Abstract

Objectives

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Easy-to-perform and reliable parameters are needed to predict the presence and severity of CAD and to implement efficient diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. We aimed to examine whether the Framingham risk scoring system can be used for this purpose.

Methods

A total of 222 patients (96 women, 126 men; mean age, 59.1 ± 11.9 years) who underwent coronary angiography were enrolled in the study. Presence of > %50 stenosis in a coronary artery was assessed as critical CAD. The Framingham risk score (FRS) was calculated for each patient. CAD severity was assessed by the Gensini score. The relationship between the FRS and the Gensini score was analyzed by correlation and regression analyses.

Results

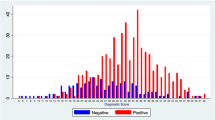

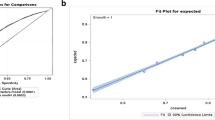

The mean Gensini score was 18.9 ± 25.8, the median Gensini score was 7.5 (0–172), the mean FRS was 7.7 ± 4.2, and the median FRS was 7 (0–21). Correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship between FRS and Gensini score (r = 0.432, p < 0.0001). This relationship was confirmed by linear regression analysis (β = 0.341, p < 0.0001). A cut-off level of 7.5 for FRS predicted severe CAD with a sensitivity of 68 % and a specificity of 73.6 % (ROC area under curve: 0.776, 95 % CI: 0.706–0.845, PPV: 78.1 %, NPV: 62.3 %, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Our work suggests that the FRS system is a simple and feasible method that can be used for prediction of CAD severity. As the sample size was small in our study, further large-scale studies are needed on this subject to draw solid conclusions.

Zusammenfassung

Ziele

Die koronare Herzkrankheit (KHK) ist weltweit eine der Hauptursachen für Morbidität und Mortalität. Leicht zu erhebende und verlässliche Parameter sind erforderlich, um das Vorliegen und den Schweregrad einer KHK vorherzusagen und wirksame Diagnostik- und Therapiemodalitäten einzusetzen. Ziel war zu untersuchen, ob das System des Framingham-Risikoscores (FRS) dazu verwendet werden kann.

Methoden

In die Studie aufgenommen wurden insgesamt 222 Patienten (96 w, 126 m, Durchschnittsalter: 59,1 ± 11,9 Jahre), bei denen eine Koronarangiographie erfolgte. Das Vorliegen einer Stenose von >50 % wurde als kritische KHK beurteilt. Der FRS wurde für jeden Patienten berechnet. Der Schweregrad der KHK wurde anhand des Gensini-Scores festgelegt. Der Zusammenhang zwischen FRS und dem Gensini-Scroe wurde durch Korrelations- und Regressionsanalysen ermittelt.

Ergebnisse

Der durchschnittliche Gensini-Score betrug 18,9 ± 25,8, der Median des Gensini-Scores 7,5 (0–172); der durchschnittliche FRS lag bei 7,7 ± 4,2 und der Median des FRS bei 7 (0–21). Die Korrelationsanalyse ergab einen signifikanten Zusammenhang zwischen FRS und Gensini-Score (r = 0,432; p < 0,0001). Dieser Zusammenhang wurde mittels linearer Regressionsanalyse bestätigt (β = 0,341; p < 0,0001). Ein Grenzwert von 7,5 für den FRS sagte eine schwere KHK mit einer Sensitivität von 68 % und einer Spezifität von 73,6 % voraus (ROC, Fläche unter der Kurve: 0,776; 95 %-KI: 0,706–0,845; PPV: 78,1 %; NPV: 62,3 %; p < 0,0001).

Schlussfolgerung

Die vorliegende Studie ergibt Hinweise darauf, dass das FRS-System eine einfache und praktikable Methode ist, die zur Vorhersage des Schweregrads einer KHK verwendet werden kann. Da die Stichprobengröße der Studie klein war, sind zukünftige Studien in größerem Umfang zu diesem Thema erforderlich, um beständige Schlussfolgerungen daraus zu ziehen.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Murray CJ, Lopez AD (1997) Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349:1269–1276

Murray CJ, Lopez AD (1997) Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349:1436–1442

Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D et al (2006) Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: the task force on the management of stable angina pectoris of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J 27:1341–1381

Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K et al (2007) European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary: fourth joint task force of the European society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (Constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 28:2375–2414

Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D et al (1998) Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 97:1837–1847

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS (1972) Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 18:499–502

Judkins MP (1967) Selective coronary arteriography: I: a percutaneous transfemoral technique. Radiology 89:815–824

Gensini GG (1983) A more meaningful scoring system for determining the severity of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 51:606

Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH (2004) The distribution of 10-Year risk for coronary heart disease among US adults: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Am Coll Cardiol 43:1791–1796

Eberly LE, Neaton JD, Thomas AJ, Yu D (2004) Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Multiple-stage screening and mortality in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Clin Trials 1:148–161

D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ et al (2008) General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham heart study. Circulation 117:743–753

British Cardiac Society, British Hypertension Society, Diabetes UK et al (2005) JBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart 91:v1–v52

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y et al (2007) Derivation and validation of QRISK, a new cardiovascular disease risk score for the United Kingdom: prospective open cohort study. BMJ 335:136

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Framingham Heart Study. Available from: http://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/

Gulec S (2009) Global risk and objectives in cardiovascular diseases. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 37(Suppl 2):1–10 (Article in Turkish)

D’Agostino RB Sr, Grundy S, Sullivan LM et al (2001) Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA 286:180–187

Menotti A, Puddu PE, Lanti M (2000) Comparison of the Framingham risk function-based coronary chart with risk function from an Italian population study. Eur Heart J 21:365–370

Zhang X, Jiang H, Lai J (1998) Relationship between the risk factors of coronary artery disease and the severity of coronary artery lesions. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 78:49–51 (Article in Chinese)

Birgelen C von, Hartmann M, Mintz GS et al (2004) Relationship between cardiovascular risk as predicted by established risk scores versus plaque progression as measured by serial intravascular ultrasound in left main coronary arteries. Circulation 110:1579–1585

Kim SW, Mintz GS, Escolar E et al (2006) The impact of cardiovascular risk factors on subclinical left main coronary artery disease: an intravascular ultrasound study. Am Heart J 152:693.e7–693.e12

Versteylen MO, Joosen IA, Shaw LJ et al (2011) Comparison of Framingham, PROCAM, SCORE, and Diamond Forrester to predict coronary atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. J Nucl Cardiol 18:904–911

Chung CP, Oeser A, Avalos I et al (2006) Utility of the Framingham risk score to predict the presence of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 8:R186

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sayin, M., Cetiner, M., Karabag, T. et al. Framingham risk score and severity of coronary artery disease. Herz 39, 638–643 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-013-3881-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-013-3881-4