Abstract

Background. Lifestyle factors (eg, smoking, diet) and compliance with screening recommendations play a role in cancer risk, and emerging technologies (eg, new vaccines, genetic testing) hold promise for improved risk management.Methods. However, optimal outcomes from cancer control efforts require better preparation of health professionals in risk assessment, risk communication, and implementing health behavioral change strategies that are vitally important to cancer control.Results and Conclusion. Although physician assistants (PAs) are substantively engaged in cancer-related service delivery in primary care settings, few models exist to facilitate integration of cancer control learning experiences into the curricula used in intense, fast-paced, 24- to 30-month PA training programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson RN, Smith BL. Deaths: leading causes for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. May 7, 2005;53:1–89.

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2003. [November 2005 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER Web site, 2006]. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2003/.Accessed June 8, 2006.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2006. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006.

Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing and Controlling Cancer: The Nation’s Second Leading cause of Death—2004. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2005. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2005.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Comprehensive Cancer Control: Collaborating to Conquer Cancer. Atlanta, GA: Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004/2005.

US Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 2001 Incidence and Mortality. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2004.

Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, Etzioni R. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2004;40(suppl 8): IV-104–IV-117.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2000.

Helfand M, Mahon SM, Eden KB, Frame PS, Orleans CT. Screening for skin cancer. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(suppl 3):47–58.

Brose MS, Rebbeck TR, Calzone KA, Stopfer JE, Nathanson KL, Weber BL. Cancer risk estimates for BRCA1 mutation carriers identified in a risk evaluation program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1365–1372.

Humphrey LL, Helfand M, Chan BK, Woolf SH. Breast cancer screening: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(5 part 1):347–360.

Harris R, Lohr KN. Screening for prostate cancer: an update of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:917–929.

Berg A. Screening for Cervical Cancer: Recommendations and Rationale. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2003:03-515A.

US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS affirms value of mammography for detecting breast cancer. February 21, 2002. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2002pres/20020221.html. Accessed September 21, 2004.

Byers T, Mouchawar J, Marks J, et al. The American Cancer Society challenge goals: how far can cancer rates decline in the US by the year 2015? Cancer. 1999;86:715–727.

National Cancer Institute: Cancer control objectives for the nation: 1985–2000. NCI Monographs, NCI Publication #86-2880, no. 2, 1986.

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. Atlanta, GA: Office on Smoking and Health, Centers for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control; 1990. CDC publication 90-8416.

Greenwald P, Kramer B, Weed D. Cancer Prevention and Control. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1995.

Willet W. Diet and Nutrition. In Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni J Jr, eds. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996:438–461.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996.

Hanna E, Bachmann G. HPV vaccination with Gardasil: a break-through in women’s health. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6:1223–1227.

Easton DF, Bishop DT, Ford D, Crockford GP, and the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Genetic linkage analysis in familial breast and ovarian cancer: results from 214 families. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:678–701.

Ford D, Easton DF, Bishop DT, Narod SA, Goldgar DE and the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Risks of cancer in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Lancet. 1994;343:692–695.

Ford D, Easton DF. The genetics of breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:805–812.

Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT, and the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:265–271.

Thompson D, Easton DF. Cancer Incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1358–1365.

Nelson HD, Huffman LH, Fu R, Harris EL. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:362–379.

Weir HK, Thun MJ, Hankey BF, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1965–2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1276–1299.

Institute of Medicine. Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2003.

Abed J, Reilley B, Butler MO, Kean T, Wong F, Hohman K. Comprehensive cancer control initiative of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: an example of participatory innovation diffusion. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2000;6:79–92.

Cawley JF, Andrews MD, Barnhill GC, Webb L, Hill IK. What makes the day?: an analysis of the content of physician assistants’ practice. JAAPA. May 2001;14:41–44, 47–50, 55–46.

Hooker RS. A cost analysis of physician assistants in primary care. JAAPA. November 2002;15:39–42, 45, 48.

American Academy of Physician Assistants. Number of Visits to Physician Assistants for Select Disorders in 2006. Information Update October. Available at: http://www.aapa.org/research/06disorders.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2007.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services: An assessment of the effectiveness of 169 interventions. Report of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1989.

Albright CL, Cohen S, Gibbons L, et al. Incorporating physical activity advice into primary care: physician-delivered advice within the activity counseling trial. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:225–234.

Becker MH, Janz NK. Practicing health promotion: the doctor’s dilemma. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:419–422.

Emmons KM, Stoddard AM, Gutheil C, Suarez EG, Lobb R, Fletcher R. Cancer prevention for working class, multi-ethnic populations through health centers: the healthy directions study. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:727–737.

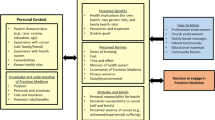

Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, et al. Model for incorporating social context in health behavior interventions: applications for cancer prevention for working-class, multiethnic populations. Prev Med. 2003;37:188–197.

Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S3-S32.

American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2006 AAPA Physician Assistant Census Report. October 23, 2006. Available at: http:// www.aapa.org/research/06census-content.html#sec01. Accessed January 30, 2007.

Hooker RS, Berlin LE. Trends in the supply of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):174–181.

Amara R, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and The Institute for the Future, Health and Health Care 2010: The Forecast, the Challenge. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2000.

Institute of Medicine, ed. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2003. Greiner A, Knebel E, eds.

Layne-Bass R. Health education, looking beyond the patient encounter. Perspective Physician Assistant Education. 1999;10:216–218.

Simon A, Link M, Miko A. Fifteenth Annual Report on Physician Assistant Educational Programs in the United States, 1998–99. Alexandria, VA: The Association of Physician Assistant Programs; 1999.

Accreditation Review Committee on Education for the Physician Assistant. Accreditation Standards for Physician Assistant Education. Marshfield, WI: Accreditation Review Committee on Education for the Physician Assistant; 2001.

Fasser CE, Mullen PD, Holcomb JD. Health beliefs and behaviors of physician assistants in Texas: implications for practice and education. Am J Prev Med. 1988;4:208–215.

Aparasu RR, Hegge M. Autonomous ambulatory care by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in office-based settings. J Allied Health. 2001;30:153–159.

Shilling V, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Factors affecting patient and clinician satisfaction with the clinical consultation: can communication skills training for clinicians improve satisfaction? Psychooncology. 2003;12:599–611.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. General competencies (full version). February 1999. Available at: http:// www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compFull.asp. Accessed July 18, 2006.

American Board of Medical Specialties. Approved Initiatives for Maintenance of Certification for the ABMS Member Boards: Description of the Competent Physician. September 23, 1999. Available at: http://www.abms.org/Downloads/Publications/3-Approved%20 Initiatives%20for%20MOC.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2006.

Chakravarthy MV, Joyner MJ, Booth FW. An obligation for primary care physicians to prescribe physical activity to sedentary patients to reduce the risk of chronic health conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:165–173.

Westmaas JL, Brandon TH. Reducing risk in smokers. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:284–288.

Emmons KM, McBride CM, Puleo E, et al. Project PREVENT: a randomized trial to reduce multiple behavioral risk factors for colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1453–1459.

Andrykowski MA, Beacham AO, Schmidt JE, Harper FW. Application of the theory of planned behavior to understand intentions to engage in physical and psychosocial health behaviors after cancer diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2006;15:759–771.

Zhang Z, Haile R, Peters R, et al. Cancer Prevention Competencies Summary. 2006. Available at: http://apps.medsch.ucla.edu/cancer/ competencies.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2006.

The University of Texas Medical Branch Educational Cancer Center. Cancer Teaching and Curriculum Enhancement in Undergraduate Medicine. July 12. Available at: http://www.catchum.utmb.edu/ index.htm. Accessed September 21, 2004.

Oncology Core Competencies for Medical Students. 2004. Available at: http://www.catchum.utmb.edu/resources/CATCHUM%20Core%20 Comptencies4_06.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2006.

Fasser C, Thomson W, Hefley D, Smith Q. Early detection of oral cancer. Physician Assistant/Health Practitioner. August 1982;6:49–53.

Newland J, Fasser C, Smith Q, Thomson W. Clinical diagnosis of localized intraoral swellings. Physician Assistant. 1983;7:88–99.

Wolf J, Fasser C, Smith Q, Thomson W. Common skin cancers. Physician Assistant. May 1983;7:40–52.

Newland J, Lynch D, Fasser C, Smith Q. Denture-related oral lesions in the elderly. Physician Assistant. December 1983;7:37–42.

Friedman LC, Neff NE, Webb JA, Latham CK. Age-related differences in mammography use and in breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. J Cancer Educ. 1998;13:26–30.

Basch CE, Eveland JD, Portnoy B. Diffusion systems for education and learning about health. Fam Community Health. August 1986;9:1–26.

Rogers E. Diffusion of Innovation. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1995.

Novick LF. Introducing a case-based teaching intervention in preventive medicine education. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(suppl 4):83–84.

McCurdy SA. Preventive medicine teaching cases in the preclinical undergraduate medical curriculum. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(suppl 4): 108–110.

Cleary LM. Population-based prevention: a core competency in medical education. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(suppl 4):161–163.

Morrow CB, Epling JW, Teran S, Sutphen SM, Novick LF. Future applications of case-based teaching in population-based prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(suppl 4):166–169.

Epling JW, Morrow CB, Sutphen SM, Novick LF. Case-based teaching in preventive medicine: rationale, development, and implementation. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(suppl 4):85–89.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–395.

DiClemente C, Prochaska J. Processes and stages of change: Coping and competence in smoking behavior change. In: Shiffman S, Wills T, eds. Coping and Substance Abuse. New York, NY: Academic Press: 1985:319–342.

Prochaska JO. Assessing how people change. Cancer. 1991;67(suppl 3): 805–807.

DiClemente CC, Scott CW. Stages of change: interactions with treatment compliance and involvement. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;165:131–156.

Poirier MK, Clark MM, Cerhan JH, Pruthi S, Geda YE, Dale LC. Teaching motivational interviewing to first-year medical students to improve counseling skills in health behavior change. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:327–331.

Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings. Opportunities and limitations. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20: 68–74.

Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Frosch DL, Kaplan RM. Shared decision making in clinical medicine: past research and future directions. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:285–294.

Ragan P. Evidence-based practice: communicating risk. Perspective on Physician Assistant Education. 2003;14:256–258.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (Grant 1R25CA109743-01A2)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, Q.W., Fasser, C.E., Spence, L.R. et al. Educating physician assistants as agents in cancer control: Issues and opportunities. J Canc Educ 22, 227 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03174121

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03174121