Summary

-

1.

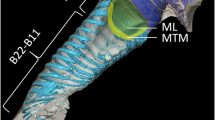

Oilbirds (Steatornis caripensis; Steatornithidae) have a bilaterally asymmetrical bronchial syrinx (Fig. 2) with which they produce echolocating clicks and a variety of social vocalizations. The sonar clicks typically have a duration of about 40 to 50 ms and can be classified as continuous, double or single. Agonistic squawks typically have a duration of about 0.5 s and contain multiple harmonic components (Figs. 5, 6).

-

2.

Both sonar clicks and agonistic squawks are initiated by contraction of the sternotrachealis muscles (Figs. 7 and 16) which stretch the trachea, reducing the tension across the syrinx and causing the cartilaginous bronchial semi-rings supporting the cranial and caudal edges of the external tympaniform membranes (ETM) to hinge inward, folding the ETM into the syringeal lumen (Fig. 17). Bernoulli forces created by expiratory air flowing through the restricted syringeal aperture presumably initiate vibration of the internal and/or external tympaniform membranes.

-

3.

Social vocalizations such as the agonistic squawk, continue until the sternotrachealis muscles relax (Fig. 10), allowing the cranial portion of the bronchus to move anteriad and abducting the ETM.

-

4.

Sonar clicks are terminated by rapid contraction of a previously undescribed intrinsic syringeal muscle, the broncholateralis, which inserts on the semi-ring supporting the anterior edge of the ETM and causes it to rotate about its articulation with the next anterior bronchial cartilage in such a way that it abducts the ETM (Figs. 8, 16, 17). Musculus broncholateralis contracts only during sonar clicks, appears to have a high proportion of twitch-type fibers, and is specialized for the rapid abduction of the ETM to produce short duration, click-like vocalizations.

-

5.

Tracheal airflow and sternal air sac pressure reflect the changes in the syringeal aperture. Tracheal airflow at first increases as expiratory effort increases subsyringeal pressure. The initial high rate of airflow drops at the onset of phonation due to the increased syringeal resistance. In the case of a double click, airflow momentarily ceases during the intraclick interval when the ETM temporarily closes the syrinx. Air sac pressure rises to its maximum level at this time. Expiratory airflow rapidly increases as the ETM is abducted from either its closed or phonatory position to its open, resting position. Each sonar click requires about 1 cm3 of air; a typical agonistic squawk may use about 27 cm3 of air (Figs. 11, 12, 13; Tables 3, 4).

-

6.

Each sonar click is often accompanied by a complete respiratory cycle or ‘mini-breath’ (Fig. 11). Pulmonary ventilation can be controlled independently from the clicking rate by varying the tidal volume of the mini-breaths, which may be as small as the tracheal and bronchial dead space. Mini-breaths permit oilbirds to produce click trains having a long train duration uninterrupted by a long inspiration.

-

7.

A dual flow probe was used to simultaneously measure the rate of airflow through each semi-syrinx during vocalization. The rate of airflow through the right semi-syrinx was 40 to 60% greater than that through the left. Both syringes functioned together except during the middle portion of some continuous type sonar clicks when sound was sometimes generated only by one semi-syrinx, the other being closed (Figs. 14, 15; Tables 5, 6).

-

8.

The fluid subsyringeal power reaches approximately 100 and 150 mW in the left and right semi-syrinx, respectively, during the second member of a double sonar click (Table 6). Total syringeal power during agonistic squawks reaches at least 60 mW and syringeal resistance during these vocalizations is as high as 1500 cm H20/LPS (Table 7).

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- EMG :

-

electromyogram

- ETM :

-

external tympaniform membrane(s)

- ITM :

-

internal tympaniform membrane

- LPS :

-

liters/second

References

Beddard FE (1885) On structural characters and classification of the cuckoos. Proc Zool Soc (Lond) 1885:168–187

Beddard FE (1886) On the syrinx and other points in the anatomy of the Caprimulgidae. Proc Zool Soc (Lond) 1886:147–153

Beddard FE (1902) On the syrinx and other points in the structure ofHierococcyx and some allied genera of cuckoos. Ibis 2:599–608

Berger AJ (1960) Some anatomical characters of the Cuculidae and the Musophagidae. Wilson Bull 72:60–104

Brackenbury JH (1972) Lung-air-sac anatomy and respiratory pressures in the bird. J Exp Biol 57:543–550

Brackenbury JH (1977) Physiological energetics of cock-crow. Nature 270:433–435

Brackenbury JH (1978) Respiratory mechanics of sound production in chickens and geese. J Exp Biol 72:229–250

Brackenbury JH (1980) Control of sound production in the syrinx of the fowl,Gallus gallus. J Exp Biol 85:239–251

Brackenbury JH (1982) The structural basis of voice production and its relationship to sound characteristics. In: Kroodsma D, Miller E (eds) Acoustic communication in birds, vol 1. Academic Press, New York, pp 53–73

Calder WA (1970) Respiration during song in the canary,Serinus canaria. Comp Biochem Physiol 32:251–258

Chamberlain DR, Cross WB, Cornwell GW, Mosby HS (1968) Syringeal anatomy in the common crow. Auk 89:244–252

Duncker H-R (1971) The lung air sac system of birds. A contribution to the functional anatomy of the respiratory apparatus. Erg Anat Entwicklungsgesch 45:1–171

Gadow H, Selenka E (1891) Aves. In: Bronn's Klassen und Ordnungen des Tierreichs, vol 6, Part IV, No 1, Leipzig

Garrod AH (1873) On some points in the anatomy ofSteatornis. Proc Zool Soc (Lond) 1873:457–472

Gaunt AS, Stein RC, Gaunt SLL (1973) Pressure and air flow during distress calls of the starling,Sturnis vulgaris (Aves: Passeriformes). J Exp Zool 183:241–262

Gaunt AS, Gaunt SLL, Hector DH (1976) Mechanics of the syrinx inGallus gallus. I. A comparison of pressure events in chickens to those in oscines. Condor 78:208–223

Gaunt AS, Gaunt SLL, Casey RM (1982) Syringeal mechanics reassessed: Evidence fromStreptopelia. Auk 99:474–494

Griffin DR (1953) Acoustic orientation in the oilbird,Steatornis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 39:884–893

Griffin DR, Thompson D (1982) Echolocation by cave swiftlets. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 10:119–123

Gross WB (1964) Voice production by the chicken. Poult Sci 43:1005–1008

Hess A (1965) The sarcoplasmic reticulum, the T-system and the motor terminals of slow and twitch muscle fibers in the Garter Snake. J Cell Biol 26:467–476

Konishi M, Knudsen E (1979) The oilbird: Hearing and echolocation. Science 204:425–427

Kulzer E (1956) Flughunde erzeugen Orientierungslaute durch Zungenschlag. Naturwissenschaften 43:117–118

Kulzer E (1960) Physiologische und morpholoigsche Untersuchungen über die Erzeugung der Orientierungslaute von Flughunden der GattungRousettus. Z Vergl Physiol 43:231–268

Miller AH (1934) The vocal apparatus of some North American Owls. Condor 36:204–213

Miskimen M (1951) Sound production in passerine birds. Auk 68:493–504

Müller J (1841) Über die Anatomie desSteatornis caripensis. Akademie der Wissenschaften Bericht, Berlin, pp 172–179

Müller J (1842) Anatomische Bemerkungen über den Quacharo (Steatornis caripensis). Arch Anat Physiol Wissenschaft Medicin (Müller's Arch), Berlin, pp 1–11

Page SG (1965) A comparison of the fine structures of frog slow and twitch muscle fibers. J Cell Biol 26:477–490

Pye JD (1980) Echolocation signals and echoes in air. In: Busnel R-G, Fish JF (eds) Animal sonar systems. Plenum, New York, pp 309–353

Roberts LH (1972) Correlation of respiration and ultrasound production in rodents and bats. J Zool 168:439–449

Schnitzler H-U (1968) Die Ultraschall-Ortungslaute der Hufeisen-Fledermäuse (Chiroptera-Rhinolophidae) in verschiedenen Orientierungssituationen. Z Vergl Physiol 57:376–408

Seller TJ (1979) Unilateral nervous control of the syrinx in Java Sparrows, (Padda oryzivora). J Comp Physiol 129:281–288

Smith DG (1977) The role of the sternotrachealis muscles in birdsong production. Auk 94:152–155

Snow DW (1961) The natural history of the oilbird,Steatornis caripensis, in Trinidad, WI. I. General behavior and breeding habits. Zoologica 46:27–48

Snow DW (1962) The natural history of the oilbird,Steatornis caripensis, in Trinidad, WI. II. Population, breeding ecology and food. Zoologica 47:199–221

Suthers RA, Fattu JM (1973) Mechanisms of sound production by echolocating bats. Am Zool 13:2115–1226

Suthers RA, Hector DH (1982) Mechanism for the production of echolocating clicks by the grey swiftlet,Collocalia spodiopygia. J Comp Physiol 148:457–470

Suthers RA, Thomas SP, Suthers BJ (1972) Respiration, wingbeat and pulse emission in an echolocating bat. J Exp Biol 56:37–48

Wunderlich L (1884) Beiträge zur vergleichenden Anatomie und Entwicklungsgeschichte des unteren Kehlkopfes der Vögel. Leopoldinisch-Carolinische Deutsch Akad Naturforscher. Nova Acta 48:1–80

Youngren OM, Peek FW, Phillips RE (1974) Repetitive vocalizations evoked by local electrical stimulation of avian brains: III. Evoked activity in the tracheal muscles of the chicken (Gallus gallus). Brain Behav Evol 9:393–421

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Suthers, R.A., Hector, D.H. The physiology of vocalization by the echolocating oilbird,Steatornis caripensis . J. Comp. Physiol. 156, 243–266 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00610867

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00610867