Abstract

Objectives

Self-rated health can be influenced by several characteristics of the social environment. The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between self-rated health and self-assessed social class in Slovenian adult population.

Methods

The study was based on the Countrywide Integrated Non-communicable Diseases Intervention Health Monitor database. During 2004, 8,741/15,297 (57.1%) participants aged 25–64 years returned posted self-administered questionnaire. Logistic regression was used to determine unadjusted and adjusted estimates of association between poor self-rated health and self-assessed social class.

Results

Poor self-rated health was reported by 9.6% of participants with a decrease from lower to upper-middle/upper self-assessed social class (35.9 vs. 3.7%). Logistic regression showed significant association between self-rated health and all self-assessed social classes. In an adjusted model, poor self-rated health remained associated with self-assessed social class (odds ratio for lower vs. upper-middle/upper self-assessed social class 4.23, 95% confidence interval 2.46–7.25; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Our study confirmed differences in the prevalence of poor self-rated health across self-assessed social classes. Participants from lower self-assessed social class reported poor self-rated health most often and should comprise the focus of multisectoral interventions.

Zusammenfassung

Fragestellung

Der selbst-beschriebene Gesundheitszustand kann durch verschiedenartige soziale Faktoren beeinflusst werden. Das Ziel dieser Studie war es, den Zusammenhang zwischen selbst-beschriebenem Gesundheitszustand und selbst-definierter sozialer Klasse in einer Population slowenischer Erwachsener zu beschreiben.

Methoden

Die Studie verwendete die Countrywide Integrated Non-communicable Diseases Intervention Health Monitor Datenbank. Im Jahr 2004 schickten 8741/15297 (57.1%) Teilnehmern im Alter von 25–64 Jahren einen per Post versendeten Fragebogen zurück. Es wurden nichtadjustierte und adjustierte sowie logistische Regressionsmodelle für die Analyse des Zusammenhangs von schlechtem selbst-beschriebenem Gesundheitszustand und selbst-definierter sozialer Klasse verwendet.

Ergebnisse

Ein schlechter selbst-beschriebener Gesundheitszustand wurde von 9.6% der Teilnehmer berichtet, wobei sich ein Abfall von 35.9% bei niedrigerer bis 3.7% bei mittlerer/höherer selbst-definierter sozialer Klasse zeigte. In logistischen Regressionsmodellen waren selbst-beschriebene Gesundheit und alle selbst-definierten sozialen Klassen miteinander assoziiert. Ein adjustiertes Model zeigte, dass schlechterer selbst-bechriebener Gesundheitszustand mit der selbst-definierten sozialen Klasse assoziiert war (OR für niedrigere vs. mittlere/höhere selbst-definierten soziale Klasse 4.23, 95% CI 2.46–7.25; P < 0.001).

Schlussfolgerungen

Unsere Studie bestätigt das Vorhandensein von deutlichen Unterschieden hinsichtlich der Prävalenz von schlechtem selbst-beschriebenem Gesundheitszustand innerhalb verschiedener selbst-definierter sozialer Klassen. Teilnehmer aus der niedrigeren selbst-definierten sozialen Klasse hatten die größte Prävalenz des schlechteren selbst-beschriebenen Gesundheitszustandes und sollten in den Mittelpunkt multisektorischer Interventionsprogramme gerückt werden.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR (2000) Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol 19:586–592

Ahs A, Westerling R (2006) Self-rated health in relation to employment status during periods of high and of low levels of unemployment. Eur J Public Health 16:295–305

Altman DG (1993) Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman & Hall, London

Bauer GF, Huber CA, Jenny GJ, Mueller F, Haemmig O (2009) Socioeconomic status, working conditions and self-rated health in Switzerland: explaining the gradient in men and women. Int J Public Health 54:23–30

Blank N, Diderichsen F (1996) The prediction of different experiences of long-term illness: a longitudinal approach in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 50:156–161

Bobak M, Pikhart H, Rose R, Hertzman C, Marmot M (2000) Socioeconomic factors, material inequalities, and perceived control in self-rated health: cross-sectional data from seven post-communist countries. Soc Sci Med 51:1343–1350

Borrell C, Muntaner C, Benach J, Artazcoz L (2004) Social class and self-reported health status among men and women: what is role of work organization, household material standards and household labour? Soc Sci Med 58:1869–1887

Cox B, van Oyen H, Cambois E, Jagger C, le Roy S, Robine JM, Romieu I (2009) The reliability of the Minimum European Health Module. Int J Public Health 54:55–60

Darlington RB (1990) Regression and linear models. McGraw-Hill, New York

Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E, Marmot M (2008) Socioeconomic status and health: the role of subjective social status. Soc Sci Med 67:330–340

Franzini L, Fernandez-Esquer ME (2006) The association of subjective social status and health in low-income Mexican-origin individuals in Texas. Soc Sci Med 63:788–804

Gilmore ABC, McKee M, Rose R (2002) Determinants of and inequalities in self-perceived health in Ukraine. Soc Sci Med 55:2177–2188

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (1989) Applied logistic regression. Wiley, New York

Hu P, Adler NE, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Seeman TE (2005) Relationship between subjective social status and measures of health in older Taiwanese persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:483–488

Idler EL, Benyamini Y (1997) Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 38:21–37

Jylhä M (2009) What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med 69:307–316

Knesebeck O, Lueschen G, Cockerham WC, Siegrist J (2003) Socioeconomic status and health among the aged in the United States and Germany: a comparative cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med 57:1643–1652

Lang T, Delpierre C (2009) How are you? what do you mean? Eur J Public Health 19:353

Leinsalu M (2002) Social variation in self-rated health in Estonia: a cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med 55:847–861

Lundberg O, Manderbacka K (1996) Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scand J Soc Med 24:218–224

Lynch J, Kaplan G (2000) Socioeconomic position. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I (eds) Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 13–35

Lynch J, Davey Smith G, Hillemeier M, Shaw M, Raghunathan T, Kaplan G (2001) Income inequality, the psychosocial environment, and health: comparisons of wealthy nations. Lancet 358:194–200

Macleod J, Smith GD, Metcalfe C, Hart C (2005) Is subjective social status a more important determinant of health than objective social status? Evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish men. Soc Sci Med 61:916–929

Martikainen P, Lahelma E, Marmot M, Sekine M, Nishi N, Kagamimori S (2004) A comparison of socio-economic differences in physical functioning and perceived health among male and female employees in Britain, Finland, and Japan. Soc Sci Med 59:1287–1295

McCullough ME, Laurenceau JP (2004) Gender and the natural history of self-rated health: a 59-year longitudinal study. Health Psychol 23:651–655

McFadden E, Luben R, Bingham S, Wareham N, Kinmonth AL, Khaw KT (2008) Social inequalities in self-rated health by age: cross-sectional study of 22457 middle-aged men and women. BMC Public Health 8:230

Molarius A, Berglund K, Eriksson C, Lambe M, Nordström E, Eriksson HG, Feldman I (2007) Socioeconomic conditions, lifestyle factors, and self-rated health among men and women in Sweden. Eur J Public Health 17:125–133

Nicholson A, Bobak M, Murphy M, Rose R, Marmot MG (2005) Socio-economic influences on self-rated health in Russian men and women—a life course approach. Soc Sci Med 61:2345–2354

O’Relley EZ (2006) Privatization and some economic and social consequences: higher incomes, greater inequalities. Soc Sci J 43:497–502

Operario D, Adler NE, Williams DR (2004) Subjective social status: reliability and predictive utility for global health. Psychol Health 19:237–246

Pikhart H, Bobak M, Rose R, Marmot M (2003) Household item ownership and self-rated health: material and psychosocial explanations. BMC Public Health 3:38

Pikhart H, Bobak M, Siegrist J, Pajak A, Rywik S, Kyshegyi J, Gostautas A, Skodova Z, Marmot M (2001) Psychosocial work characteristics and self-rated health in four post-communist countries. J Epidemiol Community Health 55:624–630

Power C, Matthew S, Manor O (1996) Inequalities in self-rated health in the 1958 birth control: lifetime social circumstances or social morbidity? BMJ 313:449–453

Prättälä R, Helasoja V, Laaksonen M, Laatikainen T, Nikander P, Puska P (2001) CINDI Health Monitor. Proposal for practical guidelines, Publications of the National Public Health Institute, Helsinki

Roos E, Lahelma E, Saastamoinen P, Elstad JI (2005) The association of employment status and family status with health among women and men in four Nordic countries. Scand J Public Health 33:250–260

Rowan K (1994) Global questions and scores. In: Jenkinson C (ed) Measuring health and medical outcomes. Oxford University Press, London, pp 54–76

Rugulies R, Aust B, Burr H, Bueltmann U (2008) Job insecurity, chances on the labour market and decline in self-rated health in a representative sample of the Danish workforce. J Epidemiol Community Health 62:245–250

Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG (2003) Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Soc Sci Med 56:1321–1333

Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE (2005) Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med 67:855–861

Singh-Manoux A, Martikainen P, Ferrie J, Zins M, Marmot MG, Goldberg M (2006) What does self-rated health measure? Results from the British Whitehall II and French Gazel cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health 60:364–372

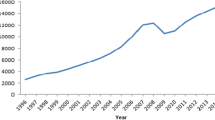

State Portal of the Republic of Slovenia (2009) Registered unemployment rate. http://e-uprava.gov.si/ispo/brezposelnost/zacetna.ispo. Accessed March 11 2009

Sverke M, Hellgren J, Naswall K (2002) No security: a meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J Occup Health Psychol 7:242–264

Vågerö D, Kislitsyna O, Ferlander S, Migranova L, Carlson P, Rimachevskaya N (2008) Moscow Health Survey 2004—social surveying under difficult circumstances. Int J Public Health 53:171–179

World Health Organization (1996) Protocol and guidelines: Countrywide Integrated Non-communicable Diseases Intervention (CINDI) Program. (Revision of 1994). World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen

Zaletel-Kragelj L (2004) Methods and participants. In: Zaletel-Kragelj L, Fras Z, Maučec-Zakotnik J (eds) Risky behaviour related to health and selected health conditions in adult population of Slovenia: results of Slovenia CINDI Health Monitor Survey 2001. CINDI Slovenia, Ljubljana, pp 9–38

Zaletel-Kragelj L, Erzen I, Fras Z (2004) Interregional differences in health in Slovenia. Estimated prevalence of selected cardiovascular and related diseases. Croat Med J 45:637–643

Acknowledgments

The study is a part of a joint project of Chair of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana and CINDI Slovenia. It was supported financially by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport and by the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Slovenia (Applied Research Project L3-3128-0381).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farkas, J., Pahor, M. & Zaletel-Kragelj, L. Self-rated health in different social classes of Slovenian adult population: nationwide cross-sectional study. Int J Public Health 56, 45–54 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0103-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0103-1