Abstract

Background

Reporting race and ethnicity in clinical trial publications is critical for determining the generalizability and effectiveness of new treatments. This is particularly important for breast cancer, in which Black women have been shown to have between 40 and 100% higher mortality rate yet are underrepresented in trials. Our objective was to describe changes over time in the reporting of race/ethnicity in breast trial publications.

Patients and Methods

We searched ClinicalTrials.gov to identify the primary publication linked to trials with results posted from May 2010–2022. Statistical analysis included summed frequencies and a linear regression model of the proportion of articles reporting race/ethnicity and the proportion of non-White enrollees over time.

Results

A proportion of 72 of the 98 (73.4%) studies that met inclusion criteria reported race/ethnicity. In a linear regression model of the proportion of studies reporting race/ethnicity as a function of time, there was no statistically significant change, although we detected a signal toward a decreasing trend (coefficient for quarter = −2.2, p = 0.2). Among all studies reporting race and ethnicity over the study period, the overall percentage of non-White enrollees during the study period was 21.9%, [standard error (s.e.) 1.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 18.4, 25.5] with a signal towards a decreasing trend in Non-White enrollment [coefficient for year–quarter = −0.8 (p = 0.2)].

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate that both race reporting and overall representation of minority groups in breast cancer clinical trials did not improve over the last 12 years and may have, in fact, decreased. Increased reporting of race and ethnicity data forces the medical community to confront disparities in access to clinical trials. This may improve efforts to recruit and retain members of minority groups in clinical trials, and over time, reduce racial disparities in oncologic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

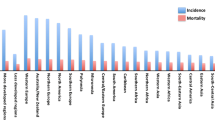

SEER Explorer Application. Cancer.gov. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html?site=55&data_type=1&graph_type=2&compareBy=race&chk_race_9=9&chk_race_8=8&rate_type=2&sex=3&age_range=1&stage=101&advopt_precision=1&advopt_show_ci=on&advopt_display=2

Cancer Disparities in the Black Community. American Cancer Society. Accessed April 18, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/about-us/what-we-do/health-equity/cancer-disparities-in-the-black-community.html

Baquet CR, Mishra SI, Commiskey P, Ellison GL, DeShields M. Breast cancer epidemiology in blacks and whites: disparities in incidence, mortality, survival rates and histology. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(5):480–8.

DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding Sauer A, Kramer JL, Smith RA, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2015: convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):31–42. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21320.

Kohler BA, Sherman RL, Howlader N, et al. Annual report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2011, featuring incidence of breast cancer subtypes by race/ethnicity, poverty, and state. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv048.

The Role of Safety-Net Hospitals in Reducing Disparities in Breast Cancer Care | SpringerLink. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://link.springer.com/article/https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-11576-3

Fayanju OM, Edmonds CE, Reyes SA, et al. The landmark series—addressing disparities in breast cancer screening: new recommendations for black women. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-12535-8.

Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Miller KD, et al. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(6):457–80. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21314.

Hispanic or Latino People and Cancer | CDC. Published January 25, 2023. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/health-equity/groups/hispanic-latino.htm

Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, et al. Event-free Survival with pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):556–67. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2112651.

Siegel SD, Brooks MM, Lynch SM, Sims-Mourtada J, Schug ZT, Curriero FC. Racial disparities in triple negative breast cancer: toward a causal architecture approach. Breast Cancer Res. 2022;24(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-022-01533-z.

NIH Policy and Guidelines on The Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research. NIH: Grants & Funding. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities/guidelines.htm#:~:text=It%20is%20the%20policy%20of,that%20inclusion%20is%20inappropriate%20with

NIH Policy on the Dissemination of NIH-Funded Clinical Trial Information. Federal Register. Published September 21, 2016. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/21/2016-22379/nih-policy-on-the-dissemination-of-nih-funded-clinical-trial-information

Clinical Trials Registration and Results Information Submission. Federal Register. Published September 21, 2016. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/21/2016-22129/clinical-trials-registration-and-results-information-submission

NOT-OD-18-014: Revision: NIH Policy and Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research. NIH: Grants & Funding. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-18-014.html

Race and National Origin. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Published August 11, 2022. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.nih.gov/nih-style-guide/race-national-origin

U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221

Fain KM, Nelson JT, Tse T, Williams RJ. Race and ethnicity reporting for clinical trials in ClinicalTrials.gov and publications. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;101:106237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2020.106237

Potential Regional Differences for the Tolerability Profiles of Fluoropyrimidines - Rutgers University. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/esploro/outputs/journalArticle/Potential-Regional-Differences-for-the-Tolerability/991031665631004646

Masuda N, Lee S, Ohtani S. Adjuvant capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. New Eng J Med. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1612645

A randomized phase III post-operative trial of platinum-based chemotherapy (P) versus capecitabine (C) in patients (pts) with residual triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC): ECOG-ACRIN EA1131. J Clin Oncol. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.605

Cahan EM, Hernandez-Boussard T, Thadaney-Israni S, Rubin DL. Putting the data before the algorithm in big data addressing personalized healthcare. NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2:78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0157-2.

Chen MS, Lara PN, Dang JHT, Paterniti DA, Kelly K. Twenty years post-NIH Revitalization Act: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual: renewing the case for enhancing minority participation in cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2014;120(Suppl 7):1091–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28575.

Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. New Eng J Med. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1910549

KEYNOTE-522 - High-Risk Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) | HCP. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.keytrudahcp.com/efficacy/early-stage-triple-negative-breast-cancer/

Collier Jackson FL. Evolutionary and political economic influences on biological diversity in african americans. J Black Stud. 1993;23(4):539–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193479302300407.

Protocol Search. Accessed April 16, 2023. https://www.nrgoncology.org/Clinical-Trials/Protocol-Search

Simon MS, Du W, Flaherty L, et al. Factors associated with breast cancer clinical trials participation and enrollment at a large academic medical center. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2046–52. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.03.005.

Ashing K, Rosales M, Fernandez A. Exploring the influence of demographic and medical characteristics of African-American and Latinas on enrollment in a behavioral intervention study for breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(2):445–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0758-9.

Germino BB, Mishel MH, Alexander GR, et al. Engaging African American breast cancer survivors in an intervention trial: culture, responsiveness and community. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(1):82–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0150-x.

Robinson BN, Newman AF, Tefera E, et al. Video intervention increases participation of black breast cancer patients in therapeutic trials. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2017;3(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-017-0039-1.

Sturgeon KM, Hackley R, Fornash A, et al. Strategic recruitment of an ethnically diverse cohort of overweight survivors of breast cancer with lymphedema. Cancer. 2018;124(1):95–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30935.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Keegan, G., Crown, A., DiMaggio, C. et al. Insufficient Reporting of Race and Ethnicity in Breast Cancer Clinical Trials. Ann Surg Oncol 30, 7008–7014 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-14201-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-14201-z