Summary

-

1.

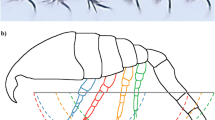

The cercaria of Diplostomum spathaceum (Rudolphi, 1819) shows 2 phases in its swimming behaviour: A period of sinking lasting between 2 and 120 sec (passive phase) alternates with a rapid active swimming motion (active phase), usually in an upward direction, of between 1/10 and 3 sec, and in length usually between 2 and 8 mm, with a maximum of 16 mm. Both phases were quantitatively registered by measuring the duration of sinking, t (passive phase) and the length of the active swimming motion, s (active phase).

-

2.

The spontaneous activity of the cercaria is affected, above all, (1) by temperature (s and t decrease with a rise in temperature, Table 1) and (2) by the intensity of light (s increases and t decreases with increasing light intensity, Table 2). Accordingly the negative geotaxis increases with the increase in mounting velocity, caused by rising light intensity and decrease in temperature. Positive phototaxis was established although there is no evidence of shielding pigments in the ocelli.

-

3.

The reaction to stimulation by light depends, among other things, on whether the stimulation takes place in the active or in the passive phase, and whether the change of light intensity is positive or negative.

-

a)

Shadowing in the passive phase may release an active swimming motion which occurs in accordance with the “all-or-none” rule. It depends mainly on the duration of the stimulus (Table 4), the difference in light intensity (Table 11), and the speed of its change (Table 5). The release readiness is also related to the state of excitation of the mechanism, which is responsible for triggering spontaneous swimming motions, and differs in the parasite of the population according to the individual host. Shadowing, which does not in itself initiate a swimming motion, produces the following effects: t is prolonged (demonstrable only when the cercaria is in a state of low release readiness, Fig. 4), and s is shortened. In this case it seems that only the difference of light intensity has a bearing (and not the speed of change in light intensity).

-

b)

Shadowing in the active phase inhibits swimming motions. This inhibition occurs in accordance with the “all-or-none” rule and depends on the difference in light intensity and the duration of the stimulus (Table 13).

-

c)

Stimulation by increased light intensity in the passive phase delays the start of the swimming motion (Figs. 7, 8) and lengthens it (Table 15) according to the difference in light intensity of the stimulus (but apparently independent of the speed with which the intensity changes, Table 16).

-

d)

Stimulation by increased light intensity in the active phase lengthens the swimming motion according to the difference in the light intensity of the stimulus (Table 14) and often delays the start of the ensuing swimming motion.

-

a)

-

4.

Stimulation by turbulence and touch in the passive phase results in the release of swimming motions and prolongs the subsequent t. Applied in the active phase it lengthens s.

-

5.

Whereas s and t of consecutive spontaneous swimming motions are independent of one another in their dimensions (Table 3, Fig. 1), and since they can be oppositely affected by stimulation, two separate mechanisms are postulated for the regulation of the spontaneous activity: (1) a mechanism to determine the length of the active swimming motion s; and (2) a release mechanism which determines the start of the active swimming motion and thus the duration of the passive phase t. Since isolated tails show a spontaneous activity, at least a part of these mechanisms must be localized in the tail.

-

6.

The effect of optical stimulation on these mechanisms is presented in a preliminary functional model (Fig. 9).

Zusammenfassung

-

1.

Die Cercarie von Diplostomum spathaceum (Rudolphi 1819) zeigt 2 Phasen des Schwimmverhaltens: ein passives Absinken von 2–120 sec Dauer (Passiv-Phase) und einen schnellen, gewöhnlich nach oben gerichteten Schwimmstoß von 1/10–3 sec Dauer und einer Länge von 2–8, maximal 16 mm (Aktiv-Phase). Beide Phasen wurden quantitativ erfaßt durch Messen der Absinkdauer t (Passiv-Phase) und der Schwimmstoßlänge s (Aktiv-Phase).

-

2.

Die Spontanaktivität der Cercarie wird u.a. beeinflußt durch Temperatur (mit zunehmender Temperatur verkürzen sich s und t, Tabelle 1) und Lichtintensität (mit zunehmender Lichtintensität verlängert sich s und verkürzt sich t, Tabelle 2). Die positive Geotaxis wächst (durch Erhöhung der Aufstiegsgeschwindigkeit) danach bei zunehmender Lichtintensität und abnehmender Temperatur. Eine positive Phototaxis wurde nachgewiesen, obwohl den Ocellen auffallende Abschirmpigmente fehlen.

-

3.

Die Reaktion auf Beleuchtungsreize hängt u. a. davon ab, ob der Beiz in der Passiv-Phase oder in der Aktiv-Phase gegeben wird, und ob es sich um einen positiven oder negativen Lichtintensitätswechsel handelt:

-

a)

Ein Dunkelreiz, gegeben in der Passiv-Phase kann Schwimmstöße auslösen. Die Auslösung erfolgt nach der Alles-oder-Nnichts-Regel und hängt u. a. ab von Dauer und Helligkeitsunterschied des Reizes (Tabellen 4, 11) und von der Geschwindigkeit des Lichtintensitätswechsels (Tabelle 5). Die Auslösebereitschaft der Cercarie steht außerdem in Zusammenhang mit dem Erregungszustand des Mechanismus, der den Start spontaner Schwimmstöße bewirkt und ist bei Parasitenpopulationen der einzelnen Wirtsindividuen unterschiedlich ausgebildet. Wirkung auf durch den Reiz nicht ausgelöste Schwimmstöße: Verlängerung von t (nur bei geringer Auslösebereitschaft der Cercarien nachweisbar, Abb. 4) und Verkürzung von s, wobei offenbar nur der Helligkeitsunterschied des Reizes beeinflußt, nicht die Geschwindigkeit des Lichtintensitätswechsels.

-

b)

Ein Dunkelreiz in der Aktiv-Phase hemmt den Schwimmstoß. Die Hemmung erfolgt nach der Alles-oder-Nichts-Regel und hängt ab vom Helligkeitsunterschied und der Dauer des Reizes (Tabelle 13).

-

c)

Ein Belichtungsreiz in der Passiv-Phase verzögert den Start des Schwimmstoßes (Abb. 7, 8) und verlängert ihn (Tabelle 15) in Abhängigkeit vom Helligkeitsunterschied des Reizes (offenbar unabhängig von der Geschwindigkeit des Lichtintensitätswechsels, Tabelle 16).

-

d)

Ein Belichtungsreiz in der Aktiv-Phase verlängert den Schwimmstoß in Abhängigkeit vom Helligkeitsunterschied des Reizes (Tabelle 14) und verzögert oft die Auslösung des folgenden Schwimmstoßes.

-

4.

Auf Turbulenz- und Berührungsreize in der Passiv-Phase werden Schwimmstöße ausgelöst und das nachfolgende t verlängert. In der Aktiv-Phase gegeben, verlängern sie den Schwimmstoß.

-

5.

Da s und t aufeinanderfolgender spontaner Schwimmstöße in ihrer Größe voneinander unabhängig sind (Tabelle 3, Abb. 1) und von Reizen entgegengesetzt beeinflußt werden können, wurden für die Steuerung der Spantanaktivität 2 getrennte Mechanismen postuliert: 1. ein Schwimmstoß-beeinflussender Mechanismus, der die Länge des Schwimmstoßes s festlegt, 2. ein Auslösemechanismus, der den Start des Schwimmstoßes und damit die Dauer der Passiv-Phase bestimmt. Da isolierte Schwänze eine Spontanaktivität zeigen, müssen zumindest Teile dieser Mechanismen im Schwanz gelegen sein.

-

6.

Die Wirkung der optischen Reize auf diese Mechanismen wurde in einem vorläufigen Funktionsmodell dargestellt (Abb. 9).

Similar content being viewed by others

Literatur

Bevelander, G.: Response to light in the cercariae of Bucephalus elegans. Physiol. Zool. 6, 289–305 (1933).

Dönges, J.: Reizphysiologische Untersuchungen an der Cercarie von Posthodiplostomum cuticola (v. Nordmann, 1832) Dubois 1936, dem Erreger des Diplostomatiden-Melanoms der Fische. Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. München, 216–223 (1963).

—: Der Lebenszyklus von Posthodiplostomum cuticola (v. Nordmann, 1832) Dubois 1936 (Trematoda, Diplostomatidae). Z. Parasitenk. 24, 169–248 (1964).

Dubois, G.: Les cercaires de la région de Neuchâtel. Bull. Soc. neuchâtel. Sci. nat. 53, 1–177 (1929).

Erasmus, D. A.: Studies on the morphology, biology and development of a strigeid cercaria (Cercaria X Baylis, 1930). Parasitology 48, 312–336 (1958).

Folger, H. T., and L. E. Alexander: The response to mechanical shock by the cercariae of Bucephalus elegans. Physiol. Zool. 11, 82–88 (1938).

Miller, H. M.: Behavior studies on Tortugas larval trematodes, with notes on the morphology of two additional species. Year Books, Carneg. Inst. Wash. 25, 243–247 (1926).

—: Further studies on the behavior of larval trematodes from Dry Tortugas. Year Books, Carneg. Inst. Wash. 26, 224–226 (1927).

—: Variety of behavior of larval trematodes especially to changes of light-intensity. Anat. Rec. 41, 36–37 (1928).

—: Variety of behavior of larval trematodes. Science 68, 117–118 (1928).

—: Continuation of study on behavior and reactions of marine cercariae from Tortugas. Year Books, Carneg. Inst. Wash. 28, 292–294 (1929).

Miller, H. M., and E. E. Mahaffy: Reactions of Cercaria hamata to light and to mechanical stimuli. Biol. Bull. 59, 95–103 (1930).

—, and O. R. McCoy: An experimental study of the behavior of Cercaria floridensis in relation to its fish intermediate host. Year Books, Carneg. Inst. Wash. 28, 295–297 (1929).

—: An experimental study of the behavior of Cercaria floridensis in relation to its intermediate host. J. Parasit. 16, 185–197 (1930).

Ratanarat, C.: Untersuchungen über den Wanderweg augenbewohnender Diplostomatiden-Larven (Diplostomum spathaceum und Posthodiplostomum brevicaudatum) in Fischen. Naturw. Diss. Tübingen, 51 S. (1968).

Standen, O. D.: Experimental Schistosomiasis. I. The culture of the snail vectors Planorbis boissyi and Bulinus truncatus. Ann. trop. Med. Parasit. 43, 13–22 (1949).

Styczynska-Jurewicz, E.: On the geotaxis, invasivity and span of life of Opisthioglyphe ranae DUJ. cercariae. Bull. Acad. pol. Sci. Cl. II. Sér. Sci. biol. 9, 31–35 (1961).

Szidat, L.: Beiträge zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Holostomiden. II. Entwicklung der Cercaria C. Zool. Anz. (Lpz.) 61, 249–266 (1924).

Timmermann, W.: Zur Biologie von Cercaria C (Szidat) und Diplostomum volvens (v. Nordmann). 63 S. Diss. München (1936).

Wheeler, N. C.: A comparative study on the behavior of four species of pleurolophocercous cercariae. J. Parasit. 25, 343–353 (1939).

Wunder, W.: Wie erkennt und findet Cercaria intermedia, nov. spec., ihren Wirt? Zool. Anz. 57, 68–88 (1923).

Zdun, W.: Die Beaktionen der Cercarien auf Einflüsse der Umwelt. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie—Sklodowska 20, 22 Sectio C, 341–348 (1965).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Meinem verehrten Lehrer, Herrn Doz. Dr. J. Dönges, danke ich für die Anregung zu dieser Arbeit und für seine stetige freundliche Unterstützung.

Für kritische Durchsicht des Manuskriptes und wertvolle Ratschläge bin ich Herrn Prof. Dr. P. Huber sehr zu Dank verpflichtet.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haas, W. Reizphysiologische Untersuchungen an Cercarien von Diplostomum spathaceum . Z. vergl. Physiologie 64, 254–287 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00340546

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00340546