCR-based candidate gene markers. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 17:1126–1138

Bournival BL, Scott JW, Vallejos CE (1989) An isozyme marker for resistance to race 3 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici in tomato. Theor Appl Genet 78:489–494

Chen X, Salamini F, Gebhardt C (2001) A potato molecular-function map for carbohydrate metabolism and transport. Theor Appl Genet 102:284–295

Chen Q, Kawchuk LM, Lynch DR, Goettel MS, Fujimoto DK (2003) Identification of late blight, Colorado potato beetle and blackleg resistance in three Mexican and two South American wild 2× (1EBN) Solanum species. Am J Potato Res 80:9–19

Chen Q, Sun S, Ye Q, McCuine, Huff E, Zhang H-B (2004) Construction of two BAC libraries from the wild Mexican diploid potato, Solanum pinnatisectum, and the identification of clones near the late blight and Colorado beetle resistance loci. Theor Appl Genet 108:1002–1009

Costanzo S, Šimko I, Christ BJ, Haynes KG (2005) QTL analysis of late blight resistance in a diploid potato family of Solanum phureja × S. stenotomum. Theor Appl Genet 111:609–617

Greplová M, Polzerová H, Vlastniková H (2008) Electrofusion of protoplasts from Solanum tuberosum, S. bulbocastanum and S. pinnatisectum. Acta Physiol Plant 30:787–796

Griffith GW, Snell R, Shaw DS (1995) Late blight (Phytophthora infestans) on tomato in the tropics. Mycologist 9:87–98

Hawkes JG (1990) The potato, evolution, biodiversity and genetic resources. Belhaven Press, London

Hawkes JG (1994) Origin of cultivated potatoes and species relationships. In: Bradshaw JE, Mackay GR (eds) Potato genetics. CAB International, Wallingford, pp 3–42

Helgeson JP, Pohlman JD, Austin S, Haberlach GT, Wielgus SM, Ronis D, Zambolim L, Tooley P, McGrath JM, James RM, Stevenson WK (1998) Somatic hybrids between Solanum bulbocastanum and potato: a new source of resistance to late blight. Theor Appl Genet 96:738–742

Hermsen JGTH, Ramanna MS (1973) Double-bridge hybrids of Solanum bulbocastanum and cultivars of Solanum tuberosum. Euphytica 22:457–466

Jaccoud D, Peng K, Feinstein D, Kilian A (2001) Diversity arrays: a solid state technology for sequence information independent genotyping. Nucleic Acid Res 29:E25

Jacobs MMJ, van den Berg RG, Vleeshouwers VGAA, Visser M, Mank R, Sengers M, Hoekstra R, Vosman B (2008) AFLP analysis reveals a lack of phylogenetic structure within Solanum section Petota. BMC Evol Biol 8:145–157

Jakuczun H, Wasilewicz-Flis I (2004a) New sources of potato resistance to Phytophthora infestans at the diploid level. Plant Breed Seed Sci 50:137–145

Jakuczun H, Wasilewicz-Flis I (2004b) Ziemniak diploidalny źródłem cech jakościowych w hodowli. Zesz Prob Nauk Roln 500:127–136 (in Polish)

Kreike CM, Stiekema WJ (1997) Reduced recombination and distorted segregation in a Solanum tuberosum (2x) × S. spegazzinii (2x) hybrid. Genome 40:180–187

Kuhl JC, Hanneman RE Jr, Havey MJ (2001) Characterization and mapping of Rpi1, a late-blight resistance locus from diploid (1EBN) Mexican Solanum pinnatisectum. Mol Genet Genomics 265:977–985

Leonards-Schippers C, Gieffers W, Schäfer-Pregl R, Ritter E, Knapp SJ, Salamini F, Gebhardt C (1994) Quantitative resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato: A case study for QTL mapping in an allogamous plant species. Genetics 137:67–77

Lokossou AA, Park T-H, van Arkel G, Arens M, Ruyter-Spira C, Morales J, Whisson SC, Birch PRJ, Visser RGF, Jacobsen E, van der Vossen EAG (2009) Exploiting knowledge of R/Avr genes to rapidly clone a new LZ-NBS-LRR family of late blight resistance genes from potato linkage group IV. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22:630–641

Mann H, Iorizzo M, Gao L, D’Agostino N, Carputo D, Chiusano ML, Bradeen JM (2011) Molecular linkage maps: strategies, resources and achievements. In: Bradeen JM, Kole C (eds) Genetics, genomics and breeding of crop plants: potato. Science Publishers and CRC Press, UK, pp 68–89

Naess SK, Bradeen JM, Wielgus SM, Haberlach GT, McGrath JM, Helgeson JP (2001) Analysis of the introgression of Solanum bulbocastanum DNA into potato breeding lines. Mol Gen Genom 265:694–704

Nandy S, Chen Q, Yang JL, Goettel M (2008) Genetic architecture of genes from the wild potato plant (Solanum pinnatisectum) showing resistance to Colorado potato beetle. Aust J Crop Sci 2:49–56

Oosumi T, Rockhold DR, Maccree MM, Deahl KL, McCue KF, Belknap WR (2009) Gene Rpi-bt1 from Solanum bulbocastanum confers resistance to late blight in transgenic potatoes. Am J Pot Res 86:456–465

Park T-H, Gros J, Sikkema A, Vleeshouwers VGAA, Muskens M, Allefs S, Jacobsen E, Visser RGF, van der Vossen EAG (2005a) The late blight resistance locus Rpi-blb3 from Solanum bulbocastanum belongs to a major late blight R gene cluster on chromosome 4 of potato. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18:722–729

Park T-H, Vleeshouwers VGAA, Hutten RCB, van Eck HJ, van der Vossen EAG, Jacobsen E, Visser RGF (2005b) High-resolution mapping and analysis of the resistance locus Rpi-abpt against Phytophthora infestans in potato. Mol Breeding 16:33–43

Park T-H, Foster S, Brigneti G, Jones JDG (2009) Two distinct potato late blight resistance genes from Solanum berthaultii are located on chromosome 10. Euphytica 165:269–278

Polzerová H, Patzak J, Greplová (2010) Early characterization of somatic hybrids from symmetric protoplast electrofusion of Solanum pinnatisectum Dun. And Solanum tuberosum L. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 104:163–170

Radcliffe EB, Lauer FI, Stucker RE (1974) Stability of green peach aphid resistance in tuber-bearing Solanum introductions and its effect on screening procedures. Environ Entomol 3:1022–1026

Ramon M, Hanneman RE (2002) Introgression of resistance to late blight (Phytophthora infestans) from Solanum pinnatisectum into S. tuberosum using embryo rescue and double pollination. Euphytica 127:421–435

Sansaloni CP, Petroli CD, Carling J, Hudson CJ, Steane DA, Myburg AA, Grattapaglia D, Vaillancourt RE, Kilian A (2010) A high-density Diversity Arrays Technology (DArT) microarray for genome-wide genotyping in Eucalyptus. Plant Methods 6:16

Sarfatti M, Abu-Abied M, Katan J, Zamir D (1991) RFLP mapping of I1, a new locus in tomato conferring resistance against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 1. Theor Appl Genet 82:22–26

Śliwka J, Jakuczun H, Lebecka R, Marczewski W, Gebhardt C, Zimnoch-Guzowska E (2007) Tagging QTLs for late blight resistance and plant maturity from diploid wild relatives in a cultivated potato (Solanum tuberosum) background. Theor Appl Gen 115:101–112

Śliwka J, Jakuczun H, Kamiński P, Zimnoch-Guzowska E (2010) Marker-assisted selection of diploid and tetraploid potatoes carrying Rpi-phu1, a major gene for resistance to Phytophthora infestans. J Appl Genet 51:133–140

Song J, Bradeen JM, Naess SK, Raasch JA, Wielgus SM, Haberlach JT, Liu J, Kuang H, Austin-Phillips S, Buell CR, Helgeson JP, Jiang J (2003) Gene RB cloned from Solanum bulbocastanum confers broad spectrum resistance to potato late blight. PNAS 100:9128–9133

Szczerbakowa A, Bołtowicz D, Wielgat B (2003) Interspecific somatic hybrids Solanum bulbocastanum (+) S. tuberosum H-8105. Acta Physiol Plant 25:365–373

Szczerbakowa A, Bołtowicz D, Lebecka R, Radomski P, Wielgat B (2005) Characteristics of the interspecific somatic hybrids Solanum pinnatisectum (+) S. tuberosum H-8105. Acta Physiol Plant 27:317–325

Szczerbakowa A, Tarwacka J, Oskiera M, Jakuczun H, Wielgat B (2010) Somatic hybridization between the diploids of S. × michoacanum and S. tuberosum. Acta Physiol Plant 32:867–873

Thieme R, Darsow U, Gavrilenko T, Dorokhov D, Tiemann H (1997) Production of somatic hybrids between S. tuberosum L. and late blight resistant Mexican wild potato species. Euphytica 97:189–200

Van der Vossen EAG, Sikkema A, Hekkert BL, Gros J, Stevens P, Muskens M, Wouters D, Pereira A, Stiekema W, Allefs S (2003) An ancient R gene from the wild potato species Solanum bulbocastanum confers broad-spectrum resistance to Phytophthora infestans in cultivated potato and tomato. Plant J 36:867–882

Van der Vossen JE, Sikkema A, Muskens M, Wouters D, Wolters P, Pereira A, Allefs S (2005) The Rpi-blb2 gene from Solanum bulbocastanum is an Mi-1 gene homolog conferring broad-spectrum late blight resistance in potato. Plant J 44:208–222

Van Ooijen JW (2006) JoinMap® 4, Software for the calculation of the genetic linkage maps in experimental populations. Kyazma B.V., Wageningen, Netherlands

Van Os H, Andrzejewski S, Bakker E, Barrena I, Bryan GJ, Caromel B, Ghareeb B, Isidore E, de Jong W, van Koert P, Lefebvre V, Milbourne D, Ritter E, Rouppe van der Voort JNAM, Rousselle-Bourgeois F, van Vliet J, Waugh R, Visser RGF, Bakker J, van Eck HJ (2006) Construction of a 10, 000-marker ultradense genetic recombination map of potato: providing a framework for accelerated gene isolation and a genomewide physical map. Genetics 173:1075–1087

Vriesendorp B, Vrielink-van Ginkel M, van den Berg RG 2007 AFLPs and hybrid detection—a case study of Solanum. Wageningen University PhD thesis: Phylogenetworks. Exploring reticulate evolution and its consequences for phylogenetic reconstruction, pp 103-124

Wenzl P, Kudrna D, Jaccoud D, Huttner E, Kleinhofs A, Kilian A (2004) Diversity arrays technology (DArT) for whole genome profiling of barley. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:9915–9920

Witek K, Strzelczyk-Żyta D, Hennig J, Marczewski W (2006) A multiplex PCR approach to simultaneously genotype potato towards the resistance alleles Ry-f sto and Ns. Mol Breed 18:273–275

Zimnoch-Guzowska E, Marczewski W, Lebecka R, Flis B, Schafer-Pregl R, Salamini F, Gebhardt C (2000) QTL analysis of new sources of resistance to Erwinia carotovora ssp. atroseptica in potato done by AFLP, RFLP, and resistance-gene-like markers. Crop Sci 40:1156–1167

Diversity Array Technology Software: http://www.diversityarrays.com/software.html#dartsoft

Potato Pedigree Database, Wageningen University: http://www.plantbreeding.wur.nl/potatopedigree/

SeedQuest - Central information website for the global seed industry: Deliberate release into the E.U. environment of GMOs for any other purposes than placing on the market: Potato with improved resistance to Phytophthora infestans - BASF Plant Science GmbH 2005 http://www.seedquest.com/News/releases/2005/october/13818.htm

SOL Genomics Network (SGN) Database http://solgenomics.net/

Solanaceae Source - Natural History Museum http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/solanaceaesource/

Acknowledgments

The work described here was financed by The National Centre for Research and Development in Poland, grant: PBZ-MNiSW-2/3/2006. The authors thank also Professor W. Marczewski for kind sharing of some of the sequence-specific markers (ESM 1) used in this study and Dr. H. Bolibok-Brągoszewska for help in mapping.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by C. Gebhardt.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Śliwka, J., Jakuczun, H., Chmielarz, M. et al. A resistance gene against potato late blight originating from Solanum × michoacanum maps to potato chromosome VII. Theor Appl Genet 124, 397–406 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-011-1715-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-011-1715-4