Abstract

Job demands-resources (JD-R) theory has emerged as one of the most influential conceptual frameworks for interpreting and explaining factors affecting employees’ wellbeing in the workplace. The present chapter provides a broad overview of JD-R theory, and discusses how the theory can be harnessed to further understand the factors influencing teachers’ wellbeing. The chapter also reviews prior research employing JD-R theory in teaching populations, and explores the job demands (e.g., workload, disciplinary issues, time pressure) and job resources (e.g. perceived autonomy support, opportunities for professional learning, and relationships with colleagues) that influence teacher engagement, burnout, and organisational outcomes. Theoretical extensions of the model, such as the inclusion of personal resources (e.g. adaptability, cognitive and behavioural coping, self-efficacy), are further considered to extend knowledge of how teacher wellbeing can be promoted at both an individual and broader organisational level. Finally, the chapter considers the practical implications of how JD-R theory can guide interventions, comprising whole-school efforts, as well as approaches that support individual teachers to maximise their wellbeing.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Since its introduction in 2001, Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory (Bakker and Demerouti 2017; Demerouti et al. 2001) has come to be one of the most popular and widely published frameworks for understanding employee health and performance. In more recent times, the framework has been shown to be useful in further understanding the occupational experiences of teachers, and in shedding light on the nature of attrition and retention in the teaching profession. The present chapter introduces JD-R theory, and reviews prior research employing the model in teaching populations, with a focus on teacher wellbeing. In addition, we propose that although JD-R theory is predominantly relevant to wellbeing, it also holds relevance for understanding resilience. Justification of this stance is presented. The chapter then demonstrates how the theory can be applied in teaching contexts to promote teacher wellbeing.

2 Operationalising Teacher Wellbeing and Resilience

Wellbeing is a broad and multi-dimensional concept. In the present article, we define wellbeing as teachers’ positive evaluations of and healthy functioning in their work environment (Collie et al. 2016). Accordingly, wellbeing encompasses a range of outcomes, such as job satisfaction (teachers’ affective responses to their work; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2011), and organisational commitment (teachers’ emotional attachment to their work; Meyer and Allen 1991). As noted above, our major focus in this chapter is on wellbeing as a desirable outcome among teachers. At the same time, we also highlight the role of resilience in helping teachers to overcome the day-to-day challenges that arise in teaching. This dual approach of harm reduction and wellness promotion is important because resilience is important for overcoming adversity, whereas wellbeing is important for helping individuals to further flourish (Collie and Perry 2019).

Resilience research originally stemmed from work examining how children and adolescents overcome major or chronic adversity (e.g., Masten 2007). Among teachers, work has evolved to focus on low levels of adversity common to teachers (e.g., competing deadlines) through research on, for example, ‘everyday resilience’ (Gu and Day 2014) and workplace buoyancy (Martin and Marsh 2008). For this chapter, we operationalise resilience as a process involving resource mobilisation by individuals and resource provision by the context that in concert help individuals to navigate adversity (Ungar 2008). Importantly, we focus on low-level adversity such as competing deadlines and high workload that are common to teachers, rather than major adversity (Martin and Marsh 2008).

3 The Job Demands-Resources Theory

Job Demands-Resources theory adopts a positive psychology approach (Bakker and Demerouti 2008) to explaining employees’ workplace experiences. The central premise of the theory is that the working conditions within all occupations can be broadly defined as either job demands or job resources (Demerouti et al. 2001). Job demands are the physical, social, organisational, or psychological aspects of work that require the investment of physical and/or psychological effort, and are associated with energy depletion and psychological and/or physiological costs (e.g., workload, disciplinary issues, time pressure; Demerouti et al. 2001). In contrast to job demands, job resources are those elements of work that enable employees to: achieve work goals; manage job demands, and the associated physical and psychological costs; and grow and develop in their position (e.g., perceived autonomy support, opportunities for professional learning, and relationships with colleagues).

In addition to job demands and job resources, more recent conceptualising in JD-R theory has acknowledged the role that personal resources play in shaping employees’ workplace experiences (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). Broadly defined as self-evaluations of one’s ability to control and impact upon their environment (Hobfoll et al. 2003), personal resources can directly predict or indirectly influence how job demands and job resources affect employee outcomes. For example, self-efficacy (a personal resource) may influence a teacher’s perception of the school climate (a job resource), which in turn may increase their feelings of commitment (an outcome; Collie et al. 2011). Alternatively, individuals working in a school with a positive school climate (a job resource) may be higher in self-efficacy (a personal resource), which may positively influence their job performance (an outcome; Klassen and Tze 2014). In studies of teachers, personal resources have been found to be important predictors of a range of outcomes. For instance, Lorente Prieto et al. (2008) found self-efficacy to be a predictor of higher engagement and lower burnout among Spanish teachers. Comparatively, Xanthopoulou et al. (2007) found that personal resources influence the way in which job resources relate to engagement among Finnish teachers. Importantly, because personal resources such as self-efficacy and adaptability are capacities that individuals may be able to develop or change, they provide a useful base from which interventions targeting teachers’ wellbeing may be developed.

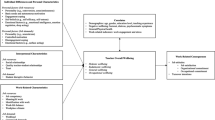

As can be seen in Fig. 14.1, the JD-R theory suggests that job demands and job/personal resources evince two independent psychological processes: the health impairment process in which job demands uniquely predict burnout, and the motivational process in which job/personal resources are inherently motivational and lead to higher work engagement and wellbeing (Bakker and Demerouti 2017). It is through these two processes that links with salient personal and occupational outcomes, such as organisational commitment, job performance, and turnover intentions can be understood (Collie et al. 2018; Esteves and Lopes 2017; Taris 2006).

Adapted from Bakker and Demerouti (2017)

The job demands-resources model, annotated to include a range of the key demands, resources, and outcomes previously examined in teachers.

In addition to the main associations between job demands and burnout (health impairment process) and those between job/personal resources and engagement (motivational process), JD-R theory also recognises two more nuanced processes: the ‘buffering’ and the ‘boosting’ effects. The ‘buffering’ effect refers to instances in which certain job resources buffer or lessen the effect of demands on job strain (Bakker et al. 2005). Job resources can reduce the likelihood that specific organisational aspects will be perceived as sources of stress and may enable individuals to control their emotions and thoughts in response to such job demands (Demerouti and Bakker 2011). For instance, Bakker et al. (2007) found that when Finnish school teachers reported high or positive ratings of supervisor support, organisational climate, and innovativeness (job resources), their perceptions of pupil misbehaviour had less of a harmful association with their work engagement. This suggests that job resources provide teachers with strategies to better manage demanding situations.

The ‘boosting’ effect refers to the way in which job resources become particularly important for employees—or ‘boost’ their engagement—when job demands are high. This notion is consistent with Hobfoll’s (2001) proposition that resources are of greatest use when they are needed most (i.e. during periods of high job demands). This effect was likewise demonstrated in the aforementioned study of Finnish teachers; when pupil misbehaviour was high, the job resources had an even stronger connection with teachers’ engagement (Bakker et al. 2007).

4 JD-R Theory and Links with Resilience

As explained above, JD-R theory has provided important understanding about employee wellbeing. In the current chapter, we propose that it also holds relevance for understanding ‘everyday’ resilience and workplace buoyancy—that is, how individuals overcome low-level adversity at work (e.g., Martin and Marsh 2008). As noted earlier, for this chapter we operationalise resilience in terms of a process involving both resource mobilisation by individuals and resource provision by the context (see Ungar 2008). We suggest that by way of personal and job resources, JD-R theory taps into the idea of resource mobilisation and provision. More precisely, resource provision refers to the job resources that a work context provides employees. Resource mobilisation refers to the personal and job resources that employees utilise in their work. These resources become particularly important in the face of adversity—which can be considered by way of job demands in the JD-R theory. For example, if an employee has a very high workload (a job demand), this can be considered an experience of adversity. The boosting hypothesis in JD-R theory then establishes that in the face of such challenges, resources become particularly important for positive psychological functioning at work. There are clear alignments with resilience here. If employees experience high workload, but do not have access to or are unable to mobilise resources, then their successful adaptation is threatened (e.g., see Howard 2000). In sum, we suggest that JD-R theory has relevance to ‘everyday’ resilience and buoyancy, and that it provides an alternative way of understanding how employees overcome adversity at work. Below, we turn our focus specifically to teachers and how the JD-R theory has been applied to understand teacher wellbeing.

5 Research Employing JD-R Theory in Teaching Populations

The flexibility of JD-R theory and its capacity to integrate both personal and organisational factors into one unified model have made the framework a popular choice for educational researchers. Such work has enabled researchers to glean considerable insights into the nature of the teaching profession and the factors and processes involved in teachers’ wellbeing. This section reviews prior research employing the JD-R theory and identifies key demands, resources, and processes involved in teachers’ occupational functioning. The present chapter also considers a range of methodological approaches to applying the JD-R theory in teaching populations.

-

a.

Key demands and resources. One of the strengths of the JD-R theory is its ability to link key contextual and personal factors to relevant outcomes in a process model. This has enabled identification of salient resources and demands, and how these differentially predict motivation, health, and organisational outcomes. In this section, key studies employing the JD-R theory are described, along with a summary of the key resources and demands that have been shown to influence teachers’ wellbeing. A conceptually and empirically informative test of the JD-R theory in a teaching population was undertaken by Hakanen et al. (2006) among a sample of 2038 Finnish teachers. Drawing on prior research addressing stress and motivation among teachers, the researchers collected data via a paper survey, and examined job demands by way of three indicators (disruptive pupil behaviour, work overload, and a poor physical work environment) and job resources by way of five indicators (job control, access to information, supervisory support, innovative school climate, and social climate). Results of the study provided strong support for the core propositions of the theory: job demands were associated with greater ill-health via burnout, and job resources were related to greater organisational commitment via engagement. Notably, the strength of this study lies in the fact that the results were obtained in half of the sample (using random selection) and cross-validated in the other half, indicating the broad generalisability of the theory. Bakker et al. (2007) extended this research to shed light on the specific interactions between job resources, job demands, and outcomes in a sample of Finnish primary, secondary, and vocational teachers. More precisely, job demands were examined by way of misbehaviour, while job resources were examined in terms of job control (the ability to influence one’s own work), supervisor support, information (pertinent issues are communicated with staff), school climate, innovativeness (the desire to continually improve), and appreciation (colleagues appreciate an individual’s work). Using structural equation modelling, the authors revealed all six job resources and the job demand to be uniquely and positively related to the three dimensions of engagement under examination (absorption: being engrossed in one’s work; dedication: strong involvement, enthusiasm, and pride in work; and vigor: the energy with which work is undertaken). These findings demonstrate that a variety of job resources and job demands are important for teachers, and each of these factors can predict teachers’ outcomes in different ways.

More recently, teachers’ perceptions of autonomy supportive leadership, or the degree to which teachers feel as though their autonomy and self-empowerment are supported by school leaders (Ryan and Deci 2017), has emerged as a particularly relevant job resource. Across samples of Australian and Finnish teachers, structural equation modelling has shown perceived autonomy support to be positively and directly associated with adaptability, engagement, and organisational commitment, and negatively associated with exhaustion and disengagement (Collie and Martin 2017; Collie et al. 2018; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2018). Other applications of JD-R theory have highlighted the importance of social support more broadly for teachers. In a study of 760 Norwegian teachers, Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2018) demonstrated that support from colleagues was a key predictor of teacher wellbeing (measured by the following scales: emotional exhaustion, depressed mood, and psychosomatic responses). Notably, using a diary study which consisted of shortened versions of general engagement, satisfaction, and mental health scales, Simbula (2010) showed that even when existing levels of engagement, job satisfaction, and burnout were accounted for, social support was a unique predictor of these outcomes. Given that social support enables teachers to better deal with uncertainty and unanticipated challenges (Day and Gu 2010), building a positive social climate is thus an important consideration for school leaders.

Other applications of the JD-R have extended the theory by examining the role of personal resources. In a sample of 484 Spanish secondary school teachers, Lorente Prieto et al. (2008) examined personal resources in terms of mental and emotional competencies, which were considered in terms of teachers’ abilities to process large amounts of information and to actively listen to and work with others. They also examined several job demands: quantitative overload (where teachers reported higher workloads than they could manage) and role stress (where individuals receive conflicting demands in their role, or where their role is poorly defined). The authors also examined two job resources: autonomy and support climate. The study found that the personal resources of mental and emotional competencies interacted differently with the engagement and burnout dimensions. Emotional competencies were significant negative predictors of burnout, while both mental and emotional competencies were important predictors of engagement dimensions, providing further evidence of the differential relationships between specific job and personal resources and outcomes.

Another personal resource that has been identified as an important resource for teachers, and especially for beginner teachers is self-efficacy (Dicke et al. 2018). Self-efficacy is defined as the degree to which individuals believe they are capable of succeeding in a specific situation or to attain particular goals (Bandura 1997). Self-efficacy has been examined as a personal resource in studies of Italian, German, and Spanish teachers (Dicke et al. 2018; Simbula et al. 2012; Vera et al. 2012), and has been directly associated with greater work engagement, a decrease in negative perceptions of job demands, and indirectly associated with outcomes such as satisfaction and commitment. In applications of the JD-R theory to Australian teachers, adaptability has been found to predict higher organisational commitment and subjective wellbeing, and lower disengagement (Collie and Martin 2017; Collie et al. 2018), indicating that this personal resource plays a significant role in teachers’ personal and occupational outcomes.

Longitudinal studies have revealed important information about the specific roles of demands and resources over time. Lorente Prieto et al. (2008) were particularly interested in understanding how job demands at the beginning of the academic year predicted job demands and outcomes at the end of the academic year. Structural equation modelling revealed that higher initial levels of overload predicted greater exhaustion and lower dedication (a sense of significance or pride in one’s work) at the end of the year. Moreover, the higher the level of role conflict reported at the beginning of the year, the greater the level of exhaustion reported by teachers at the end of the year. Further still, higher levels of role ambiguity at the beginning of the year were associated with lower levels of dedication at the end of the year.

-

b.

Examinations of the buffering and boosting effects. In addition to the work of Bakker et al. (2007), considerable evidence has been found for the ‘buffering’ and ‘boosting’ effects among teachers. De Carlo et al. (2019), for example, sought to examine how job resources buffered the relationship between demands and strain in a sample of Italian secondary school teachers. Using regression analyses, the researchers found that the job resources of social support and participation in decision-making buffered the negative effect of workload on work–family conflict. Dicke et al. (2018) were similarly interested in the extent to which personal resources could buffer or boost the relationship between strain and demands. Self-efficacy (a personal resource) was found to buffer or reduce the negative association between classroom disturbances and emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, self- efficacy was found to ‘boost’ engagement when disturbances were high. Such findings underscore the important role that demands and resources play not only directly in relation to wellbeing, but also in protecting teachers from experiencing the negative effects of demands, as well as further boosting teachers’ positive experiences at work.

-

c.

Person centred approaches. JD-R theory has likewise been used to inform the development of profiles and clusters that can be used to understand teachers’ experiences and outcomes at work. Prior work in this area has primarily consisted of variable-centred analytic approaches (e.g., structural equation modelling). Although these approaches provide important information about associations among variables, they are focused at a sample-wide level and tend to ignore the existence of subpopulations (Morin et al. 2016). Moreover, they do not consider individual differences on the different variables simultaneously. Considering both variable- and person-centred approaches allows for a broader and simultaneously more nuanced understanding of how JD-R theory can be harnessed to yield important information relating to teachers’ occupational functioning. Importantly, person-centred approaches provide the opportunity to identify profiles of teacher wellbeing. Simbula et al. (2012), for example, assessed several job demands (inequity and role ambiguity) and job resources (professional development and social support) among a sample of Italian secondary school teachers. They identified three behavioural and coping clusters: resourceful (high job demands, high job resources), stressed (high job demands, low job resources), and wealthy teachers (low job demands, high job resources). Resourceful teachers tended to evince higher levels of positive work outcomes (work engagement, organisational citizenship behaviour, and job satisfaction). The authors posited that such teachers were effective as they were able to draw on job resources, particularly during times of high stress. Comparatively, the stressed cluster of teachers tended to demonstrate poorer work outcomes due to the inability to cope with the challenges presented to them. Finally, because the wealthy cluster reported low levels of job demands and high job resources, this cluster found the management of pupil misbehaviour to be less challenging. More recently, Collie et al. (2019) used latent profile analysis to identify four profiles based on JD-R theory, and investigated how these are related to occupational commitment and job satisfaction. The authors considered profile membership in terms of two job demands (barriers to professional learning and student misbehaviour), two job resources (teacher collaboration and input in decision-making), and one personal resource (feeling prepared to teach). Four profiles were identified: the flourisher (low job demands, high job and personal resources), the persister (high job demands, low job resources, high personal resource), the coper (above average job demands, below-average job resources, low personal resource), and the struggler (high job demands, low job and personal resource). Consistent with JD-R theory, the flourisher reported the highest levels of job satisfaction and occupational commitment. The persister and struggler tended to evince the lowest levels of outcomes. The authors further considered school-level profiles, and found that membership in a supportive school profile (largely characterised by high levels of flourishers) was positively associated with greater school-average job satisfaction and occupational commitment.

-

d.

Summary. A growing body of research has revealed salient resources and demands that influence teachers’ work-related wellbeing. Quantitative overload, student misbehaviour, time pressure, role stress, and poor student motivation have been examined in several different countries (Bermejo-Toro et al. 2016; Dicke et al. 2018; Evers et al. 2016; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2018; Tonder and Fourie 2015). Collectively, these demands have been linked to poor wellbeing, such as higher levels of emotional exhaustion, greater stress, increased reports of depressive symptoms, lower organisational commitment, lower engagement, and higher motivation to quit the profession (e.g., Hakanen et al. 2006; Lee 2019; Leung and Lee 2006; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2018). Comparatively, job and personal resources such as social support, supervisory support, value consonance, job control, appreciation, innovativeness, self-efficacy, adaptability, autonomy, organisational climate, and participation in decision-making have been associated with greater subjective wellbeing, higher engagement, superior work–life balance, and greater organisational commitment (Collie et al. 2018; De Carlo et al. 2019; Dicke et al. 2018; Hakanen et al. 2006; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2018). Under specific circumstances these resources and demands can interact in unique ways to influence teachers’ outcomes. Specifically, they can boost and buffer the impact of different resources and demands on teacher wellbeing. Further, it is possible to group individuals in terms of their levels of demands and resources and to establish wellbeing profiles based on this information. Taken together, this research highlights the personal and contextual factors and the processes that facilitate positive psychological functioning for teachers. It further provides important information that may inform the development of interventions targeting teachers’ wellbeing. At the same time, further research is required to extend extant knowledge. For example, further research needs to consider the degree to which different types of job demands relate differentially to the motivational and health impairment process. Similarly, few studies have conceptualised teachers’ wellbeing through a multi-level lens; future studies need to consider how individual demands and resources interact with organisational levels demands and resources. Finally, further longitudinal research is required to better understand causal relationships and the long-term impacts of demands and resources on salient outcomes.

6 JD-R Theory and Resilience Among Teachers

JD-R theory makes an important contribution to advancing conceptualisations of ‘everyday’ resilience and workplace buoyancy among teachers by illuminating the processes underpinning a teacher’s capacity to manage everyday adversity, as well as how these processes relate to wellbeing. Specifically, when teachers are able to access a wealth of resources, both from their environment and within themselves, they may be more capable of managing challenges and adversity in their work, thus enabling them to experience greater wellbeing. For instance, student misbehaviour (a job demand, and an example of a day-to-day challenge commonly faced by teachers; Bakker et al. 2007), may be emotionally and physically taxing; however, teachers who are able to draw on personal resources such as adaptability, and job resources such as social support may be better equipped to manage this experience of adversity. These teachers can adjust their thoughts and behaviours, and draw on guidance and reassurance from colleagues. Successful management of such situations may in turn boost teachers’ sense of self-efficacy and job satisfaction, improving their wellbeing. Thus, as per JD-R theory, teachers who are able to access greater personal and job resources may be better positioned to manage job demands, which in turn may decrease their likelihood of experiencing emotional exhaustion, and enhance their wellbeing at work. By understanding this process, teachers and schools may be able to design interventions and put in place strategies to maximise resource provision and mobilisation, which may strengthen teachers’ capacities to handle their experiences of ‘everyday’ resilience and workplace buoyancy.

7 Implications—Bridging the Gap Between Research and Practice

Having introduced JD-R theory and summarised a range of studies applying the theory among teachers, an important question remains: How can JD-R theory be harnessed to shape interventions targeting teacher wellbeing? The final section of this chapter considers how the propositions espoused in JD-R theory can be translated into strategies to promote teacher wellbeing.

-

e.

Job crafting. Early conceptualisations of the JD-R theory assumed that employees had little control over working conditions, which were considered to be established by employers and organisations (Bakker and Demerouti 2017). However, longitudinal tests of JD-R theory have found that employees often make proactive changes to optimise their workplace experiences (e.g., by actively seeking challenges, mobilising job resources, and finding ways to manage their job demands; Alonso et al. 2019; Tims et al. 2013). This process, referred to as job crafting, is an example of the way in which JD-R theory can be practically applied to enhance teacher wellbeing. Teachers who are highly motivated are more likely to employ job-crafting behaviours. This leads to higher levels of resources and, in turn, boosts motivation (van Wingerden et al. 2017a). This gain spiral not only enhances employees’ job satisfaction, but has also been associated with increased job performance (Leana et al. 2009; van Wingerden et al. 2017b). Thus, in addition to professional learning dedicated to teaching staff about job crafting and how such behaviours can be enacted in the workplace, leaders can support staff by providing opportunities for choice, additional skills training, and mentorship.

-

f.

Other individual efforts. At the individual level, awareness of existing levels of wellbeing and specific triggers and support is important for teachers to understand which interventions may be most effective for them. Bakker and Demerouti (2017) designed the JD- R monitor for this purpose. The JD-R monitor is an online instrument that assesses employees’ various demands, resources, wellbeing, and performance and provides immediate feedback to the employee about these outcomes and how their results compare with others in a similar type of organisation. Teachers may use the JD-R monitor to design their own personalised wellbeing plan or alternatively may choose to discuss the results with their supervisor to develop strategies to manage demands and maximise resources. It is worth noting that thus far, the JD-R monitor has only been used in samples of Dutch professionals (Schaufeli and Dijkstra 2010). Further empirical evidence is thus needed to validate the usefulness of this tool among teachers and in other countries. Another way of promoting self-awareness among employees, which may be effective for teachers is designing a personal demands/resources/tasks chart (van den Heuvel et al. 2015). This chart would require teachers to identify the demands and resources most relevant to them (e.g., writing reports, managing student misbehavior), and to reflect on the types of tasks involved with their job. Reflection on this chart helps employees to identify specific situations that they may craft and how to draw on available resources to achieve this goal. From this chart, a plan is established with specific job-crafting goals, and at the conclusion of each working week, teachers can reflect on their goals, and share this information with other staff or a supervisor as appropriate.

-

g.

School-wide efforts. At a school level, interventions described in prior studies provide promising directions for contemporary interventions involving teachers. Van Wingerden et al. (2013), for instance, designed an intervention to increase special education teachers’ personal and job resources and stimulate job-crafting behaviours. The intervention consisted of targeted exercises and goal-setting activities, and took place over a four week period. At the conclusion of the intervention, participants’ resources, crafting behaviours, work engagement, and job performance were significantly higher compared to pre- intervention scores. To cultivate their resources, participants practised giving and receiving feedback and identifying risk factors and how to manage requests. Such activities may form part of a school-wide intervention program. For example, teachers may focus on giving and receiving feedback on lesson plans, or feedback based on lesson observations. Similarly, teachers may be encouraged to develop their own wellbeing plan, in which they identify the greatest risks to their wellbeing (e.g., student misbehaviour), develop counter-strategies to manage these risks, and consider the types and nature of requests they may encounter (e.g., a parent requesting extra work for a student) and how they can negotiate the nature of such requests to reduce the toll on wellbeing. The job-crafting intervention described by van Wingerden and colleagues (2017a) may also be beneficial as part of a whole-school wellbeing program. This intervention involved participants defining and categorising the types of job tasks they perform: tasks that require considerable time, tasks that had to be performed often, and tasks that had to be performed sometimes. Participants then labelled tasks in terms of urgency and importance, and matched these tasks to their personal strengths, motivations, and potential risk factors. From this analysis, participants considered ways they could draw on their strengths to increase resources and challenge demands and set goals to engage in crafting behaviour around this area.

Summary. JD-R theory provides an overarching framework through which interventions to promote teachers’ wellbeing can be designed. Identification of salient resources and demands, and the implementation of strategies to cultivate resources and reduce demands have yielded promising results in teaching populations across a range of contexts. Although there is considerable evidence to support the implementation of JD-R theory-driven interventions as a means to enhance teachers’ wellbeing, such programs must be implemented with caution. Participating in such interventions may increase teachers’ stress, for example, as such interventions add to teachers’ workloads (Van Wingerden et al. 2013). Additionally, some teachers may be resistant to participating in such interventions, given that they are often organised by the same administrators who may be seen as the source of teachers’ initial high workloads. Thus, interventions need to be specific to teachers’ needs and implemented in a way that allows teachers to see the direct benefits to both themselves and their students. Moreover, it is important to recognise that teachers should not be solely responsible for their wellbeing; instead, schools and educational systems have an important role to play in this process.

8 Limitations

Although JD-R theory provides a promising avenue for future research, a number of limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the model proposed by JD-R theory is an open heuristic and highly flexible (Schaufeli and Taris 2014). Although this is also one of the theory’s strengths, it also necessitates the use of other theories to explain why particular demands and resources relate to particular outcomes. For instance, the effect of job control on organisational commitment may be explained by autonomous motivation, as posited in Self Determination Theory (Fernet et al. 2012). A further limitation of JD-R theory is the nature of job demands and job resources. Not all job demands may be negative in nature, nor are all resources motivational. For example, while demands such as role conflict and ambiguity may be considered hindrances to teachers, problem-solving may be considered a positive challenge (Albrecht et al. 2015). Thus, future research needs to acknowledge this distinction and examine the ways different types of demands may relate to burnout, engagement, and occupational outcomes.

9 Conclusion

Teacher wellbeing is not only an issue of considerable importance for teachers, but also for students, schools, and broader society. This chapter has demonstrated the ways in which organisations and individuals can harness relevant theory to become agents of change in their working context. Job demands-resources (JD-R) theory provides a framework through which teachers and schools can analyse policies and practices, and identify opportunities for growth and sources of potential stress. The flexibility and pragmatism of the JD-R theory, and its applicability for intervention development render it a useful and appropriate tool for both schools and teachers. Moreover, understanding the processes underpinning wellbeing through this framework provides a unique opportunity to empower teachers to gain greater control over their work-related wellbeing.

References

Albrecht, S. L., Bakker, A. B., Gruman, J. A., Macey, W. H., & Saks, A. M. (2015). Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 2(1), 7–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-08-2014-0042.

Alonso, C., Fernández-Salinero, S., & Topa, G. (2019). The impact of both individual and collaborative job crafting on Spanish teachers’ well-being. Education Sciences, 9(2), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020074.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170.

Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy (1. print ed.). New York: Freeman.

Bermejo-Toro, L., Prieto-Ursúa, M., & Hernández, V. (2016). Towards a model of teacher well-being: Personal and job resources involved in teacher burnout and engagement. Educational Psychology, 36(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1005006.

Collie, R. J., & Martin, A. J. (2017). Teachers’ sense of adaptability: Examining links with perceived autonomy support, teachers’ psychological functioning, and students’ numeracy achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 55(Supplement C), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.03.003.

Collie, R. J., Granziera, H., & Martin, A. J. (2018). Teachers’ perceived autonomy support and adaptability: An investigation employing the job demands-resources model as relevant to workplace exhaustion, disengagement, and commitment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 74, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.04.015.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2011). Predicting teacher commitment: The impact of school climate and social–emotional learning. Psychology in the Schools, 48(10), 1034–1048. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20611.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., & Martin, A. J. (2016). Teachers’ psychological functioning in the workplace: Exploring the roles of contextual beliefs, need satisfaction, and personal characteristics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 788–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000088.

Collie, R., & Perry, N. (2019). Cultivating teacher thriving through social–emotional competence and its development. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(4), 699–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00342-2.

Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2010). The new lives of teachers (1st ed.). Milton Park: Taylor & Francis Ltd.

De Carlo, A., Girardi, D., Falco, A., Dal Corso, L., & Di Sipio, A. (2019). When does work interfere with teachers’ private life? An application of the job demands-resources model. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01121.

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499.

Dicke, T., Stebner, F., Linninger, C., Kunter, M., & Leutner, D. (2018). A longitudinal study of teachers’ occupational well-being: Applying the job demands-resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 262–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000070.

Esteves, T., & Lopes, M. P. (2017). Crafting a calling. Journal of Career Development, 44(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845316633789.

Evers, A. T., Heijden, B. I. J. M. van der, Kreijns, K., & Vermeulen, M. (2016). Job demands, job resources, and flexible competence. The mediating role of teachers’ professional development at work. Journal of Career Development, 43(3), 227–243, https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845315597473.

Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senécal, C., & Austin, S. (2012). Predicting intraindividual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(4), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013.

Gu, Q., & Day, C. (2014). Resilient teachers, resilient schools. GB: Routledge.

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001.

Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., & Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 632–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.632.

Howard, J. A. (2000). Social psychology of identities. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 367–393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.367.

Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001.

Leana, C., Appelbaum, E., & Shevchuk, I. (2009). Work process and quality of care in early childhood education. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6), 1169–1192. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2009.47084651.

Lee, Y. H. (2019). Emotional labor, teacher burnout, and turnover intention in high-school physical education teaching. European Physical Education Review, 25(1), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17719559.

Leung, D. Y. P., & Lee, W. W. S. (2006). Predicting intention to quit among chinese teachers: Differential predictability of the components of burnout. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 19(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800600565476.

Lorente Prieto, L., Salanova Soria, M., Martínez Martínez, I., & Schaufeli, W. (2008). Extension of the job demands-resources model in the prediction of burnout and engagement among teachers over time. Psicothema, 20(3), 354–360. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18674427.

Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2008). Workplace and academic buoyancy. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 26(2), 168–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282907313767.

Masten, A. S. (2007). Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Development and Psychopathology, 19(3), 921–930. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407000442.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z.

Morin, A. J. S., Boudrias, J., Marsh, H. W., McInerney, D. M., Dagenais-Desmarais, V., Madore, I., et al. (2016). Complementary variable- and person-centered approaches to the dimensionality of psychometric constructs: Application to psychological wellbeing at work. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(4), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9448-7.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Publications. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/[SITE_ID]/detail.action?docID=4773318.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Dijkstra, P. (2010). Bevlogen aan het werk. Zaltbommel, The Netherlands: Thema.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, A. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. Bauer, & O. Hemming (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health (pp. 43–68). Springer: Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4. Retrieved from http://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:dspace.library.uu.nl:1874%2F304845.

Simbula, S. (2010). Daily fluctuations in teachers’ well-being: A diary study using the job demands-resources model. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 23(5), 563–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615801003728273.

Simbula, S., Panari, C., Guglielmi, D., & Fraccaroli, F. (2012). Teachers’ well-being and effectiveness: The role of the interplay between job demands and job resources. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 729–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.467.

Skaalvik, E., & Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Social Psychology of Education, 21(5), 1251–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9464-8.

Skaalvik, S., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001.

Taris, T. W. (2006). Is there a relationship between burnout and objective performance? A critical review of 16 studies. Work & Stress, 20(4), 316–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370601065893.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032141.

Tonder, D. V., & Fourie, E. (2015). The effect of job demands and a lack of job resources on South African educators’ mental and physical resources. Journal of Social Sciences, 42(1–2), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2015.11893395.

Ungar, M. (2008). Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work, 38(2), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl343.

van den Heuvel, M., Demerouti, E., & Peeters, M. C. W. (2015). The job crafting intervention: Effects on job resources, self-efficacy, and affective well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), 511–532. Retrieved from https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:dare.uva.nl:publications%2F20c7022f-07ec-4c76-88f0-9da0a7420543.

van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2017a). Fostering employee well-being via a job crafting intervention. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.008.

van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2017b). The impact of personal resources and job crafting interventions on work engagement and performance. Human Resource Management, 56(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21758.

van Wingerden, J., Derks, D., Bakker, A. B., & Dorenbosch, L. (2013). Job crafting in schools for special education: A qualitative analysis. Retrieved from https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:tudelft.nl:uuid:92fb8a18-fc71-4fab-aa4c-b7a96c57115c.

Vera, M., Salanova, M., & Lorente, L. (2012). The predicting role of self-efficacy in the job demands-resources model: A longitudinal study. Estudios de Psicología, 33(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1174/021093912800676439.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Granziera, H., Collie, R., Martin, A. (2021). Understanding Teacher Wellbeing Through Job Demands-Resources Theory. In: Mansfield, C.F. (eds) Cultivating Teacher Resilience. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5963-1_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5963-1_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-5962-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-5963-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)